Student-entrepreneur Alishba Imran: You don’t have to wait to change the world

The computer science and engineering major shares her journey as a young pioneer in robotics and machine learning: "Age is just a number."

Brandon Mejia/UC Berkeley

September 5, 2023

This I’m a Berkeleyan was written as a first-person narrative from an interview with second-year student Alishba Imran. This story is also part of the Berkeley Changemaker series, which highlights innovative members of the campus community engaged in work and research that tackles society’s most pressing issues.

When it comes to solving problems and making a difference, I don’t think it matters how old you are.

Age is just a number.

When I was 14, I launched an app that uses blockchain to improve supply chain transparency with the goal of putting an end to counterfeit medication in developing countries. Part of this project was integrated into IBM’s healthcare supply chain tracking systems.

Courtesy of Alishba Imran

At 17, I founded my first company, Voltx, and this past summer, I worked with Tesla on research that can speed up the time it takes to manufacture battery cells using machine learning and physics models.

I’m currently co-authoring a textbook for O’Reilly Media, Machine Learning for Robotics, to make more accessible the processes of using deep language learning models to build robotics that can change the way we live.

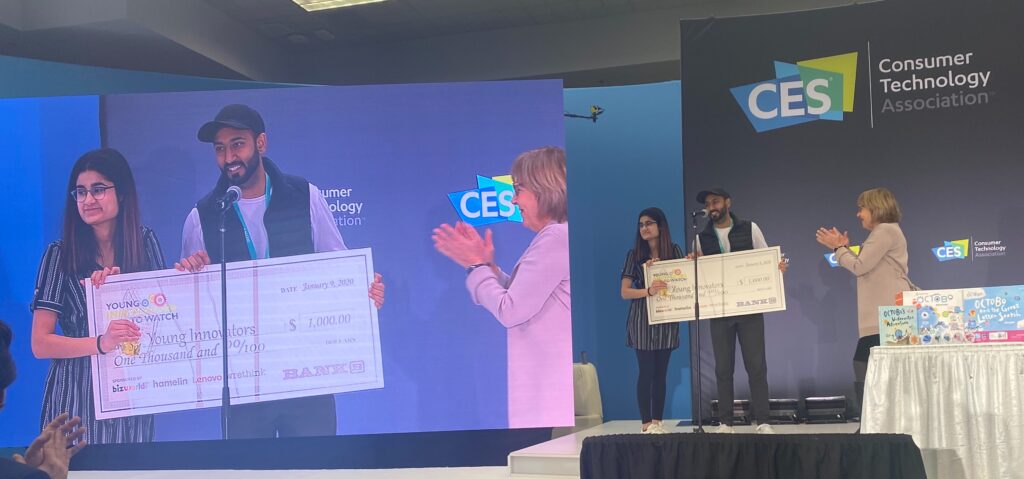

I’ve had the opportunity to speak at some of the largest tech conferences in the world — sometimes to over 40,000 people — about my research projects and companies. And at the age of 18, I was named in Teen Vogue’s 21 under 21 and also one of the Top 100 Most Powerful Women in Canada.

As a 19-year-old computer science and engineering student at UC Berkeley, I think what matters most is your ability to obtain and share knowledge as an active and engaged learner. And to use your skills to solve real problems — and make a difference — in something you are passionate about.

There are a lot of people in the tech industry trying to build the next big social media or note-taking app that will attract millions of dollars from big investors and bolster their company’s value.

But I don’t think the end goal of any company should be based on its monetary value, but rather the value it brings to society.

There are many urgent problems that need to be addressed in the world. The greatest challenges of our time — climate change, health care reform and finding ways to create sustainable energy sources.

As young students and innovators, I think we have to continually ask ourselves: How do we put our talents and passions toward working on these hard problems?

Finding the answer to that question, personally, has been a great motivation for me to dive deeper into my interests. And that has been a journey that has taken me around the world.

My family is originally from Pakistan and we immigrated to Canada when I was 5 for better educational options. I grew up and went to school in Toronto, Ontario, where I’ve lived for most of my life.

As a child, I was always very curious and asked a lot of questions about how things work. From appliances around the house to vehicles and computers. At a young age, I found engineering and computer science very interesting because of how it technically challenged me and the vast applications to solve tangible problems.

In middle school, I learned how to code and was one of the first girls to join the robotics team. That was really my first glimpse into learning about building something real. I was really excited because I would travel to global competitions to meet other people from different countries who were just as interested in technology and engineering as me.

Courtesy of Alishba Imran

Through that experience, I knew that I wanted to create deep technology that is not easy to build, but also extremely useful in solving challenging problems.

As a teenager, I was fortunate to have exposure to nonprofit service work where I would visit rural villages in Pakistan and India to talk to people about the problems they faced. A major issue families talked about was the proliferation of counterfeit medication.

Using the wrong medicine could be detrimental to anyone’s health. Most people don’t even know this is a big problem — over one million people die because of this every year. And counterfeiters basically make a lot of money at the expense of human lives.

I remember meeting with a mother who described how her son had consumed medication that made him so sick he was in the hospital for weeks. Hearing a real person talk about how it impacted them motivated me to find a way to help.

Counterfeit medication is an issue because there’s no transparency or tracking of where they are coming from before they end up on shelves. I realized that blockchain could be a great application to build a platform and database to record and trace medication transactions, to create cleaner supply chains.

I created a supply chain-tracking app, HonestBlocks, to help catch counterfeit medications in developing countries. I reached out to pharmacies that might be interested in piloting my technology, and I connected with companies and emailed researchers at places like IBM — they do a lot of work in supply chain tracking and transparency — to get their advice.

Courtesy of Alishba Imran

Engineers from IBM contacted me and wanted to work with me. And they eventually integrated some of the code from my app into their systems that track medication supply chains to this day.

It felt amazing that I could write a piece of code to build a real product that impacts people in such a positive way. It really motivated me to develop more skills that I could use to help in other ways.

From here, I dove deep into machine learning (ML) — a branch of AI that uses data and algorithms to mimic the way humans learn. It appealed to me because there are just so many interesting ML applications that can solve real problems in the hard sciences.

In high school, I spent a lot of time teaching myself ML concepts and techniques. After school, I would read textbooks and papers online and meet with researchers in the field.

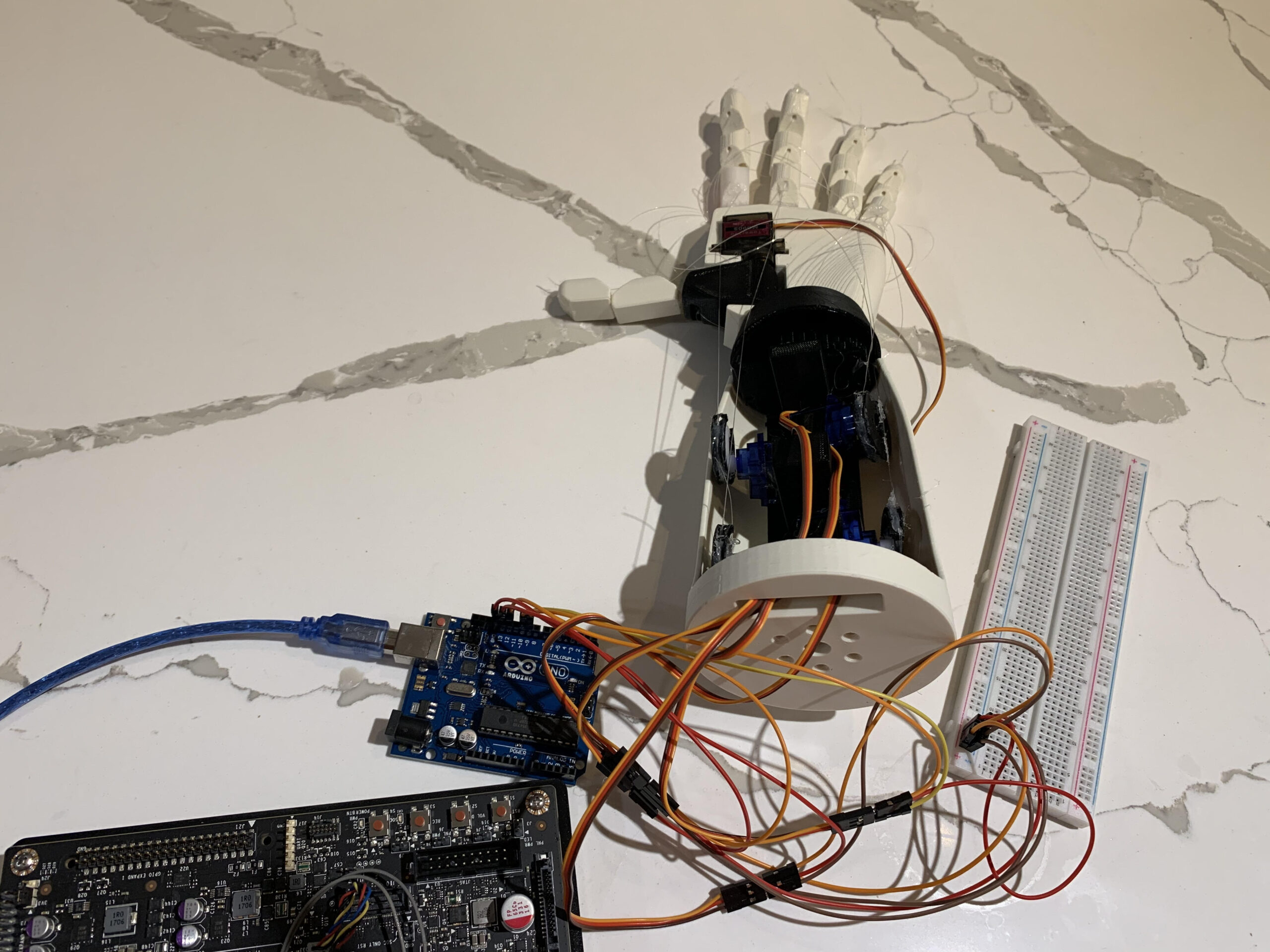

I tried to find applications for the ML knowledge I had just learned, and personally, I knew family and friends, including an aunt of mine, who were amputees. That led me to work on a project with prosthetics in collaboration with San Jose State University and the BLINC Lab.

We developed new 3D modular printed material to bring down the cost of prosthetic arms from $10,000 to $700. I also created a machine learning algorithm that improved the grasping capabilities for users of prosthetic arms, to make it easier for amputees to do daily tasks.

After I published my work and research from this project, the founder of Hanson Robotics, the company that created Sophia the robot, reached out to me to work on machine learning projects focused on neuro-symbolic AI. I got to lead various research projects and focused on developing an open-source lower cost hardware platform for Sophia.

Courtesy of Alishba Imran

That experience helped me to understand the importance that time and cost have in creating changemaking products and innovations. The faster it is to build something, the cheaper it costs, and the cheaper something is, the more people can use it.

As a student, climate change was always an issue that interested me. After school, my friends and I would research the different types of problems the world faces when it comes to global warming and our overconsumption of fossil fuels.

In my senior year of high school, I started to think of ideas to use machine learning to help with climate change. I worked on different ideas throughout the pandemic and realized the way to make an impact is by maximizing energy storage.

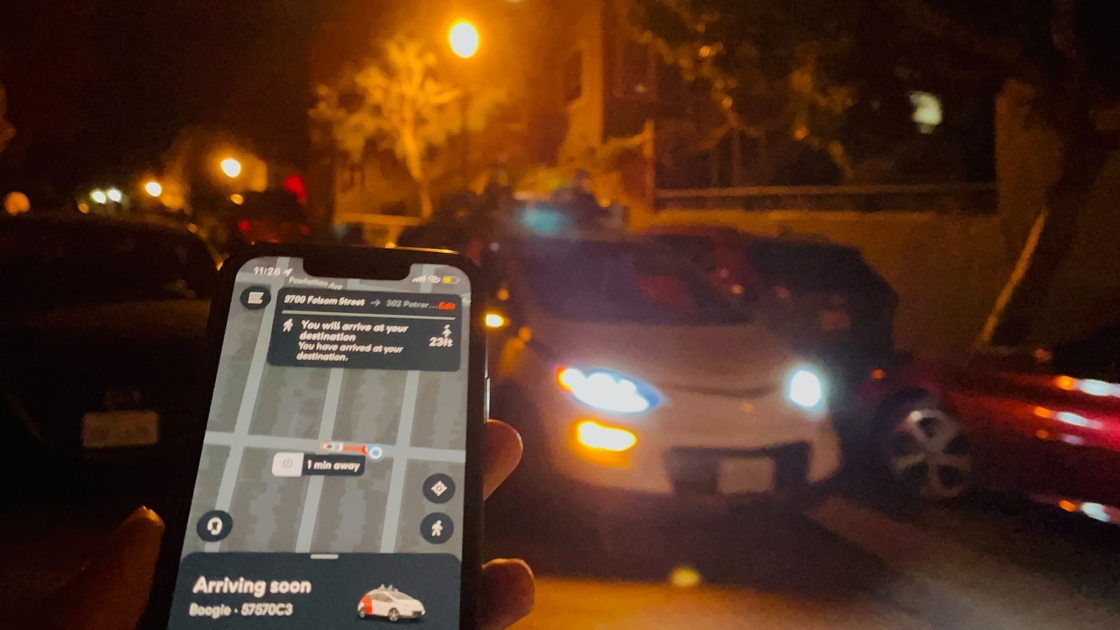

Renewable energy sources like solar or wind cost much less than nonrenewable sources. But the reason we aren’t using solar as much is because there’s not enough energy storage capacity for it. After I graduated high school in spring 2021, I launched Voltx, a startup that was funded through the Delta Fellowship.

I moved to San Francisco to work full-time with my co-founder to find ways to scale the storage of batteries for solar panels and other applications, like electric vehicles (EV).

Courtesy of Alishba Imran

Initially, we broke down the entire value chain for batteries, all the way from raw materials to the end application of these devices. One common thing that we saw within a lot of electrochemical devices — like supercapacitors or batteries — is just how long it takes to develop them.

It can take anywhere from three months to a whole year to develop a battery. And the reason for that is because testing for these battery cells is very manual.

So we began to build this predictive model — through the use of manufacturer’s data and our own algorithms — that can reduce battery testing time down from three months to a few days. Through that testing, the data that we get can then be used to forecast and predict the life of the battery cell using machine learning and physics models.

Courtesy of Alishba Imran

If applied correctly, companies could build more solar batteries, or batteries for EVs, in less time.

We worked with a few of the largest manufacturing companies in the batteries and supercapacitor space. We ran pilots of over $60,000 and booked revenue of a couple thousand with manufacturers to test their products and reduce their testing time by over 80%.

And I also raised a pre-seed round of over $1 million for Voltx through venture capital investors. I am still continuing to build on this technology and research as a second-year student at Berkeley.

Being at Berkeley and in the Bay Area, it’s nice to be in an environment where I’m continually meeting dedicated students and professors that are working on hard problems that need to be solved. I had the chance to collaborate on a project with Google and Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences Professor Ken Goldberg’s group using large language models to help robots do tasks.

The campus also has a ton of STEM resources for students to seek out. Something fun I have been doing is joining and organizing weekend code-builder sessions. Students participate in a mini-hackathon where you work on a project that you’re interested in. It has been a really great way to meet other students that are interested in similar things.

Brandon Mejia/UC Berkeley

On campus this year, I’ve decided to spend more time learning about the fields I’m interested in. Alongside my projects, this involves doing research with professors to learn best practices and build out my technical skills. I am currently conducting research in large language model and reinforcement learning research at Berkeley AI Research Lab (BAIR).

When I reflect on problems that I really want to spend time focusing on, I ask myself: What is the problem that I want to dedicate the next 10 years of my life to? And I definitely think using my skills in machine learning, computational methods and robotics to solve problems in sustainability, and accelerating scientific discovery, is really what I want to be doing.

Brandon Mejia/UC Berkeley

Berkeley is helping me to accelerate progress in those skills even more. Whether it be discovering novel electrodes for higher energy density batteries or using new materials that can be used in solar panels or photovoltaic cells.

There’s a lot of interesting stuff happening here with automated labs that use robotics and machine learning to help automate and accelerate scientific discoveries. Berkeley’s Lawrence National Lab is building out a new facility right now to do experiments for organic chemistry using robotics.

That’s what I’m hoping to be a part of at Berkeley.

So far in my journey as a student and entrepreneur, I’ve found ways to use my personal experiences and passions as motivation to solve really challenging problems.

And I think that’s what we should be doing more of — following through on our passions and using our talents to grow, learn and innovate.

For a lot of people my age, we are still trying to find what our purpose is. But in that process, I think you can still make a difference. You don’t have to wait. Strive to be a pioneer in anything you are passionate about.

In doing that, I think you will ultimately find purpose and your place in the world.