UC Berkeley students combat K-12 book bans by creating their own children’s books

Ivan Natividad/UC Berkeley

January 29, 2024

Berkeley Changemaker is a Berkeley News series highlighting innovative members of the campus community engaged in work and research that tackles society’s most pressing issues.

As the battle to control what students read continues in K-12 schools across the country, policies backed by U.S. legislators have contributed to a recent rise in the banning of books that include the history and experiences of people of color.

Those stories, historically, have been left out of American history books, said UC Berkeley lecturer and anthropologist Pablo Gonzalez, so it’s important to combat that exclusion now more than ever.

And Gonzalez is doing just that, having found an innovative and engaging way for his students to help stop the erasure of history.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

By writing and illustrating their own children’s books.

Students from Gonzalez’s Introduction to Chicano History course spent the fall semester researching Chicanx history, centering their scholarship on the experiences and historical contributions of Chicanx women and the marginalized communities they come from.

These included labor and civil rights activist Dolores Huerta, who, with Cesar Chavez, co-founded the United Farm Workers Association, and the 1969 Third World Liberation Front Strike, a movement that led to the nation’s first ethnic studies college programs.

Students then used those histories to produce original narratives and illustrations in storybook form for elementary grade students. Those books are currently accessible in digital form, said Gonzalez, and hard copies will be published for distribution to states and school districts where this history is openly banned.

“We want to be intentional about sending them out as a package to schools in places where these books, in a sense, have been deemed to be contraband by state officials,” said Gonzalez, who is also a Berkeley alumnus. “In this political climate, where the erasure of Chicanx and Latinx stories in schools is literally being discussed in halls of power, we need more access to stories that center this history.”

Gage Skidmore/Flickr

In the U.S., school book bans rose by 33% in 2023, with over 3,300 cases of books being excluded, up from 2,532 in 2022, according to a recent report. Florida accounts for more than 40% of book bans in the last school year, followed by Texas, Missouri, Utah and Pennsylvania.

A majority of banned books, which some lawmakers have called “obscene,” include characters with LGBTQ+ identities, people of color, and focus on race and racism. In response, lawsuits have been filed to challenge the bans, and some politicians have begun to dial back the rhetoric and censorship that most Americans feel has gone too far. In California, the recent implementation of ethnic studies curriculum requirements in K-12 schools also signals the importance of young students having more access to the history of these marginalized communities, Gonzalez said.

“There are very few children’s books that are not only age appropriate, but that also speak to these underrepresented groups,” Gonzalez said.” So Berkeley students have created books that are not only historically relevant, but stories that children can relate to.”

A rare community space

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

But telling a story that holds the attention of young children can be challenging.

To aid the creative process for 120 students, Gonzalez booked an active learning classroom in Wheeler Hall, equipped with movable desks, breakout boards for group dry erase sessions, and individual monitors for students to plug in their computers to view and conduct presentations.

Ivan Natividad/UC Berkeley

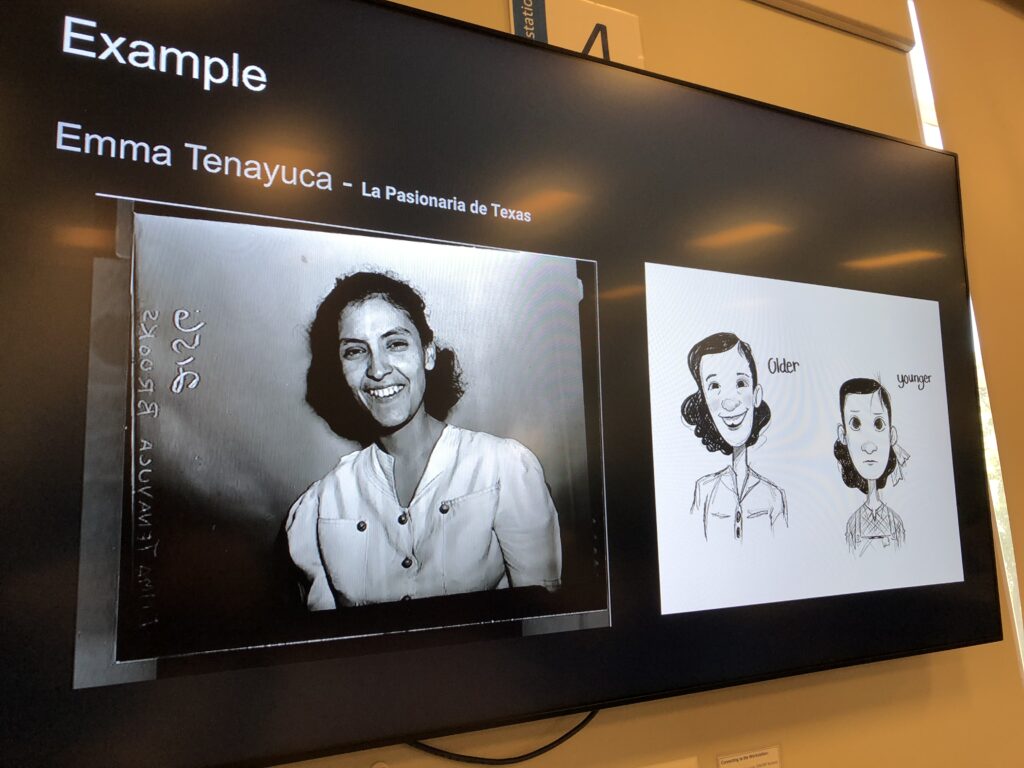

Gonzalez also tapped the services of a local illustrator and character designer, Nathalie Bernal, who supported 30 groups of students. Bernal mentored them, encouraging them to “think like a kid” in their choice of illustration style and in the development of visuals for their books.

“The students really broke out of their molds to think about images that children would be drawn to,” said Bernal, who is Mexican American. “I’ve never taught in a class like this where the students and teacher were so receptive and open to different creative processes. It was a pretty rare community space to be in. It makes me want to delve more into the history they pulled from.” Second year computer and data science major Alexa Rodriguez illustrated her group’s project, Bonbon: Y las mujeres unidas!

The book focuses on the experiences of female mutualistas, who were Mexican American women that supported community-based societies in the 1930s during the Great Depression.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

Written in both English and Spanish, the story’s main character, a Chihuahua named Bonbon, was inspired by Rodriguez’s dog, Luigi.

The book follows Bonbon and his best friend, Lucia, a 7-year-old girl whose family is experiencing economic hardships and racial discrimination. The women in their neighborhood work at a pecan shell factory and are paid less because they are Mexican. In the end, the women and Bonbon come together to strike for better working conditions and resources for their community.

Courtesy of Alexa Rodriguez

Rodriguez said illustrating the book allowed her to express herself artistically. She hopes to one day read the book to children in the Oakland community that she comes from to “inspire a new generation to stand up for their own rights.”

“This is one of the best classes I have ever taken,” said Rodriguez. “The lectures were so engaging and actually felt more like conversations. Dr. Gonzalez is a teacher who really motivates you to dig deep into the history and find ways to relate to it.”

History’s reflection

Gonzalez found it hard, as a young child in West Berkeley, to relate to history books for students his age. He was drawn to his elementary school library, where he holed up with books, searched for them in the stacks and prodded the librarian for recommendations on books about anthropology, Ancient Greece and the U.S. Civil War.

But while that scholarship opened up a plethora of perspectives on, and representations of, the world around him, he noticed something important was absent from the history that fascinated him so much.

“In every book I opened, and every page I read, I never saw a reflection of myself,” said Gonzalez. “The stories of my community were missing.”

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

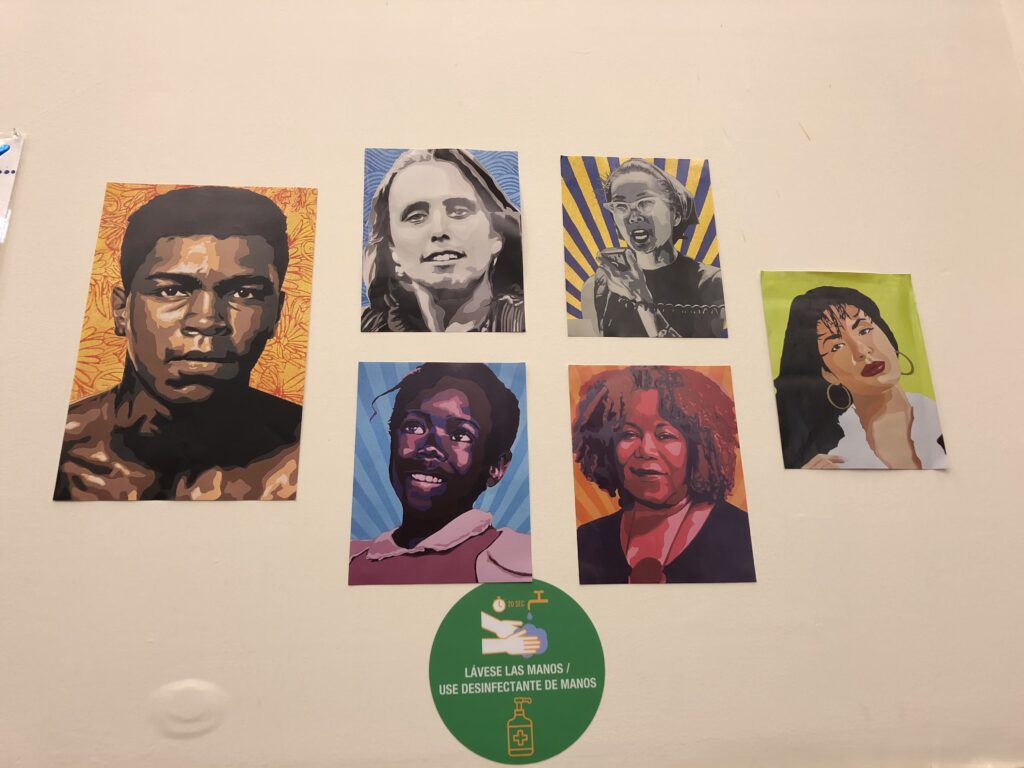

Now a prominent lecturer in Berkeley’s ethnic studies department, Gonzalez went on to dedicate over 20 years of research and teaching to the preservation of that hidden history. Through innovative project-based curriculum and assignments, his students explore Chicanx history and bring it to life by creating art, board games and even cookbooks. And his classrooms become close communities with gatherings like end-of-semester potlucks.

Gonzalez has also led the creation of unique campus initiatives, including Berkeley’s Ethnic Studies Changemaker Scaffolding Stories/Building Communities. The project involves a group of ethnic studies students and faculty members who — through art, podcasts and augmented reality — work with community partners to amplify the stories and voices of marginalized communities.

His dedication to this work on campus was recognized in 2022 when he received Berkeley’s Distinguished Teaching Award. Keith Feldman, chair of the Department of Ethnic Studies, said Gonzalez has enhanced student experiences by creating one-of-a-kind spaces of inclusion and belonging for them.

“Pablo continues to contribute innovations in ethnic studies pedagogy, and he finds unique ways to think about knowledge and how it constructs the world around us,” said Feldman. “Through his teaching, he empowers his students to connect to the curriculum on a personal level. And they leave his classes inspired to take action in their communities.”

Bridging the divide

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

Gonzalez said his students also are learning, by being at Berkeley, the history of the formation of ethnic studies as an academic field. “They are beginning to see themselves as part of that legacy,” he said, and wanting to contribute to the greater good.

“Many of my students have experience in community advocacy and youth mentorship at local high schools, and some have aspirations of becoming teachers,” said Gonzalez. “Many of them are also storytellers and artists, and this book project has given them an opportunity to see themselves as historical actors.”

Courtesy of Poinciana Hung-Haas

One of them is Poinciana Hung-Haas, a first-year student from Oakland whose group produced the book, They Didn’t Know We Were Seeds. The story follows a little girl named Chia and her village of Indigenous farmers in Mexico. Chia’s community is displaced by the government and rich corporations that want their land.

They are forced to find a new place to live.

While adults in her village gather to find ways to get their land back, the children are left out of the discussions. But Chia organizes the children in her village, and they plant flowers across the land to “sow the seeds of rebellion.” That leads to the entire village joining the fight and creating a sovereign home away from the corrupt government.

Courtesy of Poinciana Hung-Haas

The book was inspired by the struggles of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, said Hung-Haas, a group in Chiapas, Mexico, that have become a symbol around the world for Indigenous sovereignty.

As a very active community organizer in Oakland’s Chinatown community, Hung-Haas said learning about the history of the Zapatistas and what they have fought for, allowed her to relate to that struggle, despite not being Chicanx.

She hopes the book will help children from all backgrounds realize they can make a difference in their communities, despite being young.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

“A lot of people see history as something that grounds themselves in their own culture,” said Hung-Haas, who majors in urban studies at the College of Environmental Design. “But we need to understand the history and contributions from all different types of communities. We can’t be afraid to learn about uncomfortable truths. We need to understand all of that history so we can create bridges to connect where we are divided.”

‘We will not stop’

Ivan Natividad/UC Berkeley

Through funds provided by Berkeley’s Ethnic Studies Fifth Account and Thriving Initiative, Gonzalez will publish hard copy versions of his student’s books through Eastwind Books, a publishing company owned by Harvey Dong, a Berkeley ethnic studies lecturer.

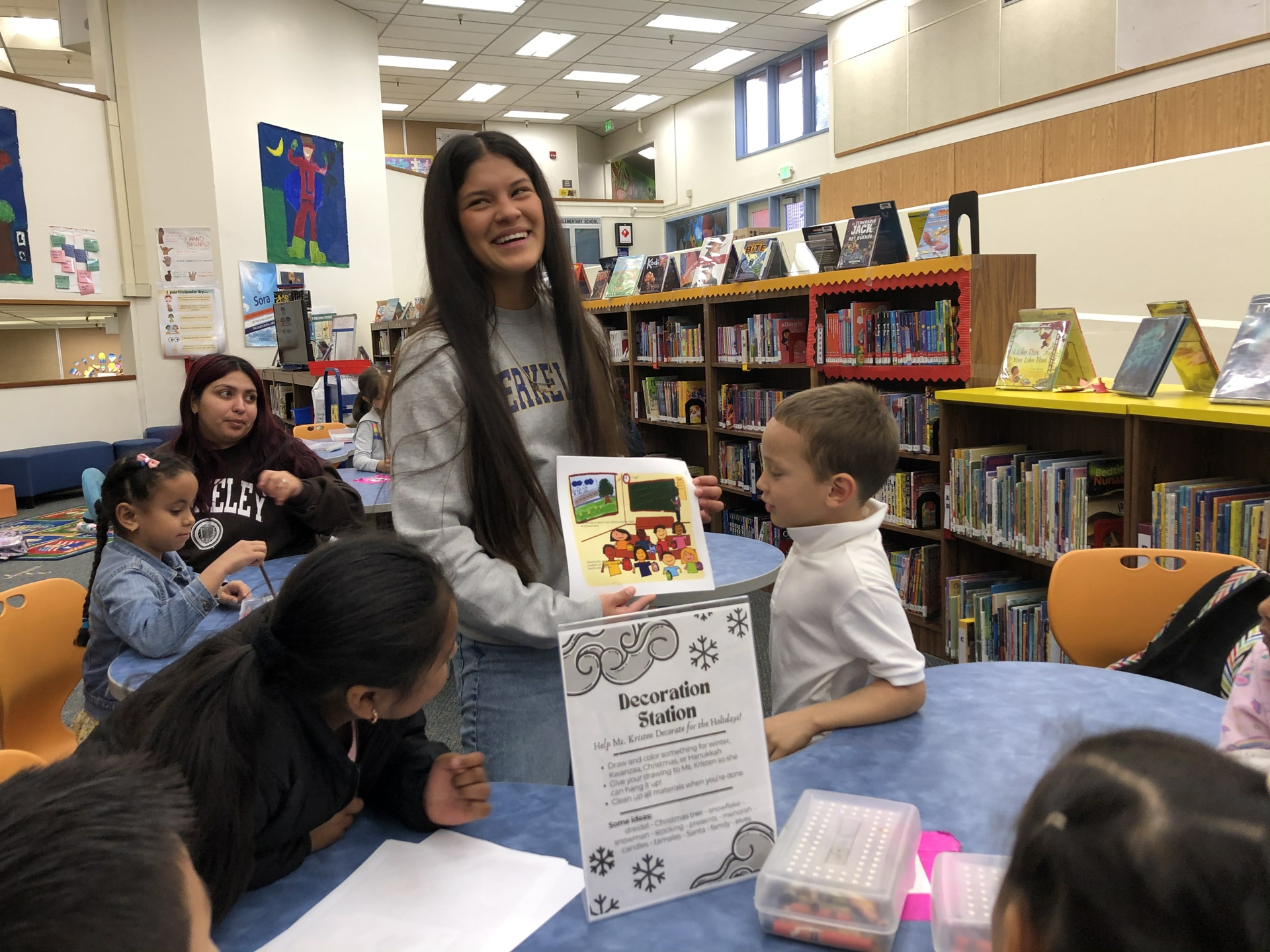

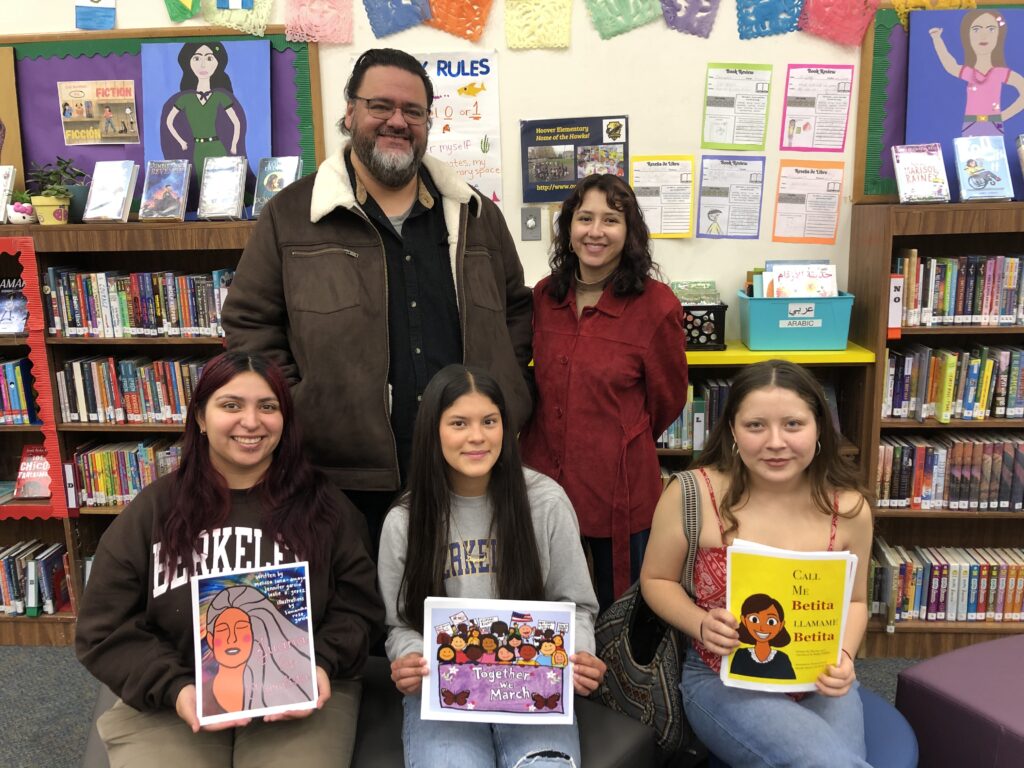

Last month, students from Gonzalez’s class visited Oakland’s Hoover Elementary School to read their books to third grade students. The school’s librarian, Berkeley alumna Kristen Flores, has previously collaborated with Gonzalez to give his students opportunities to tutor and mentor children at the school.

“I took several courses with Pablo when I was a student, and he always found engaging ways to make learning history a personal journey,” said Flores. “I’m hoping to include these books in the collection of our library here at the school, moving forward, because they are stories our kids can relate to.”

Ivan Natividad/UC Berkeley

But for Gonzalez, the distribution of his students’ books won’t stop there. He plans to reach out to elementary schools across the country.

“It doesn’t take much for students to be inspired,” Gonzalez said. “So we are responding to these book ban policies, to tell them, we will not stop producing our stories.”

At Hoover Elementary, in a crowded library of eager and curious third graders, Berkeley student Lilia Evans read her children’s book, Call me Betita, which follows the life and times of Elizabeth Martinez, a civil rights activist, journalist and Chicanx female icon.

For Evans, the experience was both nerve-wracking and fulfilling. “It can be really difficult to keep their attention, but you can see that some of them were really impacted by the story,” she said.

That was evident when Evans received hugs and “thank-you’s” from several students afterward. One little girl said, “I loved your book!” Another child had asked, while Evans was reading the story, “Why is [Betita] holding an award?”

Evans responded, “Because she knows who she is. She knows where she comes from. … She’s winning.”