Berkeley Talks: Chinese activist Ai WeiWei on art, exile and politics

"It's not that I intentionally try to create something or to crystallize something, but rather I've been put in extreme conditions, and I have to focus on dealing with those situations," he says.

October 6, 2023

Follow Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. See all Berkeley Talks.

[Music: Silver Lanyard by Blue Dot Sessions]

Intro: This is Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can follow Berkeley Talks wherever you listen to your podcasts. New episodes come out every other Friday. Also, we have another podcast, Berkeley Voices, that shares stories of people at UC Berkeley and the work that they do on and off campus.

[Music fades out]

Orville Schell: Well, thank you all for coming, and thank you, Weiwei, for coming, and Peter as well. Weiwei wrote this wonderful book, A Thousand Years of Joys and Sorrows, about his life. We’ll talk about that and many other things. Before we do, in 1938, when Pablo Casals went into exile, and we should remember Weiwei’s in exile, too, he went to the French Pyrenees to escape.

When Casals arrived there in a little town in the mountains, every morning, he got up and he played a movement from Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites. And he said that this was a benediction on his house of exile. Since this is the Yom Kippur and it’s also the Christian Sabbath, let’s start with a little music ourselves just to calm ourselves. Let’s listen to the Benedictus from the Missa Solemnis by Beethoven. Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini, Blessed are they who come in the name of the Lord. It’s sung by Gundula Janowitz, Fritz Wunderlich, Christa Ludwig, and Walter Berry with Herbert von Karajan conducting. So let’s listen and then we’ll start our conversation.

Let’s begin. In 2011, before Weiwei left China, he was imprisoned. My wife and I and a photographer friend, Clifford Ross, went over to Weiwei’s studio in Beijing, and it was a lovely sunny day and we did a little photographing, or Clifford did, of his studio. So I thought let’s start with that and maybe, Weiwei, tell us what we’re looking at as we see these pictures. They’ll be on the monitor there. So you grab your mic and you can maybe walk us through what we’re looking at here if we put the slides up, please.

Ai Weiwei: So I should talk, right?

Orville Schell: That’s why you’re here, Weiwei.

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. Because I was trying to take a nap when there’s music there. But I thought it’s not proper to take a nap. OK. That’s an image I took, I think, 1981 or ’82 when I was in Brooklyn, Winlesberg in Brooklyn. It was grocery store. Behind the [inaudible] was piles of the paper towels, I believe. But for someone come from China, from a very poor communist society, to see Americans have used so much paper and just for the waste, I cannot believe it because, as a son of a writer, my father never had a nice piece of white paper to write on. He has to write on some wasted papers. So for me, that is really American. You can waste tons of papers. That’s the image.

Orville Schell: So you were here for 12 years, was it?

Ai Weiwei: Huh?

Orville Schell: You were in America for 12 years?

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. I spent about 12 years in United States, actually one year in California in Berkeley. I was there to study my English in Berkeley adult school.

Audience: (Applause) Woo! Woo!

Ai Weiwei: I don’t know if that school still existing, but it’s very friendly and they accept students from everywhere, and the teacher is very nice, teach us music, such as “Old McDonald Have a Farm.” So we had a great time there.

Orville Schell: So what are we looking at here? Tell us what’s going on here with this slide.

Ai Weiwei: OK. That’s a image I wear a T-shirt, which made by Julian Schnabel, the artist when I was disappeared in 2011. So I think he as an artist, he made this response and he printed a lot of T-shirts and gave to people. I really appreciate this kind of support. I guess that’s…

OK. These are two images. Well, there’s colored… OK. OK. The one black and white image behind is I use a hammer, crash imperial blue and the white vases. So it’s a kind of ridiculous act, but I do that kind of act all the time. Yeah. So you took all those photos?

Orville Schell: You probably don’t remember him, Clifford Ross?

Ai Weiwei: I don’t know any of them.

Orville Schell: Yeah. Well, you probably don’t even remember the day we came over and he just started taking photographs.

Ai Weiwei: Besides I’m under very strong surveillance of the authority and occasionally we have visitors, they also take those photos. I never even noticed.

Orville Schell: Well, you all should know that since Weiwei was under surveillance by cameras outside his compound, tell them about the camera that you sculpted.

Ai Weiwei: Well, in front of my compound, there’s about 25 surveilling cameras. I ask them why you have to have so many? You only need one for each door. But they told me they have so many different hierarchies, some controlled by local police, some controlled by state police, and maybe it is all people are sharing this banquet to look at somebody else’s life. So I’m wondering how to help them. I realized they don’t have cameras in my bedroom or in my office. So I put cameras right above my bed and also above my working table, and I start 24 hours livestream and attract millions people watch it globally. Then it only lasted three days. The security people called me and said, “Weiwei, you have to shut it off.” I said, “What do you want? There’s some corners you cannot even see it.” But they cannot bear with this notion you are reveal everything to them rather than they pick on you, which is completely a different kind of level of philosophy. And they just said, “You have to shut it off.” I said, “OK.” Yeah.

Orville Schell: OK. This is just in more of your studio. You obviously love cats.

Ai Weiwei: We have a lot of cats and dogs because at that time, I think after the first pandemic 2003, there’s a SARS, and that time people start to blame all those disease come from animals. You can see people driving on the highway threw their pets out of their car windows. It’s thinkable. Also we know people are collecting those pets to guangio for some kind of special delicacy dishes. They’re going to use it. So we seize the whole car of the cats. There’s about over 400 of them. Because there’s no policy to protect the animals, ended up, I have to collect 40 of them just to feed them. So suddenly I have 40 more cats in my home. They’re all nice. Yeah, they all have their characters there. I will say they’re a little bit better than human beings. Yeah.

Yeah. That’s also a image of my studio. You see there’s just nothing there. My studio is only studio or art studio, if you see, then into now you don’t see my artworks. Sometimes you see cats and dogs and some plants. Because I’m very shy with my work. I never think I’m a good artist. I don’t want to look at work once finished. I’d rather it just in the box or going to some museum shows. But I will not ruin my home with my works.

I don’t know. What is this?

Orville Schell: I think it must be your library or in your…

Ai Weiwei: Oh, OK. That’s the books. You can see those books are not vertical, but horizontally piled up. And that means I never read them.

Orville Schell: Are they still there? Is your studio still…

Ai Weiwei: Still exactly like this. I never changed since I’m moving, everything put there, nobody move it.

Orville Schell: But is it there now?

Ai Weiwei: Because cats also don’t read.

Yeah, that’s my studio. You see the wall is empty. A lot of the sunshine come in from this window. After I build this house, I become very well known in Chinese architecture world. The people think I’m a person can be a spokesperson for new lifestyle, new aesthetics. So that got me involved in design, the National Stadium with Herzog de Meuron in Switzerland. Yeah, that gradually get me into trouble, but I don’t even know at this moment. I’m really just trying to solving problems relating to architecture. But of course the architecture is very political acting in China. You start to know so many layers you would never even think about, the government, the regulation and all those policies. Yeah. That’s the beginning of the trouble.

Oh, you take photo of my bedroom. OK. That’s cats on there. That’s the only thing interesting is you can see cats dominates everywhere.

I don’t know. What is that? Oh. It’s a marble apple, I think.

Orville Schell: Is that your sculpture? I think it is.

Ai Weiwei: No, my craftman, they always try to impress me. They always want to be artistic. So they gave me those objects so they think I should develop my art in that way, and…

Orville Schell: Well, we’ll click it off.

Ai Weiwei: Those are just really casual photos. I don’t know. But it’s very real. It’s porcelain. It’s a craft. It’s made of porcelain.

That’s one known photo about, I think, it’s White House. Yeah. It’s White House. Yeah. That’s 1995. I had a chance to visit Washington, DC. I hate to take… How do you take a photo in front of this monument? My photo is always like that. After years, I have many, many photos with my left finger and it become artwork later. It’s so easy. You don’t have to go to school to learn those skills. True. I mean, school teacher will never teach you those things. They do this practice, but they don’t teach you.

Yeah. This is a table come from… I cut a Ming Dynasty-style table and I banged it and banged again. So one leg is missing. Would be a three-leg table and two leg. It just on the corner. The corner is always empty. It’s always problematic space. So I think this table give the corner some kind of strange, strange attention.

That’s sunflower seats. Those are big boxes. Actually, the actual one is very small. It’s about one-and-a-half or less than two centimeters long. I did over 100 million of them with local craftman, mostly women’s. 1,600 of the women’s worked for two years. This image doesn’t really show.

Orville Schell: They ended up in the Tate, didn’t they, Museum?

Ai Weiwei: Yeah, and…

Orville Schell: Yeah. And other places.

Ai Weiwei: And Tate exhibition. So I don’t know. Yeah.

Orville Schell: Well, we’ve seen that one. Let’s see here. More sunflower seeds. Let’s click along here. More studio. Are you a Buddhist?

Ai Weiwei: My studio, if you’re walking, it’s almost like someone just moved out or before someone moves in. It’s completely lost. What’s going on here? Those are some antiquity. I collects a lot of antiquities. Yeah, and that’s… Well, it’s all ridiculous.

Orville Schell: So that gives a little sense of Weiwei’s life, lost. So Peter, what great questions do you are on your mind to pose to Weiwei? I mean, you both have been in art and politics for so long.

Peter Sellars: Weiwei, for me, one of the most moving things about your art is that in this long process, you found a way to move past art as an object and art as an aesthetic activity primarily, but instead really to solve actual problems in a real way because the world we’re living in, the old solutions are not working and the solutions have to be creative. They have to be new at the same time. They have to come from some deep past, and you’re holding all those things together. But some of your most amazing art projects are really gathering people to solve real problems and creating a new motivation, a new possibility, a new reason to gather, a new way to gather that’s suddenly enjoyable with open possibilities and not already predetermined.

Would you just talk about some of the ways you moved into these situations and made an artwork and a process that crystallized a moment in time, but also maybe a set of possibilities next? I mean, here in San Francisco, your installation on Alcatraz was one of the most overwhelming experiences. The people visiting were liberated from being consumers and invited to be something else, citizens and beings of the world, and to be in connection with the next step of their life and other people’s lives.

Ai Weiwei: Well, as an artist, normally people call me as artist or activist, and I often being forced into one condition. It’s not that I intentionally to be trying to create something or to crystallize something, but the rather I’ve been put in extreme conditions, but I have to focus in dealing with those situation. Normally, I don’t accept the easy answer. So I think I have to find a language to illustrate my expression, and it come out certain ideas or materials. Normally we can call it art, or I don’t think my art really look like art, but still it’s hard to category it. It’s not a scientific conclusion, but it’s easier to call something useless as art. Yes, that’s what I do. I’m a bit ashamed about it because everything in real life, it has a purpose. I have clear problems and solutions, but the art is not really about it. It’s rather create problems after problems. So yeah, that’s what I do.

Peter Sellars: And this idea of, first of all, one of the most powerful things is the artist is not present, and yet the artist is very present, the combination of your absence and your presence and the degree to which right now with prisoners of conscience all over the world in all kinds of contexts, this idea of people who have been silenced, but in fact that silencing becomes very powerful and creates enormous amount of attention and presence. You’ve worked with that really, really skillfully in each of your situations. Most artists don’t think of that because a lot of the art world is about the personality of this or that artist. You took everything past that place. Would you maybe talk a little bit about how you arrived at that? I mean, of course as you said, life imposed certain limitations when you were arrested and so on, but the way that became powerful all over the world.

Ai Weiwei: My case is very much like… I don’t know I can learn a lesson from my past because it’s almost like you cannot repeat it. It’s just given conditions and I react to it. And by mistaking people also misunderstood it, so I become what happened today. It doesn’t have to be this way. I can be someone just hanging around and sit on a bench, enjoy sunshine like in California, many, many people you see on the street corner or in the park. I see myself more belong to those people. So it’s full of a surprise. That’s why I’m not very comfortable. But I’m still alive and I’ve still been put in very strange circumstance and also I have to deal with it.

Orville Schell: Weiwei, let me ask you, obviously your life was a very difficult one. For those of you who haven’t read this really wonderful, wonderful book, he spent first basically 20 years of your life in prison camp with his father who was the 20th century’s most renowned, well-known poet. I’m wondering, how did that impact who you are as a person, your art, and how you are in the world now? What was the effect of those first two decades?

Ai Weiwei: Well, my father studied in Paris. I always have to mention that because that’s where I come from. He in the ’20s right after he come back from Paris, he was sentenced for six years for some kind of crime called subversions of state power, similar as today, but that was nationalist party.

Orville Schell: This is Chiang Kai-shek’s, though.

Ai Weiwei: Chiang Kai-shek’s party. Later he joined the revolution under the already established, this new government. Then immediately Chairman Mao realized what really threatens his power as those intellectuals.

Orville Schell: Didn’t he actually have conversations with Mao where he said that art was not something that could be controlled or should be controlled by the state, and Mao was displeased with his expression.

Ai Weiwei: It’s the same argument we repeat every year and even ’til today.

Orville Schell: Maybe put this a little closer. I don’t know if people can hear.

Ai Weiwei: My father believed the integrity of a writer and it’s not just to say something nice about society, but rather criticizing. That’s the most important character of a so-called intellectual. That means you have ability to criticize the condition. Of course, communists cannot accept any kind, not even criticizing, even just attitude of that cannot be accepted. So he was crushed under this so-called anti-rightist movement, which punished over half a million of intellectuals. There’s no such big number of intellectuals at that time, so included school teachers or university students, whoever raised some questions about authority.

He was one of the biggest rightists, they call him, being sent to very remote area northeast and then later northwest, which is the place Xinjiang, we often heard about. Now they have this kind of reeducation camps for Uyghurs. So long before reeducation camp for Uyghurs, we are the first generation being reeducated. That’s the year I was born, 1957. Immediately when I become as a boy, I start to realize my father is an enemy of the state. Of course, I would never understand how can a writer become enemy of a state. The state is so big and powerful, and also they call him enemy of the people, enemy of the party. So he’s very strange. They have to category state people and the party different. So he’s like three enemies. But basically nobody know what kind of crime he have done, but he’s really heavily punished.

Now if I think back, I am not a distant when growing up, but I was forced to become a distant when I was born because we are someone almost like disease; the society cannot accept. Every movement or language being watched, examined, or even reported. So it can bring tremendous pressure to the family and is a very surreal condition. You don’t see it in reality. But funny enough, you still see it in today’s political practice in China, people still trying to find spies. They still try to encourage people reporting on other people, which is really a social disease and a social political disease.

Orville Schell: I wonder, as a young child, every child wants to respect and be accepted by and love their parents. And yet if your parents are considered enemies of the state, it creates an incredible conflict because… I wonder, how did you experience that? Did you ever wish your father was different? And how did you deal with this thing of having your father being an enemy?

Ai Weiwei: Well, it forced me to take sides because teacher or students look at you very strange way to say you’re either on the side of the people or you’re on the side of your father, but still make me feel my father is so powerful but doing nothing, but the whole society is against him. So maybe that gave me some understanding of the intellectual power, but nothing you can do. It’s like standing in the middle of a rain, you get wet, now everybody get wet.

Orville Schell: Peter, you’re very interested in Buddhism. I’m kind of curious whether this guy’s a Buddhist. But maybe you should ask that question, or where is religion in all of this?

Peter Sellars: Well, you’re just getting to really deep question of how to live with almost nothing growing up for those years with very little food, very little human contact in a certain way, and absolutely nothing to buy or sell or anything like that. So you’re having to find some strength inside yourself. Your father is representing a certain kind of strength going through humiliation after humiliation and not speaking about it. That’s a very rare childhood.

Ai Weiwei: Well, I know very little about Buddhism. But I think one of the Buddhist highest spiritual condition is losing this kind of, we call it wúwǒ, means the self not existed. Is that a right interpretation, I don’t know. It’s just trying to overcome this kind of selfness, but I don’t know is the right interpretation.

But actually when we grew up, the whole society of communist control really achieved this wúwǒ condition because we never say “I want to do something.” That “I” doesn’t exist. We only say we or we say the collectively people. So nobody has birthdays. My father, mother and us, they never remember my birthdays. That’s why I created my own birthday. And then now ended up, I have three birthdays. On Twitter each year, people greeting me for happy birthday. But many people knew Twitter, commenters, will say, “He’s just had birthdays three months ago? I don’t even know how to explain this.” So we really got into this self not existent stage, which I think is the highest stage of Buddhism, but achieved by a state. It was not by us.

Peter Sellars: Did you as a child ever think about making art or make a gesture as an artist?

Ai Weiwei: Really not. I never been encouraged to make art because see how damaged art has been down to all the artists and the intellectuals to China, to my family. So my father never encouraged me to say doing art. He only asked me to help him to burn all his art books or poetry collections. So I helped him put all those books in fire. Art is being considered as evil in the society. So the best wishes for parents like my father, a top intellectual would say, “You should be honest worker.” That means you have to get your hands dirty and to be really tired, working not in the factory because under my family’s situation, we are not trusted. So we cannot touch the machine. The machines kind of holy in China at that time. So we only can work in the farming area because you cannot do damage to earth, actually you can really do damage to earth today. But at that time to work in the farm, that’s the only possibility.

So when I growing up, I never really think I can become a artist. That’s very strange. Actually today, I still not formally believe I’m a artist. I do something similar of art.

Peter Sellars: Were you reading your father’s poems as you were growing up? Did you read your father’s poems as you were growing up? Did you put them in your own memory?

Ai Weiwei: No. His poems are being destroyed only till very late when I’m 20 years old. When Nixon visited China, then his situation become looser. They said, “You can go back to the capital to try to cure.” He has eye problem so he can get some kind of medicine treatment. So there’s reader sent back his collect poetry book, said, “I have been hiding this book under the rice pole,” the pole they put the rice in there, they hide the book under there so nobody can see it. So they sent back those books that I realized he writes so much. He’s a great poet.

Orville Schell: As I remember, Weiwei, that as China began to open up under Deng Xiaoping and Westerners began to come in, they were asking, where is Ai-Ching, your father? And then the party thought, “Well, we better produce Ai-Ching,” because he was a well-known figure. And then they gave you an nice house in Beijing. Tell how that happened.

Ai Weiwei: Well, the story I heard is in China, nothing’s clear. You can never really find the solid facts. Doesn’t matter how high your level is, even. Even Deng Xiaoping, nobody’s clear what really he has been doing and he write many, many self-criticizing papers to the party for him to regain the power. Long, long letters, but nobody know what he’s writing, what he did writing. So same as my father, even he passed away while writing my book, I ask my mom, I said, “You are so respected today and can you ask the party to release his…” How do you call this kind of [Chinese langauge]?

Peter Sellars: That means the personal…

Orville Schell: His dossier.

Ai Weiwei: Huh?

Orville Schell: His dossier, his political dossier that…

Ai Weiwei: Yeah, he’s dead and he’s very respected. “Can you release that so I can get some historical facts to see how he confessed?” Because every political movement he has to write a confessed paper. This is a requirement. Otherwise it is very, very difficult situation. But they told my mom, they said, “You will never have a chance to see those materials.” So in China, basically nobody have a chance to see any of these kind of materials. That’s what made China very poetic. The people from history, people write poetries about the moon until U.S. landed in the moon, then destroyed all those poetries. We realize the moon just nothing. But before all our literature are related to the moon, the beautiful moon there. So yeah, in China it’s hard to get any facts. And so what’s the question?

Orville Schell: Well, I wonder how does one survive 20 years in the foremost formative period, how does that affect you today and what you do in your art and why you do it?

Ai Weiwei: Why do art?

Orville Schell: No. How did the early years of your life when you were living with your father in these very difficult circumstances and basically in prison camps, how do you think it affects you today and what you do as a human being and as an artist?

Ai Weiwei: Well, it’s almost like police interrogations. Something I can’t really answer is it happened that way. It’s beyond my control and I’m victimized by something I don’t even know. Yeah.

Orville Schell: Well, that’s a showstopper. Peter?

Peter Sellars: Weiwei, we’re in a place where when we walk down the street here, as you said, there are lots of people living on the sidewalk. There are lots of people who don’t have something to eat. There are lots of people who have nowhere to live and no contact with their families. And here in San Francisco, here in the Bay Area, it’s normal. You just keep walking. One of the most powerful things you did was not keep walking with the question of refugees and people trapped in these nightmare immigration prisons and holding cells and detention centers, people urgently leaving everything that they value to come to a place that they don’t understand, but knowing that they have no future where they grew up, and here they are in an unbelievably vulnerable situation. At the same time, these are people clearly of courage and determination and they’re arrived to have their lives completely shut down. And you didn’t just keep walking. You made years of your life a huge project of saying, “What’s going on here?”

Ai Weiwei: I’m sorry. This is only conversation no water is on the table. And it is rare. Normally I know California may lack in the water…

Orville Schell: We’ll see if we can summon some waters.

Ai Weiwei: But anyhow, since I grew up in the quite difficult situation, it’s almost not speakable what is difficult situation. It’s because the difficult situation is something you cannot really speak about. So when I realized those, a lot of unfortunate human beings, when I see…

When I see so many people have to leave their home to come to Europe or United States, and so I feel it’s not enough just to watch on television or listen to the news. I have to go to the real location, how they landed in Europe, which is Lesbos. Over half a million people landed in a little Greek island because it’s very close to Turkey. So when I see how those people climb up, those women or children, the fortunate ones can still approach the beach and you can recognize they don’t belong to Europe. They are really dressed differently; they speak different language; they have a very different behaving when they come out to the land. They really still worships their god and they still very different, the behaving, then make me feel the crisis are much bigger than normally we call the refugee crisis. But I think that is human crisis.

I decide to go across to the other side, to Turkey, to other locations which have historic or current refugee conditions. I want to organize the team to start to make a film, to go into Pakistan or Iraq or Lebanon, Jordan, and Jerusalem, Mexico, many, many locations where have a lot of refugees. We visit about the 40 largest refugee camps. I interviewed over hundreds refugee personally myself, just to repeatedly listen to their story.

Basically, it’s just one story. They have to leave their home, the beloved home. They could be rich or poor. But they have to leave because they want their children in a more safe ground or they want their parents can have a better life. So those are very basic humans emotions, and they are very brave. They take chance and many of them are drowned in the ocean, but still people flooding into Europe.

But on this side in Europe, they’re being refused. They’re being really smeared and they use all kind of wrong descriptions, and they’re trying to come out policy to push them away. So that is basically a act for help me to understand the global politics, human rights record, to understand those are not so easy because I was focusing in China, that after three years of making three films about refugees, then gave me more better or profound understanding about who are they and why they become refugees and the way the West have responsibility to help or to accept them.

But still now refugee situation changed a lot. Even in Europe between the Russian and the Ukraine wars, you have refugees produced right in Europe, Ukrainian refugees, still hundred thousands of them have to leave their home. The refugee number already over a hundred million doubled the size when I started to pay attention. So I’m sure the refugee number was still going up because the environmental problem, the water problem or famine or so many wars are still going on, and the more these kind of conflicts can happen.

So the conclusions are how can we deal with the situation? I think the only way is to stop produce those disasters. Those old disasters are made by human and by government, and that has to be stopped; otherwise, it’s not going to be bright future. We all know we are at the age of the World War III people think that’s not realistic. It’s very realistic. The nuclear bombs is not just going to be dropped on Hiroshima again. It is going to be dropped in many nations. It will be much more casualties or maybe it will be the end of the humanity.

So seems people are not really act on stop the war and stop and destroy all those nuclear bombs. Why? I don’t know why, what’s wrong with people? If you talk about building democracy or freedom of society, why in the very essential issues we cannot be united? We cannot say just stop and destroy all those nuclear weapons. It was good for all the children or people. Doesn’t matter you men or women or in between. It’s good for you. So we all have to do is just solve the current problems and before it becomes something not controllable.

Orville Schell: You mention that you are concerned about a broader war. Do you fear that it’s possible the United States and China could end up at war? Yeah.

Ai Weiwei: I don’t think United States and China would have a war, honestly, I think. But the war is never predictable. It happens. It can be triggered by some other reasons and some other excuse. But of course, it seems it’s no benefit just to have a war between these very two big mega nations. But some smaller conflicts can trigger a big war.

Orville Schell: Are you optimistic or pessimistic?

Ai Weiwei: I have no feeling.

Peter Sellars: No, for me, one of the most important things I think in human life is frequently that one discovers oneself far from where one grew up, and you meet many parts of yourself in a foreign country when you’re traveling, when you’re exposed to other worlds. As you know, most people on earth are not allowed to travel anymore. They can’t get a visa. Certain people are allowed to travel from certain countries, and most of the rest of the world is not allowed to travel. This idea of finding some part of who you are in a foreign place, would you just talk about what it was like to come from the super intense moment in China to the ’80s in New York City and meeting the artist of yourself in New York?

Ai Weiwei: I don’t know that is a question.

Peter Sellars: Just to say the ’80s was an incredible experience in your life coming after…

Ai Weiwei: Well, the ’80s, I was a student. I speak no English. I tried to survive in New York. I believe I can become a Picasso. I told my mom why I left China. I said, “Don’t worry, I will become a Picasso.” And now, very soon, I realize I don’t want to become a Picasso. So I changed my mind but I never told my parents, and they don’t trust me anyway. Then I don’t know what to do in the United States because I don’t have this American dream. I normally don’t have a dream. So of course when they talk about the American dream, I never really know what is American dream. For me, someone growing up in the communist society, those dreams seems a little bit naive. So I think I never really believed this.

But still I love to have the so-called individualism or to have a liberty. But I realize the liberty is if you die in your apartment, nobody care. Only the landlords, they come to collect your rent, they find out, “Oh, smelling is so bad,” then they’ll open the door of someone dead. So seems quite a society, not very human, I would say, of course. Capitalism is not supposed to be very human. It’s just a struggle and a competition.

So I hanging around. I found no purpose of my life. That’s best time because I found no purpose of my life, my big finding is my life has no purpose. And that helped me a lot and maybe that helped me to become someone today.

Peter Sellars: One of my favorite projects that I’ve ever, ever, ever heard of in my life is the project you made in Germany that was getting visas for a lot of people from China to come visit Germany. Remind me the name of the project. It was for Castle, I think. Was it for Documenta? You made it…

Ai Weiwei: Oh, yes.

Peter Sellars: You made this project which got all of these people visas.

Ai Weiwei: Fairytale.

Peter Sellars: It’s Fairytale. And all these people, Chinese people came to Germany and everybody said, “Wait a minute, what’s the point of this?” For me, it’s the most inspiring project I’ve ever heard of. I am so moved by this project. It’s so beautiful, Weiwei.

Ai Weiwei: Thank you. You’re the only one probably still remember it. I really appreciate it because for me that’s also a project need to be… It’s a Fairytale. It’s called a Fairytale and that’s not supposed to leave any normal canvas or sculpture but rather should like a seed planted in those 1,001 Chinese, their emotions and heart, to move them to go to German Documenta on Castle. Documenta is kind of high-end elite type of Western culture practice, I would say it that way. If I go through Documenta, I’m very well-trained in art theory or practice, I would not even understand what they’re doing there. And it is completely foreign and against the human perceptions. So I said I’m not going to join Documenta to do the same thing. So I would invite 1,000 Chinese to take opportunity to make the two culture to meet.

I select those people from the internet. At that time, I already know how to use the internet. There could be farmers, could be women, minority women from some mountain remote area. The women never have a passport, and if they apply a passport, they have to make up their name because they are never had a name. They would only been called somebody’s wife or someone’s mom. So they made the passport, they take all the procedures, take photos, then get the passport. I successfully manage them to get a visa. Basically in today’s language, it can be like I performed more or less like a travel agent for these 1,000 Chinese have to buy insurance and tickets and ship them to Germany Castle.

That city, they may never even see a Chinese. So everybody look at those, “Oh, those are Chinese. Look at those. Ai Weiwei is Chinese.” So I become very well known. Newspapers start only talk about me because I made all that 150 artists are very jealous and they all hate me. That’s why I can never really be recognized by art world because I did something which is not normal. It’s not under their art history teacher’s practice. But I had a good time.

Peter Sellars: And 1,000 people had an amazing time and 1,000 hearts and 1,000 pairs of eyes.

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. That’s the only time in history 1,000 Chinese people like farmers come to see art show. Never happened before, never happened later. Now all those people, their children study like museum management or something like that, strange enough.

Peter Sellars: But it’s an art project that makes suddenly a bunch of things that were totally impossible not only possible, but happen. And for me that’s one of the most beautiful things in your work is not only something become possible, but you actually do it.

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. My life told me impossible things can happen and it happens all the time. Thank you. Thank you very much.

Orville Schell: Weiwei, do you miss China?

Ai Weiwei: That’s like a question, do I miss myself? I don’t miss myself.

Orville Schell: So you feel content and happy and productive in exile? It’s not a source of… You don’t feel deprived in some way.

Ai Weiwei: Well, of course we all have our sentiment or memories, some kind of nostalgia feelings, but still think about the planet is such a small dust in the universe and it comes as being miracle and it will go. It’s not going to be always like this. So then personal sentiment, it works, but also we have to have perspectives. I spent already 42 years in China and ended up like I’m a most unwelcome person. So I accept that kind of condition.

Orville Schell: And you don’t expect in your lifetime you’d go back?

Ai Weiwei: I can go back any time, actually. I have a Chinese passport. But I’m not sure I can come out again. Those were really just… I don’t know.

Orville Schell: Well, that can change your plans.

Ai Weiwei: It can be a one way trip. So I make sure not to buy the roundtrip tickets because it would be wasted.

Peter Sellars: This sense that you are connected now to a whole new generation of artists, one of the things that’s very beautiful about your work is it’s hardly ever the fingerprint of the artist on the work. But in fact, teams of people are creating these huge projects that you are imagining that cover entire cities and that have all of these layer after layer of element and process and people coming together to create things and imagine things. And so would you just talk about your staff and the young artists that surround you and that interaction that you have. Every one of your projects calls for a lot of people.

Ai Weiwei: I realize in my life I somehow always attracted somebody has some mental problems. I wouldn’t believe people working with me for 30 years. I always wondering, “Do you really want to still be here?” And the people still here. I am kind of shy to ask them why because life teach me not to ask deeper questions. But yeah, I realize people in general very hard to find a real society or real connection to another. Somehow because my mental problem attract similar type of people and I have compassion with those kind of people. But sometimes it get really crazy, really… Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Sellars: Because we don’t see that part, do we? The exhibit is usually relatively under control.

Ai Weiwei: You see that part. I think I told you I supposed to sitting on the park bench, but now I’m sitting here with you. This is pretty crazy. I never can imagine 1981. That’s 40 years ago. I was in Berkeley. That time I start to study English. My girlfriend has much better English training. Her first words she teach me is, “Excuse me.” I think that words is so difficult to pronounce. In China we would say [Chinese language], something like that, but “excuse me” when somebody walk towards you in supermarket or something. So she told me, “You can never really learn English. It’s not possible.” I also believe her. I gave up. But my English training started once so many interviews come. So I started to learn a little bit basic language.

Peter Sellars: One of the incredible skill points, of course, which is always this wuwei of by doing nothing, there’s nothing that cannot be done, and you use nothing really, really beautifully and really powerfully in your practice. But that nothing has… You’ve really touched an amazing fulcrum between having nothing and having everything. Your artworks involve a lot of money, big-time capitalist investment, very expensive locations, very expensive collectors, and total poverty and this living on the edge. Normally, those worlds don’t meet, of the person on the park bench and the billionaire class that we’re living with now. And in your work constantly, these two extremes are meeting.

Ai Weiwei: So…

Orville Schell: You’re a tough interview, Weiwei.

Ai Weiwei: I mean, what do you… Just let me know what you say.

Peter Sellars: For me, this is the future negotiation in America and in the planet. For me, it’s a new generation of art that you’re making for a new period where we’re living in these economics of extremes, massive inequality that goes beyond anything that ever existed on this planet before. Somehow, you’ve found a path that actually moves right into the heart of the crisis itself. I’m not speaking about China. I’m just speaking about the West and this situation that we’re living in here and now. In that sense, having done what you’ve done, how do you move forward?

Ai Weiwei: Well, I think very often we so much enlarged our vision because we look at ourself with no perspective. Also we can look at the nation with no perspective. Of course, if you look at Rome, like the history in the Western culture, it’s a unbelievably strong nation. And of course you look at Rome today or Italy, you only need to see spaghetti or Mamma Mia or those things. It’s not Rome anymore. Also in China in the history, there’s a lot of a great moment, great, how do you say, dynasties, but they all disappeared and every Chinese trying to get an American visa and to come to here.

So we have to be much relaxed to think there’s up and down in every nation or every power. As individual, there’s not much we can do, but we try to protect ourself, to have these words. You use integrity or something. But it’s still very hard. What is integrity? And normally we said, “OK, we’re trying to fight for social justice or some kind of fairness there. That’s how help us to understand ourself and others.” But even that is extremely difficult because it need a lot of effort. You need to take action. And who want to give this time of afternoon tea to go do something which… Fight is not a normal condition. It’s not a acceptable, in general, condition. So I don’t know. I think anything can happen and I don’t think we can really prevent those situation and, yeah, that’s how I feel.

Orville Schell: Maybe before we have a few questions from you all, I just can’t resist asking one more. What do you think of Xi Jinping?

Ai Weiwei: Well, he’s a man about three, four years older than me. I don’t know him. I look at the image. He’s quite healthy, and I’m so sure he’s going to stay there for very long, long before all your president. You last maybe eight years. But he will stay there at least twice as long. So there’s a very different perspective. He is thinking about now, no longer talk about American dream here, but he’s talking about Chinese dream. He thinks there’s one chance for China to achieve. They normally says this is a hundred years, like a opportunity only may come in a hundred years. So China is, I would believe, will become a stronger nation. They will create more conflicts with U.S. The U.S. was, is, still is very strong, but still how U.S. would deal with someone who have a clear vision as a competitor and also this is not going to disappear. China is not going to disappear. So I think I need a lot of political wisdom here.

Orville Schell: If you had to place a bet, would you bet that he would succeed in achieving his China dream or possibly fail?

Ai Weiwei: I don’t think he will fail because China is a failure. Already China has never really, besides made some money, and still lacking of clear fundamental values about to establish a society which is legally existing because now as an authoritarian state, it’s really managed by pressure, army, and police and all those things. So this never had a election, but that kind of situation can last forever and that doesn’t mean that society cannot succeed. So it’s very hard to compare with state capitalism, with this kind of classic capitalism. So I think state capitalism have a lot of advantage.

Orville Schell: OK. Now, I think there’s some microphones. I can’t see too clearly, but we could take maybe… We have about 15 minutes, if you would like to ask a question. Here’s a microphone coming out and one over here, possibly. Would you be brief if you want to ask a question, and we’ll try to get a few in. Right here. Come down to the microphone, please.

Audience 1: OK. Eenie, meenie, miney, mo. Is it your real mom in Never Sorry, or was that a fake mom? In your documentary Never Sorry, was that your real mom that you were talking with? I’m guessing no.

Ai Weiwei: In the film?

Audience 1: Yeah.

Ai Weiwei: That’s my mom.

Audience 1: Oh, because right before you brought her into the picture, you said, “Maybe I won’t bring my real mom and we’ll just tell everybody it’s my mom.” So I was always wondering if that really was her.

Ai Weiwei: Well, it certainly is not an artificial mom.

Orville Schell: But Weiwei, I must say you do have an infatuation with the word “fake.”

Ai Weiwei: Fake, yes.

Orville Schell: Yeah. So…

Ai Weiwei: OK. My company, I have to register company, so I register the English words, the fake… English words actually translate into Chinese that’s [Chinese language] but if you use Chinese spelling system, that become “a fake.” So it’s complicated.

Orville Schell: But not a fake mother in the film. OK.

Audience 1: Thank you.

Audience 2: I appreciated your work dealing with surveillance in China. I’m wondering if you have ever been surveilled by any other countries, and if you’ve ever looked into whether the U.S. has an FBI file on you.

Ai Weiwei: Well, yeah, because I was dealing with China, I was a bit naive, but very soon I realized U.S. even tried to listen to German chancellor’s private talk, so I’m sure U.S. does it better than anybody. And yeah.

Orville Schell: Next, please.

Audience 3: Hello. Thank you for your art and your activism. I recently was able to see the 12 Chinese zodiac heads up at a winery in Sonoma and that was incredible, and it made me wonder how do you balance being a champion of Chinese culture and at the same time a critic of the Chinese government?

Ai Weiwei: Yeah. I think that is the same quality.

Orville Schell: OK. Next. Right here.

Audience 4: In the U.S., there’s a lot of people that look at and consume art and contemporary art. It’s a strong overlap between political left. In China, not only is it left and right a little bit different, but also you can get disappeared for making art. I was wondering do you think that art is the same medium in China or if it has a different function?

Ai Weiwei: Compare Chinese art with Western art?

Audience 4: I guess, yeah. Art as a medium in the West versus China.

Ai Weiwei: Well, that’s very, very difficult though because China has basically a society have a strong censorship. It’s OK to have strong censorship. It’s like you building the roof. It’s very low, but still people can live in there and can have a meaningful practice. But in the West, you have have the roof like sky-high, but doesn’t mean you produce works. The work is not about, normally you say, “Oh, you have a freedom; you can do whatever you like.” But I think that’s wrong concept. I think nobody can say we have a freedom or of course even mostly artists cannot say that because the only freedom you may have is to find out that you don’t have that freedom. Otherwise, it’s irony. Yeah.

Orville Schell: Next.

Audience 5: Yeah. I’m struck by an hour-and-a-half of conversation about art and politics and the United States and China, and not a word yet about climate. So all of this about human rights and refugees and the reason why this will become a massive problem for everybody is climate.

Ai Weiwei: Can you make the mic a little bit? You can bend a mic.

Orville Schell: She’s asking about why haven’t we said anything about climate change.

Ai Weiwei: About what?

Orville Schell: Climate change.

Ai Weiwei: Oh, OK. I try to test if the people would ask that. I always failed because the people always ask that. I always think people talk we have to protect the environment or to climate change situation. I kind of cynical about it. I always say you don’t “protect” the environment; you just don’t ruin the environment. I think the society are trying to be politically correct where the one protects the environment; there’s the one ruining the environment, which is not true. We all ruin the environment. Even you pretend you are protected. I’m sure I can easily argue you did many senses really ruin the environment. Thank you.

Audience 5: My… Americans have a very, very different perspective on it.

Orville Schell: Next, please.

Audience 6: Thank you for who you are as much as for what you’ve done. When we talk about art and activism, I’ll generalize and say that both roles hold the tension of our culture and society and our world. And holding that tension is very draining. How to recover from that exhaustion, how do you hold that tension and keep holding it?

Ai Weiwei: Well, I don’t see there’s… For me, it’s a natural act. I don’t see art can be separated from so-called activism. I always say if art without activism, is that artist? So my tension is really trying to figure out my hotel room, how to switch the light, or how to really find out how the shower to turn. It’s very difficult. It’s extremely difficult. Life has been made difficult by those designers and the architects and yeah. Next.

Audience 7: Thank you for being you. I also grew up in China in my formative years and I came here to the States in the ’80s as well, and I worked in Harlem from 3:00 PM to 3:00 AM, so I understand exactly what you’re talking about. Nothing is when I experienced in China, the years of growing up where we had no books except for the officially sanctioned ones, then all of a sudden in the ’80s in my high school, the floodgate got lifted and we had all kinds of opportunity of reading the classics, of humanities, including a lot of your father’s poetry. That was very big in the ’80s. I read a lot of that.

So now I’m going to ask you a question very unpopular with this crowd, which is the schools here. What I see on campuses from kindergarten to colleges, a lot of the great classics are being displaced and substituted with something subpar in the name of political correctness. I, as someone who experienced China and here, I feel like I have a unique duty to educate the world about the minutia and the nuances, what it means to living under communism, under socialism. I just want to see what you might say to that.

Orville Schell: So she’s an immigrate classicist who believes in the classics and the value of the classics.

Audience 7: I’m a classic constitutional liberal as you can say. But anyway.

Orville Schell: How about you, Weiwei?

Audience 7: [Chinese language] But anyway…

Ai Weiwei: [Chinese language].

Audience 7: Oh, [Chinese language]. Anyway, [Chinese language]. Anyway.

Orville Schell: She’s asking about fundamental basic classical works, I think, in both cultures, but particularly here.

Audience 7: No, I’m just saying that when you look at their world right now that’s changed… Sorry for taking up time. What you look at the America that has kind of experiencing some of the censorship, some of the gatekeeping of what kids should read and not read, the kinds of things that I experienced when I was growing up. Yeah.

Orville Schell: Let me put the knife in here. She’s saying in America now there is a level of censorship, particularly a lot of universities, because of sort of “woke” culture. What’s your view?

Ai Weiwei: I feel in our education or mainstream, how do you say, propagandas or there’s a strong censorship in United States. Sometimes you can compare to Cultural Revolution in China. It’s not allowed different opinions and clashes. Our opinions can be obviously wrong, but have a perfect right to speak out. So I think to trying to clean up the society is a similarity with Nazism, to say we have to be absolutely right or to have this elite idea. I think that is more dangerous, to have a society more loose, to have wrong ideas or to different voices. So I think U.S. certainly have the ground to become a black/white society. You don’t have the gray area. So that, I think, is a potential danger to… It’s not healthy at all.

Audience 7: Thank you so much.

Orville Schell: Thank you.

Audience 7: Thank you.

Orville Schell: Now, we have time for one more question. We’ll take it from you.

Audience 8: Hi, my name is Trudy. I am a Tibetan refugee in exile, and I really am inspired by your work. My question to you is since we know that the human rights situation in both China and Tibet has been deteriorating… Even in recent years, there have been artists and writers being censored and put in prison, what do you think could be done in a place like Tibet, which is occupied land? What do you think could be ways to resist the colonial state? And do you think there’s any way that Tibet could be free from what is it right now?

Ai Weiwei: That’s really a very tough question, not only for Tibetan, but for many, many so-called minority people or people’s rights being horribly violated. I cannot really give advice. If you look in the world, you look at the map, so many people’s rights being violated in many, many locations and even for the people are fighting so strongly still will not change the situation. We see cases like that everywhere. So I don’t know. I cannot answer it. It’s just even encouraging people to fight, it doesn’t really bring a brighter future because people just being put in jail, sentenced, and very little attention being paid for those writers and the thinkers, and they can be lifetime in jail.

Orville Schell: Before we close out, I just want to deliver a quick commercial. Peter Sellars is going to be here with the Los Angeles Master Chorale on October 28th to present music to accompany a departure. I’m sure it’ll be wonderful, and encourage you all to come.

Peter Sellars: It’s a COVID ceremony for saying goodbye to people we couldn’t say goodbye to.

Orville Schell: Yeah. So Peter, I want to thank you. And Weiwei, thanks a million for being here. (Applause)

[Music: Silver Lanyard by Blue Dot Sessions]

Outro: Youve been listening to Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. Follow us wherever you listen to your podcasts. You can find all of our podcast episodes, with transcripts and photos, on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

Courtesy of Ai WeiWei

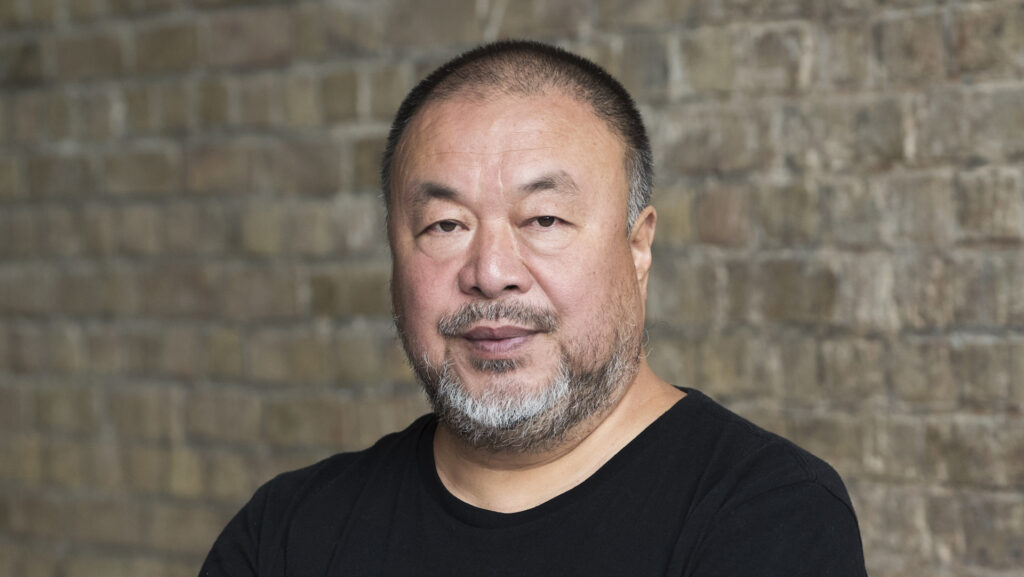

In Berkeley Talks episode 181, renowned artist and human rights activist Ai WeiWei discusses art, exile and politics in a conversation with noted theater director and UCLA professor Peter Sellars and Orville Schell, director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society and former dean of Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism.

Ai, who grew up in northwest China under harsh conditions because of his poet father’s exile, openly criticizes the Chinese government’s stance on democracy and human rights. He is well-known for his provocative works, including his 2014-15 installation on San Francisco Bay’s Alcatraz Island, @Large, that the LA Times called, “an always-poignant, often-powerful meditation on soul-deadening repressions of human thought and feeling.”

“Normally, people call me an artist or activist, and I am often forced into one condition,” he says. “It’s not that I intentionally try to create something or to crystallize something, but rather I’ve been put in extreme conditions, and I have to focus on dealing with those situations. Normally, I don’t accept the easy answer.

“So I think I have to find a language to illustrate my expression, and it comes out in certain ideas or materials. We can call it art. I don’t think my art really looks like art, but still, it’s hard to categorize it. I’m a bit ashamed about it because everything in real life, it has a purpose. It has clear problems and solutions. But the art is not really about that. It rather creates problems after problems. So yeah, that’s what I do.”

Listen to the full conversation in Berkeley Talks episode 181, “Chinese activist Ai WeiWei on art, exile and politics.”

This Sept. 24 event was co-presented by Cal Performances, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) and the Townsend Center for the Humanities.

Read about 10 of Ai WeiWei’s adventurous works on Cal Performances’ blog Beyond the Stage.