Soon, California educators must teach ethnic studies. UC Berkeley is helping them prepare.

As one of the first universities in the country to create an ethnic studies department, Berkeley is helping high schools chart their own path.

UC Berkeley/Ivan Natividad

March 27, 2024

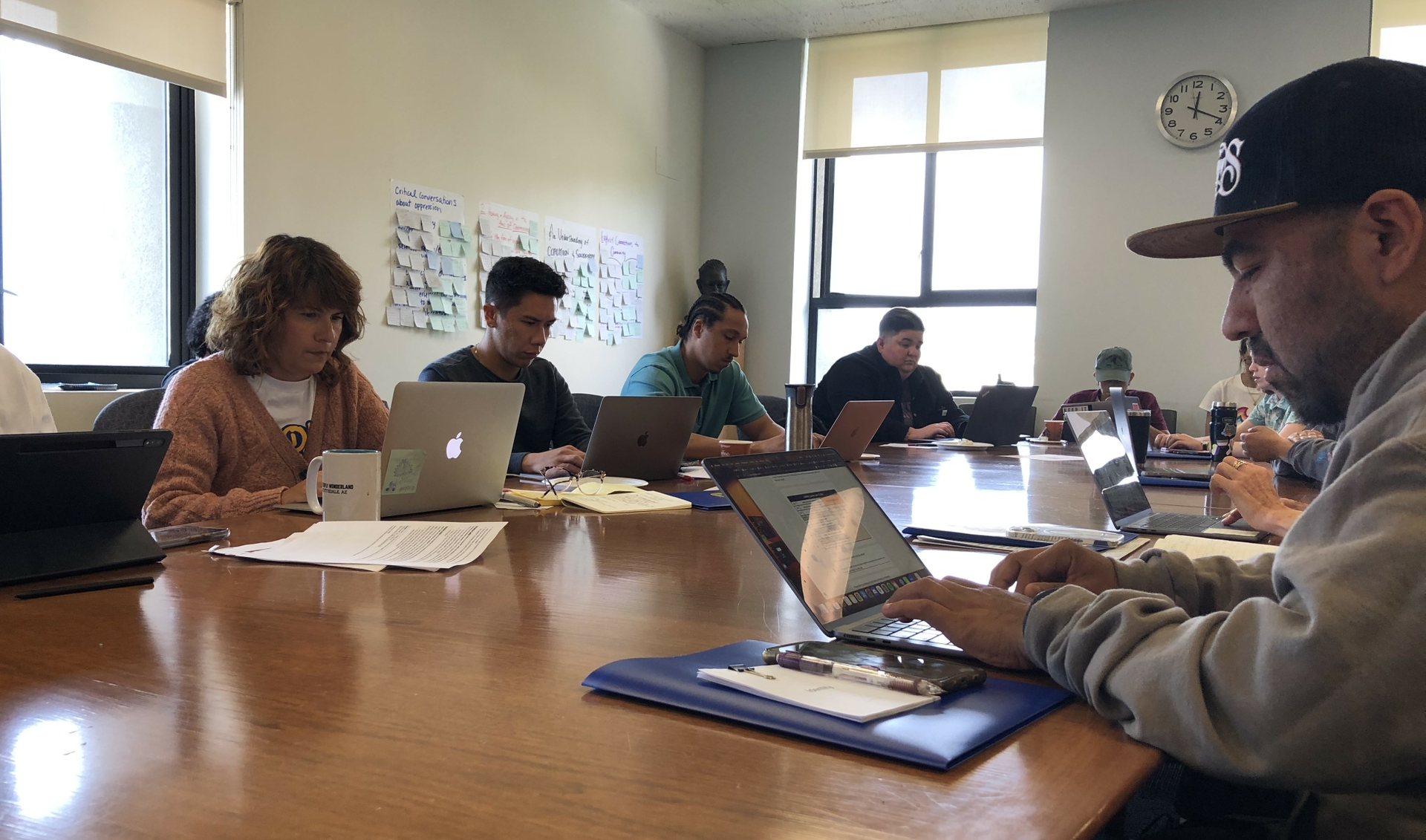

Starting in the 2025-26 academic year, by law, California’s public high schools must begin teaching ethnic studies, and students in the Class of 2030 can’t graduate without passing a class on the subject. But while the state, which enacted the law in 2021, has adopted an Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum focused on the contributions of Asian, Black, Latino and Native Americans in U.S. history, it’s not required for educators to obtain a specific credential to teach the discipline.

UC Berkeley/Ivan Natividad

Public school districts in areas like Oakland and Fresno have taught ethnic studies for years, but many others have not. So how will teachers in these districts introduce their students to the interdisciplinary study of race and ethnicity if they’ve never taught it before?

Insert UC Berkeley, where, as one of the first universities in the country to create an ethnic studies department, faculty and staff across campus in recent years have stepped in to help California teachers by offering resources, workshops, courses and conferences: a community of support.

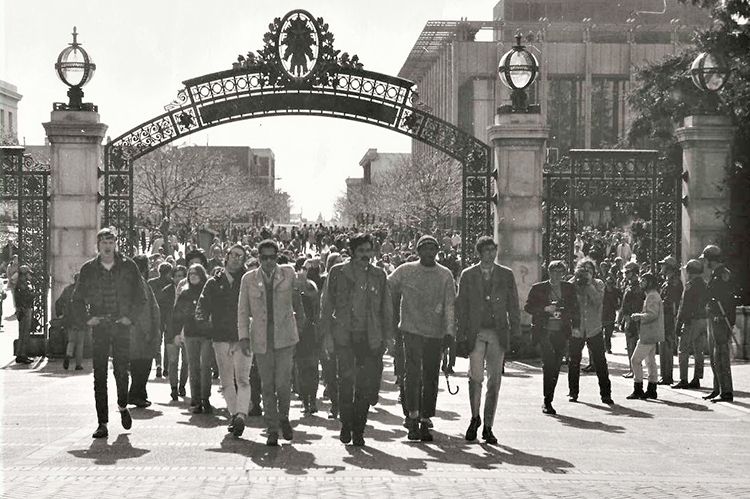

These offerings help fulfill Berkeley’s public mission to serve students from all backgrounds and are part of the legacy of the late 1960s, when the student-led Third World Liberation Front — which demanded and won more spaces and resources for students of color, first-generation students, working class students and other underrepresented student populations — led to the creation of the Department of Ethnic Studies.

Courtesy of Oliver Jones

Today, the department and Berkeley’s ethnic studies scholars are internationally known.

“Our campus has unique and robust ethnic studies scholarship and research where educators from all backgrounds can learn from our history, to understand what our public schools and prospective students need in the future,” said Dania Matos, Berkeley’s vice chancellor for equity and inclusion.

UC Berkeley/Ivan Natividad

The study of history through the lens of ethnic studies is a new frontier for many educators, said Bridgit Lee, a high school teacher in the city of Soledad, who added that she has benefited greatly from what Berkeley offers.

“It has really opened me up personally to seeing the world through a different lens from the conventional white-centric American history I grew up with,” she said. “These histories that focus on marginalized groups need to be understood because history is often seen through a singular narrative.”

Heather Garcia, a Santa Rosa teacher who has attended several ethnic studies workshops and conferences on the Berkeley campus, said she’s gained “the confidence to forge ahead to teach this new curriculum in our classrooms. I truly feel like I have a well-informed foundation and community of teachers and scholars that I can turn to if and when challenges come my way.”

Offering new, invaluable resources

Over the years, Berkeley’s ethnic studies community has collaborated with scholars from many disciplines on campus to help empower and enrich educators.

One of its innovations is the High School Ethnic Studies Initiative (HSESI), which since 2022 has given Bay Area teachers and school districts free, year-round access to comprehensive digital resource hubs, workshops and conferences at Berkeley to help inform and shape ethnic studies curriculum in their classrooms. The initiative is led by Berkeley’s History-Social Science Project, American Cultures Center program and Department of Ethnic Studies.

Photo courtesy of Department of Ethnic Studies

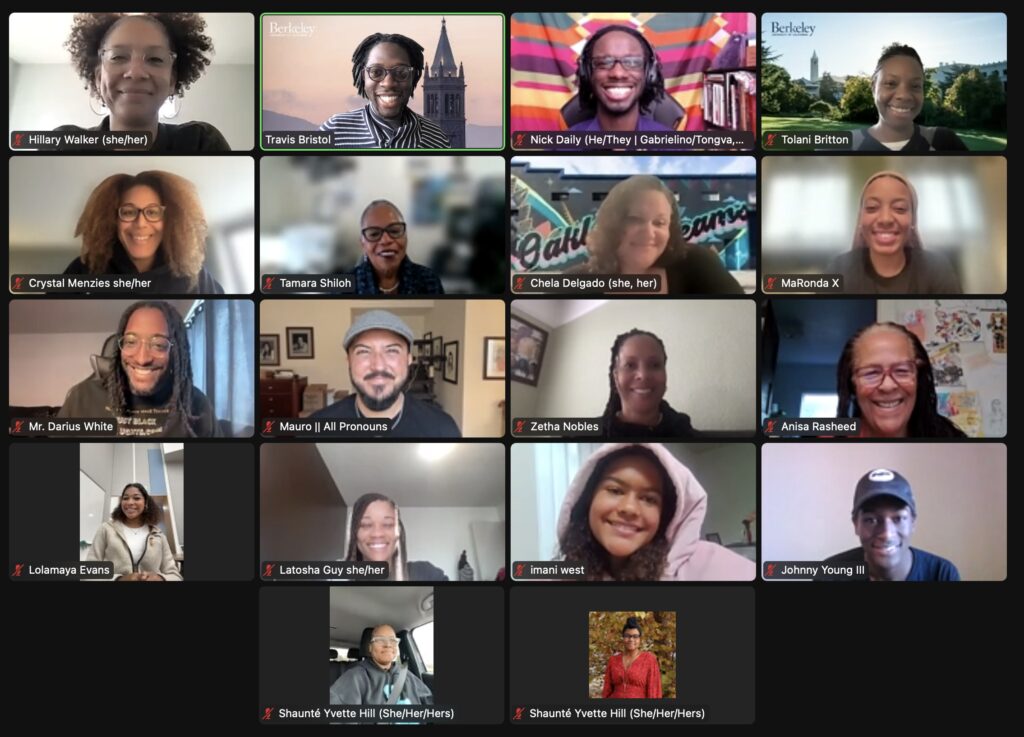

Events currently offered on the HSESI website include a series of panel discussions led on Zoom by Berkeley scholars and others that teachers can register to attend. Recordings of past discussions — like the Jan. 30 “Hope, Healing and the Warrior Women” discussion, about the legacies of Native women activists — can be found on the site, too, along with distilled key takeaways and curated resources.

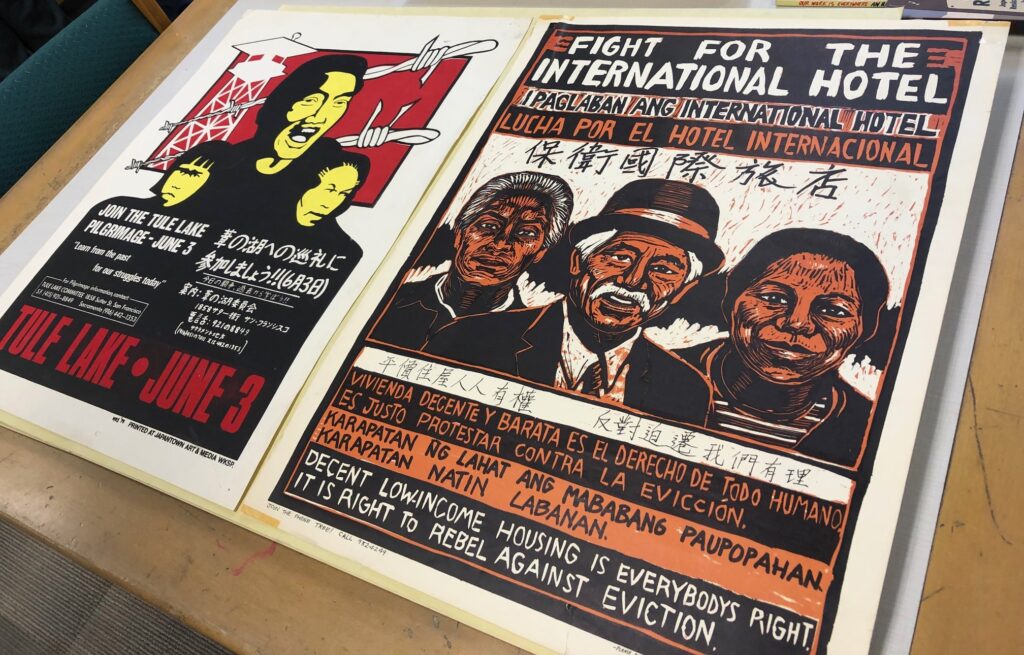

Teachers also can access the campus’s historical archives, book lists, and video clips and films through the initiative’s media library and resource hub.

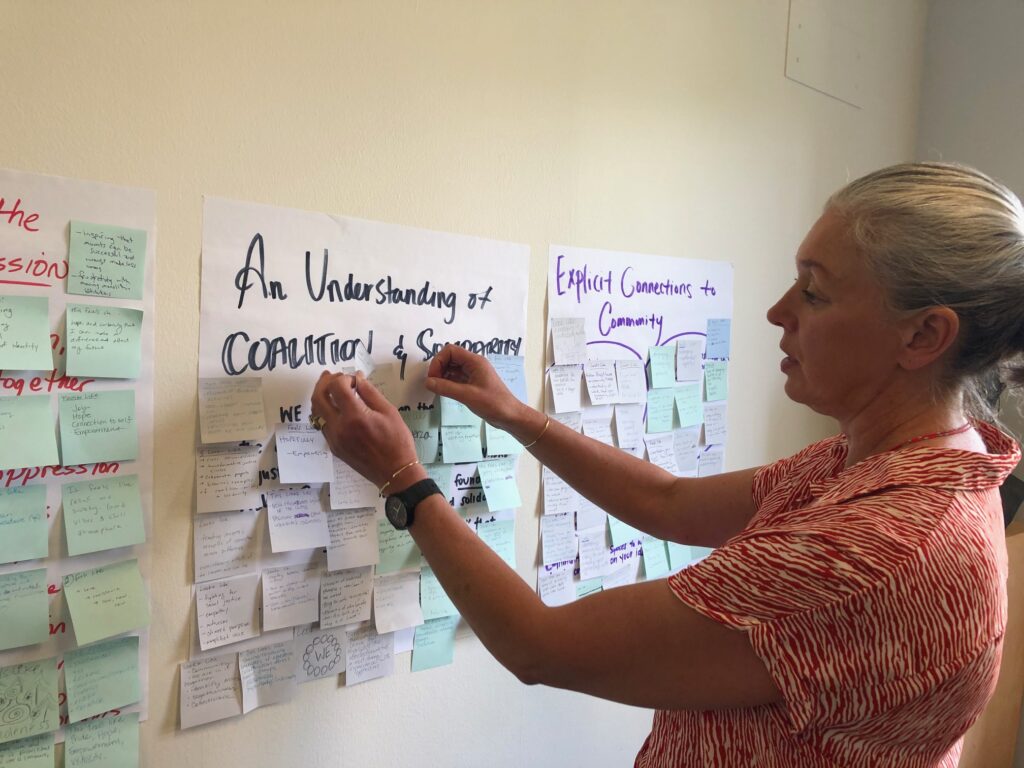

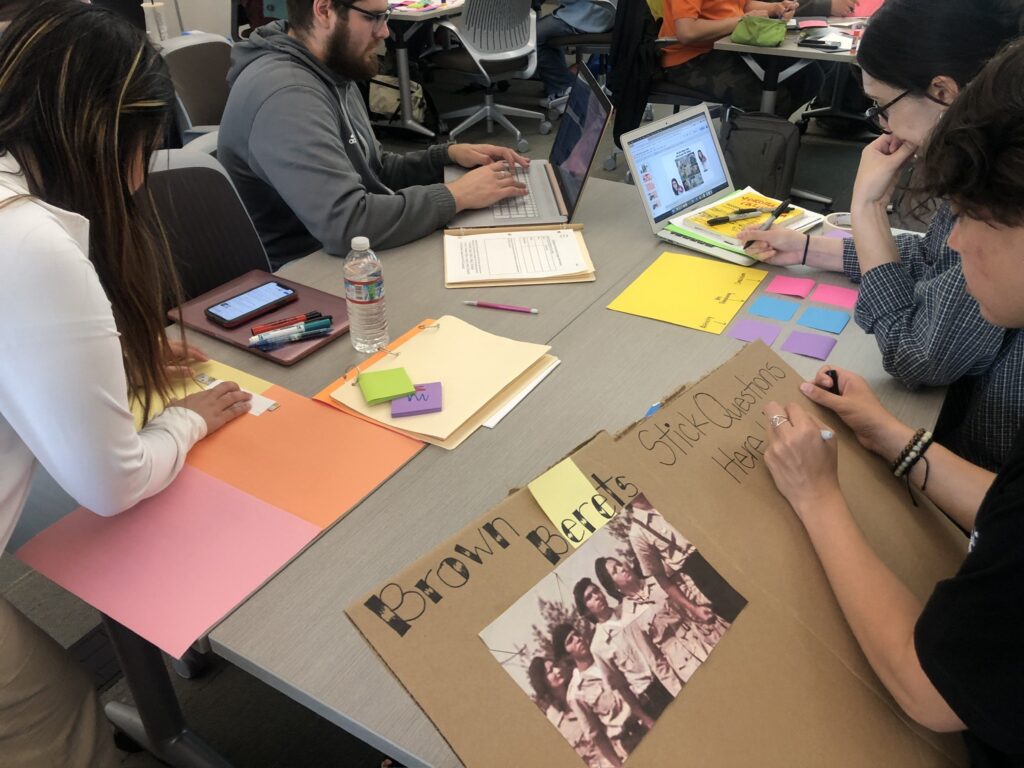

Last summer, nearly 30 high school teachers from across the state convened for a HSESI conference at Berkeley, attending a week’s worth of sessions on how to design a thoughtful and effective ethnic studies curriculum.

UC Berkeley/Ivan Natividad

The high school teachers delved into Berkeley’s African American and ethnic studies library collections to examine historical archives dating back to the student movements of the ’60s. And ethnic studies faculty members gave them presentations on how to use digital media, podcasts and augmented reality to create engaging classroom sessions about the people, places and ideas often left out of history books.

Christopher Williams said he left the week-long conference with substantial examples of assignments he can in his classrooms and share with his colleagues. A lifelong teacher and educator, Williams said he has already taught ethnic studies in his classes for several years in middle and high school settings.

Courtesy of Christopher Williams

Coming to Berkeley allowed him to delve into a more nuanced curriculum.

“To be able to pull from documentary films and archived newspaper clippings about the struggles and genocide of Native people in America is invaluable for me as an educator,” he said. “This will bolster my capacity to tackle new and uncharted territory.”

Jason Muñiz, site director of Berkeley’s History-Social Science Project, said teachers at the conference were also given a space to have conversations about their personal struggles as educators, and to build solidarity with the group and with Berkeley faculty and staff members.

The HSESI, which is ongoing, aims to eventually support the creation of a certified ethnic studies credential that teachers can obtain. Also proposed is a two-week fellowship where teachers can read and research ethnic studies texts, participate in seminars and workshops, and develop their own ethnic studies curriculum that would be shared in an online repository — for teachers and by teachers.

‘A labor of love’

At the Berkeley School of Education, faculty and staff in the Berkeley Teacher Education Program (BTEP) offer courses for graduate students, who are current and future K-12 teachers, that include an introduction to ethnic studies classes, as well as subjects that cover specific ethnic studies teaching pedagogy.

In addition, the Berkeley School of Education offers professional development workshops to ethnic studies educators through the Bay Area Writing Project (BAWP). Directed by Hillary Walker, the project helps teachers in many disciplines who want to write their own ethnic studies materials. Last summer, BAWP partnered with UC Davis to run a two-week Ethnic Studies Critical Literacies Institute.

UC Berkeley School of Education

Also creating teaching materials — to help tell the story of Black history in California — are two faculty members who want to share them with teachers in K-12 schools. Tolani Britton and Travis Bristol, a wife-and-husband duo of associate professors, are putting together a new California-centric Black studies curriculum based on research from the state’s Task Force to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans, on which they both have served.

Topics they will cover range from the impact of the Harlem Renaissance on California’s Black culture and community to contemporary issues, like the taking of land from Black people in California through government policies of eminent domain.

Britton, a former math teacher from New York, said the long-term benefits of teaching subjects like ethnic studies and Black studies to students already have been proven, and that the purpose of the curriculum she and Bristol are creating will be to make it free and available “to anyone who wants to use it.”

“This is a part of history, and it deserves to exist in our classrooms,” said Britton. “And the beautiful thing about this work is that we started it by reaching out and collaborating with teachers, nonprofit leaders and students from our communities to understand what would work for them as educators. … It really has been a labor of love.”

Courtesy of Tolani Britton

Keith Feldman, a Berkeley professor of ethnic studies and chair of the department, said Berkeley has “passionate people who are uniquely dedicated to the mission of empowering and enriching educators from all backgrounds” about teaching ethnic studies.

Its “rich history of activism and research in ethnic studies,” he added, “can inform teachers in developing pedagogical curriculum that is specific to their students and communities.”

Campus experts lend their teaching chops

The scholars contributing to Berkeley’s efforts to prepare California’s educators to teach ethnic studies include Muñiz, who has traveled to K-12 public schools across the state to help teachers with educational practices and to provide professional development to refine their history curriculums for diverse classrooms.

Courtesy of Jason Muñiz

He also works with campus colleagues through HSESI to make ethnic studies resources accessible to high school teachers. On the HSESI digital platform, teachers can peruse curated teaching tools on topics like anti-racism, redlining and oral histories covering the Third World Liberation Front Movement.

A former teacher, Muñiz taught in public schools for over 10 years, including in East Oakland, where he piloted ethnic studies curriculum in history classes.

In collaboration with Berkeley’s American Cultures Center and the ethnic studies department, Muñiz has also hosted conferences and monthly panel discussions that explore topics like “How do we teach Pacific Island matters in high school curricula?” or “Teaching histories of anti-imperialist solidarity.”

“These are also spaces where teachers can create connections with scholars and relate to the history and curriculum in their own personal ways,” Muñiz said. “The discussions also give them a lens to conceptualize how ethnic studies informs contemporary issues that our communities and students are currently experiencing.”

Muñiz previously taught in Florida, where DEI programs have been defunded and where African American studies courses have been blocked from being taught in classrooms. California high school educators may also face that same political climate in their own communities, said Berkeley Ethnic Studies Lecturer and American Cultures Center Program Director Victoria Robinson.

UC Berkeley/Ivan Natividad

Robinson said high schools need sufficient time to specify their teaching of ethnic studies to reflect the demographics of their students. But due to extreme right-wing critiques against the importance of teaching ethnic studies, she added, teachers urgently need to try to “get it right from the start.”

“We want to avoid any political backlash that would create a false narrative that these curricula are not valid,” said Robinson, who will receive Berkeley’s Distinguished Teaching Award this year. “So, what we offer teachers is a cohort-based, supportive model that provides districts with a process to meet these new state requirements, but to also create the foundation for their own ethnic studies programs, moving forward.”

Tempering idealism with reality

For Berkeley School of Education lecturer Kyle Beckham, teaching ethnic studies, while rewarding, also inherently comes with conflict “in the classrooms with students and parents, in the schools you teach in, and in the district and community you live in.”

Despite studies that show the positive impact on students of ethnic studies, including increased overall engagement in school, probability of graduating and increased likelihood of attending college, critics call it political indoctrination, while others warn against course content and teaching approaches that are divisive, biased and designed to dictate thought and action.

UC Berkeley School of Education

Beckham teaches an introductory course for student teachers on ethnic studies pedagogy as part of BTEP. The program focuses on ways to implement ethnic studies into different academic subjects. But more importantly, Beckham said, it aims to prepare Berkeley students to navigate complex conversations and situations as teachers inside and outside the classroom.

On March 26, Beckham led a HSESI event and discussion, “How do we create healing spaces in response to controversial topics?”

Beckham, who helped create San Francisco Unified School District’s ethnic studies program, said that it’s sometimes “a shock for teachers to realize how much work this is. And some people will not like what you are doing.

“We will often role-play scenarios of dealing with upset parents, or community leaders that do not want students exposed to ethnic studies. So at times, it is a matter of tempering the idealism of our teachers and squaring their ideal vision with the reality of what it takes to build something.”

Ethnic studies through a personal lens

Courtesy of Fatimah Nadiyyah Salahuddin

Berkeley lecturer and BTEP secondary humanities faculty adviser Fatimah Nadiyyah Salahuddin has been an educator and a public school teacher for over 10 years. She teaches the program’s summer introduction to ethnic studies course, which has become a required class for all students in the Berkeley School of Education.

Courtesy of Fatimah Nadiyyah Salahuddin

In her course, students are given the opportunity to understand ethnic studies through the lens of their own cultures and experiences. Salahuddin said giving students the space to do that empowers them to conceptualize innovative teaching methods.

“They really do surprise me sometimes,” said Salahuddin. “Our teachers come from all types of backgrounds and lived experiences, so they are crafting assignments and curriculum pertinent to themselves, their students and the community they come from.”

Many of those students, like Leslie Cortes Sanchez, also are current Bay Area K-12 teachers. A Berkeley graduate student, Sanchez teaches a Spanish bilingual kindergarten class in East Oakland.

Salahuddin’s course, she said, has given her culturally relevant practices to use as a teacher. “Ethnic studies centers people,” Sanchez said. “So I try to center my students and make it so the activities I create are meaningful, where they can walk away with something that they actually learned.”

Courtesy of Leslie Cortes Sanchez

Recently, Sanchez used music from the Disney movie “Encanto” as a way for her students to learn and share their families’ cultural backgrounds through objects they brought to class.

“In the movie, each member of the family has an artifact that represents themselves,” she said, “so it was really fun for the kids to see themselves in that movie, but also to find a way to relate to their own family through an artifact.

“Our program at Berkeley has given me a new lens on creating lessons in ways that are equitable and meaningful to my students and myself. The program consists of a very supportive community full of students and teachers that share the same passion. We all care so much about teaching. So, it’s really the best academic experience I’ve ever had.”