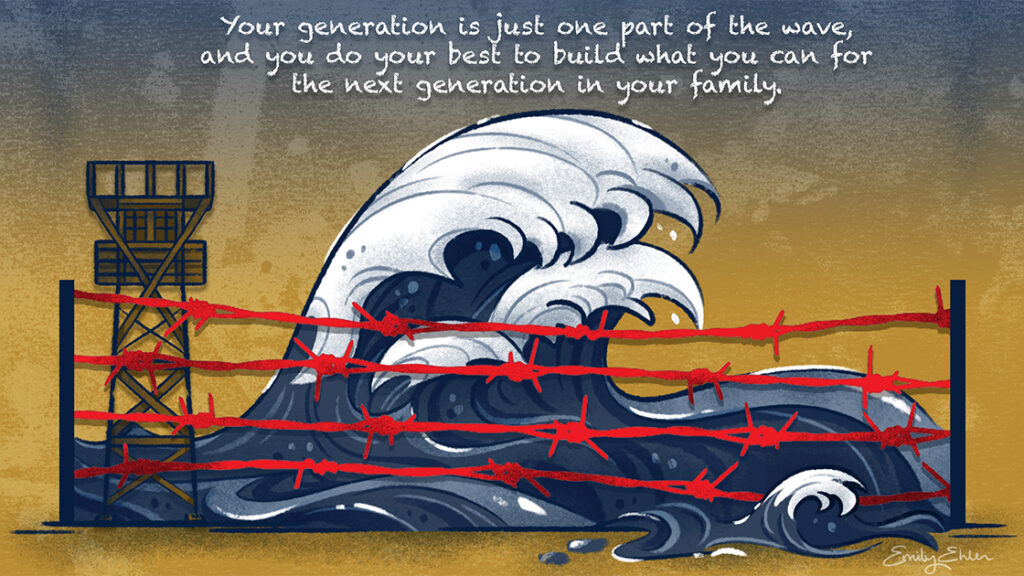

New podcast series explores the legacy of Japanese American incarceration

Season eight of the Oral History Center's Berkeley Remix podcast was created from 100 hours of interviews with 23 descendants of Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II.

December 14, 2023

See all episodes of Berkeley Remix season eight, “From Generation to Generation.”

See all Berkeley Voices episodes.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity protesters: “Close the camps! Close the camps!”]

Nancy Ukai: What we decided was: what are we going to do with all these cranes? Let’s go to Washington, D.C. Trump was in power. Let’s go to the fence and hang 125,000 paper cranes on the White House fence to symbolize the 125,000 Japanese Americans, Japanese Latin Americans, and Aleuts and everybody who got incarcerated, hang them on the fence and protest the detaining of immigrants.

Devin Katayama: That was Nancy Ukai, who’s a Sansei, or third generation Japanese American. During World War II, the United States government incarcerated her family in a prison camp at Topaz, which is located in Utah. Her family was incarcerated because of her Japanese ancestry. Now, Nancy is a member of Tsuru for Solidarity.

Nancy Ukai: We were organizing for this massive national pilgrimage against detention in February of 2020.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity protesters: “And we’re here today to say, ‘This must stop now!’”]

Devin Katayama: Nancy remembers when another member of Tsuru for Solidarity started organizing another protest.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity protesters: sounds fade out.]

Nancy Ukai: “Fort Sill, Oklahoma: the government now wants to use that as a place to detain children, and that’s where 700 of our ancestors, of our Issei immigrants, were held during World War II. Let’s go,” like in a week. It was just amazing. And, and that’s kind of when Tsuru for Solidarity, I think, really took off.

Devin Katayama: Tsuru for Solidarity was formed in 2019 after the Trump administration announced its immigration family separation policy at the US-Mexico border. This was the so-called Zero Tolerance Policy. Together, a group of Japanese American and Japanese Latin American survivors and descendants of World War II incarceration camps convened in Crystal City, Texas. They were there to protest the separation of children from their parents. Tsuru means “crane” in Japanese and symbolizes peace, compassion, hope, and healing.

[Theme song comes in]

Devin Katayama: At that Crystal City protest, they brought 30,000 of these brightly colored origami cranes with them.

Welcome to The Berkeley Remix, a podcast from the Oral History Center at the University of California, Berkeley. The Center was founded in 1953 and records and preserves the history of California, the nation, and our interconnected world. You’re listening to our eighth season, “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration.” I’m your host, Devin Katayama.

This season on The Berkeley Remix, we’re highlighting interviews from the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project. The OHC team interviewed twenty-three survivors and descendants of World War II-era sites of incarceration at Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. In this four-part series, you’ll hear clips from these interviews, which were recorded remotely via Zoom. These life history interviews explore identity, community, creative expression, and the stories family members passed down about how incarceration shaped their lives.

As a heads up, generational names for Japanese Americans are going to be important in this series. Issei refers to the first generation of Japanese immigrants to the United States. Nisei are the second generation, Sansei the third, Yonsei the fourth, and Gosei the fifth. Just think about counting to five in Japanese: ichi, ni, san, shi, go.

This is episode 1, “‘It’s Happening Now’: Japanese American Activism.”

[Theme song fades out]

Devin Katayama: Ruth Sasaki is a Sansei descendant of Topaz. She’s also involved with Tsuru for Solidarity.

Ruth Sasaki: Tsuru worked really fast, because they only heard about the impending incarceration of something like 1,500 kids at Fort Sill about ten days before the actual demonstration. And about twenty-six of us flew out to Oklahoma. We had like six survivors from various camps.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity drumming fades in]

Devin Katayama: On June 22, 2019, Tsuru for Solidarity activists gathered at Fort Sill to protest the planned detention of 1,400 immigrant children. The site of this federal detention center struck a nerve—Fort Sill had been a prison camp for 700 Japanese immigrants in 1942, and even before that, in 1894, 400 Chiricahua Apache prisoners. Activists like Ruth wanted to do everything they could to keep history from repeating itself.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity drumming sounds fade into Buddhist chants, clapping, bells]

Ruth Sasaki: All they wanted to do was to just share their story and explain why they were there. And of course, the MPs [Military Police] were trying to make us move and they were threatening us. And I was thinking, That’s not a good visual, you know, arresting these little, old ladies [laughs] who are obviously not violent. Everybody risked arrest because we didn’t know if we were going to get thrown into jail. And we were joined by 2 or 300 allies from all different groups: the Native American community, the Latino community, Black Lives Matter. There were Holocaust survivors.

[Natural sound: Bells fade out]

Devin Katayama: These protests took place all over the country, including close to Ruth’s home in the San Francisco Bay Area.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: In fact, she was part of a protest at Lake Merritt in Oakland, California, on March 6, 2021. Ruth was joined by more than 1,000 other people, some of whom objected to this family separation policy based on their own family history of incarceration. Like in Fort Sill, the protest movement wasn’t limited to just Japanese Americans—it brought together people from all kinds of backgrounds.

Ruth Sasaki: There was a, a big protest there, and that’s the one where we dressed up as World War II Japanese Americans. And we got a lot of press from that. I had created a little cage using a Target wire storage bin [laughs] that looked like a cage with little dolls inside like children. One was lying down covered by aluminum foil. I wanted a sign that would like be visceral, not just, “Stop incarcerating kids.” There was also a sign that said something like, “My family spent 3.5 years in a camp. [laughs] It wasn’t a summer camp.”

[nstrumental music fades out]

Nancy Ukai: There was a national day of opposition to the Zero Tolerance Policy, and it was “Keep Families Together,” and it was going to be a national day of solidarity.

Devin Katayama: This is Nancy Ukai again talking about Tsuru and a protest she went to at Tule Lake in Northern California—it’s another place where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity protesters, “No hate, no fear, immigrants are welcome here!”]

Nancy Ukai: It was in July. About a hundred people who were there at the pilgrimage got together after the traditional service and had a rally, and basically these were survivors. Some of them were in their eighties and even nineties, possibly, and were holding up signs saying, “Families Belong Together,” “No More Separation,” “Protect The Children,” and directly tied their incarceration experience as children and survivors of the camps to what is happening now. And it’s like, It can happen again. It is happening again. It’s happening now. So this idea of “never again” is like, no, it’s happening now.

[Natural sound: Tsuru for Solidarity protesters, “No hate, no fear, immigrants are welcome here!”]

Multiple narrators: “Camp,” “Topaz,” “Manzanar,” “Camp,” “Detention Centers,” “Camp,” “Mass Incarceration,” “Topaz,” “Camp,” “Manzanar,” “Camp,” “Incarceration,” “Topaz,” “Manzanar,” “Camp,” “Topaz,” “Camp.”

[Newsreel from the 1940s with music: “Evacuation. More than 100,000 men, women, and children—all of Japanese ancestry—removed from their homes in the Pacific Coast states to wartime communities established in out-of-the-way places. Ten different relocation centers in unsettled parts of California, Arizona, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arkansas.”]

Devin Katayama: One day after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States Congress declared war on Japan.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: Just a couple of months later, on February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order authorized the government to forcibly remove Japanese American civilians—even American-born citizens—from their homes on the West Coast, and put them into incarceration camps shrouded in barbed wire and patrolled by armed guards for the duration of the war. This imprisonment uprooted families, disrupted businesses, and dispersed communities—impacting generations of Japanese Americans.

Susan Kitazawa: I remember my parents talking about going on the street and seeing those executive order signs tacked up on windows and telephone poles. They were out there in public just saying, “If you’re of Japanese ancestry, on this date at this time you need to show up at such and such a place.”

Devin Katayama: This is Susan Kitazawa. She’s a Sansei. Her family was incarcerated at Manzanar.

Susan Kitazawa: The whole thing of being shipped off to camp, you could only take two pieces of luggage, and whatever you took with you, you had to be able to carry yourself. Um, you know, just the suddenness of it, that, okay, your life has just been torn apart and you need to pack up what you can carry and show up at this place, you know, the assembly center…and not knowing what was going to happen to you.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: They were given just a few days to pack up their belongings, shutter their businesses, sell whatever they could—often for cheap. They had to uproot their lives before reporting to assembly centers. For most of the Japanese Americans in the Bay Area who would end up in Topaz in the middle of Utah’s desert, they had to report to the Tanforan Assembly Center just south of San Francisco. Japanese Americans in the Los Angeles area reported to the Santa Anita Assembly Center before being forcibly removed to Manzanar in California’s arid Owens Valley. Both assembly centers were active horse racetracks. Margret Mukai, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Tanforan and then Topaz, remembers hearing about this from her mother.

Margret Mukai: When the Executive Order 9066 came down, they had six days, she told me, to pack up everything, take only what you could carry. She had to close the florist business, do all the books, she said, and physically close it. She arrived to Tanforan very tired from all this.

Devin Katayama People were forced to sleep in horse stalls. Here’s Kimi Maru, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Tanforan.

Kimi Maru: It was terrible. They were living in a horse stall. Yeah, my mother, all she said was how awful it was, the smell of horse manure, waking up to that every day. It was pretty filthy. She had nothing good to say [laughs] about, about that experience at all.

[Newsreel from the 1940s: “The food is nourishing but simple. A maximum of 45 cents a day per person is allowed for food. And the actual cost is considerably less than this, for an increasing amount of the food is produced at the centers. A combination of oriental dishes, to meet the tastes of the Issei, born in Japan, and of American-type dishes, to satisfy the Nissei, born in America.”]

Devin Katayama: Kimi’s family was sent to Topaz from Tanforan. Life in camp was difficult. Kimi remembers her mother talking about how even the simple things in Topaz were hard.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Kimi Maru: As far as food went, she really said the food was terrible. She remembers getting food that had maggots in it. She said that they used to be served Spam a lot, which is why she really didn’t like it. You know, we never really grew up eating Spam much at all, because it reminded her of camp.

Devin Katayama: Incarceration didn’t just have a profound impact on families and individuals. It also had an impact on the Japanese American community as a whole. This impact continued beyond the time they spent in camp, long after the last camp closed in 1946. Here’s Bruce Embrey, a Sansei whose mother was incarcerated at Manzanar.

Bruce Embrey: The legacy is that this is not some static, little episode in history that we go back to and pay homage to.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Bruce Embrey: It’s something that is to be learned from and applied. And that’s what my mother did. My mother learned from her experience in camp and applied it in her life. When she assessed what happened to her in Manzanar, she said, “We had no political power, we were a young, immigrant community, we had no allies.”

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: It wasn’t just the survivors who carried the scars from that history, but also their children, their grandchildren. Many Japanese American families didn’t discuss what happened in the camps. It was common for older Issei and Nisei generations to be completely silent on the topic.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Devin Katayama: Jean Hibino, a Sansei whose parents were incarcerated in Topaz, remembers being told:

Jean Hibino: “Don’t rock the boat, don’t make waves, don’t stick your neck out. Why do we want to do this? We’re okay. Why do we want to bring up old wounds?”

Devin Katayama: But as time went on, some younger Japanese Americans did want to reopen these wounds. Sansei activists felt that in order to empower themselves and find allies, the Japanese American community wanted to talk about how they were treated during World War II, and they wanted to share these memories with others. This led to decades-long activism by individuals and groups like the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, called the redress movement. Japanese Americans and other allies fought the United States government for several things. Among them was an apology for this unjust incarceration, and monetary reparations for the harm that was caused.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: Here’s Kimi Maru speaking about the importance of the redress movement to the Japanese American community.

Kimi Maru: But it wasn’t until the redress movement came about and people — Niseis and Isseis at that time — really started opening up and speaking about what they went through. Before that, many people, especially Sanseis, never even heard their parents utter a word about it. You know, it was just not something that people spoke about.

Devin Katayama: Redress helped break these intergenerational silences.

Kimi Maru: It was through the redress movement that I think it really, uh, brought the community together and really opened up a chapter in history that needed to be talked about. The younger generations needed to learn about what people went through.

Devin Katayama: The redress movement picked up steam in the 1970s and ’80s. It led to official Congressional hearings as part of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. In 1981, Congressional hearings were held for twenty days in cities across the country: Los Angeles; San Francisco; Washington, D.C.; Seattle; Chicago; Cambridge; New York; Anchorage; and the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands. During these hearings, survivors of incarceration publicly shared their stories. Kimi Maru says that testimony was moving.

Kimi Maru: And then when the Commission hearings happened, that was when there was such an outpouring of people sharing what had happened to them, things that most people had never even heard of, as far as what people lost, in terms of their houses or businesses, their belongings, you know, the conditions in camp itself.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Devin Katayama: Here’s Hans Goto, a Sansei whose family was incarcerated first at Manzanar and later at Topaz.

Hans Goto: When they got to Los Angeles, unbeknownst to me, uh, my father decided to give testimony. I think that was the first time he ever told the story to the public. My father spoke about how difficult it was and how emotional it was, and that really struck me more than anything else. It’s like that’s part of the history of the “camps,” in quotes, that we never heard. You know, we always heard, “Oh yeah, we went to camp and we met so and so.” There’s some really heartfelt stories of deprivation, things being taken away, their whole life being turned upside down and so on.

Devin Katayama: Rev. Michael Yoshii is a Sansei whose family was incarcerated at Topaz. He was in the room when person after person would get up to tell their story.

Michael Yoshii: There were three days of hearings in San Francisco, and my parents came to all of them. You know, so many people that I had known in the community came to the hearings. And it was just so profound, the energy there.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Michael Yoshii: I think there were like 500 people in the room. And just the gripping testimonies from, from Isseis, from Niseis, and Sanseis like myself. You can, um, feel people just listening to every word. It was a very cathartic experience for me personally. It was clearly a cathartic experience for our whole community.

Devin Katayama: Bruce Embrey’s mother, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, testified at the Los Angeles hearings on August 5, 1981. She joined over 150 survivors of incarceration and descendants in sharing their stories and appealing for justice. In her testimony, she said: “The period I spent in Manzanar was the most traumatic experience of my life. It has influenced my perspective, as well as my continuing efforts to educate, persuade, and encourage others of my generation to speak out about the unspeakable crime.” Here’s Kimi again reflecting on the impact of redress.

Kimi Maru: It was a pretty intense movement that finally resulted in President Reagan passing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and signed it, which recognized that the government had made a mistake: it was wrong; it was based on racist, wartime hysteria and lack of leadership; and then $20,000 reparations for those who went through that experience.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Kimi Maru: No one felt that that was enough money, that would ever, you know, pay for what people lost, but it was at least a recognition that it was wrong.

Devin Katayama: Redress was also an exercise for the Japanese American community in growing political power and building coalitions. A lot of the same people who pushed for redress were involved in other social justice movements like civil rights, Yellow Power, and the anti-Vietnam War protests.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: What happened to Japanese Americans during World War II helped ignite decades of political activism. For many in this community, the history of incarceration is a call to action. Kimi Maru remembers growing up with this activism.

Kimi Maru: My parents used to go to all the anti-war marches that were in San Francisco against the Vietnam War, from really early on, when these marches first started. And I was pretty young then. I, I just kind of grew up going on anti-war marches. [laughs]

Michael Yoshii: Once I got into Berkeley, there was a lot of anti-war protests going on, and I started joining some of them. But for us, as Asians, looking at what was going on in Vietnam. I think there was a visceral reaction to that particular incursion into Vietnam.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Devin Katayama: That was Rev. Yoshii again. And this is Bruce Embrey.

Bruce Embrey: I think this is a quote from the amazing woman, Audre Lorde, where she says, “Silence will not protect you.” And my mother used that a lot, “Silence would not protect us.” She says, “If you think that the US government is no longer rounding up Asians and incarcerating them in concentration camps, look at what’s happening in Vietnam and Indochina. US imperialism is, just as it did to us, still utilizing racism to oppress Asians and Asian Americans.”

Devin Katayama: On September 11, 2001, the United States was hit by the largest terrorist attack in its history.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Devin Katayama: The attacks were carried out by al-Qaeda, a terrorist organization then based in Afghanistan. In the wake of these attacks, the United States went to war, as hate crimes and xenophobia against Muslims and Arab Americans went up. For Japanese Americans, this wartime hysteria seemed all too familiar. Rev. Yoshii remembers it this way:

Michael Yoshii: The first Sunday after 9/11 I had just an open conversation with people, like many Christians were doing, to just debrief what was happening. And one member really brought up his memories of Pearl Harbor, and how immediately the Nisei and the Issei were targeted as the enemy. And he was concerned about what’s happening with Arabs and Muslims and South Asians, because he knew that they would be a targeted enemy that could be vulnerable in the American context. The next week I invited an Imam to come speak to us. And then we began working with the local Afghan community. And the parallel was that the FBI was coming into Muslim communities at this particular time doing surveillance and monitoring things then. That happened with Japanese Americans, too. Many of us knew that there would be a time where the Civil Liberties Act would be important for other communities. It’s not just about ourselves, but it’s going to be a principle for others. And I think that really came home in 9/11.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Devin Katayama: Many Japanese Americans wanted to show support for Muslims and Arab Americans, advocating as their allies. In return, some of these communities have remained connected. Here’s Roy Hirabayashi, a Nisei whose family was incarcerated in Topaz.

Roy Hirabayashi: Over the years, the Japanese community has really tried to connect and support other communities in distress or having their own challenges.

[Instrumental music fades in]

Roy Hirabayashi: So the Muslim community naturally was being supported, you know, the Latino community for immigration issues.

Devin Katayama: And that solidarity between communities is mutual for many. February 19th is called the Day of Remembrance. It’s a time to acknowledge the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Roy has been going to these events for years.

Roy Hirabayashi: Over the past ten years, the attendance for the Day of Remembrance has really increased. Before we were happy if maybe a hundred people come. Now, you know, it’s like standing-room only. And it’s not just the Japanese community, but just different folks from the larger communities coming out for this event, too.

Devin Katayama: Which brings us back to Tsuru for Solidarity. For these activists building coalitions, the past and the present will always be connected—because of incarceration, because of redress, because of their history of organizing.

Nancy Ukai: Tsuru for Solidarity has become a place where people have particular political interests—prison abolition, HR 40 to support Congressional legislation for Black reparations—that’s another thing that Tsuru for Solidarity is doing.

[Instrumental music fades out]

Nancy Ukai: So I think all of these ways of connecting and becoming an activist voice is just really important.

Devin Katayama: That was Nancy Ukai. Here’s Kimi Maru again.

Kimi Maru: I think because Japanese Americans were able to win redress by organizing in our community and telling the stories about what happened to us, we wanted to share with people in the African American community, and just let them know that we’re behind them. And we want them to know that it’s possible to win. Getting the government to admit when they’ve done something wrong and to redress it is something that everyone has a right to do.

Devin Katayama: Many descendants believe staying silent about the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II won’t protect people facing injustice today. And for some of them, taking action is an obligation. They feel they need to speak out to prevent history from repeating itself. Susan Kitazawa, who was interviewed by Amanda Tewes, agrees.

Amanda Tewes: Susan, what do you think motivated you to get involved in these ways?

Susan Kitazawa: That’s a funny question. [laughs] I think my question is: why isn’t everybody doing that? [laughs] Like aren’t we here to do that? You know, there’s a lot of uneven playing fields in the world and in our lives. There’s a lot of things that aren’t just, and it’s our responsibility to do what we can to fix that.

[Theme song fades in]

Devin Katayama: Thanks for listening to “‘From Generation to Generation’: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration” and The Berkeley Remix. Next time: the history, legacy, and contested memory of Japanese American incarceration during World War II.

This episode features interviews from the Oral History Center’s Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Oral History Project, and includes clips from: Bruce Embrey, Hans Goto, Jean Hibino, Roy Hirabayashi, Susan Kitazawa, Kimi Maru, Margret Mukai, Ruth Sasaki, Nancy Ukai, and Rev. Michael Yoshii. Music from Blue Dot Sessions. Additional archival audio from Tsuru for Solidarity and the National Archives. The transcript from Sue Kunitomi Embrey’s testimony comes from the Los Angeles hearings from the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. This episode was produced by Rose Khor, Roger Eardley-Pryor, Shanna Farrell, and Amanda Tewes. Thank you to the National Park Service’s Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant for funding this project. To learn more about these interviews, visit the Oral History Center’s website listed in the show notes. I’m your host, Devin Katayama. Thanks for listening, and I will talk to you next time.

[Theme song fades out]

Today, we’re sharing the first episode of the new season of the Berkeley Remix, a podcast by UC Berkeley’s Oral History Center. The four-episode season, called “From Generation to Generation: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration,” centers the experiences of descendants of Japanese Americans incarcerated by the U.S. government during World War II. It explores themes of activism, contested memory, identity and belonging, and creative expression as a way to process and heal from intergenerational trauma. This first episode is called “It’s happening now: Japanese American Activism.”

Emily Ehlen/Oral History Center

Read a Q&A with the Oral History Center’s Shanna Farrell about the project:

When oral historian Shanna Farrell began interviewing descendants of Japanese Americans incarcerated by the U.S. during World War II, she didn’t make any assumptions.

“They are not monoliths,” said Farrell, who has been on staff at the Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center since 2013. “Each person has experienced their ancestors’ incarceration differently — some are deeply affected and have spent their lives processing and expressing the trauma, and for some, they aren’t affected as deeply.

“The project, called Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives, explores the ways that intergenerational trauma and healing happened after incarceration. Farrell, along with the Oral History Center’s Amanda Tewes and Roger Eardley-Pryor, interviewed 23 descendants whose ancestors were incarcerated in two prison camps — Manzanar in California and Topaz in Utah. The interviews explore identity, community, creative expression and the stories families pass down.

“There has been a ton of work done on survivors of the WWII incarceration camps,” said Farrell. “We were really focused on how stories get passed down. We approached the project wondering: Does that trauma get passed down intergenerationally? And if it does, is healing possible?”

From more than 100 hours of interviews, Farrell and her team produced the series, “From Generation to Generation: The Legacy of Japanese American Incarceration.” It’s the eighth season of the Oral History Center’s podcast, the Berkeley Remix.

Berkeley News talked with Farrell about the project and the new podcast season.

Can you tell me about the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives Project? How did it begin, and who did you interview?

The project started in April 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic lockdown. It was funded by the National Park Service through the Japanese American Confinement Sites Program Grant. We wanted to focus on trauma and healing in the generations that came after the survivors of the Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII, and we used healing as a throughline on which to center the project and interviews.

We talked with 23 descendants of survivors over Zoom for about four hours each — two sessions of two hours — and collected over 100 hours of interviews. People either nominated themselves or someone they knew, so it was more of an opt-in project rather than trying to find people to participate. The people we interviewed, whom we call narrators, ranged in age from people in their 30s to people in their 80s, so we interviewed several generations.

Emily Ehlen/Oral History Center

Why did you choose to focus on descendants’ experiences?

There has been a lot of work done about the survivors of the Japanese American prison camps and much less about the legacy of their incarceration — how it impacted generations after them. I think it’s important to move past the dominant narrative that survivors’ experiences are the only ones that matter and to examine the legacy of trauma and how people have found their way through it.

The reality is that 120,000 people were forcibly removed from their homes and put into prison camps for no other reason than their race and heritage. Then, when the camps closed, many had to start over. So many people lost everything and were basically given a pittance and a bus ticket. It uprooted and devastated a lot of different communities, and that legacy continues today. And I think if we ignore the experiences of descendants, we’re actually ignoring history, because it does continue; it’s not a static thing. And it’s important to think about the ripples of this today, so we don’t repeat them in the future.

For the podcast series, what themes did you explore?

We decided to focus on four major themes that emerged from our interviews. In the first episode, we started in the present with activism and how survivors and descendants built diverse coalitions and became involved in social justice issues, from the anti-Vietnam War movement to family separation at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Courtesy of Oral History Center

In the second episode, we took a step back and talked about the history, legacy and contested memory of the incarceration. Contested memory is a big theme because descendants grew up hearing different stories from their families or in their research; it wasn’t firsthand for them. So we examine the idea of who gets to tell a story or who a story belongs to.

Next, we explored identity and belonging in the Japanese American community — about what it feels like to be between two worlds. A majority of narrators talked about travel to Japan and how significant that was. We [the interviewers] were not expecting that at all. But it was complicated for them. In that episode, we included someone saying, “I’ve never felt more Japanese than when I’m in America, and I’ve never felt more American than when I’m in Japan.”

That goes back to when you were talking about how descendants aren’t monoliths — that they have multiple identities and complex feelings that interconnect and diverge from one another’s.

Yeah, and one way these different identities often came through was in the food they ate. We talked with them a lot about food and what they ate during the holidays. One person who was Korean American and Japanese American grew up eating Korean food as her comfort food. Another person usually ate American food, like chicken nuggets. Someone else was a descendant of a Holocaust survivor, and their holiday meals were European and Japanese and even Italian, because they had a housekeeper who was Italian.

And in the last episode, you explore the ways that descendants process the history and intergenerational trauma through creative expression and memorialization. Can you tell me about that?

Yeah, a lot of people talked about the importance of art in their lives and expressing themselves through art. Some descendants embraced art and public memorialization about incarceration history to honor the experiences of their ancestors and as ways to work through the intergenerational impact of this incarceration. Others seek healing by going on pilgrimages to the actual sites of incarceration, where they reclaim the narratives of these places.

Emily Ehlen/Oral History Center

How did you prepare for and approach these interviews, given the sensitive and potentially traumatic nature of the subject matter?

There’s a subgenre of oral history called trauma-informed interviewing. I got my master’s degree at Columbia University in their oral history master’s program, where there was a heavy focus on trauma-informed interviews. And for this project, we did a lot of reading of new literature about how to approach these interviews. At the end of the day, trauma comes up in places where you least expect it.

We thought about this a lot, in terms of project design. We asked ourselves, “How do we talk about traumatic events in a way that doesn’t feel too risky or too much for the narrators?” And much of that is baked into the oral history process.

First, we have a pre-interview with the narrator, where we go over what we’re going to be talking about and how, so that they’re prepared mentally, emotionally and intellectually before the actual interview. We let them know that they can stop or withdraw from the process anytime. Then, during the interview, we ask permission to talk about specific topics and pick up on cues if they don’t want to discuss something. And finally, we have the interviews transcribed and ask the narrators to review and edit them, although we like to keep transcripts as close to the actual audio as possible. We have had people request to seal the interviews, and we don’t make them public unless narrators give their permission. We give narrators a lot of control over what happens.

How were you able to support the narrators after they did these interviews?

One of our project advisers, Lisa Nakamura, is a psychotherapist, and she is a descendant herself, and she specializes in intergenerational trauma. She does something called healing circles, which is basically group therapy. In this case, she led healing circles to help narrators process their interview experience. And we offered that to narrators as a resource, along with a list of other resources. None of us were there or knew who went or anything. It was purely for them to process their experience and the feelings that came up, if they wanted to.

What do you hope people take away from this podcast and larger project?

I hope that people, if they don’t know about this history, now they do. Not everybody knows this history. I’m from the East Coast, and I didn’t know about it until I moved to California and did one of my first oral history interviews with a woman whose ex-husband’s family had been incarcerated and then experienced housing discrimination in Berkeley. And that feels terrible, that many of us in the U.S. aren’t educated about this history.

I also hope it helps show that things like incarceration have a long legacy that continue today. And that it helps us all understand that this traumatic event is maybe a part of who a person is, but it doesn’t define them if they don’t want it to. And there are a lot of positive things that can grow from it, like artwork and music. And I’m always happy when people listen.

Listen to the new season of the Berkeley Remix, “From Generation to Generation.”

Learn more about the Japanese American Intergenerational Narratives project.