Juana Maria Rodríguez: Sex work is a queer issue

UC Berkeley professor discusses her new book Puta Life and how the history of sex work is intertwined with the queer community’s most pressing issues

June 27, 2023

UC Berkeley Ethnic Studies Professor Juana Maria Rodríguez discusses her new book Puta Life and how the history of sex work is intertwined with the queer community’s most pressing issues. (Illustration by Joie King)

Sex work is considered one of the oldest professions in history. But in contemporary American culture, it is still a taboo topic. And due to the criminalization and stigma that surrounds the industry, the lives and stories of sex workers often get lost and devalued.

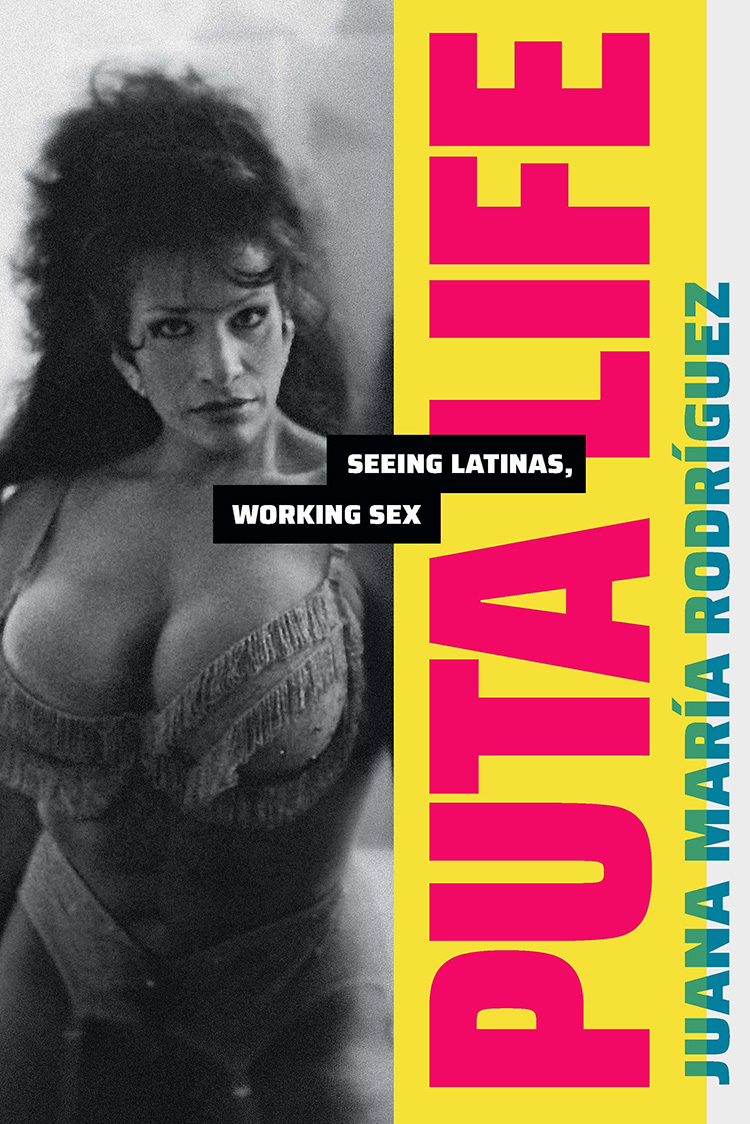

Juana Maria Rodríguez, a UC Berkeley ethnic studies professor, attempts to uncover those stories in her new book Puta Life: Seeing Latinas, Working Sex. Through an examination of archival photographs, illustrated biographies and visual accounts, Rodríguez relates intimate stories of Latinx sex workers from around the world and demonstrates the ways they have always “formed part of queer worlds.”

Rodríguez said she wanted to present the “fullness of sex worker lives,” in part, to inspire the queer community to reflect on the sexual regulations that continue to impact sex workers, and the history and political stigmatization they both share with each other.

“All of us have the right to lead dignified lives,” she said. “Sex workers have always been part of queer communities, and the issues they face — sexual regulation, stigmatization and hate-fueled violence — are core to the LGBTQ community.”

Rodríguez, who recently received the Kessler Award from the Center for Gay and Lesbian Studies for her lifelong contributions to the field of LGBTQ studies, spoke with Berkeley News about the historical links between the queer community and sex work, and how anti-LGBTQ rhetoric and policies in the U.S. impact these communities in violent ways.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Berkeley News: In your book, you feature Latinx sex workers who come from various backgrounds, including Adela Vázquez, an iconic 1990s San Francisco transgender activist. Through your research, did you find other links between the histories of sex work and the queer community?

Adela Vázquez, a Cuban American transgender activist and performer, was also an organizer in the 1990s with an HIV prevention organization. (Photo courtesy of Juana Maria Rodríguez/Puta Life)

Juana Maria Rodríguez: Sex workers have always been part of queer history, and queers have always been part of sex worker movements. In my research, I found lesbian sex workers organizing against police violence in Cuba dating back to 1888. And of course, some of our most famous queer icons, like Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, were also sex workers. In fact, those legendary activists together started a sex worker organization in the 1970s called the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR).

While some sex workers choose this profession, others really feel like they have no choice. At the time when STAR was created, a lot of young, queer people were getting kicked out of their houses, and many of them turned to sex work for survival. Without employment protections, trans women faced harsh economic discrimination, and sex work became one of the few jobs that they could have, exposing them to constant police harassment and arrest.

People are more than their profession, and all of us have the right to lead dignified lives. This month, HBO is showcasing a film, “The Stroll,” that highlights these connections about transgender sex workers.

And so, in this book, I really wanted to address the ways in which sex work is regulated and how criminalization makes everything bad about sex work worse.

Sylvia Rivera at a STAR rally in 1970. Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson were sex workers who started the sex worker organization in New York. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia)

Statistics do show that sex workers are 200 times more likely to be murdered. How is that related to sex work criminalization?

Sex work is so many different things. It’s pornography, which is this billion-dollar industry, and it’s also the kind of survival sex work that people might do on the street. But it’s also things like OnlyFans, which doesn’t have any person-to-person contact. And yet, all of these things are stigmatized, and often criminalized, just because they bring together sex and money.

And because it is illegal, it is harder for sex workers who are victims of violence, rape and trafficking to report those crimes. They also are not valued by law enforcement as victims in the same way other murder victims are. So sexual predators find them as easy prey.

Criminalization also gives police officers the right to stop you if they suspect you are engaged in sex work. So we can begin to see how laws against sex workers expose all kinds of marginalized populations to state surveillance.

Who’s more likely to get stopped? It’s “stop and frisk” for trans folks.

It’s also interesting that, in 2023 in many states, gay marriage is legal — but two consenting adults can’t negotiate a sexual exchange for money. That’s still illegal.

Vanessa del Rio, the first non-white pornography star, wearing a stereotypical Latina spitfire outfit from the 1981 film The Dancers. (Photo courtesy of Juana Maria Rodríguez/Puta Life)

But how are those policies related?

Sex work is one of these areas that really brings together a lot of different issues that have to do with bodily autonomy. And those issues have really been core to the LGBTQ movements.

That we have the right to determine our own relationships: how we love, how we work and what we do with the resources that we have, including the labor of our own bodies. Also, queer people have always thought differently about sex and relationships.

Straight people get handed a script that says, “This is what love and marriage and family looks like. You date, you get married, and maybe you even save sex until then.” You pick that one person, and they’re there forever, right? But queer people, we don’t get the script, so we’ve experimented to figure things out for ourselves. We get to have a lot more different kinds of relationships or perhaps choose to live outside of coupledom altogether.

Historically, we have made up our own rules.

As figures associated with urban geographies, sex workers appear in the camera rolls of almost every famous photographer. (Photo by Henri Cartier Bresson)

So I think queer people are more open about having casual sex, hook-up sex, and sometimes that becomes transactional sex, in which sex is seen as a service that can be purchased.

How is it a service?

I pay for a massage. I pay for a therapist every week. So paying for sex, for a lot of us, could be seen in the same way. Any sex worker will tell you that a certain percentage of their clients are disabled. Maybe they are anxious or insecure, maybe they have a hard time going to clubs, dating or finding a sexual partner on the internet.

Some people really need sexual touch, and some people pay for it just like you might pay for other kinds of intimate care. We have to get rid of this idea that sex workers are only trafficked 19-year-old girls having sex with 60-year-old men.

That is the scenario we always seem to default to when we imagine sexual labor.

Why do you think that is the default perception of what sex work is, and who sex workers are?

These are complicated stories. Just like everybody else, sex workers are more than their profession.”

In public discourse, sex workers historically have been placed in this false binary that says, “Whatever deviates from straight, white-normative sex is wrong.” And we have seen that culture permeate into the perceptions and policies that impact sex workers and the queer community.

It really isn’t an exaggeration to make comparisons between the anti-gay and anti-trans policy happening in Florida right now with what happened in Germany during the rise of fascism before World War II. There was a thriving queer and transgender community in Germany, and they targeted those populations through a “moral crusade” of extreme nationalism that linked sexual purity and racial purity. They limited what people could read and tried to control how people think, dress and act.

Has American culture been any better, in comparison?

Well, there was also a time in the United States when you could be arrested for cross-dressing. You had to have at least three items of gender appropriate clothing. A woman could be arrested for wearing pants.

These new laws against drag shows, and that allow the state to search our bodies out of fear we use the wrong bathroom, are taking us back to that. It’s a message that it’s OK to hate. They are trying to erase queer parents and queer kids and kids that have queer neighbors and queer teachers and queer teens and grandparents. American politicians are using language that describes trans people as being sexual predators, when everything we know is quite the opposite.

“They are trying to erase queer parents and queer kids and kids that have queer neighbors and queer teachers and queer teens and grandparents,” said Rodríguez. (Photo by Bénédicte Desrus)

The way the public views sex workers, I think, is often conflated with this anti-queer sentiment.

Something that shocks me is that, in the United States, capitalism is king and so is to be an entrepreneur. And nobody is more entrepreneurial than sex workers. But this idea of individual and financial freedom somehow comes apart when it comes to sex work. I think the problem is that they haven’t found a way to control it enough to extract a profit from it.

So in this book project, I was really thinking about how the history of sex work has always been entangled with the history of queer rights. And the idea that these moral crusades against LGBT people have lingering effects that impact sex workers in violent ways.

How important is it to understand this history during Pride month?

In this book, I really wanted to get queer people to think about the ongoing sexual regulations that continue to impact the sex worker population. Sex work continues to be the most dangerous job in the country, perhaps in the world.

A still from the film Plaza de la Soledad by director Maya Goded. “These are complicated stories,” said Rodríguez. “Just like everybody else, sex workers are more than their profession.” (Photo courtesy of Juana Maria Rodríguez/Puta Life)

If we care about the murder of transgender people, we need to understand that some of them, not all of them, were involved in sex work when they were murdered. And we shouldn’t care less about them, we should care more about the violence that impacts all sex workers.

Just like a lot of people didn’t think they knew gay people before gay people started coming out, a lot of people don’t think they know a sex worker, but they are that mom that’s picking up their kid at the daycare, or he’s the student in your class. Or maybe it’s your older aunt who lived by herself and traveled the world.

These are complicated stories. Just like everybody else, sex workers are more than their profession. So I really wanted to present the fullness of sex worker lives and hopefully inspire others to work against the ongoing criminalization and stigmatization that defines their lives.