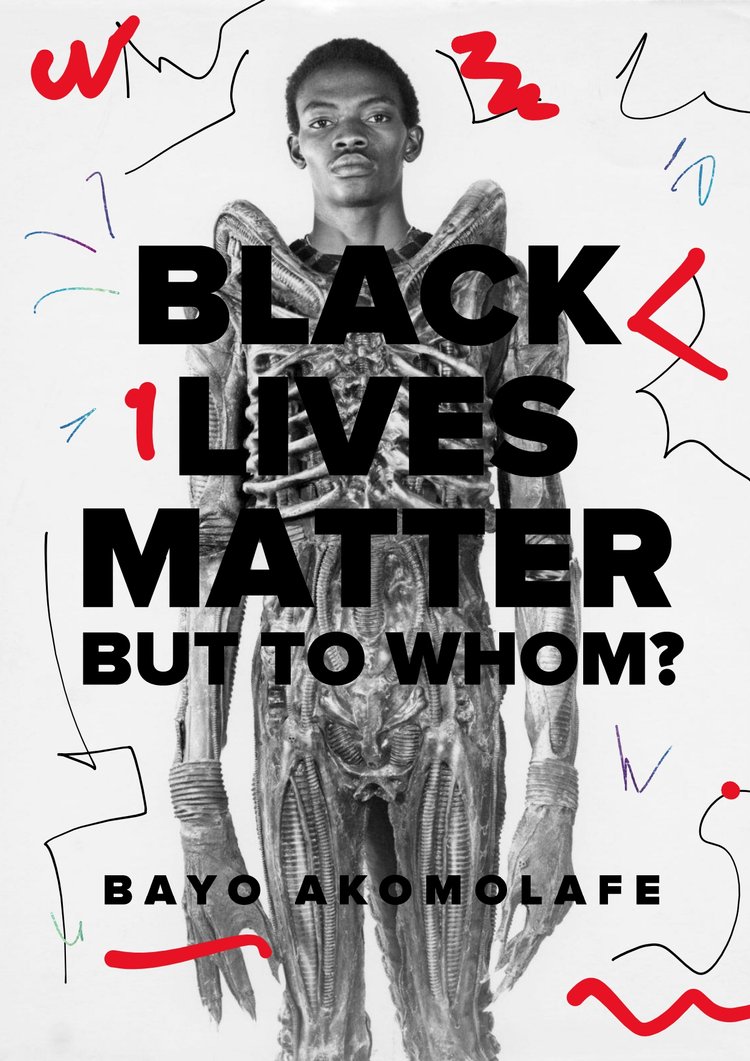

UC Berkeley fellow Bayo Akomolafe discusses how seeking justice and acknowledgement can reinforce racist structures of power. (Illustration courtesy of Bayo Akomolafe)

Juneteenth, made a federal holiday in 2021, is seen by many as a moment to celebrate Black emancipation and freedom. A day to acknowledge America’s history of violent, racist oppression.

But that recognition can come at a cost, said Bayo Akomolafe, a global senior fellow with UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute. He argues in a recent essay that the recognition — and celebration — of the holiday might let America, and its continuing racist structures, off the hook.

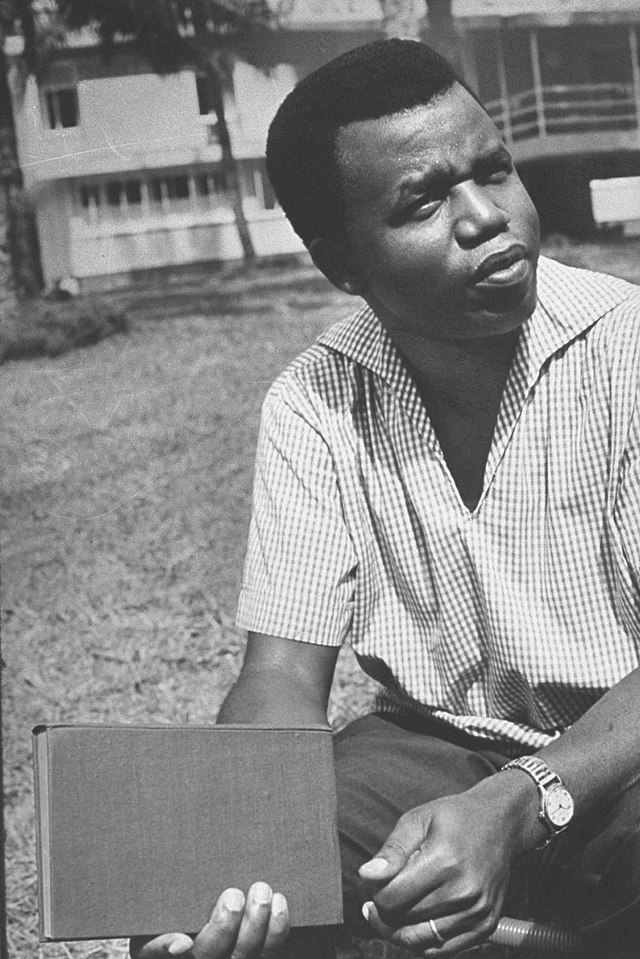

(Photo courtesy of Bayo Akomolafe)

“(Juneteenth) is an acknowledgment,” he said. “But victory or justice found in that recognition is sometimes a form of white closure that allows people to move on from it without recognizing what is still occurring.”

Born in western Nigeria, Akomolafe, an award-winning author, has created community spaces at Berkeley to explore pressing societal problems, most recently hosting a discussion about the climate crisis that centered Black and Indigenous perspectives. He also says his West African Yoruba ancestry gives him a critical, independent way to understand American racism through the lens of the African diaspora.

Berkeley News spoke with Akomolafe about the significance of Juneteenth, and how seeking “a politics of recognition” can reinforce racist structures of power that continue to cause division.

[This interview was edited for length]

Berkeley News: How important is it to recognize Juneteenth?

Bayo Akomolafe: In terms of a politics of recognition, for Black people, there is this longing and wanting to be appreciated, wanting to be seen. Deservedly so. It’s a desperation and anxiety to be taken from the pain, suffering and oppression of the past. To commemorate the marks on Black bodies, the stories of a yearning for emancipation. This freedom is worth investigating, worth celebrating.

And it is. We need this.

If I were living in the U.S., I probably would want that acknowledgement through Juneteenth. But I am not, so I have a slightly off-center perspective that removes me from that circumstance, thus allowing me to offer a potentially generative perspective. And it is this: I feel it is often the case that when recognition is granted, something else gives way. Something is lost.

Juneteenth is not just a celebration, it’s a quest for visibility. I often ponder that, if we submit ourselves to the surveillance of the state to be seen and appreciated, if we render ourselves visible and intelligible to the grammar of capture, how are we reinforcing the architecture of sensorial incarceration? How do we inadvertently postpone the exquisite, even in the celebration and centering of freedom? What is freedom indebted to?

Are there historical events you’ve observed that bring about those questions for you?

I think about how Christianity became a world territorializing force through Constantine in Rome. At first, in the shadows of empire, it was a nebulous subterranean force; it stole into environments, becoming this fugitive and condemned thing. And then, all of a sudden, it was garlanded with purple robes, a crown, and a scepter. The calendar was changed to recognize Christianity, and then the very structure of power that once burned Christian bodies became a Christian empire.

You play the game, but once you win the game — you become the game.

I feel it is often the case that when recognition is granted, something else gives way. Something is lost.”

I take the point of noticing that even activism and justice creates a form of violent closure. I want to be able to arrive at justice and say, “yes, this is now justice.” But it’s still part of the framework of intelligibility that makes capture and slavery a reasonable thing. That makes incarceration an intelligible act.

So, I’m wondering about Juneteenth and what it does. What it is doing. It’s an acknowledgment, but victory or justice found in that recognition is sometimes a form of white closure that allows people to move on from it without recognizing what is still occurring.

I think for post-humanist scholarship that wants to do more, it’s necessary to have this conversation.

How do you start this conversation and what should it address?

I think this is a cross-Atlantic conversation between the blackness of diaspora, and the blackness of the homeland, and it needs to happen. It’s not just about finding unity in things like ‘’Wakanda” as a Black point in the conversation.

Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe’s novel, “Things Fall Apart,” is the most widely studied and translated African novel. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

It’s a conversation between Chinua Achebe and James Baldwin, between (Kwame) Nkrumah and Martin Luther King Jr. It’s a very alive and urgent ancient conversation that asks: What is Black history in spite of its culture? And what do we do with blackness in the midst of continued violence?

Justice isn’t producing the world that we hoped it would, and activism is kind of allegorically engineered to reproduce the same realities we’re in. What we see as recognition or justice does not nullify the problem. It keeps it alive in a strange way.

So, there is a sense in which an acknowledgment of terrible and painful acts can reinforce oppressive presence and activate pathways that reinforce the violence and divisiveness of statehood.

Can you give an example of how that is happening now?

To use the parlance of American politics, you can have entirely well-intentioned, left-wing politicians who know what to say, how to say it and when to say it. And the very structures that keep Black people under those oppressive circumstances are preserved and strengthened because those politicians are still operating within that structure.

In Florida, Ron DeSantis is heading back to the state of banning books. There is a clampdown on literature and the telling of stories that include Black people, stories described by a disparaging term, at least in the mouths of the right-wing in America, called “wokeness.” On the other hand, there is an insistence that everyone has to know Black stories, and must be condemned if they do not.

To see both sides is such a charged minefield in American political discourse today, but there is a sense — without reducing this to some kind of mathematical equivalence — that while both sides are insisting to be heard, they are preserving the same dynamics: A structure that oppresses and divides.

Even the seeking of reparations from slavery is still submitting ourselves to this baseline reality that is entangled within the violence we’re trying to upset. Would reparations change the reasoning behind slavery? Would it bring false closure to racism that still exists in America?

How do we change this structure that oppresses and divides?

What one needs often is a break from that economy of reason altogether. To break away from this material reality where Black people struggle to be recognized, and into a different politics that builds and unites, even in hostile dis-recognition — like the slaves did.

And there is an impulse to activism that leaves this change for us to create.

Justice isn’t producing the world that we hoped it would.”

But I don’t know if this is immediately amenable to everyday practices. We still have to eat, fetch water to drink, cook food, and pay the bills. It’s not to say, “do these seven things every day with a collective of people and we’re in the clear.”

There’s no speeding up here.

There’s no getting to the other side. There is no “I have to do this” or “I have done this.” There’s only the doing. It’s how things breathe. It’s how the world becomes.

But how can we change the world if we don’t actively change it?

The idea to “change the world” is a typical European concept. The world is constantly moving and it’s not singular. You cannot reduce it to a single entity. You don’t need the neurotypical idea of monumental change to notice that transformation is happening all the time.

We can frame a politics that admits that we are not the agents of change we pretend to be, or think we are. Whale or shark feces might be just as important, or maybe even more important, than all the protesting, all the writing, and all the books that you and I can produce.

We can also take a step back from wanting acknowledgement to see the big picture. To see the reality that we continue to operate within, and ask ourselves: How did we lose our way? And then, How do we lose our way together?

“There’s no speeding up here,” said Akomolafe. “… There is no ‘I have to do this’ or ‘I have done this.’ There’s only the doing. It’s how things breathe. It’s how the world becomes. (Illustration courtesy of Bayo Akomolafe)

We have to sit in the reality that we are in, because despite the recognitions we seek, whether they be Juneteenth or otherwise, there are no reality break rooms to find closure in. We have to live within the mess together, and understand we’re not always going to find the answers.

But we must do that together.