As a kid, he learned men don’t cry. As an art practice student, he’s challenging that.

Photographer Brandon Sánchez Mejia, whose cohort is part of UC Berkeley's Department of Art Practice's 100th year, showcased his senior thesis project, "A Masculine Vulnerability," in the campus's Worth Ryder Art Gallery last semester.

Keegan Houser

February 6, 2024

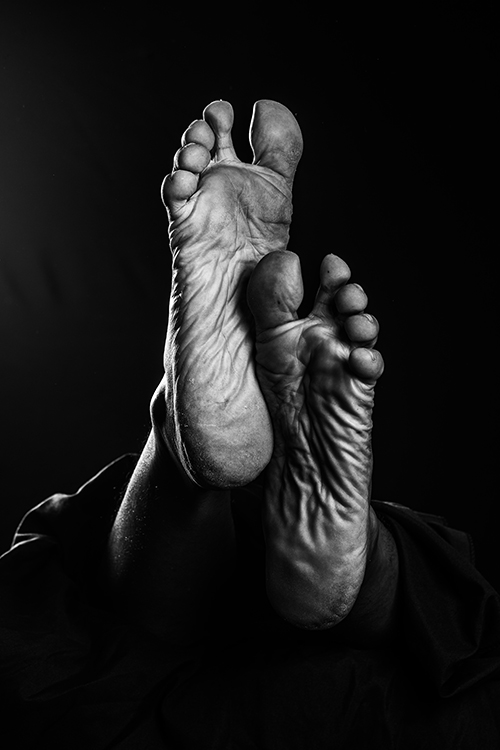

Brandon Sánchez Mejia stood at a giant wall in UC Berkeley’s Worth Ryder Art Gallery and couldn’t believe his eyes. In front of him were 150 black-and-white photos of men’s bodies in all sorts of poses and from all sorts of angles. It was his senior thesis project, “A Masculine Vulnerability,” and it was out for the world to see.

“It came from this idea that as men, we are not allowed to show skin as scars or emotions or weakness,” said Sánchez, who will graduate from Berkeley this May with a bachelor’s degree in art practice.

Sánchez’s cohort is part of the Department of Art of Practice’s 100th year, a milestone that department chair Ronald Rael said is cause for celebration.

UC Berkeley Department of Art Practice

“There have been moments in art practice’s history when it was unclear that art should be at a university at all,” said Rael, a professor of architecture and affiliated faculty in art. “And here we are, at 100 years, and it’s one of the most popular majors on campus.”

We live in a moment where the arts can be a vehicle to discuss complex issues in ways that other forms of expression can’t, said Rael. Art practice often involves deep explorations into research and can have important political motivations and impacts.

“It’s a discipline that is really reflective of individual truths,” he said. “And I think one thing that’s very beautiful about being an artist is that you can tell those truths in a way that allows others to see them.”

For Sánchez, showing his true self in “A Masculine Vulnerability” felt scary, but it was something the photographer felt he had to do.

Exploring another side of masculinity

As a kid growing up in El Salvador, Sánchez was sensitive — he felt connected to nature and animals and was often moved to tears. But he learned from his dad that crying wasn’t what men did.

“My dad had this machismo mindset,” said Sánchez. “If I was crying, he’d say, ‘Don’t cry.’ He’d get mad if I was crying. Now, I’m trying to break the cycle.”

In “A Masculine Vulnerability,” there’s a close-up of an eye, crinkled soles of feet, hands intertwined and in clenched fists, fingers squeezing skin and stretch marks. In the people’s bodies, you can see details — pores, lines, blood vessels — that you normally wouldn’t.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia

During the photoshoots for the project, Sánchez made sure his models were comfortable. Most of them are his friends, a few friends of friends. Although every photo shows only bare skin, everyone was wearing some clothing. And to each of them, he explained his thinking behind the project and made clear they were in control throughout the process.

“I’d ask, ‘How do you feel in this moment? How do you feel being vulnerable right now?’ Just making sure they were comfortable and that I wasn’t crossing any boundaries. Photography, for me, is about the emotional connections I make with people.”

Sánchez also was a model for the project — he set up a tripod in the studio and had help from a friend — which he said was a big commitment.

“I grew up with low self-esteem issues and scared of failure,” he said. “But in the past year, I’ve been working on showing myself, trying to see all the good things that I have and learning to love myself, in my skin, right now. I couldn’t ask the models to be vulnerable if I couldn’t be vulnerable myself.”

“It’s really brave to put your artwork out there in the world,” said Stephanie Syjuco, an assistant professor of art practice, who encouraged Sánchez to print and present his project.

“Brandon’s installation took up the entire wall,” she said. “To project those images, not just on a screen, but in front of the viewer, it actually had a kind of physical relationship to the viewer’s own body.”

Brandon Sánchez Mejia

Syjuco, who taught Sánchez in her Art and Archive course last semester, said that through the creative process artists develop the ability to fail and pivot, skills that help them succeed in so many fields of study.

“I’ve heard from other professors in STEM or more research-based fields that they notice how brave art practice students are to just jump into a project, to leap into the void, and to be confident in the unknown,” she said.

For Sánchez, the art practice department has been a space where he’s felt free to investigate and interrogate his own experiences and to develop his photography practice in a way that’s thoughtful about the culture and community he comes from.

‘This kid wants to study’

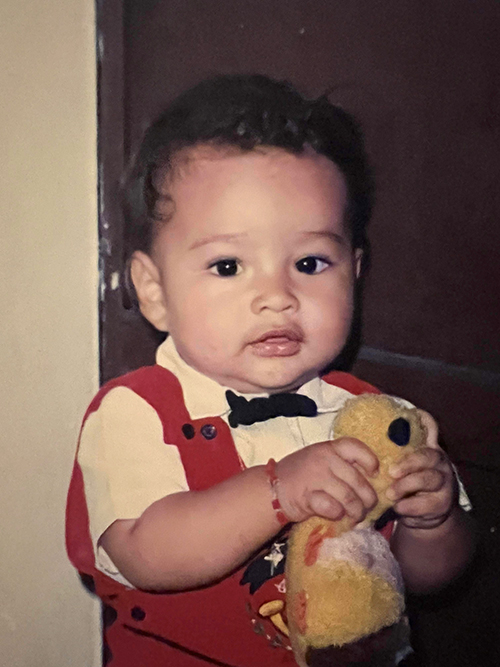

In first grade, at a book fair in San Salvador, Sánchez saw a National Geographic book of photography. He gently turned the glossy pages and gazed at the eagles and lions and zebras — images he’d never seen before. When he had to leave, he didn’t want to put the book down.

Courtesy of Brandon Sánchez Mejia

But it was $27, and he knew his family couldn’t afford it. “That kind of money was not possible for us,” he said. “We were always very poor.”

As a teenager, money got even tighter. Sánchez’s parents separated, and he and his mom and baby brother bounced from house to house, staying with whichever relative would have them. When Sánchez was 16, they moved in with his aunt and her family in the countryside, in Chalatenango.

Terrified that Sánchez, her oldest son, would be recruited by a gang, his mom made him stay inside the house all day, except Sunday, when he was allowed to walk across the parking lot to church.

“She was so scared of the violence in the country,” said Sánchez. “She was trying to protect me, and I trusted she knew what was best for me.”

He spent his days standing in front of the kitchen window, watching other kids as they walked to school or played soccer in the plaza. To pass the time, he read anything he could get his hands on — his favorite book was The Little Prince — and he drew pictures of everyday things, like landscapes and fruit and flowers. Kids in the neighborhood saw him through the window and would sometimes stop by to ask him to draw them something or for help with their homework.

After a year, Sánchez couldn’t take it any longer.

“I needed out, to experience the world,” he said.

So against his mom’s wishes and without any money of his own, he decided he would find a way to go to school.

Courtesy of Brandon Sánchez Mejia

People in his neighborhood heard about his plans.

“They were like, ‘This kid wants to study,'” he said. “They could see how serious I was about getting an education.”

And soon, different community members chipped in and bought him everything he needed — a uniform, a pair of shoes, books and school supplies.

And in 2012, at age 18, Sánchez went to his first day of high school.

“It was just so incredible for me,” he said, “like, ‘I’m going to go to school. I’m going to get an education.’ I remember that moment like it was yesterday.”

From there, Sánchez’s world began to grow.

For his birthday, he got a phone with a camera, and he began taking photos, documenting every moment of his life.

“I call myself a memory keeper,” he said. “I love to take pictures of almost everything or anything. I try to communicate my vision of the world or my emotions or my feelings.”

And he found a campaign that helped people get glasses who couldn’t afford them. His eyesight had been getting worse, and he had been diagnosed as legally blind. After waiting in line with $5 in his hand, he ordered his first pair of glasses. When he picked them up and put them on, the details he’d been missing jumped to life. The leaves on the balsa trees were clear. He could see people smiling and talking. He felt alive in a way he never had before. And his photography took on new meaning.

He went on to graduate from high school at 21 and then got a scholarship to study graphic design for a year at a university, where he also took photography classes.

Then, one afternoon, his family got news they’d been waiting 14 years for: They were eligible for their green cards to work in the United States.

In 2016, Sánchez moved with his family to Los Angeles to start a new life.

‘This moment is not forever’

The first year in L.A. was rough. Sánchez didn’t speak much English and could only get a job as a dishwasher. During the day, he scrubbed plates and pots and pans, and at night, he fell asleep wearing headphones playing English phrases and words.

He also enrolled in night classes to learn English. But learning a new language in his 20s was hard and took longer than he’d expected.

Courtesy of Brandon Sánchez Mejia

After a couple of years, Sánchez was feeling stuck and directionless, like all his work in school was for nothing.

One morning, he was peeling potatoes in the kitchen and sliced his finger. He said he remembered thinking, “I really hate this. I really hate this. I really hate this. I don’t want to be here.”

But after a few minutes went by, he could feel something shift within him, and he realized it was just one moment in time — and that he could change his circumstances.

“I was, like, ‘Yes, I hate this moment, but it’s not forever. I need to focus on the good I have right now,'” he said.

After that, Sánchez began enjoying his job more and enrolled at Santa Monica College. He saved up his money, and in 2018 bought his first professional camera, a Canon 80D. He took photography classes, where he learned about lighting and lenses and how to use Photoshop, skills that have been foundational in his work today.

As graduation neared, he began to wonder what was next. He knew he wanted to do more, but wasn’t sure what.

Two counselors from Santa Monica College — Paul Jiménez and José Hernandez — encouraged Sánchez to apply to four-year universities to continue his education. But Sánchez was scared. He couldn’t be that far from his family, he thought. He also told himself he would never get in, and that even if he did, he couldn’t do the work.

“It’s not that I didn’t have dreams,” he said. “It’s just that, for me, these things seemed impossible.”

But it turned out they weren’t, and he was accepted to UC Berkeley, along with all seven other universities — including four UCs — that he applied to.

He said, “That moment changed my life, because, wow, UC Berkeley? I couldn’t believe it.”

In 2022, Sánchez earned his associate’s degree in liberal arts. He began working as a freelance photographer, taking photos for the Local Hearts Foundation, graduation headshots, family portraits, and picked up other gigs when he could.

And in the fall, Sánchez transferred to Berkeley, ready to make the most of the next two years.

After art practice, a bright future

At Berkeley, Sánchez thrived.

“Brandon is such a bright and engaged student,” said Syjuco. “In my class, he was constantly asking questions, wanting to share the projects he was already working on and seeking guidance.”

In art practice, he joined a class of students from all over the country and world, all with different life experiences.

“We have a student body that is incredibly diverse and, I would say, vocal about their positionality,” said Rael. “It’s very important to me, as an educator, to understand how to channel that positionality and to channel the various backgrounds that students have in positive directions.

Courtesy of Brandon Sánchez Mejia

“I see the university as an engine of upward mobility. That’s what the university is for. And if we are not fostering our students in participating in that role, then I think we are falling short.”

But it doesn’t stop with students, said Rael. To truly support a student body of diverse backgrounds requires the presence of professors, guest lecturers and other educators who are reflective of their students’ futures, who show them that they have a path in a particular field or discipline.

In the last year, Rael has worked to increase the department’s faculty for the high-demand major, hiring instructors, including Native American, Black American and Latinx artists, who represent a breadth of intellectual interests and backgrounds and various identities and orientations.

In order to support an ecosystem of professors and students in addressing the challenges and complexities of the moment we live in, said Rael, it’s important to create space where people with different ideological and religious beliefs and who come from different sociological backgrounds feel free and encouraged to engage with one another and to work through differences.

One space in the Department of Art Practice that Syjuco has been making more representative of what students and educators today are thinking about is the Garron Reading Room. It’s a repository of art books, founded in the 1990s, that features thousands of volumes of artist monographs, catalogs, art history texts, books on theory and zines that reflect the past 100 years of teaching.

Jen Siska

As the unofficial archivist of the department, Syjuco has been working with students to go through the collection, figure out where the gaps are and fill them.

“There is an outsized reference to this very European- or Western-dominated art historical narrative,” she said. “That’s not a fault of the department, per se, or even of the faculty, but it’s what happens when you have a pedagogical focus that is mostly on Western or European forms of artwork.”

Looking forward, Syjuco said, art practice students have so many career paths to explore.

“Like more research-based areas of study, the creative fields actually do have lucrative professions and jobs attached to them, but they’re just not as readily visible,” she said.

Students can go on to become professional visual artists or work in galleries or for arts organizations, she said. They can become curators or arts administrators or work in education departments in larger institutions. They can use their art degree to inform a business practice, channeling the bravery they’ve learned as artists to try and fail and try again.

“There’s always that myth of the starving artist or that question of, ‘What are you going to do within our career?'” said Syjuco. “And I think once students kind of get over that hump, or even realize that it is a myth, hopefully their passions can follow.”

Where will art practice at Berkeley be 100 years from now?

“It’s a really interesting question,” said Rael, “because when we look at the histories of the various disciplines and media we teach, often brown and Black bodies weren’t included in those processes, neither representationally nor technologically.

“So I think new kinds of media will emerge. There will be new ways to represent and understand human figures and the landscape and the relationship to light. And we don’t know what that is yet, but I think the new bodies and minds that we have in the spaces of the university today are going to figure that out, and it’s going to be incredible.”

Brandon Sánchez Mejia

Sánchez is one of these minds, coming up with new ways to portray bodies and creating a platform to spotlight people who aren’t always seen.

After Sánchez graduates in May, a month before his 30th birthday, he plans to apply for a Master of Fine Arts program in photography. He’s thinking of compiling a book of all his photos, and he has a “crazy dream” of working as a photographer for National Geographic, capturing the kinds of images that fascinated him as a child.

Last year, Sánchez traveled back to El Salvador to receive an award from the National Youth Institute — the Joven Destacado El Salvador 2023, or Outstanding Youth El Salvador 2023 — for his academic achievements. It’s an honor he never imagined getting. And in November, he became a U.S. citizen.

Even though his life in El Salvador can feel far away, Sánchez will never forget who he was or the things he went through.

“It’s part of my resilience,” he said, “and a reminder to be grateful and not take anything for granted.”

And, hopefully, he said, he’ll help others realize that they’re capable of so much more than they might believe.

See all photos from “A Masculine Vulnerability” and view more of Sánchez’s photography work on his website.

Learn more about UC Berkeley’s Department of Art Practice.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia