For new Berkeley professor, solving homelessness requires data, direction — and belief

Born in San Francisco and raised in the Bay Area, Jamie Chang's personal and academic journeys have pointed her toward the systemic causes of homelessness. Now a professor at UC Berkeley, she’s seeking solutions to California's most vexing puzzle.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

November 2, 2023

Jamie Chang has studied homelessness for two decades. She’s spent more time interviewing people in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district and examining the role of drugs, alcohol and government policies on city streets than almost any other scholar. Her personal experience with unhoused people dates back to her childhood.

Yet until recently, Chang, a new faculty member this fall at UC Berkeley, didn’t actively promote her research. For years, she worried she’d ruffle feathers in a hyper-politicized field rife with misinformation, short-sighted solutions and hot takes.

Then, she remembered what a close mentor had said about her duty as a social scientist: “It’s not fair for you to do this research with all these participants and not tell their story.”

“It was a shift in the way I think,” said Chang, an associate professor at the School of Social Welfare. “It’s not about me. I’m going to be one of many, many voices in this arena, but I need to represent the folks that I speak to.

“Because they took sacrifices and risks in telling me their story.”

I have this incredible platform, not just to understand for my own sake, but to be a resource and microphone advocating for people, too.

Jamie Chang, UC Berkeley professor

This semester, Chang is teaching courses on research methods and theory, as well as a doctoral seminar. All bridge the ideas of social work with on-the-ground realities. She’s also co-authoring what is believed to be the first nationwide study of deaths among unhoused people.

Chang’s goal is to help solve California’s most vexing and visible puzzle.

What’s needed, she said, is to force a more objective, solutions-oriented approach to homelessness among local, state and federal governments. It’s possible and necessary to change what she calls an “absolutely unacceptable social and moral failing.”

“When I started studying homelessness, it was purely out of curiosity and a desire to understand,” she says. “Now, I have this incredible platform, not just to understand for my own sake, but to be a resource and microphone advocating for people, too.”

Linda Burton, dean of Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare, called Chang’s hire “essential.” Chang joins other social welfare scholars at Berkeley who specialize in poverty and substance abuse, and she works closely with the campus’s homeless outreach coordinator.

“She brings a powerful innovative research and practice lens to our community for addressing the needs of the unhoused,” Burton said. “And, as a native daughter of the Bay Area, she is deeply committed to making a difference in the lives of the unhoused in her own backyard.”

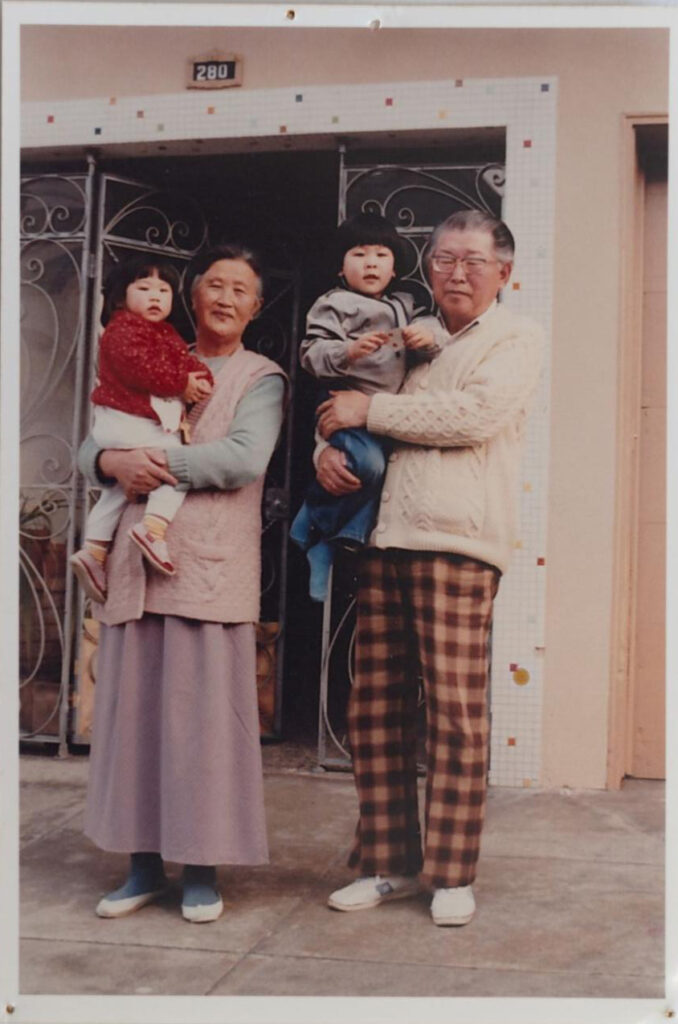

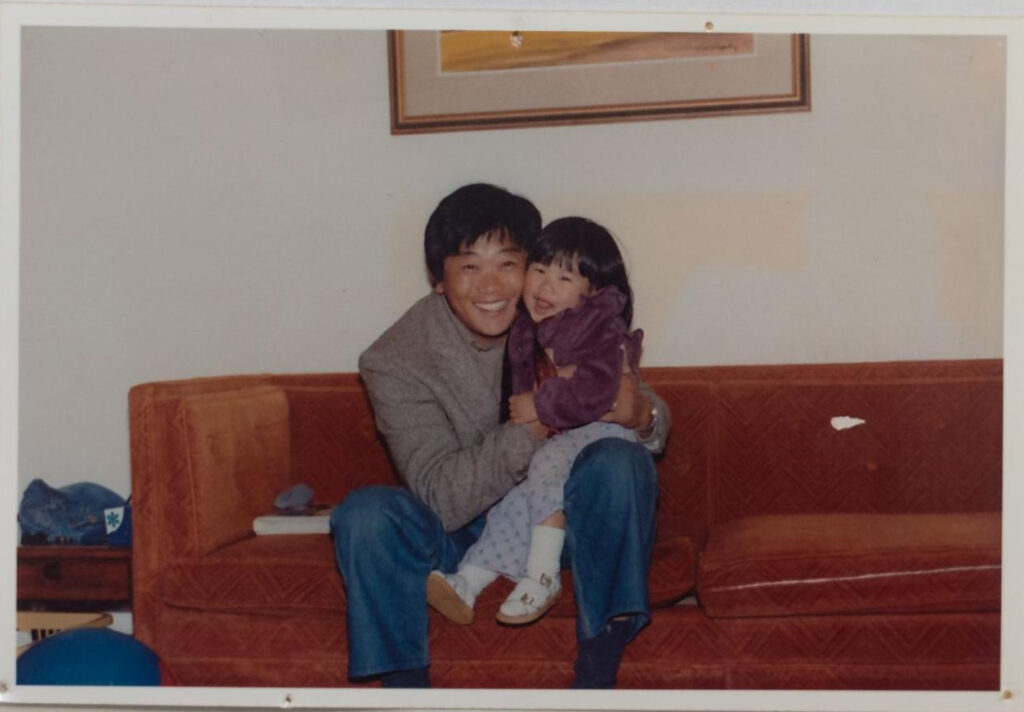

With SF roots, interest in homelessness runs deep

Chang’s father is from North Korea; his mother carried her children across the 38th parallel as the bridges from north to south collapsed. Chang’s mother hails from Busan; her father was a laborer in Japan when the Hiroshima bomb went off. He watched the explosion from the hills. It’s a history that Chang holds close.

Courtesy of Jamie Chang

“These are my roots, people who sacrificed everything to survive, to be free,” she said. “I feel an enormous responsibility to use my voice effectively, and for people being harmed.”

Born in San Francisco, Chang remembers homelessness as part of daily life. She saw it when she rode with her father during work trips for the family’s house painting business. In the 90’s, she read San Francisco Chronicle stories about crises in the nearby Tenderloin.

In high school, Chang volunteered at homeless kitchens and shelters, curious about her unhoused neighbors and wanting to know more about them and their challenges. Her parents worked around the clock to keep the family of six — plus occasional grandparents — afloat.

At that young age, Chang began to perceive how individual failings failed to explain the vast scope of homelessness in San Francisco. She soon discovered how mental illness, mixed with a fragmented health care system, causes lives to unravel.

“Over the years, I’ve seen numerous people — friends, neighbors, relatives, co-workers — become homeless,” Chang said. “These are normal, good, everyday people who either developed health issues or encountered a serious life event that spun out of control.

As a youngster, Chang watched a relative and one-time family role model who briefly attended UC Berkeley cycle in and out of poverty and state institutions after he developed schizophrenia. Members of the church she attended struggled with poverty and homelessness. Just last month, she got the news that a friend was sleeping on cardboard spread on a sidewalk, enmeshed in mental health struggles.

She said she’s witnessed how systemic forces shape the negative narrative about those we know who become homeless.

“I don’t think homeless people should be othered so much,” she said.

As an undergraduate at UC San Diego, Chang majored in journalism and political science. She had long admired Connie Chung, the legendary news anchor and reporter among the few Asian American women in high-profile, visible careers. She relished the chance to hear and tell people’s stories.

But when she graduated in 2002, she said she felt “lost,” unsure she wanted to be a journalist. It was also a period of debt and instability. Memories of her family’s financial struggles during her childhood played on repeat in her mind. Panic was setting in.

After applying for dozens of jobs, she accepted the first one she was offered — an administrative assistant position at UCSF scheduling doctor visits and MRI appointments. It was a far cry from journalism, but it was something.

There, she began to consider becoming a scientist. Dr. Soonmee Cha, a UCSF neuroradiologist, offered Chang a research position in a brain tumor research lab, a decent-paying job with benefits that Chang kept for six years.

But her thoughts kept going back to the people she’d met who struggled with poverty and housing instability. She needed a career that was more in touch with her roots. Interactive. On the ground, where the stories were.

“I needed to study homelessness.”

Starting her research in the Tenderloin

Chang took night classes for her master’s degree in political science at San Francisco State University. She explored how the stigma around homelessness affected local voting behavior.

The work was stirring and prompted Chang’s doctoral work at UCSF in medical sociology, which combined her interest in health care and disease with her passion for in-depth storytelling. She drilled into a timely issue: What should treatment look like for people who are homeless and struggling with addiction in impoverished neighborhoods? How can society expect these individuals to recover in a drug-saturated, stressful environment?

It is such a politicized space. They don’t teach you how to navigate that in school.

Jamie Chang

Much like museum docents who lead visitors to critical sites, Chang asked several unhoused people in the Tenderloin to show her spaces of significance to them — shelters where they slept, streets where they walked and substance-use treatment programs they joined. They also showed her safe spaces — or the lack thereof — for them to simply be.

“One of the things that was apparent to me was just how very stuck people are, even on the streets people walk on,” Chang said. “And some folks felt so unsafe that they literally never left their tiny hotel room.”

On these walks, in the back of her mind was the possibility of seeing some of her loved ones lost to homelessness, having heard that they were around the Tenderloin.

“I would be looking for their faces,” she said. But she never saw them.

When she completed her dissertation in 2013, Chang was among the most knowledgeable scholars nationwide on the systemic problems affecting the health of people on the streets — too few good treatment options and too much resistance to long-term solutions for poverty and housing insecurity.

But she feared entering conversations as an expert.

“It was terrifying because of imposter syndrome and insecurity about not knowing everything, but also because it is such a politicized space,” she said. “They don’t teach you how to navigate that in school.”

Silicon Valley sweeps with fatal consequences

In 2017, Chang became an assistant professor at Santa Clara University. She immediately noticed a void in the academic research on Silicon Valley homelessness, so she formed the Unhoused Initiative and met with the county’s coroner. In the years that followed, Chang and her colleagues — including several students — mined hundreds of investigations into the deaths of homeless people and conducted scores of interviews to learn what preceded their deaths.

They found that, since 2011, more than 1,700 people had died on the streets of Santa Clara County. Critically, they found that homeless encampment sweeps by local authorities were destabilizing people on the streets — sometimes with fatal consequences.

Besides destroying people’s belongings, including medications and records, sweeps effectively forced people to more dangerous places, like riverbanks or train tracks, where it’s more difficult to access services and get emergency help.

She and her colleagues presented their work to national groups and issued public statements. Soon, journalists were calling from across the country to interview her about the government’s role in preventing such deaths.

In a profile of her team’s work, Chang remembered the advice from her UCSF mentor, Janet Shim. And she didn’t hold back in her public comments.

“Looking around our very own communities, I am sickened that we have constructed a society that lets people suffer, languish, and die in extreme poverty,” she was quoted saying. “It’s wrong — it’s that simple. All of us are the architects of this injustice unless we actively work to counter it.”

‘I just want to believe things can be better’

The challenge of implementing grand, systemic solutions to homelessness can seem overwhelming, she admitted. But there are reasons to be optimistic.

For example, as devastating as the COVID-19 pandemic was, it showed there can be rapid, large-scale solutions to society’s most significant challenges. Likewise, California’s effort to move thousands of people from the streets to hotels while providing them with resources to find longer-term stability — while far from perfect — has shown some signs of success.

That kind of out-of-the-box thinking is what Chang said is needed to fix what many see as an intractable problem. To be sure, NIMBYism, where communities protest homeless people, as well as housing and financial remedies intended to help them, hinders that effort. Fragmented state and federal responses don’t make it easy, either.

But, as she reminds her students, effective policy solutions start with quality research.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

At Berkeley, Chang’s office on the third floor of Haviland Hall is spare, mostly empty — save for her desk, table and a few personal effects on the shelf. A single poster of a UFO hovering above a forest and the bright white letters on the bottom: “I WANT TO BELIEVE” is pinned to the wall, a replica of one above the desk of FBI Special Agent Fox Mulder in The X-Files.

Chang has always loved the alien-chasing show that each week asked viewers to consider the possibilities — of aliens, opportunities and unknowns. Skeptical, yet cautious, optimism of our ability to know whether aliens exist is a tenet of the show.

The poster’s message resonates with how Chang feels about her work on homelessness.

“I just want to believe things can be better,” Chang said. “I want to believe that there’s something out there that’s better. I just want to believe that it’s going to be OK.”