From UC Berkeley to 49ers sidelines, Harry Edwards dreams with his eyes wide open

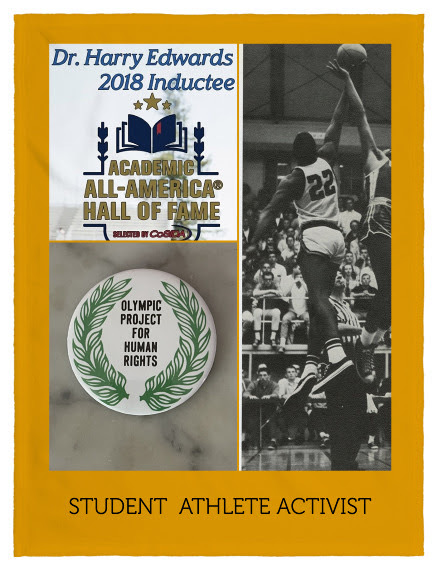

The UC Berkeley emeritus professor of sociology organized the 1968 Olympic Project for Human Rights. He's still influencing students, pro athletes and social justice.

Jed Jacobsohn via AP

February 20, 2024

In 1968, when Harry Edwards was working toward his sociology Ph.D. at Cornell University, he also witnessed the crescendo of one of the most politically violent eras since the Civil War. Racists and government authorities were gunning down prominent Black activists. Churches were being firebombed.

Society, Edwards sensed, was splintering.

Edwards had been an impressive collegiate athlete. But rather than pursuing a career playing professional sports, he committed to studying the social forces that shaped them. Sports, he observed, were a reflection of broader social issues involving race, gender, politics and power. But if athletics reflected society’s worst, he reasoned, it could also be a tool to make life better.

He knew he wanted to do more than study.

He wanted to take action.

LBJ Library via Wikimedia Commons

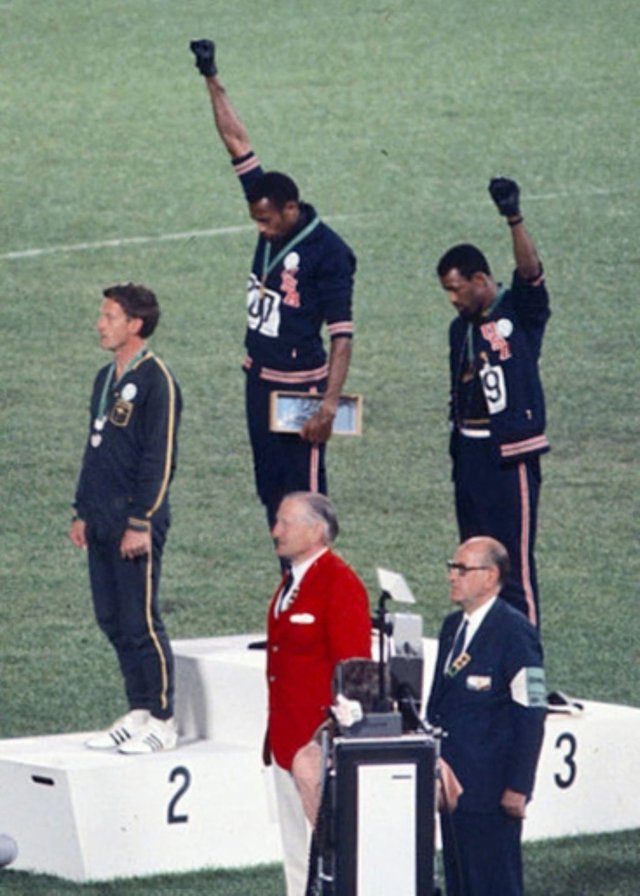

Edwards leveraged sport’s biggest stage — the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City — to protest rampant racial discrimination and advocate for human rights around the world. The Olympic Project for Human Rights he organized resulted in the iconic image of Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos — with bronze and gold medals draped around their necks — raising their fists while standing on the podium.

It was a pivotal moment in sports activism, emphasizing the power of athletes in the fight for justice and equality on a global stage.

Edwards’ activism and his work on what became the sociology of sport didn’t fade after the games. It blossomed. He began teaching at UC Berkeley, where hundreds of students jammed into lecture halls to hear him speak about how sport can hold a mirror to society — and how athletics can be used to shape the world.

Back then, activism by Edwards and others focused on broad, systemic injustices befitting the Olympic stage. More recently, he said, athlete-led activism has shifted toward localized actions that focus on and address specific aspects of racial injustice.

Wikimedia Commons

“Today, again, we’re entering into one of the most divided and one of the most politically tumultuous eras in the history of this country,” Edwards said. “The challenge is that the violence in society, more generally, is so great. … You could very easily lose focus in terms of those historic, race-related issues.

“And so we find many athletes who are saying, ‘Hey, we’ve gotta narrow our scope.'”

Edwards spent roughly 30 years teaching at Berkeley. Though his sociology of sport course was one of the most popular classes on campus, his career there wasn’t always rosy. Some leaders at Cal Athletics discouraged students from taking his course, he recalled. On the academic side, his rocky road to tenure spilled into news reports. That’s all water under the bridge now, he said this month: “I have nothing but the fondest of feelings for both of those departments.”

He went onto a successful consulting career advising college athletes and professional teams, including the Golden State Warriors and San Francisco 49ers.

Today, Edwards, age 81, remains an emeritus professor of sociology at Berkeley and worked recently with Cal Athletics. He was recently diagnosed with cancer, but he’s barely slowed down. This Friday, he, Smith and Carlos will reunite for a panel discussion on campus about social justice and the 1968 Olympic Project for Human Rights.

“It’s an honor for our Cal Athletics DEIBJ Office to bring Dr. Carlos, Dr. Smith and Dr. Edwards together with our campus community for this educational and celebratory experience,” said Ty-Ron Douglas, Associate Athletic Director for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Belonging and Justice. “These three scholar-athletes exemplify the brilliance within and power of athletics as a legitimate academic discipline and lever for social justice.”

Berkeley News spoke with Edwards about the evolution of activism and his enduring contribution to Berkeley, Bay Area sports — and beyond.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Berkeley News: Looking at today’s academic climate, what’s the biggest change in how people view the sociology of sport compared to when you were thinking about it 50 years ago?

Harry Edwards: The importance of the sociology of sport has only expanded exponentially with the complexity of the challenges that sport is involved with today.

I mean, we have officially embraced sports gambling at both the collegiate and the professional level. We have name, image and likeness money going to collegiate athletes.

We’re entering into one of the most divided and one of the most politically tumultuous eras in the history of this country.

Harry Edwards

We have this conference-jumping, which is in pursuit mostly of money, and the impact that travel has. I traveled for years with the 49ers. It got more and more difficult for me to recover when we were in the conference with Atlanta and New Orleans and so forth, flying across the country. I’m looking at that and wondering: What is going to be the impact on educational integrity, on the interests of the young people who are really what drives the game? What’s going to be the impact on them, health-wise?

Psychologically, we already have a burgeoning issue in terms of mental challenges facing modern collegiate athletes because of the pressures of participation, practice and preparation. What is going to happen when we have these cross-country conferences?

All of that makes the sociology of sport more germane and relevant today than it was in 1971, when I published my dissertation.

In that context, are there other social policies or even laws that you’re particularly concerned about affecting the rights of athletes?

I think we need to take a very, very serious look at the impact of the Supreme Court rescinding Roe v. Wade.

Roe v. Wade, in 1973, gave all of these institutions that set up and pursued women’s sports some assurance that if they gave a woman an athletic scholarship in May, she’d be around to start school in September and around to play in March Madness in March and for the NCAA finals in various sports in May and June.

Women’s sports have to be looked at with a greater degree of seriousness. I consider the rescinding of Roe, the assaults upon birth control pills and medical services for women, more generally, to be existential threats to women’s sports, particularly at the collegiate level. But even at the professional level in this country. We need to have a serious sociological analysis and look at that situation.

Kelly Sullivan via Cal Athletics

Do you think the policy around name, image and likeness (NIL) that allows athletes to be compensated goes far enough? Should players be compensated more for what they do for these institutions?

Courtesy of Harry Edwards

Nancy Skinner was one of my former students. She sat in my Sociology of Sport class as a student at Berkeley. Then she became a state senator in California, and she, along with Gavin Newsom, pushed through the NIL legislation.

Of course, once one state adopts NIL, every state has to open up to that. Otherwise, that state begins to siphon off all of the great athletes. Athletes are going to come to where they can get money. The NIL goes back to the sociology of sport at Berkeley.

If collegiate athletics cannot develop equitable, fair, enforceable and sustainable rules, regulations and so forth to govern, administer collegiate athletics in the interest of the only productive factors and forces in sports at that level — the athletes, then whatever organizations are there need to be dissolved and replaced by organizations that can.

It seems impossible to take away the role of politics and culture and sport at this moment. Look at the way some on the political right, for example, are focused on Travis Kelce and Taylor Swift and Bud Light boycotts and all these culture war issues. What do you make of this current moment in that context of culture and sport and society?

The same thing I’ve always made of it. Sport inevitably, unavoidably recapitulates society and the structural and dynamic institutional and human relationships involved, as well as the ideologies that rationalize and justify those relationships.

When I was coming up as a prospective college athlete, the only way that I could have gotten on the campus at the University of Florida or the University of Mississippi or Georgia, Alabama or what have you, would have been with a mop or a rake in my hand. Sport has always been embedded in the politics of the times. And that is something that is absolutely unavoidable.

You’ve talked about your legacy, which is something written about you, versus your contributions, which you’re more focused on now. What is your greatest contribution to this crossroads of athletics and academics in society?

Every generation — because this struggle is perpetual — has the challenge of making its contribution to restoring that effort to form that more perfect union. And so we must encourage young people, irrespective of the character of the times, to hold to their dreams, but that they must learn to dream with their eyes open.

Courtesy of Harry Edwards

I’ve tried to emphasize that any kind of struggle that is divorced from strategic analysis, research and intellectual consideration is nothing but a prelude to contradiction, conflict and probably failure. I’ve tried to capture what I think is important in a number of statements that will probably be repeated long after anybody remembers who initially made them.

Otherwise, I will simply settle for what people choose to research, even if it’s just a question of understanding that the John Carlos and Tommie Smith gesture produced the most iconic sports image of the 20th century in the eyes of many people around the world.

We’re still talking about it over half a century later and its impact and what it means and what it stands for, that when they go into it, they will see that this was something that was intimately related to the conditions that we found ourselves in during that five-year period between 1963 and 1968.

Something else that I’ve stated is it is never individuals but conditions that generate protest, revolt and efforts at change. And so those are the kinds of things that I hope will stand out, that people will remember.

One piece of advice you often give to young people is to “follow your bliss.” As someone who has navigated big institutions — from the Golden State Warriors to the San Francisco 49ers to Berkeley — do you have advice for young people trying to follow their bliss in big institutions?

Courtesy of San Jose State University Library Special Collections & Archives

Yes, “follow your bliss” comes from my blueprint for educational achievement. Students can take a look at that as an intellectual strategic analysis that links your efforts in education and activism to your life. It’s all one seamless fabric.

If you want to be a great football player, you can’t say, “I want to be happy on Sunday” and put on a uniform, but not want to take any hits. You understand the demands. Every Super Bowl team or championship team I’ve ever been associated with prepared and was focused long before they won a championship.

You don’t work up to become a champion. You behave and perform like a champion.

So you have to learn to behave as if I’m going to have to take advantage of the only demonstrable, proven shortcut — whether in academics, athletics or in life — which is hard work. Everything else is more difficult. Hard work is the shortcut. Understand that tomorrow you will be exactly and precisely what you achieved today. And so you have to be conscientious in that effort and persevere.

That would be the advice that I would give to students today who are wondering how to follow their bliss. That is something that I had to figure out over half a century ago.

And for many of my students, it has worked.

Courtesy of Harry Edwards

And when you think about all of those Berkeley students you have advised over the years, that you have inspired, how does it make you feel?

I fell in love with every team that I ever consulted with at the professional and collegiate level. I fell in love with every class that I ever taught at Berkeley. People say, “Well, you got 550 people in that class. You don’t even know who’s there.” I fell in love with everyone. And there’d be this little entourage of 30 or 40 students following me the whole way back to the office: “Can I ask you one more question Dr. Edwards?” They just loved to ask me questions and hold the conversation.

So I fell in love with every class I ever taught at Berkeley. And when I look back at the experiences that I’ve had, the things that I’ve tried to do — not always successfully — but the contributions I’ve tried to make, I’m doing better than I deserve.