They built the railroad. But they were left out of the American story.

On Nov. 17, Cal Performances is presenting American Railroad by Silkroad Ensemble. It's one of several notable works in recent years that explores the lives of the immigrants who built the U.S. transcontinental railroad.

November 13, 2023

Follow Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast about the people and research that make UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is. Review us on Apple Podcasts.

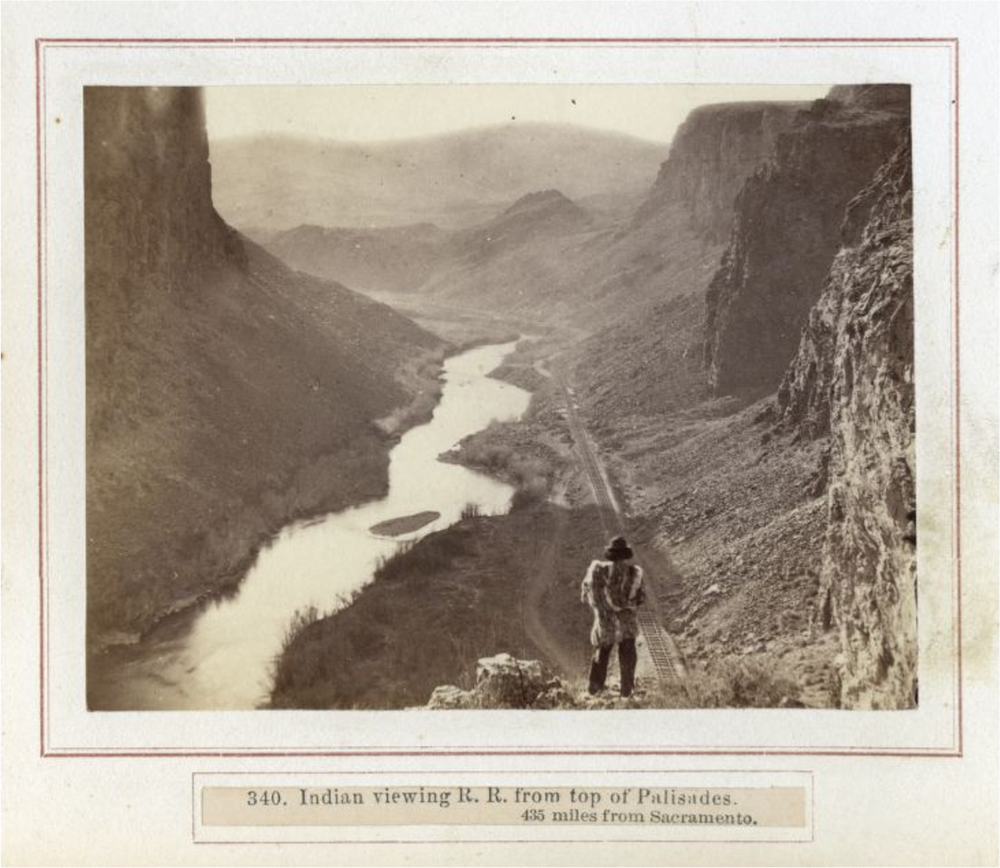

The U.S. transcontinental railroad is considered one of the biggest accomplishments in American history. Completed in 1869, it was the first railroad to connect the East to the West. It cut months off trips across the country and opened up Western trade of goods and ideas throughout the U.S.

But building the railroad was treacherous, brutal work. And the companies leading the railroad project had a hard time retaining American workers. So they began to recruit newly arrived immigrants for the job, mainly Chinese and Irish.

And these immigrants, who risked their lives to construct the railroad, have largely been left out of the story.

In recent years, though, there has been a new emphasis on reframing the narrative to include the perspectives, contributions and struggles of railroad workers, not only in scholarship, but in the arts.

On Nov. 17, Cal Performances is presenting American Railroad by Silkroad Ensemble. It’s one of several notable works in recent years that explores the lives of the immigrants who built the U.S. transcontinental railroad.

Anne Brice (narration): This is Berkeley Voices. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: “Ultima Thule” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice (narration): The U.S. transcontinental railroad is considered one of the biggest accomplishments in American history. Completed in 1869, it was the first railroad to connect the East to the West. It cut months off trips across the country and opened up Western trade of goods and ideas throughout the U.S.

But building the railroad was treacherous, brutal work. And the companies leading the railroad project had a hard time retaining American workers. So they began to recruit newly arrived immigrants for the job, mainly Chinese and Irish.

Until recent years, these immigrants who risked their lives to construct the railroad have largely been left out of the story.

Hidetaka Hirota: Overall, immigrants did the most difficult jobs for the development of America’s infrastructure.

[Music fades]

Anne Brice (narration): Hidetaka Hirota is an associate professor of history at UC Berkeley. His major area of research is 19th century U.S. immigration history.

Hidetaka Hirota: If you worked in railroad construction, accidental falls of rocks, avalanches of snow, those things were always there. This is the age of cutthroat capitalist competition, and this is before the age of governmental regulation of labor conditions. So little protection was provided, little concern was there, for immigrants’ welfare, workers’ rights. Those things did not really exist.

Anne Brice (narration): Construction for the transcontinental railroad began in 1862. The two competing companies awarded the project — Central Pacific in California and Union Pacific in Nebraska — built eastward and westward to meet in the middle. Each company’s labor force was based on location and connections.

In Nebraska, workers were mostly Irish immigrants, Civil War veterans and African Americans, many of whom were enslaved until the end of the war in 1865. And in California, the Chinese made up a majority of the laborers. At its peak, about 90% of the railroad workforce was Chinese.

Immigrant workers were aggressively recruited in all sorts of ways. Some Chinese and other groups had already come to California during the Gold Rush in the 1850s. Some were approached by agents when they first arrived at ports or boarding houses. And toward the end of the project, many were recruited from their home countries.

[Music: “Eggs and Powder” by Blue Dot Sessions]

But while the U.S. wanted these foreigners for their labor, the workers, especially the Chinese, were met with open hostility by American society.

Hidetaka Hirota: Railroad companies obviously valued Chinese labor because it was cheaper than white labor. So in this sense, Chinese were quote-unquote welcomed. But then, the other side was this growing anti-Chinese hostility.

California Gov. John Bigler famously publicly accused the Chinese of stealing Americans’ wealth. Bigler characterized the Chinese as thieves, outsiders to the United States, and an inferior race that disturbed the peace and tranquility of California. “Peace” and “tranquility” were his original words.

Opponents of immigration criticized foreign workers for allegedly lowering the wage standards, and as a result, threatening Americans’ employment and, ultimately, American democracy. And obviously, this is not simply an economic argument because racism and ethnic prejudice often aggravated these views.

But at the same time, the industrial, commercial and economic development of the United States created insatiable, unlimited demand for immigrant labor. And as a result, this reality really made immigration restriction unpopular policy for capitalists and business owners.

[Music fades]

Anne Brice (narration): Although a lot is known about how the transcontinental railroad was constructed and its role in Westward expansion, says Hirota, very little is known about the everyday lives of the laborers who made the railroad possible.

Hidetaka Hirota: There is a logistical problem in citing the subject. In general, historical sources, documents on immigrant workers are very limited. You can definitely get access to records of railroad companies that employed immigrant workers, but when it comes to the materials produced by the immigrants themselves, that information is limited, sadly. We’re not talking about the kinds of immigrants who constantly wrote in diaries about everything in their lives.

Anne Brice (narration): In recent years, though, there has been a new emphasis on reframing the narrative to include the perspectives, contributions and struggles of railroad workers, not only in scholarship, but in the arts.

Stanford University’s Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project recovered Chinese railroad worker history with the help of hundreds of scholars, students and volunteers from around the world.

Alexander Craghead, a Berkeley professor of American studies and one of the nation’s preeminent railroad scholars, co-edited the 2022 book Continuity & Change: The Lure of North American Railroads, which “explores the photography of contemporary railroading in North America and the passage of time.”

And on Friday, Nov. 17, UC Berkeley’s Cal Performances is presenting American Railroad by Silkroad Ensemble. It’s part of Cal Performances’ programming for the series Illuminations: Individual and Community for the 2023-24 season.

[Music: “Far Down Far” by Silkroad Ensemble]

The performance tells the stories of the many communities who built the transcontinental railroad by weaving together elements of their music and culture of the time and throughout history.

[Music fades]

Kaoru Watanabe: My name is Kaoru Watanabe. I first started working with Silkroad Ensemble off and on around 2008. My instruments are the Japanese drums and the Japanese flutes.

Anne Brice (narration): The Grammy Award-winning Silkroad Ensemble was created in the late 1990s by cellist Yo-Yo Ma to bring together musicians from all over the world, bridging Asia, Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Kaoru Watanabe: The idea was even though people had different languages and traditions, musical styles, concepts of rhythm and melody and tuning, these musicians can work together, creating new harmonies and new vocabularies in which to have conversations, musical conversations.

Anne Brice (narration): Their current project, American Railroad, was conceived by artistic director Rhiannon Giddens, who joined the ensemble in 2020. Giddens is a celebrated vocalist, banjoist and fiddle player; a Pulitzer Prize winner and two-time Grammy winner; and a MacArthur Fellow.

Kaoru Watanabe: The idea is to tell the history of America, of how we went from pre-Europeans coming over and Indigenous people being here. And then, how this influx of immigrants from all over the world and enslaved people being brought in and how that changed the landscape, both the actual (landscape), but also the emotional and cultural landscape of America. And how many people have benefited greatly from the advent of the American railroad, but how many people, their lives were completely destroyed, whole communities and whole peoples were destroyed, their livelihoods and their lives taken from them.

So it’s a sort of celebration of how the world shifted and a celebration of the people who sacrificed, whether on their own terms or who were made to sacrifice, in order for us to be where we are today.

[Music: “Far Down Far” by Silkroad Ensemble]

Anne Brice (narration): For the project, Silkroad Ensemble members traveled around the country and spoke with scholars, historians and musicologists, as well as musicians and composers, to learn the stories of the people whose lives were shaped, often in heartbreaking ways, in the name of American progress.

[Music fades]

From there, ensemble members and outside composers created new songs inspired by the narratives and history and music of the time, while also infusing the songs with their own experiences and esthetics.

Kaoru Watanabe: As an artist, as a musician, I try to put my mind and my body into those states and try to imagine what those experiences were like.

When I was in Bennington, Arkansas, we did a project, we were speaking with a local historian there, and she was telling us about what are called hobo signs. They’re these signs that migrant workers, when they were jumping on and off of trains, would scratch into the back of another sign or on the side of a wall of a building.

And these signs were visible from the train and would tell other folks a message — and the message could be “Beware of dog,” or “Danger: Do not get off the train,” or “There is work and food available here,” or “There’s medical care available here.” You know, these simple circles and lines and dots and jagged lines. Simple messages, but they would be messages given from one to another. So when we were down there, we did a song where we improvised off of these signs.

And so we went through, like, three or four signs. And the first sign was “Beware of dog.” And so we did an improvisation of “Beware of dog.” And we played with the audience, and we had the audience look and try to, you know, interpret it in their own way. And we talked about what the signs meant and who was doing it and when that was happening.

And so the idea of, again, looking at these artifacts and hearing these narratives and interpreting them in our own way has been a really exciting process.

Anne Brice (narration): Watanabe, who went to a conservatory for Black American jazz and whose parents are Western classical musicians from Japan, says that within each musician in Silkroad Ensemble, there are so many different musical backgrounds and cultures percolating and brewing together.

Kaoru Watanabe: Whether it’s a Chinese pipa player or a banjo player from North Carolina or a … in the ensemble, we have Lebanese oud players, we have balafon players from Ghana. So we have musicians from all over the world. And stylistically, you’ll hear elements of music from all around the world.

The idea of voice, both literal and metaphorical, is very important to Silkroad Ensemble.

[Music: “Tamping” by Silkroad Ensemble]

The voice of the instruments, the voice of the singers in the group. And so how these voices can come together in harmony without having their own essences diminished. So we’re celebrating the essence of each individual voice, while coming together.

[Music fades]

Anne Brice (narration): After the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the Chinese and others who worked on the railroad stayed in the U.S. They continued to work on the rails, building more networks and maintaining existing rails, and they entered other sectors, like manufacturing and agriculture. Their populations grew, and they became part of American society.

Hirota says that the experiences of Chinese railroad workers have shaped the way we discuss immigration today, including undocumented immigration, immigration reform and perception of immigrants. And this tension — this American dilemma of wanting the cheap labor of immigrants, but not wanting them to make the U.S. their home — remains a contentious issue.

The contributions of the Chinese and other immigrant communities to the U.S., says Hirota, are immense. And he feels obligated to teach this history to his students.

I’m Anne Brice, and this is Berkeley Voices.

Professors Craghead and Hirota will participate with other Berkeley faculty members in a pre-performance panel discussion, “Memory, Identity and Pastness: Considering the American Railroad.” The talk will be on Friday, Nov. 17, at 6:30 p.m. at the Bear’s Lair on campus. It’s free and open to the public; no tickets or reservations are required.

To learn more about Silkroad Ensemble’s American Railroad, and to see related events, visit Cal Performances’ website at calperformances.org. There, you can also read more about the history of U.S. transcontinental railroad on its blog, Beyond the Stage.

Berkeley Voices is a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs at UC Berkeley. You can follow us wherever you get your podcasts. We also have another show, Berkeley Talks, which features lectures and conversations at Berkeley. You can find all of our podcast episodes with transcripts and photos on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

[Music: “Far Down Far” by Silkroad Ensemble]

Read a written version of the podcast episode:

The U.S. transcontinental railroad is considered one of the biggest accomplishments in American history. Completed in 1869, it was the first railroad to connect the East to the West. It cut months off trips across the country and opened up Western trade of goods and ideas throughout the U.S.

But building the railroad was treacherous, brutal work. And the companies leading the railroad project had a hard time retaining American workers. So they began to recruit newly arrived immigrants for the job, mainly Chinese and Irish.

Until recent years, these immigrants who risked their lives to construct the railroad have largely been left out of the story.

“Overall, immigrants did the most difficult jobs for the development of America’s infrastructure,” said Hidetaka Hirota, an associate professor of history at UC Berkeley. His major area of research is 19th century U.S. immigration history.

Courtesy of Hidetaka Hirota

“If you worked in railroad construction, accidental falls of rocks, avalanches of snow, those things were always there,” Hirota said. “This is the age of cutthroat capitalist competition, and this is before the age of governmental regulation of labor conditions. So little protection was provided, little concern was there, for immigrants’ welfare, workers’ rights. Those things did not really exist.”

Construction for the transcontinental railroad began in 1862. The two competing companies awarded the project — Central Pacific in California and Union Pacific in Nebraska — built eastward and westward to meet in the middle. Each company’s labor force was based on location and connections.

In Nebraska, workers were mostly Irish immigrants, Civil War veterans and African Americans, many of whom were enslaved until the end of the war in 1865. And in California, the Chinese made up a majority of the laborers. At its peak, about 90% of the railroad workforce was Chinese.

Immigrant workers were aggressively recruited in all sorts of ways. Some Chinese and other groups had already come to California during the Gold Rush in the 1850s. Some were approached by agents when they first arrived at ports or boarding houses. And toward the end of the project, many were recruited from their home countries.

But while the U.S. wanted these foreigners for their labor, the workers, especially the Chinese, were met with open hostility by American society.

“Railroad companies obviously valued Chinese labor because it was cheaper than white labor,” said Hirota. “So in this sense, Chinese were quote-unquote welcomed. But then, the other side was this growing anti-Chinese hostility.

“California Gov. John Bigler famously publicly accused the Chinese of stealing Americans’ wealth. Bigler characterized the Chinese as thieves, outsiders to the United States, and an inferior race that disturbed the peace and tranquility of California. “Peace” and “tranquility” were his original words.”

In one of Professor Hirota’s current book projects, The American Dilemma, he writes about the tension of American nativism against foreigners and the demand for their labor.

“One of the most consistent lines of anti-immigrant sentiment or argument in the U.S. was the critique of immigrant labor,” he said.

“Opponents of immigration criticized foreign workers for allegedly lowering the wage standards, and as a result, threatening Americans’ employment and, ultimately, American democracy. And obviously, this is not simply an economic argument because racism and ethnic prejudice often aggravated these views.

“But at the same time, the industrial, commercial and economic development of the United States created insatiable, unlimited demand for immigrant labor. And as a result, this reality really made immigration restriction unpopular policy for capitalists and business owners.”

Although a lot is known about how the transcontinental railroad was constructed and its role in Westward expansion, said Hirota, very little is known about the everyday lives of the laborers who made the railroad possible.

“There is a logistical problem in citing the subject,” he said. “In general, historical sources, documents on immigrant workers are very limited. You can definitely get access to records of railroad companies that employed immigrant workers, but when it comes to the materials produced by the immigrants themselves, that information is limited, sadly. We’re not talking about the kinds of immigrants who constantly wrote in diaries about everything in their lives.”

In recent years, though, there has been a new emphasis on reframing the narrative to include the perspectives, contributions and struggles of railroad workers, not only in scholarship, but in the arts.

Stanford University’s Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project recovered Chinese railroad worker history with the help of hundreds of scholars, students and volunteers from around the world.

Alexander Craghead, a Berkeley professor of American studies and one of the nation’s preeminent railroad scholars, co-edited the 2022 book Continuity & Change: The Lure of North American Railroads, which “explores the photography of contemporary railroading in North America and the passage of time.”

And on Friday, Nov. 17, UC Berkeley’s Cal Performances is presenting American Railroad by Silkroad Ensemble. It’s part of Cal Performances’ programming for the series Illuminations: Individual and Community for the 2023-24 season.

The performance tells the stories of the many communities who built the transcontinental railroad by weaving together elements of their music and culture of the time and throughout history.

Adam Gurczak

The Grammy Award-winning Silkroad Ensemble was created in the late 1990s by cellist Yo-Yo Ma to bring together musicians from all over the world, bridging Asia, Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

Kaoru Watanabe first started working with Silkroad Ensemble off and on around 2008. His instruments are the Japanese drums and the Japanese flutes.

“The idea was, even though people had different languages and traditions, musical styles, concepts of rhythm and melody and tuning, these musicians can work together, creating new harmonies and new vocabularies in which to have conversations, musical conversations,” Watanabe said.

Their current project, American Railroad, was conceived by artistic director Rhiannon Giddens, who joined the ensemble in 2020. Giddens is a celebrated vocalist, banjoist and fiddle player; a Pulitzer Prize winner and two-time Grammy winner; and a MacArthur Fellow.

Ebru Yildiz

For the project, Silkroad Ensemble members traveled around the country and spoke with scholars, historians and musicologists, as well as musicians and composers, to learn the stories of the people whose lives were shaped, often in heartbreaking ways, in the name of American progress.

From there, ensemble members and outside composers created new songs inspired by the narratives and history and music of the time, while also infusing the songs with their own experiences and esthetics.

“As an artist, as a musician, I try to put my mind and my body into those states and try to imagine what those experiences were like,” said Watanabe.

“When I was in Bennington, Arkansas, we did a project, we were speaking with a local historian there, and she was telling us about what are called hobo signs. They’re these signs that migrant workers, when they were jumping on and off of trains, would scratch into the back of another sign or on the side of a wall of a building.

“And these signs were visible from the train and would tell other folks a message — and the message could be ‘Beware of dog,’ or ‘Danger: Do not get off the train,’ or ‘There is work and food available here,’ or ‘There’s medical care available here.’ You know, these simple circles and lines and dots and jagged lines. Simple messages, but they would be messages given from one to another. So when we were down there, we did a song where we improvised off of these signs.

Max Whittaker

“And so we went through, like, three or four signs. And the first sign was ‘Beware of dog.’ And so we did an improvisation of ‘Beware of dog.’ And we played with the audience, and we had the audience look and try to, you know, interpret it in their own way. And we talked about what the signs meant and who was doing it and when that was happening.

“And so the idea of, again, looking at these artifacts and hearing these narratives and interpreting them in our own way has been a really exciting process.”

Watanabe, who went to a conservatory for Black American jazz and whose parents are Western classical musicians from Japan, said that within each musician in Silkroad Ensemble, there are so many different musical backgrounds and cultures percolating and brewing together.

“Whether it’s a Chinese pipa player or a banjo player from North Carolina in the ensemble,” he said. “We have Lebanese oud players, we have balafon players from Ghana. So we have musicians from all over the world. And stylistically, you’ll hear elements of music from all around the world.

“The idea of voice, both literal and metaphorical, is very important to Silkroad Ensemble.

“The voice of the instruments, the voice of the singers in the group. And so how these voices can come together in harmony without having their own essences diminished. So we’re celebrating the essence of each individual voice, while coming together.”

Thatcher Keats

After the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the Chinese and others who worked on the railroad stayed in the U.S. They continued to work on the rails, building more networks and maintaining existing rails, and they entered other sectors, like manufacturing and agriculture. Their populations grew, and they became part of American society.

Hirota said that the experiences of Chinese railroad workers have shaped the way we discuss immigration today, including undocumented immigration, immigration reform and perception of immigrants. And this tension — this American dilemma of wanting the cheap labor of immigrants, but not wanting them to make the U.S. their home — remains a contentious issue.

The contributions of the Chinese and other immigrant communities to the U.S., said Hirota, are immense. And he feels obligated to teach this history to his students.

Professors Craghead and Hirota will participate with other Berkeley faculty members in a pre-performance panel discussion, “Memory, Identity and Pastness: Considering the American Railroad.” The talk will be on Friday, Nov. 17, at 6:30 p.m. at the Bear’s Lair on campus. It’s free and open to the public; no tickets or reservations are required.

To learn more about Silkroad Ensemble’s American Railroad, and to see related events, visit Cal Performances’ website at calperformances.org. There, you can also read more about the history of U.S. transcontinental railroad on its blog, Beyond the Stage.