‘Grief can coexist with happiness’: How one student found her way to UC Berkeley

After a sudden family tragedy in 2021, college seemed like a faraway dream to Coachella Valley High School sophomore Natalie Araujo.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

September 26, 2023

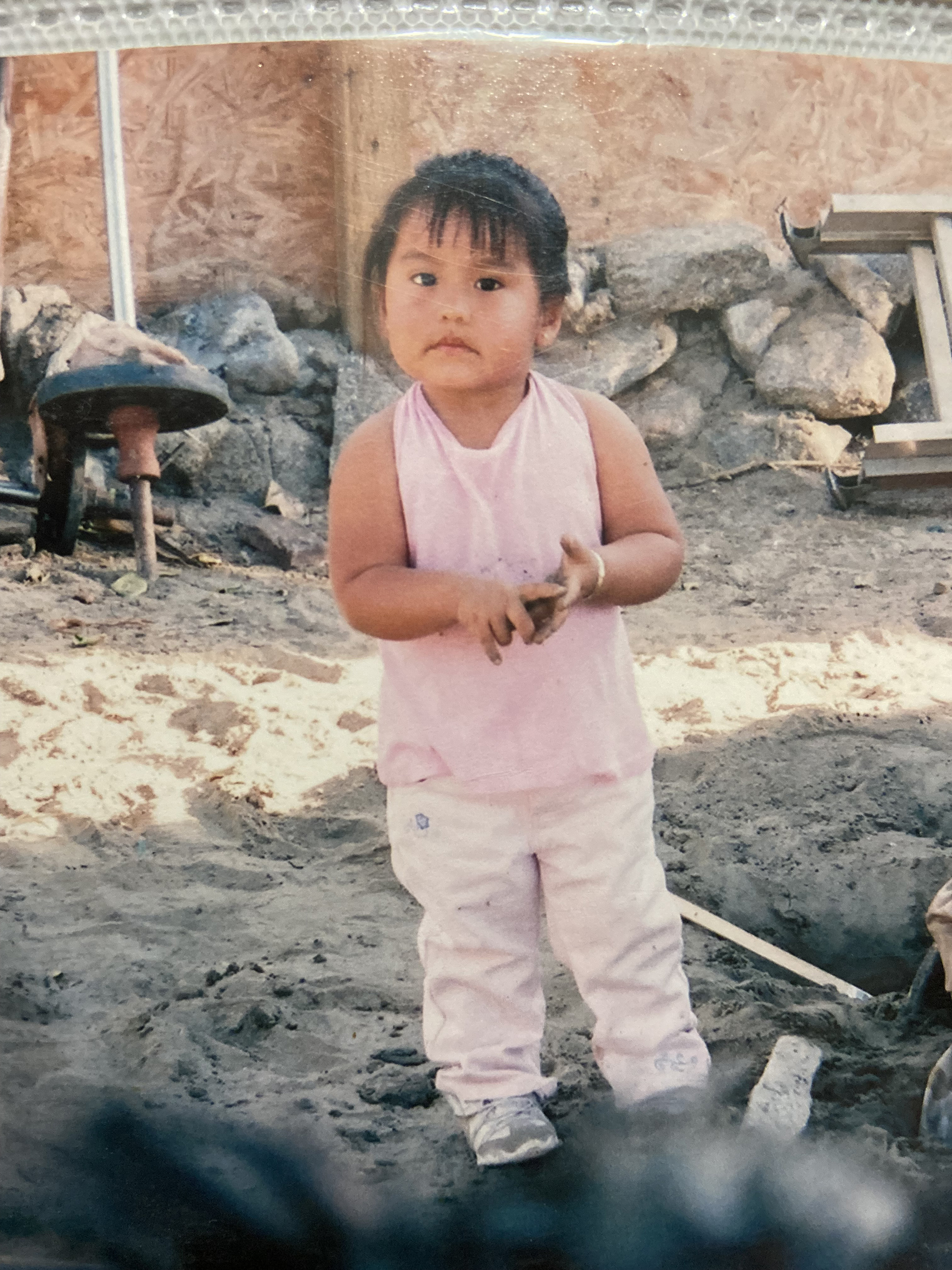

As a young kid growing up in Southern California’s Coachella Valley, Natalie Araujo didn’t like school. She felt unwelcome, like an outsider looking into a world she’d never fit into, no matter how hard she tried.

Courtesy of Natalie Araujo

In first grade, she often stayed home to look after her younger brother, Adrian, as her parents worked long hours in low-wage jobs — her mom, in an agricultural factory and her dad, in construction. When the school district mandated that she start attending school, not only was she behind academically, but she also didn’t speak English.

“I couldn’t understand the teachers or the other kids,” she said. “I’d get so frustrated, I’d just fall asleep.”

In second grade, things began to turn around. She had a bilingual teacher, Ms. Ramirez, and was enrolled in an English language program. School slowly became a place where she felt she could thrive. As the years went on, she fell in love with history and math, and got involved in all sorts of activities. She joined the debate and dance teams, was part of an engineering and renewable energy program, and competed in the national KidWind Challenge with her team.

Although she had a lot of responsibility at home as the oldest daughter in a traditional Mexican household, her parents always made sure she put her schoolwork first. And it paid off: She’s a first-year student at UC Berkeley, and the first in her family to go to college.

“I never thought I’d learn English as a kid, and I never imagined that I’d be at a school like Berkeley,” she said.

But just two years ago, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and a sudden family tragedy, her dream of going to college felt so far away, and she wasn’t sure she’d ever make it.

At 15, she lost one of her biggest supporters

Both of Araujo’s parents grew up in Mexico. Her dad, Porfirio, was born in Chicago, but moved back to the central Mexican city of Guanajuato after his parents were deported. Years later, his family moved back to the U.S. Her mom, Idalia, was born in Puebla, the second of five children. She received a full ride scholarship to a Mexican university, but she couldn’t afford to attend. Instead, she came to the U.S. at 17 to work and send money home to support her younger siblings’ education.

Idalia and Porfirio met in the 1990s in the Eastern Coachella Valley, a rural, arid desert in Southern California crisscrossed with vineyards, orchards and fields growing all sorts of produce, from dates and bell peppers to grapes, melons and broccoli. There, about half of the mostly Latinx residents are at the poverty level and have less than a ninth grade education.

Courtesy of Natalie Araujo

Her dad, a self-proclaimed “straight F student” (F stood for “fantastic,” he’d say), graduated from continuation school as a young adult. He’d joke with his kids that he didn’t use his brain so that they could. “He always had the dream that I would graduate with honors,” Araujo said.

After he had a stroke in 2018, her dad went on disability and stayed home, where he and Araujo spent hours every day cooking together. “He taught me how to cook everything, from stir fry, soup and tacos dorados to his famous pozole,” she said.

In March 2020, when the pandemic temporarily shut down companies and schools, Araujo’s mom, who worked at Marriott’s Desert Spring Villas in Palm Desert, was out of a job for several months. She returned in December, and a month later tested positive for COVID.

Araujo got it next. Then, her brother.

The family worried about Porfirio. After his stroke, he’d gone on dialysis to treat his diabetes, which he’d had — but not been treated for — since he was a teenager. They begged him, often unsuccessfully, to wear a mask and stay in a back room while they recovered.

Courtesy of Natalie Araujo

In January 2021, Araujo, whose high school had switched to online learning, was sitting on the couch next to her dad, writing an essay for her honors course in multicultural literature. Suddenly, he started convulsing.

“I got really scared,” Natalie said. “I called 911 and told them what happened, that there was stuff coming out of his mouth. I didn’t know what was going on. I just said, ‘Please hurry!’”

Twenty minutes later, emergency responders arrived and asked the family to stand back, to avoid exposing the team to COVID, even though they’d fully recovered. “We watched from afar as they put my dad on a stretcher, asked him questions that he could barely respond to, then took him away in the ambulance,” she said.

Over the next week, Araujo and her mom called the hospital three times a day to check on him, but would get vague assurances that he was “doing fine.” He’d been transferred to Desert Regional Medical Center in Palm Springs, an hour away, because the first hospital couldn’t give him dialysis. But still, no matter how much they pleaded, he never received it.

Early one morning, her dad called and woke up the family, all asleep in the same room.

“And he tells us, ‘Hi, I’m good,’ and he starts laughing,” said Araujo. “As soon as he starts laughing, he starts coughing, and we just hear so much commotion. We start hearing beeps and monitors and people yelling, and the hospital hangs up on us.”

Thirty minutes later, the hospital called back and told them his oxygen levels had plummeted, and that he’d been intubated.

Four days later, Araujo and her mom got a call saying his heart was failing, and he was unconscious. His heart had stopped more than once, and they’d had to resuscitate him.

“They told us, ‘He’s not going to make it.’”

Araujo and her family were devastated. They convinced the hospital to let them say goodbye to him in person, which they did wearing robes, gloves and masks. “We touched him, and he was really cold, like ice,” said Araujo.

His heart stopped again, and a nurse pulled them out of the room as the medical team revived him. After speaking to a doctor, the family decided that if his heart stopped another time, that he not be resuscitated. That they’d let him go.

A few minutes later, a nurse told them, “He’s gone.”

“I’m always translating for my mom,” said Araujo. “But this was the … saddest translation I’ve ever had to make.”

At 15, as a sophomore, Araujo had lost one of her biggest supporters, who always made sure she focused on succeeding at school. But now, graduating was the last thing on her mind.

‘You have to live for your dad’

After her dad died, Araujo stopped going to school.

“My grades dropped from all As to Ds and Fs. I just couldn’t focus. It was horrible,” she said. “I couldn’t sleep on my own. I was having nightmares. I saw a therapist every day. It was a really bad time.”

In April, two weeks before the end of the quarter, Araujo went back to school. She tried to catch up, but was too far behind and wasn’t sure what to do. With the urging of her mom, she decided to talk to her teachers and do whatever it took to get her grades back up.

“My mom was always there for me and my brother,” she said. “She told us, ‘You have to live for your dad. You have to make him proud. You have to continue your education.’”

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

After weighing her options, Araujo requested an incomplete, and in the next quarter, she took six classes — twice as many as everyone else — and went to school on Saturdays.

“It was really hard, at that point,” she said. “But I was able to do it. I got As in all three classes I had to take. It was three months of rigorous work. I’d always be in office hours, asking for help with math and chemistry. I was the student I never thought I’d be. Before that, I was always really shy, I never wanted to ask for help. But at that point, it wasn’t about how I felt. It was about persevering and continuing.

“I guess it wasn’t the most healthy, keeping myself really, really busy. Whenever I wasn’t busy, I’d get a rush of emotions again. But I was able to make it through those three months, and I got a 4.7 GPA as a sophomore, so it worked out.”

Courtesy of Natalie Araujo

She went on to thrive in school again, pushing for better school safety measures and a change in the school’s dress code to be less sexualized and more gender inclusive. She also worked with her high school’s Young Women’s Empowerment Club to fight for better access for students to free menstrual products, pursuant to California Assembly Bill 367, resulting in the placement of several menstrual product stations in the school, including the boys’ bathrooms for trans students.

Next, she had to figure out college. And she had no idea where to start.

Berkeley felt like ‘a big family’

Like many students in the Eastern Coachella Valley, Araujo didn’t have family members who could advise her on college. So she joined Upward Bound, a federal program that prepares students for college entrance. As part of the program, Araujo and other students went on a summer tour of UCLA and a few Cal State campuses, and were assisted with the college application process.

Araujo ended up applying to eight universities — four UC campuses, including UCLA and UC Berkeley, and four Cal State schools.

To her surprise, she got into all of them.

After weighing her options and comparing financial aid packages, it came down to UCLA and Berkeley. She was leaning toward UCLA because she’d already toured the campus and her best friend, Melissa, was going there.

But then in March 2023, members of a Cal Alumni Association chapter, Cal Bears in the Desert, visited her high school to promote Berkeley — a school she knew had a great reputation, but didn’t know much about otherwise.

At a presentation, Cal Bears in the Desert passed out swag and folders with useful resources, like a calendar with important upcoming dates and information about Senior Weekend, a four-day trip to Berkeley in April for more than 400 recently admitted high school seniors to get a feel of the campus. One of the presenters was a student from Coachella Valley with a degree in legal studies, a field Araujo was especially interested in.

“It was the first time I heard about Berkeley, besides what I’d learned on my own,” said Araujo. “I had been researching, trying to find out as much as I could, but I was still confused about the whole process. So when they came to talk to us, it made me want to know more about the school. And to meet someone from my community who had gone to the school and who spoke highly of the legal studies program was really impactful.”

Luisa Armijo, who formed Cal Bears in the Desert in 2013 with her husband, Oscar, knows that high school students from the valley who are accepted to schools like Berkeley face barriers to making college a reality.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

“We’ve had to really educate Cal about resources many students from the Coachella Valley need,” she said, “and then provide resources for these students, as well.”

That April, Araujo was planning on going to Senior Weekend, but didn’t have a way to get to the airport. So she, and other students in the Coachella Valley who didn’t have transportation, got in touch with Cal Bears in the Desert, and the group arranged for a shuttle to take them to and from the airport.

“So I was able to go on that trip, and I was able to find out that I really, really loved Berkeley, and to meet other students from the desert who were also going to go to Berkeley,” she said.

On campus, Araujo visited the Raíces Recruitment and Retention Center, which sends Berkeley students on recruitment trips to increase the number of Latinx high school students who attend college, and also attended ethnic studies lectures. And she went to Cal Day, Berkeley’s annual open house for newly admitted students.

Courtesy of Natalie Araujo

“Ultimately, what made me decide on UC Berkeley was the environment I felt there,” she said. “It was a family. It felt like a big, big family. Each day, I fell more and more in love.”

Araujo is one of a record 83 high school and community college transfer students from the Coachella Valley who were accepted to Berkeley for fall 2023. Of those, 46 decided to attend — the highest rate from the region to date. Cal Bears in the Desert provided outreach to every student admitted.

Everything was falling into place for Araujo: Berkeley felt like the right school for her, and she felt up for the challenge.

In June 2023, Araujo graduated from Coachella Valley High School with honors and a 4.4 GPA. At Berkeley, she plans to major in legal studies to pursue a career that combines her love of debate and of renewable energy. Maybe she’ll be an environmental lawyer, she thinks.

But whatever she does, she’s proud of how far she has come, and knows her dad would be, too.

“I’ve learned that grief can coexist with happiness,” she said. “So when I feel sad about my father not being there in person, I’ve learned to feel happy about how much I’ve accomplished, with my family by my side, spiritually and physically.”

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley