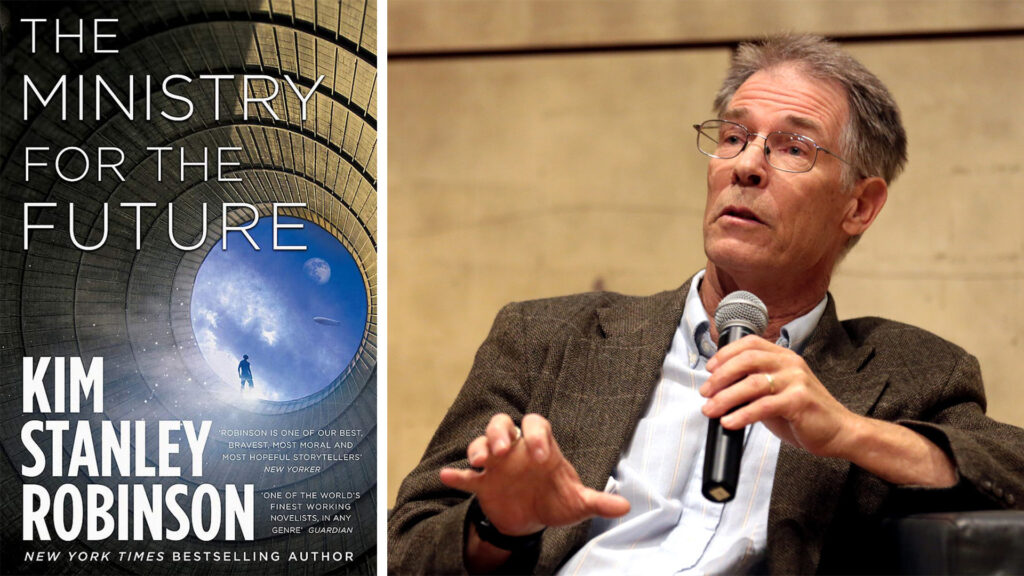

Berkeley Talks: Sci-fi writer Kim Stanley Robinson on the need for ‘angry optimism’

March 22, 2024

Follow Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. See all Berkeley Talks.

Gage Skidmore via Flickr

In Berkeley Talks episode 193, science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson discusses climate change, politics and the need for “angry optimism.” Robinson is the author of 22 novels, including his most recent, The Ministry for the Future, published in 2020.

“It’s a fighting position — angry optimism — and you need it,” he said at a UC Berkeley event in January, in conversation with English professor Katherine Snyder and Daniel Aldana Cohen, assistant professor of sociology and director of the Sociospatial Climate Collaborative.

“A couple of days ago, somebody talked about The Ministry for the Future being a pedagogy of hope. And I was thinking, ‘Oh, that’s nice.’ Not just, why should you hope? Because you need to — to stay alive and all these other reasons you need hope. But also, it’s strategically useful.

“And then, how to hope in the situation that we’re in, which is filled with dread and filled with people fighting with wicked strength to wreck the earth and human chances in it.

“The political battle is not going to be everybody coming together and going, ‘Oh, my gosh, we’ve got a problem, let’s solve it.’ It’s more like some people saying, ‘Oh, my gosh, we’ve got a problem that we have to solve,’ and other people going, ‘No, we don’t have a problem.’

“They’ll say that right down over the cliff. They’ll be falling to their death going, ‘No problem here because I’m going to heaven and you’re not,’ or whatever. Nobody will ever admit they’re wrong. They will die. And then the next generation will have a new structure of feeling.

“In the meantime, how to keep your hope going, how to put it to use … I think all novels have a little of this, and then Ministry is just more explicit.”

This Jan. 24 event was sponsored by the Berkeley Climate Change Network and co-sponsored by Berkeley Journalism; Berkeley Center for Interdisciplinary Critical Inquiry, home to the Environmental Arts and Humanities Initiative; and the Townsend Center for the Humanities.

Intro: This is Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can follow Berkeley Talks wherever you listen to your podcasts. New episodes come out every other Friday. Also, we have another podcast, Berkeley Voices, that shares stories of people at UC Berkeley and the work that they do on and off campus.

[Music fades out]

David Ackerly: In many ways, this is an inaugural event for the Berkeley Climate Change Network. Many of you know that the network has been providing a backbone of communications about all things climate, sustainability, and environment, especially climate, over the last couple of years. And I want to thank Carl Blumstein whose institute, California Institute for Energy and Environment, trying to get that ecology in there. It really is the host for the network, David, and I co-sponsor it.

But most importantly, Bruce Riordan, who many of you know who’s the heart of making the network work. Bruce is at home with an undisclosed medical ailment that starts with C and ends with D and has five letters. So really, really sad. He put out heart and soul, he was so excited about today’s event, and had really helped to build our contacts with our guest speakers. So huge thanks to Bruce and we’re very sorry he’s not here today.

The other co-sponsors of today’s event, the Berkeley School of Journalism, Jason Spingarn-Koff. Yeah, give it up for journalism! Jason, the Berkeley Center for Interdisciplinary Critical Inquiry, which houses the Environmental Arts and Humanities Initiative. And Debarati Sanyal is the director. Debarati, thank you. And the Townsend Center for the Humanities at Berkeley, Stephen Michael Best. Where’d you go, Stephen? There you are, Stephen, is the director.

And for those of you who don’t know, the Environmental Arts and Humanities Initiative really was a spontaneous, a good Berkeley thing where faculty and graduate students and others who shared an interest came together and started a mailing list and it’s just been percolating to bring together. And I think for many of you who, if you’ve come from other universities, other campuses, know that that intersection of environment and the humanities is absolutely essential to our collective future telling the stories of our future. And this is a wonderful event to bring those two together as maybe a down payment on many such future events. So we’re really thrilled.

I do want to give also a quick thank you to Tiff Dressen from the VCRO’s office, Cassie, Sarvesh, Miriam, JD and Dong, who are all the volunteers who checked you in and helped organize. So thank you all for all your work to make today possible.

[Applause]

There is a lot going on at Berkeley and sometimes we’re famous for not being able to tell our story well and pull it all together. But we know inside that we are doing just incredible work to address the looming climate crisis, to have our research, our teaching, and our service to the world have the most possible impact we can at a critical moment.

I’m especially excited that Rausser College just announced a new Master of Climate Solutions, a professional degree that will also have a concurrent option for students getting an MBA. So a new collaboration with Haas and … A lot of constituencies here today. I like it. I love it. I mean, that is the excitement. There’s so many different audiences here. This is really cool. I mean, we often talk to our own audiences, but this is so much fun to have people from so many walks of campus and off campus. I know from looking over the list of who’s here.

Our first new college, College of Computing, Data Science, and Society, doing a lot of work, investing in the role of AI, and looking at sustainability issues, new materials, the discovery of just the fundamental research that can drive some new discoveries for sustainability. We had an exciting cluster hire three years ago. Many of you know Climate Equity and Environmental Justice brought five young scholars to campus who really have become a nucleus of an incredible community and the work on environmental justice is central to, really the core identity of what Berkeley does in all areas of inquiry.

This semester alone, we’ve counted more than 50 climate-related classes on campus. There is a database, it’s a little obscure to find, of all those classes, but one effort is to make those more visible to undergrads who are seeking for curriculum in this area. And I know there are other exciting announcements coming later in the semester, so just keep an eye on more going on around climate and sustainability. And we really, and at the core of so much of this, I think all of you know that especially the core of creative, interdisciplinary novel engagement is building relationships. So events like this are absolutely essential. So the reception afterward is required, if you’ve come to the talk. If you have to go, of course, you have to go.

But on that note, our plan is about 60 minutes of dialogue among our, I’ll introduce all the speakers in a moment, about 30 minutes for Q&A, and we look forward to all of your questions. And then we will head out to the lobby for a reception and you’re all invited.

So it is a pleasure to introduce a distinguished guest and speaker today, Kim Stanley Robinson, who is seated to my right, has published 22 novels and numerous short stories over four decades of work. He is perhaps best known for his Mars trilogy and now for Ministry for the Future. His work has been translated into 24 languages. He has won numerous awards including the Hugo Award for Best Novel, the Nebula Award for Best Novel, and the World Fantasy Award. We hope that everything in Ministry for the Future is not fantasy. We hope some of it might be fantasy, but not all of it, hopefully.

The Atlantic has called Robinson’s work the gold standard of realistic and highly literary science fiction writing. There’s a quip, a favorite quip I have from a climate scientist who says, “What we really need at this moment is more data from the future.” Unfortunately, at this time, these data are not available. So the closest we have is … The future is fiction at some level because it’s unwritten. And I think this is what’s so fascinating about the creative process of trying to envision and imagine collectively what that might look like.

The New Yorker has said Robinson is generally acknowledged as one of the greatest living science fiction writers. His latest book is a change of pace, The High Sierra: A Love Story, sharing many stories from his lifelong love of California’s Sierra of Nevada Mountains.

Leading the conversation today will be two Berkeley professors with great interest in both the climate crisis and the art of writing. Daniel Aldana Cohen is assistant professor of sociology. He works at the intersection of the climate emergency, housing, political economy, social movements, and inequalities of race and class. And Daniel is the director of the Sociospatial Climate Collaborative.

And Katherine Snyder is associate professor and director of the Berkeley Connect Program in English. Over the past several years, Katherine has turned her research and teaching to contemporary fiction with a particular interest in post-apocalyptic, post-traumatic, and post-9/11 novels. Recently she led a research seminar on climate change fiction, which is now cli-fi if you haven’t heard that yet, we now have the genre of cli-fi. You shouldn’t laugh. No, sorry. You shouldn’t laugh because that’s what we’re here to talk about. So please welcome Katherine Snyder, Daniel Aldana Cohen and Kim Stanley Robinson.

Daniel Aldana Cohen: OK, I think we’re on. Thank you all for coming out today. So nice to be here full of people. The whole auditorium is a red carpet, so it also makes us all feel glamorous. Stan, it’s really great to be in conversation here with you. And thank you for letting us dwell on your second last book, Ministry for the Future, which is basically a phenomenon all on its own in climate politics. It imagines the next several decades of climate politics. And so even though it’s been a few years now, the prophetic and the sci-fi has worked, and this remains an essential touchdown for climate thinking and climate action today.

Climate politics are my favorite topic, so I’m going to be asking questions about those. Katie, who’s an expert in sci-fi and cli-fi will dig in on that element of the work. To start, I want to ground us a bit in the gravity of how existential a threat climate breakdown is. In Ministry, you use a few different narrative frameworks for this.

The book opens famously with a harrowing scene of a heat wave that kills in the neighborhood of 20 million people in India. On the last page of Ministry, you emphasize a different register. You write that the only catastrophe that can’t be undone is extinction. So there’s an emphasis on genocide and there’s an emphasis on ecocide.

So it’s been a few years since you wrote this book, and I’m curious, when you try to convey the climate emergency viscerally to people now, what scene do you set and what scene does your unconscious set for you?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, thank you for that, Daniel, and I won’t go on in too much length because I feel like everybody knows the situation that we’re in, and I don’t need to reiterate it to a knowledgeable audience. When I spoke at the end of Ministry about an extinction event, I don’t mean human extinction. That’s not what’s going to happen. It’s a mass extinction event, the sixth great mass extinction event in Earth’s history. The first one that’s anthropogenic.

A few humans will crawl out of that alive like we did 73,000 years ago when there were only about 2,500 humans left after what was probably a big volcanic explosion and a volcanic nuclear winter. Most of them were on the coast of South Africa eating clams and tubers for 10 years or more. And then we recolonized the world from that event. That would happen again no matter what we do, probably. And the humanity part of it is not as important to me as the mass extinction event of thousands of species going under. And that’s what we could never recover from.

The earth is robust, life is robust, humanity is powerful and clever. But when we drive other species to extinction, the de-extinction movement is not quite a party exercise, but it’s a demonstration project to teach us more about what we could do or can’t do. We’re not going to de-extinct the many species that we’re driving to extinction, and nobody should be fooled by that, even if we bring back some weird version of the mastodon or the passenger pigeon.

But you ask, what do I think of as a disaster now? And it’s worth saying that I’m much more sanguine about our coping with climate change than I was when I wrote Ministry for the Future in 2019. It was a darker time than the now, which is a good thing to report. And I want to say my most recent book, the High Sierra book, just as a little aside before we go on, I want to thank Roger Bales is here, UC Merced’s Sierra Nevada Research Institute on which I’ve been on the board of advisors and you know how crucial board of advisors are. But I’ve always put that on my resume of the things that I’ve done in the world. I’m an advisor to the Sierra Nevada Research Institute and I’m proud of it. And I love the Sierra, and that’s one of the things that’s terrified me.

I think of a world where the High Sierras are one of those blasted mountain ranges in the Basin and Range, like Nevada, that would be sad. And I also think in terms of catastrophes and the terrible danger that we’re in, you remember in the COVID there was a panic over toilet paper and a run on goods like that. If there’s ever a panic about food supplies then social breakdown could quickly follow and starvation could quickly follow that. We are in a brittle system and it relies on social trust, which is getting a little bit shook. At least it looks like that in the media.

So when I imagine things going wrong, I imagine them slipping under the radar and being a little unobtrusive, and then a tumbling cascade effect to a panic. And if it’s a food panic, we could be screwed.

Katherine Snyder: It makes me think about that quip about things getting bad gradually and then all at once, which sounds like what you’re describing. So what I’d like to begin with is by observing that the very idea of a ministry for the future is a really striking premise. It’s a very science-fictional conceit, and it suggests new ways of thinking about time and thinking about change. And for one thing, it suggests that the future is not just a historical moment or a period, but a common good or even a right.

And the book brings into focus, for example, the idea that future humans have rights, and this idea resonates with a growing number of actual climate-related constitutional cases and federal lawsuits that have been filed by or on behalf of children. And I would say… Well, I can follow up with this but just I’d like to ask you to talk about how you understand the future as a resource.

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, it’s a strange way to put it, but on the other hand, let’s follow that. The future is mortgaged. The future is bought and owned. It’s part of capital investment. And so after capitalism has taken over everything, the natural world, the rest of the nations on earth, and then begins to invade the unconscious mind through the dream factory and also the natural world, etc. Everything is bought and sold, everything capitalized and becomes capital, then the future is a space for investment.

And so you have your mortgage, and indeed the future is entailed in mortgage and there’s even path dependency. These things need to happen to capitalism, it will keep capitalism going because we’ve already agreed to it in contractual terms, legal and contractual terms. So if the future was a commons, then there’s also enclosure. And anywhere there’s a commons, there’s an enclosure movement trying to privatize it and take it over for profit. This is my reading of it, and I think it explains a lot.

So if you are fighting to liberate the future and return it to a commons and say it’s a public good, then you have to look at things like the discount rate and the nature of contracts. And are there rights, legal rights for future humans or for we in our futures? And also the children, these children’s trust are a wedge in. And here I’m thinking about environmental ethics and law. Christopher Stone’s Do Trees Have Standing? And then my wonderful colleague, Chris McKay, wrote a book called Do Rocks Have Standing? Because this was a question on Mars, do trees have standing?

So what was argued by I think Stone, was that over time, more and more humans have been made fully human in their legal rights. So at first, it was men and there were slaves and there were children and there were women, and none of them had rights like a certain privilege. And the expansion of that umbrella of rights to more and more people until a moment came where it’s asserted that everybody should have equal human rights. And you could point to things, the UN declaration in ’45 or whatever, but also the legal regimes until it spreads out, and out, and out.

Well, as an expansion from children’s rights, shouldn’t future children have rights? And then the future comes into play and we discount the future economically with a discount rate. Nordhaus got the pseudo-Nobel in economics for saying the discount rate can be 4%, and that treats future generations well, this is wrong. The discount rate should be zero, as some economists have said, or it should be in some strange fluctuating starting at zero and going up to three over 500 years. The economists need to play that game to properly financially rate the future generations relative to our own efforts right now.

And so in many ways, talking about the future is a contested space and it teaches us what should we do right now as part of our political program because we’re not just protecting ourselves and our loved ones and our immediate living children, but also the generations to come. And I want to add the ministry for the future, I was at a conference in Barcelona, beautiful event they have every year. It’s a pan-European cultural thing that the Catalan government in Barcelona puts on. And the museum curators there had the philosopher, an old friend of mine from UC Davis, Timothy Morton, and they had designated him the Minister for the Future for this one conference.

And I was thinking, “Oh, that’s why I can’t understand him. He’s from the future.” And it makes him pretty incomprehensible, I would say. Although a lovely guy with great ideas. And then as they were interviewing me, these Catalans said, “You should write a book about a Ministry for the Future.” This is 2017. I said, “Good idea.”

Daniel Aldana Cohen: All right, next year in Barcelona, I need a good book idea. OK. So I want to circle back and we’re in some crazy spiral here, but something you said a minute ago, which is the difference between where we are today and where you were when you wrote Ministry back in 2019.

In Ministry, I think the 2020s are a lost decade, and I want to honor that for some that’s starting to feel that way now. We have the possibility that Trump could get reelected. The authoritarian right seems strong all over the world. There is a lot of bad stuff happening. Many of us see what’s happening in Palestine as a genocide.

There’s a lot that’s bad that’s happening. And the U.S. is such a chaotic and powerful empire that it can do horrible things with one hand and other things with a different one. So at the same time as all this is happening, we have the Inflation Reduction Act, which for all its flaws, moves a lot of money into the green economy. We have the arrival of green capitalism very clearly, full of power, full of contradictions. So I’m curious where you see the fights for climate progress and for human decency today in ’24?

What are the big opportunities for the rest of the decade? And [inaudible] question the Global South is so essential in Ministry. The big saviors really come from India after a left turn and China. Where do you see the Global South right now as an actor in climate politics?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, that’s a very important, but let me run backward to the, I’ll make my answer in the sequence of the questions and try to go back and assert that things were much more dire in 2019 than they are now and why I think that. I wrote this book in … I was much angrier and more fearful because I don’t think we had yet really begun to move on climate change. It wasn’t felt as a reality and Trump was still president and it wasn’t at all certain that he would lose in 2020. And I wrote it in 2019 when the media was cranking up the soap opera just like they are right now. That’s another topic though, the soap opera of presidential politics. But let me not get diverted like we always do.

So I had sentences in Ministry for the Future like, “The 2030s were zombie years.” And I stretched out the whole process of dealing with climate change until a COP that is, if you run the numbers and dates, I didn’t want to give a date to it, but I wanted it to be datable if you wanted. It was like 2058 or something. So three decades, it’s not several decades, it’s just three. But that’s Mary Murphy’s career. And that’s the shape of the novel.

Well, the pandemic, it was a slap in the face. Everybody realized, “Oh my gosh, the biosphere can kill me. And not only that, but when the biosphere is sick, I can be sick and my life as a social primate can be disrupted like that. And the health of the biosphere is intimately connected to my own health and climate change is part of that. It’s a fever that the biosphere has. It means I too, have a fever.” And although we haven’t sorted out the pandemic, and it might take a long time and maybe only historians will do it, I feel a huge difference between pre-pandemic and during and post.

And people had a lot of time to read during the pandemic, they’re reading Ministry for the Future and they were reading it thinking, “Oh yeah, this could happen.” So the reception of my book, which I thought was going to be rendered irrelevant by the pandemic because it’s not in the book because it wasn’t happening when I wrote the book, instead it made it like a needle in your eyeball. And we’ve all come out of that experience shattered. And the 2020s are the zombie years were exactly the 20-teens or the whole of the 21st century until the pandemic. Those were the zombie years. And science fiction is often about the present. This is not a particularly unusual accident to make.

The 2020s are actually filled with ferment disorder and intensity in a way that’s actually good for us. So that’s what I wanted to say about that, that I’m seeing action. You mentioned green capitalism. I am an anti-capitalist. I guess it’s OK because, hell, we’re in Berkeley. I could say I am an eco-socialist, but I don’t want to. As a novelist, I’m already way out there on a limb politically as far as pushing my characters around as if they’re tokens of political ideas. That’s fine, novels always do that. But as an eco-socialist, I have to say this, we’re in a capitalist world and we’re in the nation-state system and we’re in a climate emergency.

There’s too much CO₂ in the atmosphere. We’re going to have to draw down CO₂ from the atmosphere. We’re in a CO₂ overshoot. You can draw down CO₂ by natural means. And it’s not the only thing we have to do because we have to cut emissions also. But over the next several decades, we’re going to have to get back down to something like 350 parts per million. Part of the genius of McKibben’s organization’s name is that that’s a good number, 350 parts per million of CO₂. So that’s going to take decades and it’s going to take natural means, reforestation, re-wilding, it’s good stuff, regenerative agriculture.

It’s good processes that will draw the carbon back down out of the atmosphere and get us out of danger. So in all of that, the Global South is crucial to get to the end, India in particular. China’s not a big player in my Ministry for the Future novel. I had just written a novel about China and it completely kicked my butt and I crawled out of that one and wrote Ministry instead. So China does not play a big part. I can refer you to my novel Red Moon, which was going to be called China Moon until my editor got scared, for my China thoughts. But India is crucial. India is the biggest democracy, it’s now got the biggest population. We’re sitting right there on the equator more or less, and it is dynamic.

Now, oh my gosh, does it have a problem with a right-wing authoritarian government? Well, lots of countries do, but sometimes they have them for a while, like in Brazil, and then an election happens and those guys get kicked out. So the Global South is in play, and so is the whole world when it comes to do you go to the right and dig into your national hole and say, “I’m just going to concentrate on my nation and the rest of the world can go hang.” Or do you become international and say, “Look, it’s one planet, it’s one people. We got to cooperate together.” That political battle is the battle of our time and it’ll happen in every country.

So I also want to say that having put a climate disaster that kills millions in India, I felt obliged to India. I needed to stay there. I needed it to be the solution and not just an excuse for an American to put the problems on the other side of the world and then we solve them. I needed Indians involved in solving it. They are in huge danger from a wet bulb event, although one of the hottest wet bulb events ever recorded was outside of Chicago.

So it isn’t like we’re not in danger, but India’s in real danger. I mean more present, more immediate. And I wanted to stick with them. And the book has been well-received in India. I mean, aside from the occasional hate mail from BJP party nationalists, but by and large, the Indians have said to this book, “Oh yes, Farhanji is finally understood. We are the center of the story and we’re going to solve the problem here.”

And of course, every big country has horrible difficulties right now, but the potential there for solutions and for action in the world is gigantic.

Daniel Aldana Cohen: Thanks so much. There’s so much here to pick up on, and I’m thrilled every time you talk about yourself as an eco-socialist — that’s my spot. I’m like, “It’s not just me. I’ve got friends.” You’ve taken on a bunch of things I was going to ask at once, so I’m going to do an audible here a little bit. There’s a phrase by Pierre Bourdieu, a sociologist, like me. He says, “sociology is a combat sport.” And in a way, I think your science fiction is a combat sport. And what I mean is I think you’re, if not helping, at least talking through different ways that different people in different arenas do the climate fight.

It seems very strong from your work that climate politics is a fight, it’s a struggle. Now I get the 2019 was more of a … Maybe felt harder than it does now, but you have scientists battling within science, you have organizers battling within organizing, etc. And I think there’s even a bigger picture story that you got to just now, which is there’s a broad, let’s say progressive, progressive center-left block. And part of I think what you’ve been saying is to your friends on the left, you have to have a certain degree of pragmatism to take on certain elements of climate.

And so I guess what I’m wondering here is where do you see the prime areas for combat, for struggle in climate and how do you think different segments of this broad spectrum of actors need to struggle in different ways. Whether it’s by any means necessary of the black wing, whether it’s fighting over resources at the National Science Foundation, whether it’s engaging in global diplomacy. How do you see that set of fights and how do you see them interconnected?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, I want to start with the notion that the front is broad. And this is an old leftist slogan that gets routinely ignored as people on the left slaughter each other because they’re the only ones listening to them. And so the destruction of the left by the left is notorious. So when you say the front is broad, it’s aspirational saying, “Look, you’re going to be working with a mixed ideology group. You’re going to be working with people you don’t agree with and certain other aspects, but you’re on the same front battling the same fight, you’re allies,” and not be too pure about it. And then with that notion in mind, you have to pick what your passion is and follow that.

And there’s local things that everybody can do now. Easy in Berkeley, but I’m thinking every town bigger than 20,000 people on Earth has a climate action group or a nature reserve or something that they’re protecting locally and it works up from there. You do need, especially in a two-party state like we’re in here, you need the left party in control to pass progressive legislation including progressive taxation. That would probably include a carbon tax, that would be so smart, but also incentives so that there would be carrots as well as sticks.

So in my novel, it’s called the carbon coin, but I want to say that the carbon coin in my novel is just one small example, maybe even symbolic of a whole raft of financial instruments that are out there available for what you might call priming the pump or public money or Keynesian politics or government takeover of the economy for the salvation of the world and a World War II mode. All these are different aspects of things that could be done to make sure that we get paid for doing green work, that you can make your living at it. Not a virtuous thing you do on the side or a saintly thing that you do and suffer for, but a way to make a living, and a way to have a career, to do green work.

And that requires … Standard, especially neoliberal capitalism is not about that at all. That was all about the highest rate of return and the highest rate of return was set poorly so that if you destroyed a forest and sold it, the cash you got for that would be worth more than holding on to that forest. And these are the kinds of economic calculations that are routine in neoliberalism and still taught in business schools and, of course, slashing labor costs, which if you translate these things into English terminology like Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary, cutting labor costs, well, we make people suffer.

The right rate of unemployment. Well, we make people scared. You wouldn’t want full employment because you wouldn’t have people scared enough. So standard, ordinary neoliberal capitalism is designed to make everybody in the precariat and a certain percentage of people immiserated to scare the rest into taking their shitty jobs. So this is all … I won’t go on longer because I believe this is standard boilerplate in Berkeley and in this crowd.

Daniel Aldana Cohen: Here we go. OK, thank you for repping Berkeley Social Science, we’re trying. We’re also at a university with a lot of scientists. Let me ask you a question about science. You’ve talked about the idea that the world is defined by this Manichean struggle between science and capitalism. And I think that resonates with a lot of folks, and I think for others it’s a bit of a confusing way to frame it.

There are, if we take something like carbon drawdown, which you mentioned earlier, there’s a core science to it and I think it’s probably really good science. Then you have a difference, of course, between the oil companies like Occidental who want to use that to then do enhanced oil recovery versus a vision of carbon drawdown as a form of climate reparations with the Global South. And so for a lot of movements of color, for a lot of indigenous nations, I think for them they see elements of science that they’re interested in, elements that they’re not, but it’s much less clear that it’s a Manichean struggle and feels much more complex.

I’m curious about a couple of things, where you see science today in all of this, and I’m also curious what you see as some of the most exciting developments in the world of science, in the struggle to make science more of a project of human discovery and less of a project of profits. A struggle you depict a bit of, I think in your Green Earth books, but let me just open up to where you see some of these fault lines in science today and where it could be going.

Kim Stanley Robinson: Yeah, sure. It’s important. I have been saying for decades now that it’s science versus capitalism. And this is a little confusing because they were born together and they’re like conjoined twins. And I wrote a novel about Galileo to try to think about the beginnings of these things. And there’s a sentence from there that keeps coming back to me. Science was born with a gun to its head. It was there for military purposes, to improve military weapons, Galileo’s main clients, the Venetian Senate, and to a lesser extent the Medicis. He was a military engineer first and then became an astronomer, etc.

So science has always existed since the Paleolithic trial and error and then mathematization and experiments. The scientific method is usually powerful, and it was, I believe, there to make less human suffering and a more secure life for human beings. It was anthropocentric for sure, but it was trying to do good in the world. That was the origins of science. Capitalism is a liquidified feudalism. It’s a power relation. It’s the few over the many and extraction, appropriation, and imperialism. Now listen, I’m just talking at the level of sock puppets or Hindu mythic figures, but you see what I mean.

If science wins, the scientific thing would do would be to have everybody living in adequacy and more or less in a trusting relationship with each other. That might’ve been true in the Paleolithic or when we were pre-Homo Sapiens. But in any case, could be made true. And in that battle then capitalism is saying: “No, but we own you. We’re still the ones paying for it. Your science is done for us.” The battle is perpetual.

So when you see, especially the UCs, when we turn them from public into privatized, when the UCs went from getting 80% of the budget from the people of California down to 7% and had to beg for money or sell themselves, sell their work, then the science departments became way prominent because you can sell scientific tech transfer developments in a way that you can’t really your humanities results.

So the sciences get more powerful because they’re making stuff that can be turned into money in the bank. And this is that verb innovate, which you hear all the time, right? Innovate. This is another devil’s dictionary thing. What that means is invent with the patent and you should just be inventing.

So what can UC scientists do? I have a friend, a rice scientist out at UC Davis, Pam Ronald. She has used CRISPR to make rice that can stay drowned for two months instead of two weeks, and she immediately open-sourced it. And there are about 5 million acres in Bangladesh and the Philippines that just took her rice and planted it, and it was open source, and nobody profits from it. And this is what could be done all across the board.

If the UC President’s Office was interested in education and the welfare of the world as opposed to making enough money to run their business, then they would require open source for all of their scientific discoveries and not allow individual scientists or the university to privatize the knowledge that will then make the money. It should be again; this is again the commons versus enclosure. And to see the UC system enclosed, and I’m a UC graduate, UC San Diego, UC as a totality is the greatest university on earth. To see it go from public to a private money-grubbing, let’s make some people rich and the rest of them, everybody talks about Berkeley, UC Berkeley as basically being a big real estate company.

Education is secondary to the real estate because they want to make money. This is the knock against it. I would push back against that, say, “Actually the English department at UC Berkeley is very fine and it has little to do with real estate.” But the battle is there, too, right? The university is a space of contestation.

Daniel Aldana Cohen: All right, I’ll ask one last quick question. I really appreciate you saying that.

Katherine Snyder: Me too.

Daniel Aldana Cohen: OK, so there’s a lot in Ministry about this enormous infrastructure that gets changed in order to have climate action. There’s also quite a bit, but I think it’s rendered in a slightly different way about the infrastructure of everyday life and how it changes. And so the story of Mary Murphy, who’s basically like a global savior but lives her life in one-bedroom apartments, very happily travels around by train, takes rail to go hiking in nature, is a really interesting story about what a good life looks like, where low-carbon leisure and social efficiency happen.

And the Zurich in which that occurs is also shown to have an incremental struggle, but in the characteristic way, progressive struggle toward incorporating migrants from elsewhere in the world.

So I wonder if you could just say a bit, how do you think about climate change changing the social and physical infrastructure of the good life, and where does that rest in your narrative and your vision?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, it would be nice to think of climate change as the emergency that forces us into a better imagination of our collective life together just by the spur of an emergency. My parents’ generation, the World War II generation, they spoke with great fondness of the war. Well, this is a terrible war. And of course in America, it wasn’t as deathly as everywhere else, but a sense of solidarity that the whole society was on the same page and there weren’t actually billionaires. There was progressive taxation from the New Deal that somehow the New Deal in democracy had defeated the rights and forces of darkness and then everybody’s on the same team.

Wow, doesn’t happen now. But wonder if climate change dealt with correctly might bring back some of that feeling. And climate equity is very important in that phrase that since we have this history of imperialism and of rich and poor and of colonization, and colonization didn’t quite go away but rather got financialized. So the World Bank, the post-World War II order, the United States as empire with 800 military bases around the world, and with the U.S. dollar as the benchmark monetary unit on the planet is really in control. 5% of the world’s population, 75% of the capital.

Well, this is weird and unsustainable. And in the Paris Agreement, we signed with everybody else, there shall be climate equity. That the advanced nations, having burned more carbon, need to help the less advanced, developing nations, the poorer nations monetarily, to get themselves into the clean transition faster so that they jump past fossil fuels where there are a lot of places not even electrified, don’t have clean water, don’t have toilets, that you jump quickly to the clean energy that will allow everybody to be at adequacy.

That might create a solidarity. And I’m fully in favor of a progressive taxation that would make being a billionaire impossible, that the tax rate would be progressive enough that when you got to your, I’ve talked about this in Silicon Valley, what would be the number? I got people to agree that once you got to 10 million, you and your kids are probably OK. And then I pointed out that that was 1% of how much money they had. So that you had $990 million left over after you’ve got your 10 million that should really belong to the people and be part of the school system, etc.

And also because I’m a science fiction writer and live near Silicon Valley, I’ve met any number of billionaires and they’re all men. That’s a sign something’s wrong. But also, also, they are not happy people. They’ve got too much, and they call it the “Midas Touch.” Everything they touch turns to gold, like with Midas, they can’t trust anybody. They’ve got bodyguards. Their love lives are a mess because who can they trust? When you’re a billionaire, you’ve made yourself inhuman. It’s not that you’ve turned into gold, it’s that everything else turns into gold. So one advantage of taxing billionaires out of existence would be a lot happier rich people because …

Katherine Snyder: I’m going to turn our conversation now to … I forgot, is it on?

Daniel Aldana Cohen: Yes.

Katherine Snyder: Yay. So I’m going to turn our conversation now to more to the literary, although we’ve been talking about some of how one represents these characters and their struggles as well as the arc of a character like Mary. So far, I think all of your comments and many of your questions have highlighted the massive scale and complexity of what it will take to fight the climate change, and as you said, on many different fronts. And just thinking about climate change itself and about the Anthropocene as a geological era, it requires us to wrap our minds around something that’s just unimaginably huge.

It’s an inhuman scale of time and space. Enter science fiction, and you’ve always been a pretty maximalist writer, Stan, but do you feel that you’ve taken on new or different structural forms or narrative devices in your recent fiction, and particularly in Ministry for the Future, in order to represent the scale and the complexity of our environmental challenges? Or is climate change and our struggle, our fight to manage it just terraforming, as usual, part of a longer tradition? And so what have you had to do to imagine differently in terms of the forms of your fiction?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, thank you for that, Katie, because I’d love to be talking about the novel as a form and a craft, and indeed get away from a policy in climate and science and just be an English major again. Which is what I was and what I still am, still reading novels with immense joy. It’s a big part of my life and it’s what I do. So there is a form problem, and I’m glad you brought it up. Science fiction is designed to represent humans as types, like in H. G. Wells’s time travel, The Time Machine, where it’s the time traveler, the journalist. They’re just not even given names and that was a smart thing to do.

The relationship between the individual and the other individuals, which is the realm of literary fiction or domestic realism, and then also the relationship between that individual and their historical moment. That’s the social novel, I quite love it. I’m thinking of Balzac, George Eliot, the 19th-century social novel, and then the relationship to their planet. And that’s where science fiction came in, especially the planetary romances of the ’50s, which came to its flowering and greatest point with Ursula K. Le Guin’s first four novels, Planetary Romances. What’s the relationship between humans and their planet?

Well, science fiction is already designed to do it, and now we need to tell that story because now that we know about the gut microbiome, 50% of the DNA in your body is not human DNA. We are creatures of this planet and we’re co-evolved with it and coterminous with it. And telling that story means you need science fiction. Great, I love it.

But there’s still form problems. A novel still goes back to characters in a plot. I love that. I think it’s important. The imaginative act of reading a novel is as a case of imagining the other. Now I am the other by a case of teleportation and time travel. These are science fictional skills that reading novels take part and it’s beautiful and it’s a generous act on the part of readers and an imaginative act.

Black marks on the page, “Oh my God, I’m a 5-year-old girl in Naples and it’s 1945.” Or, “I’m in a sea battle against Napoleon’s Navy and we’re running out of cannonballs.” You have these experiences and you come back out of them. So you need characters and plot. You can’t be so experimental that you suddenly shade off into nonfiction. “I, the earth, tell you this story.” But if you stick to characters in a plot, you can see this in my DC novel called Green Earth now. Enormously long small characters, one city, and I have not managed to come to grips with climate change.

And I put five years into that trilogy, and between Washington DC and climate change and foreign problems, I crawled out of that one thinking, “OK, I better try something different next time. That didn’t work.” And so this is where being an English major and thinking about form, there’s the it-narrative of the 18th century where a coin or a violin tells you its story. There’s the riddles from Anglo-Saxon, one-third of Anglo-Saxon written literature left to us is just in the form of riddles without the answers. And so scholars argue, was that a grasshopper or an angel?

And of course, the answer to the riddle is often a pun, often a sexual pun. And then the thing that got me because I have several more forms, radio interviews like we hear on the radio and ordinary discourse, ordinary dramatized scenes. But for me, the eyewitness account, the eyewitness account is not a dramatized scene. It’s not novelistic, it’s not … People are asked usually 10, 20 years later, “What happened to you on the day that Chernobyl went off?” Or the day that the May ’68 Revolution happened, or what was happening to you in Germany in the spring of 1945. They collect these, I collect them, and they don’t read like ordinary fiction.

Nobody starts out, “Well, I had breakfast that morning and it was scrambled eggs, and I was having a conversation and the phone rang,” the way a dramatized scene would happen in a novel. No, you get to the point, and you judge it, and you explain the meaning of it to you and to history. These eyewitness accounts, I love them. And I wrote in Ministry, I would say I never counted. And not that I don’t want to know numbers like that, but there must be 20 or 30 of them in Ministry for the Future. I know there’s 106 chapters because there’s the number at the end. Twenty or 30 eyewitness accounts. And each one of those was just being taken up.

And as a novelist, this is the golden zone. I’m gone. The story’s talking or characters are talking. It’s the greatest feeling in the world. So the eyewitness accounts were the thing that was turning the key. When I was writing Ministry, I was thinking, “This might be the form,” a kitchen sink, a mixed picture, all kinds of genres. And so when you start a chapter in Ministry, you don’t know what kind of narrative it’s going to be. It takes a couple paragraphs to get oriented and you go, “Oh, this is going to be one of these.” There’s the polite host and the grumpy guest, they’re very recognizable. It goes on like that, the riddles don’t have answers except twice they do.

I think I solved the form problem. I could feel it while I was writing that novel. And the response since has been mind-boggling. But also the most beautiful part about it is not that, “Oh, I finally roll the dice, something comes out, roll the dice” … I’ve written a lot of novels; I’m trying my best to try something new. I always go on. But in this case, not only did the roll the dice come out right, I think, but people still respond to novels. I know this for sure. I can witness to this fact like an eyewitness. I spent three years listening to people talk about Ministry for the Future to me.

And they always want to tell me more, “Oh, you talked about regenerative agriculture. It’s a lot harder than you think. Let me take you out to this field where I’m working on it.” It goes on and on that. I’ve learned so much. I got an email from India saying, “I call my husband the ox also.” So the novel still has power, and I love that.

Katherine Snyder: And I want to tell you all about Ministry of the Future, too, and I’ll try to let you tell us. And you’ve done, you’ve captured some of the diversity of styles and forms and characters. I was interested that you emphasize the human characters because one of the things that’s so striking here is especially in those riddle chapters, it’s like, “I am like this. I’m like … I am a photon. I am computer code.”

And so you have these non-human narrators, and it makes me think about the rights of future humans as well as the rights of future non-humans. There’s something in your work that identifies not simply the human experience or humans as agents, but they’re within a real diversity. You said, well, the whole thing about I am a rock. It’s like, “OK, you know?” So that’s more of a comment than a question.

Kim Stanley Robinson: I would like to say something about that.

Katherine Snyder: Please.

Kim Stanley Robinson: This 18th-century it-narrative, where you are a coin and the coin tells its adventures going from person to person, is the 18th century, very rowdy, scabrous literature. And so naturally, the coin would get eaten and go through somebody’s digestive tract and get shitted out and how exciting. But the it-narrative died as a literary genre because the its don’t have agency. So they’re helpless, passive witnesses. And in fact, I think that I just reread Tom Jones. Tom Jones is like an it-narrative because Tom just bounces from pillar to post and he’s like a coin being passed around. He doesn’t have much agency either, but we’re interested in agency.

So then the other thing I want to say is Bruno Latour, the science studies was Latourized by Bruno Latour, God bless him. And he was actor-network theory. And I realized that science studies has gone way beyond actor-network theory, and they now think, “Ah, well, the reason that the bacteria isn’t as important as Pasteur is precisely agency.” In an actor-network like the Sierra Nevada being turned into national parks. The Sierra Nevada was the obvious actor there, and all the humans were just being told what to do or inspired what to do by the mountain range itself. A very important actor in that actor-network.

But agency matters so I had a lot of fun with the it-narrative sections, but you notice they’re short and they make their point and then get out of there because a carbon atom, it has an interesting story to tell, but not as interesting as the story of the people playing with the atoms.

Katherine Snyder: Oh, thank you. My next question has been raised and answered to some extent in your conversation with Daniel. But I want to talk about the pleasure, and I want you to talk about the pleasures of the speculative world-building in your fiction. And in particular, as I was re-reading Ministry, I kept wondering about how the imagined world, and especially the speculative technology and the speculative finance, how real these things were, like the things about the refreezing of glacial meltwater and solar airships or the carbon coin. I kept getting my friend who’s a sustainability economist to explain to me about quantitative easing and carbon coin and whether that was a thing.

I also was wondering about the opposite, whether there have been real-world technology or economic experiments or projects that have been inspired by or modeled on what you’ve imagined in your fiction. And so I guess my question, this is a two-parter, which has to do with how fictional is your science fiction, but also how do you understand what fiction, and particularly science fiction, speculative fiction, climate change fiction, how do you understand what fiction can do in and for our world?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, we’re all addicted to stories, and we all get a big supply of stories every day. And it can be anything from Tweet length to giant, mega novels that are 12 volumes long. Everybody has their favorite form. We like stories, and it’s very often argued by philosophers or people talking about epistemology that we only understand the world through stories because we’re stuck in time, and we have a narrative because of the chronological sequencing of information. We seldom get blasted by a ton of information in the same second. We usually have to sequence it through a story.

But in terms of what my novels has done, I’m mostly a reporter. I just look in the various science journalist sources, things like Nature Briefing or Science News or Society for Environmental Journalists, what’s happening at the cutting edge and occasionally finance papers, etc. There was a finance paper about a carbon coin, Delton Chan, I put his name in the book. He’s roving the world now talking about this. But there was a network for greening the financial system, which is a think tank made of central banks that was already on all this stuff and I didn’t know it when I wrote the book.

So you can’t possibly be on the cutting edge. You can claim to be a science fiction writer or the people I run into now at conferences who claim to be futurists or futurologists. And I just got to say, they’ve got to be kidding. They’ve got to be kidding because everybody is a futurologist, everybody is a science fiction writer and that somebody could become an expert at it and do more than the ordinary person that’s mostly a business scam. It’s a consulting scam. It isn’t a real thing.

They are science fiction writers pretending to be nonfiction profits. And if they charge you $10,000 for their story instead of $10 for their story, then they’re a futurist instead of a science fiction writer. So I just follow the news and try to keep up, and then I push it. This is called “straight-line extrapolation.” If this goes on more of the same, and then you realize there’s never going to be more of the same for very long because of the logistical curves of running out of resources that you need to make it go on. I mean, Moore’s law is not a law. It’s just an observation of 20 years and the logistical curves are going to hit everything.

I will say that I made some mistakes. I wish the word blockchain did not appear in Ministry for the Future. It should have been code, it should have been cryptography, it should have been digital money, but it should not have been blockchain, which is perhaps clumsy and a contaminated version of coding that has to do mostly … Well, blockchain has mostly to do with Bitcoin. Bitcoin is a scam. It’s all bad. I want to talk about fiat money doing real things in the real world, fiat money. So I should have talked about code. And then there are dirigible companies and there are sailing ship companies that say to their customers, “Oh, you ought to read the Ministry for the Future.” It’s going to be like that.

That’s all speculative, and it’s trying to keep the pleasures of travel in a carbon-neutral world. How do we get around? Well, we got around the world without carbon very easily up until about 1900, and we might go back to that again, I hope so. So I’m just playing a game of trying to make a utopian future feel plausible because strands of it are coming right back into our present. And in terms of Raymond Williams, the residual, and the emergent, I’m trying to make the emergent more visible by pushing it a little. And in near-future science fiction that’s almost the name of the game.

Katherine Snyder: For my last question. I’ve got more, but I’m running out of time. Oh, God, I’m not used to it. So I wonder if you can tell us about a few of the other writers of climate fiction or climate-based artists that you particularly admire. And without naming names, I wonder if you can tell us whether there are any contemporary approaches to the climate crisis in art that you think are more harmful than beneficial.

And I’m thinking here now about the popularity of the post-apocalyptic in movies and fiction of the past few decades. And I’ll confess, I love that stuff, but I realize that an aesthetic taste for the apocalyptic sublime has its political problems. Yeah, so I’m asking what do you like and what don’t you like? Who’s inspired you and what alarms you?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Well, I don’t like any dystopias anymore, and I now think of it as a comfort food, a self-indulgence. You read in a bourgeois comfort of these horrible futures, and you come out of that, and you go, “Well, I mean, I’m in a precariat, but at least I’m not as bad off of those people that are eating each other’s arms and eating their cat and all that.” And the dystopia A, it’s a little too easy to imagine because on the brink of bad social collapses. But B, it will be worse than these stories tell in that you, yourself will be dead. And if you’re not, life will be boring. Boring and tedious. And that’s what apocalyptic and dystopian fiction…

It’s all so exciting. So you do have great symbolic statements, The Hunger Games, that’s a dystopian future. The rich are making everybody scared, or they’re making them fight each other for the entertainment of the rich. To be young is to be screwed. The Hunger Games is a great statement of how things feel now, or when those books were written. It’s a surrealism, it’s a prose poem. As a logical future, it doesn’t add up. I mean, who’s making the bows and arrows, etc. But that’s not the point, right? It’s not just fiction. It’s surrealism. It’s made to say, “I feel like this and it’s not good, and I wish I could kill you.”

And so it’s a popular narrative, but the dystopias that, oh and embattled little group of people that are good with guns can survive and be happy despite the zombies that are trying to eat them. And you get to kill zombies with impunity because they’re not human anymore, blah, blah. These are just fantasies of fearful… That you come back to your world thinking, “Well, at least I’m not that bad.” So you need utopia, you need the positive futures. And there it’s pretty thin on the ground. It’s one of the reasons Ministry is successful is when you say, “OK, I’ve read that book. I’m going to read another one like it.” And where do you go?

Well, Cory Doctorow is very good. He’s a wonderful teacher, a tech expert, and novelist. Jonathan Leatham, who lived in the Bay Area for his formative years, and is a friend of mine, his book, The Arrest is finally… A child of hippies who has a lot of resentment, a big chip on his shoulder about hippies bringing up kids, which his latest novel is all about. He’s finally reconciled like, “OK, maybe the hippies are terrible parents, but their life way is better than every other life way. So dammit, maybe they were right.” That’s the arrest. That’s how I read Jonathan.

There are some dystopian narratives or coping narratives. James Bradley, Lydia Millet. The Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet. That’s pretty good because people are coping with disasters rather than going into the fantasia of power and survival.

Daniel Aldana Cohen: Let me bring up one other sci-fi writer and often thought of as dystopian — Octavia Butler. And your work is very different, but she has, there’s a key phrase, a mantra from the Parable series that I found in Ministry, and that’s not exactly the exact words, but she says, over and over, God has changed. And that’s the basis of this earth seed idea. And I thought of that when I was reading Ministry, or rereading it for this conversation. There’s a phrase when you describe things turning for the good and somebody says, “Change itself is changing.” And that really seemed striking. Not just that things change, of course things change, but change itself is striking.

And then that you picked up that idea, and I think you really drove it home with another phrase in the book, there’s no such thing as fate. You say twice on the last page of the book, which in my copy is only half a page. So it’s a very strong concentration of there is no such thing as fate. Where do you go? Whether it’s spiritually or physically, maybe it’s the Sierras, to really feel that. I mean, to be able to believe and to put this out, this idea I think animates a huge amount of your fiction. How do you retain that optimism, that sense that there is no fate even after every season of disappointment and every difficult and turbulent year.

Katherine Snyder: And actually, before you answer, I want to tag on with my last question, which is very similar and I want to make sure we have time for the Q&A. And it’s ironic that you say, I want to write a story about death, death, death, because so many people comment, as you just did, on your optimism, and critics have called you sunny in a good way, I know. Not sonny with an o, but sunny with a u. You have a sunny personality.

Kim Stanley Robinson: Yeah, but optimism is code for somewhat stupid.

Katherine Snyder: Right. And I know you don’t like that. And so another term that has been used to describe you is anti-anti-utopian, and not coincidentally, this is a term coined in Archaeologies of the Future by Fredric Jameson, who was your long ago dissertation adviser, and also the person to whom Ministry is dedicated. And so I think it’s a similar question to ask whether anti-anti-utopianism captures something of your thinking and what this perspective makes possible. So I think it’s a similar question about the possibilities for change.

Kim Stanley Robinson: Yeah, I see the connection between them, and I want to … How much I love my teacher, Fred Jameson. He turns 90 in April. We’ll have a party. He’s still lecturing, teaching at Duke in these rather extraordinary lectures that they record. And I listen to them as podcasts. I listened to one on Hagle this morning driving down here. It was awesome, Fred on the freeway.

So yeah, there’s no such thing as fate, but there is path dependency. So our built infrastructure sets up a kind of a fate that will last for a while unless you change it because built infrastructure does shape social realities in a way that design and architecture and all these other fields know very well.

And having lived in a hippie suburbia and a regular suburbia, built infrastructure really does change social realities. And we are in a certain built infrastructure that’s fossil fuel-powered right now. So that’s not a fate, but it is a path dependency. And then, the great acceleration that this is social science, all the social sciences since World War II, everything we measure about humanity has been accelerating. And sometimes in a famous hockey stick style, can’t go on forever, but boy, it sure has shot up for a while.

And so there is path dependency in some levels, an acceleration in everything in other levels, including population, human population. So there’s a tension between those two. That is one of the reasons things feel so crazy. So then how do you keep a sense of hope or optimism in that? Well, this is Gramsci, pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will. That optimism is, sometimes it’s biochemical. For myself, I can say yes, I owe this to my mom, a biological glass is half full. But she had to hold that position as a personal and political fact as well.

I’m staying hopeful so that I can … when I punch you in the face, you’ll go down because I hope for that. So it’s a fighting position, angry optimism, and you need it. So somebody, just a couple of days ago, talked about Ministry for the Future being a pedagogy of hope. And I was thinking, “Oh, that’s nice.” Not just why should you hope — because you need to, to stay alive and to hold together and all these other reasons you need hope, but also, it’s strategically useful.

And then how to hope in the situation that we’re in, which is filled with dread and filled with people fighting with wicked strength to wreck the earth and human chances in it so that the political battle is not going to be everybody coming together and going, “Oh my gosh, we’ve got a problem, let’s solve it.”

It’s more like some people, “Oh, my gosh, we’ve got a problem that we have to solve.” Other people going, “No, we don’t have a problem.” They’ll say that right down over the cliff. They’ll be falling to their death going, “No problem here because I’m going to heaven and you’re not or whatever.” Nobody will ever admit they’re wrong. They will die. And then the next generation will have a new structure of feeling. In the meantime, how to keep your hope going, how to put it to use. This is certainly one of the things that, first of all, I think all novels have a little of this, and then Ministry is just more explicit.

Katherine Snyder: Thank you, Stan. I just want to say thank you on behalf of everyone here. You are an inspiration, and you give us hope. So thank you. And so I think we have time now for Q&A.

Audience 1: Hi, Stan. Thank you. You write in Ministry for the Future that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. Our gracious hosts talked about the inundation of post-apocalyptic novels and stories maybe being the case for that. My question for you is, which is easier for you to imagine the end of? And if it’s the end of capitalism, what real-life movements or relationships or stories or political figures or cultural or otherwise are helping you in your visioning?

Katherine Snyder: Why don’t we have …

Daniel Aldana Cohen: Take several questions and then yeah. OK.

Kim Stanley Robinson: I’ll remember. I’m going to do speed answers to try to maximize.

Audience 2: [Choppy audio] Stan, you had to mention the Sierra Nevada, which comes through in some of your characters. And you’ve written a great book. I put off reading it too long, but I enjoyed it when I did. And can you comment on how that’s made, shaped some of your main characters and your experience [inaudible]?

Audience 3: Hey, I was really interested in what you were saying about the impossibility of being totally cutting-edge about everything that needs to go into the construction of a future. And I was wondering if you feel like that’s a foreign problem for you and what you feel like you’re doing when you’re writing a novel to try to respond to or confront that problem?

Kim Stanley Robinson: I’m going to go in order, and I’ll remember all of them. Post-capitalism is a situation devoutly to be wished. That we need it bad because capitalism is a name for inequality and destruction of people and the earth. It was an accident and it’s a power relation and it’s going to have to be wedged out of power. But we’re also in a climate emergency, so I’m looking to see if the accounting system used, rates good activities as more valuable than bad activities. So you got to get rid of gross domestic product, you got to get rid of profit as a measurement of what actions are. Then it begins to look like an accounting change.

And I want to describe, which is my utopian future or my anti-utopian, is you simply deny that neoliberal capitalism was right. You go back to Keynesianism where government controls the economy and tells businesses what to do. You’re at a mixed economy at that point. Then you go to what you might call from Northern Europe, the social democracies where there’s a better safety net and there’s adequacy for all and also a tax rate. So social democracy, if that then leads to democratic socialism or let’s take the 20th century names off of it, a better system. That’s why I often call it post-capitalism, then that would be good. The faster, the better. The climate crisis might force it.

I want to say, this is a strange analogy, but the clean energy transition in Europe was massively forced and accelerated by Russia’s brutal war on the Ukraine. It illustrated something and it made material results. If climate change forces us into post-capitalism faster just as a survival mechanism, that’ll be one of the good things that can come out of a bad situation. And as for inspiration, I just want to give great thanks and honor to Bernie Sanders because, in a two-party system, the party on the left has to be drug further to the left.

And you can’t detach, you can’t make a third party because this is all about blocks. You’ve got to take the party that is going to do the work and you got to drag it as far in the direction you think it ought to go as possible by advocacy within it. That’s what Bernie did. He was also a united front, a good soldier when he saw that he needed to support someone else, he supported someone else, a model citizen, you got to say. And may there be more of them, younger. He’s only a tad older than I am, but it’s time for the younger generation. There’s more energy, more quick-wittedness.

And, Roger, I’ve loved the Sierras so much all my life. I just hit the 50th anniversary this last summer of my first trip up there. I took the same entry hike with my wife, and I was going, “God, this is really small scale compared to what I remember.” But of course, I was frying on LSD at the time, and I was 20 years old and I’d never seen it before. So it looked awesome that first time. And now it looks like your ordinary hike up from Emerald Bay. I mean, it’s rather small scale even. It made me laugh. I laughed my head off. I’ve loved it all my life.

And very often my characters, for some reason, they say to each other, “Well, we got a plot here, but let’s go for a Sierra trip.” And I described that as happening like in my DC novel. Every excuse I could get to write about the Sierras I’ve taken, it’s not a good situation for writing taught novels that stick to their plots. So when I got to write nonfiction about the Sierras, it was a huge joy and a release, and I recommended it to everybody as the backbone of California and an incredible spiritual anchor, grounding place, and so beautiful as the days up there are just beautiful.

And then in terms of keeping up with the world for writing science fiction, harder than hell. And one solution though is don’t take on the world novel. Don’t do the totality. So no more ministries for the future for me in terms of form. These last three years in order to talk, sometimes I’ll get an invitation, “Oh, will you please come to the World Trade Organization and tell us how to improve the trade rules of the world?” I said, “Sure, I’ll do that.” But then I’m screwed because what do I say, as an English major, not really hip to the trade rules of GATT, etc. I have to swat it up like I’m taking a final at UC Berkeley.

And you know what finals papers look like? They’re very sketchy, they’re very partial. They don’t know the whole story. I’ve been accidentally cast into a role that I’m not well suited for. I can write a novel, but I can’t be a world expert. And so I’m going to focus in and that will help me.

Audience 4: Thank you. Like probably everybody here, I’m a big fan of your book. And this morning at UC Berkeley, even though the lecture was sold out, I still held up the book and said to students, “Well, you should know about this.” And I characterized it, I think the way probably most people do, is they said, “Well, it starts out really horrible, but eventually the world wakes up and in desperation gets their act together, has an optimistic ending.”

And I guess I want to press you on that a little bit because if you look at, when I think back to the late ’80s, early ’90s, when the world was still under 350 parts per million, it would’ve been way easier to solve the problem.

And of course, you had this massive opposition from the fossil fuel industry and climate denial and taking over the republic body, etc. But the vast bulk of people I think were, “Well, yeah, maybe really the science is right. Maybe really eventually it could be a big problem, but it’s not a problem now, though. We can wait. You don’t have to do anything now. Eventually, we can do something, we wait.” And in a sense, even Ministry of the Future still plays into that narrative. They’re saying, “Well, it hasn’t gotten so bad yet, but when it does, then people will do the right thing.”

So a couple of things I want to ask you about that. Is it possible that it even still encourages, even though it’s optimistic and people love that we’re not totally screwed, I’m not sure that that’s right. I think we all wonder about that. But you’re saying, “Well, it gives people comfort.” I think Ministry of the Future eventually will be OK. So number one does that still feed the complacency of we don’t need to act now. And number two, is it possible that even as it gets a zillion times worse, people still won’t get their act together?

Audience 5: Thanks. Actually, this dovetails on that, but I was wondering, it seems to me in the book the thing that really gets things moving, because everything gets worse and worse and worse, and the thing that finally, some people get so frustrated that they actually act out in violent activism like crash day and things like that. And so you said you’re less angry now than you were when you wrote it. Is there a less angry version of crash day that actually gets things moving?

Audience 6: My question is like the third alternate reading of the book of these three questions, which for me, in the younger generation, it was very inspirational to act. I think we talked about hope and optimism and agency as literary mechanisms for that. But I’m also curious if the intention was to inspire action or if that was just a happy precipitate, is it something you’re going to go back to in the future writing or is it just more novels about death and the such?

Kim Stanley Robinson: Yeah. Thank you for those. And I’ll take them in order. Michael Lewis has a great book about the federal government, The Fifth Risk. And since my wife was a federal scientist her whole career, I love this book by Lewis because he’s basically showing us how good federal scientists and technocrats are. And he goes to Ohio where a tornado has just ripped through a town and torn it to shreds. And he goes to the next town, like 10 miles to the south, and he says, “Are you worried now?” And they, “Oh no, we’re not worried.” They’re in the tornado track and we’re not. And you’re thinking, “The tornado track is like from Ontario to Texas, dude. What are you talking about?”

But that’s how humans are. If it doesn’t happen to you, it won’t happen to you. And we have powerful psychological mechanisms to avoid thinking about our own death. And also climate change is always going to affect people who are poorer and without electricity, and we’re somewhat sheltered from it by our tech. So it is a huge problem. And if something bad happened, like the event in India, and in my novel the world doesn’t change. Twenty million people die and there’s a lot of talk and guilt and India takes action. No one else does. It stumbles on from there. It takes another, I think 30 years to get to something.

But one of my teachers at COP 26, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, a Jordanian diplomat, he said to me, “Stan, you don’t have to be in a plane crash to know that a plane crash would be bad for you.” And I was thinking, if you tell the story, then people will at least have the idea. And I want to come back to this. The pandemic was the slap in the face that made Ministry seem more realistic. Like, “Oh, this could happen. And I myself, am sheltering in place all day every day. I’m not immune from biosphere disaster.” So in that sense, the book was taken more seriously because of the pandemic.

I want to remind people because it blew my mind that killed one of every 1,000 persons on Earth. It’s more than I thought. And if you had said you’ve got a one in 1,000 chance of dying, you would not be happy. That’s a pretty big percentage of humanity. It was 8 million out of 8 billion. And then so violence, yes, the less violent, first of all, I read Andreas Malm. He hadn’t published How to Blow Up a Pipeline. My book should have made a much better distinction between sabotage and murder as forms of active resistance to climate change, denial and the fossil fuel industry, etc. I now am thinking the last thing we want is more violence or terrorism. It always rebounds against you.

Probably one of the least realistic parts of the Ministry for the Future is that the Children of Kali are coherent, targeted, intelligent and on task — unlikely. It could happen, but it’s one of the more fantastical elements in that book. And so now, yes, I definitely have less violent notions in mind.

First of all, if you need to be active and resist, which I could well see people trending that way, it would be sabotage, not murder. It makes a huge difference. Someone told me something that affected me very profoundly. There should be a chapter in that book where some, a parent and child are going down on crash day in a plane. That should be one of those short chapters and then the stakes would be made clearer, the killing of the innocents.

We know how bad that is now, and we always knew that. And I just want to say my book is as messy as history itself and it isn’t my fault, but in fact, I could have clarified some issues there. And then inspiring action, I’m seeing it. Many people have come up to me and said, “Chapter 85, that’s my favorite chapter,” all it is a list of environmental organizations that already exist. I took it off of Google Maps and it takes about 10 to 15 minutes to read it in the audiobook. So I’m thinking, well, “That’s a funny chapter to like.”

But what it means, there’s things you can do now. And I put it in there to suggest the local without getting caught up in the local for the sake of the novel. And so there are things we can do. I went back to Village Homes Davis after COP 26, and I said, “Well, that was absurd.” Because the world, diplomacy gets together, international scene, it’s all very important. But for me, especially my role in it like court jester or something, it was like a piece of theater. What can I actually do? So I rejoined Village Homes’ board of directors in Davis, California. I go to a meeting every week, a big meeting every month, they’re Zoom or they’re in person.

We’re running a 200-household village that has a commons that is a kind of a hippie suburbia. We own the land together, we garden it. Village Homes is great. It’s just minuscule and a privileged space. It’s a well done suburbia. It’s nothing special. But we do govern ourselves and I’ve got my hands in there. I’m one of five votes on real issues, and I’m trying to get a preschool back into the village because some neoliberals came in and between them and the pandemic, our preschool died after 37 years, but it was killed. And a lot of us were furious.