Harry Edwards to sociology grads: Even in turbulent times, believe in yourself

May 24, 2024

Follow Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. See all Berkeley Talks.

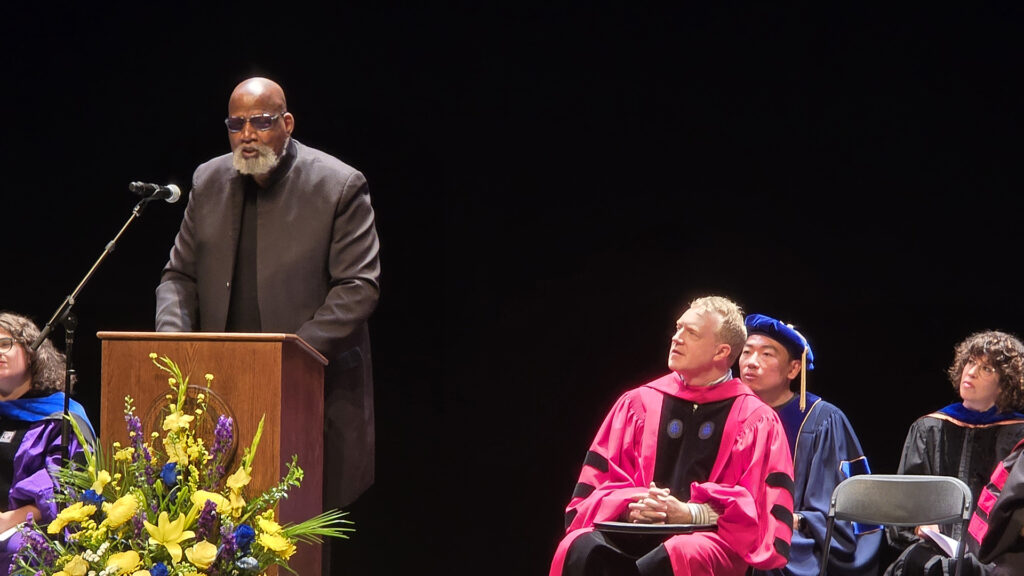

Allena Cayce/UC Berkeley

In Berkeley Talks episode 199, Harry Edwards, a renowned sports activist and UC Berkeley professor emeritus of sociology, gives the keynote address at the Department of Sociology’s 2024 commencement ceremony.

“As I stand here before you, in the twilight of my life’s time of long shadows,” said Edwards at the May 13 event, “from a perspective informed by my 81 years of experience, and by a retrospective assessment of the lessons learned over my 60 years of activism, what is my advice and message to you young people today? What emerges as most critically germane and relevant in today’s climate?

“First: Even in turbulent times, in the midst of all of the challenges, contradictions and confusion to be faced, never cease to believe in yourself and your capacities to realize your dreams.

“From time to time, you might have to take a different path than you had anticipated and planned, but you can still get there. Achievement of your dreams always begins with a belief in yourself. Never allow anyone to dissuade you of this imperative disposition. And if someone so much as even tries, you tell them that the good doctor said you need to go and get a second opinion.”

Intro: This is Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can follow Berkeley Talks wherever you listen to your podcasts. New episodes come out every other Friday. Also, we have another podcast, Berkeley Voices, that shares stories of people at UC Berkeley and the work that they do on and off campus.

[Music fades out]

Raka Ray: Well, hello everyone. It’s a delight to be here with you today to congratulate the class of 2024 and everybody else who is here in support of them. Today I get to introduce to you a man who is not only a foot and a half taller than I am, but also truly a giant of a human being in every way, Professor Harry Edwards, who was professor of sociology at Berkeley between 1970 and 2000.

Born in St. Louis Missouri, Harry Edwards was awarded an athletic scholarship to San Jose State University, completed his Ph.D. degree in sociology from Cornell, and then joined the Berkeley faculty. His experiences as an African American, as an athlete and as a sociologist helped him to keenly understand in the late 1960s that sport in America was deeply racialized and discriminatory. With this understanding, he set about transforming race relations in sports through his research, teaching, mentoring and activism.

Some of you might have seen the statues of Tommy Smith and John Carlos in San Jose State. If you haven’t, they’re great athletes, Tommy Smith and John Carlos, who won the 200 meters race in the 1968 Mexico Olympics and then raised their fists in a Black power salute. This was done because of Harry Edwards who encouraged them to do this.

He created the Olympic Project for human rights, which challenged racism in sports and called for the boycott of apartheid South Africa. Just the other day, he arranged for a personal video to be sent by gymnast Simone Biles to encourage a heartbroken 8-year-old Black Irish gymnast who had been ignored during a medal ceremony. He has used his keen sociological imagination and eye for justice to affect transformation in every sphere of sports that he could.

As professor in the department, he taught thousands of students about the sociology of sports and race, effectively creating the field of sociology of sports, even as he advised the NBA, the NFL and the major baseball league. Always a scholar and activist, he has insisted that struggle not be divorced from strategic analysis and intellectual consideration. Earlier this year, I was honored to present Harry with the Social Science for the Public Good Award for 2024. We have now renamed it the Harry Edwards Social Science for the Public Good Award. Please join me in welcoming Harry Edwards to the podium.

Do you need to adjust this?

Harry Edwards: Oh, yeah. A little bit. I got to make an adjustment here. People are vertically challenged, so I got to make up for that. Dean Ray, thank you for that gracious and profoundly generous introduction. I hope that one day soon you and I and that gentleman that you introduced will be in the same room and I’d like to meet him because he sounds like a heck of a guy.

Graduating class of 2024, families and guests, colleagues, thank you so much for this opportunity to address you on this August occasion. The problem with being the last speaker is that everything that needs to be said has been said, you just haven’t had a chance to say it, but I will try not to be too repetitive.

Today we stand again on the threshold of transformative times. Sixty-plus years ago, my undergraduate graduation was a time of exhilaration, high expectations and joy. I was a 21-year-old honors student and former scholarship athlete with the options of entering the pro football or basketball drafts, or accepting one of several fellowships to graduate school.

Strongly influenced by Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 march on Washington, I indulged the dream of helping to create a society where people would not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character, the caliber of their competence and the magnitude of their contributions to society.

But hanging over and clouding my personal excitement and aspirations was a growing concern about what was happening in society and the world around me. American society was already badly divided over civil rights issues and there was a growing division over the nation’s expanding involvement in a far-off war in a place called Vietnam, and the president was coming under increasing criticism and pressure related to both.

The trajectory of the domestic political climate had been set by the assassination of a popular president, John F. Kennedy on Nov. 22, 1963 — a tragedy that, for me, was all the more bewildering because it occurred at what was a major coming of age phase of life for me. I was a graduating honors student with fellowships to Ivy league universities, and Nov. 22, 1963 was my 21st birthday.

The tragedy was followed by a long list of others, all within the period of my subsequent graduate school matriculation, including the murder of civil rights workers Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi; the assassination of the martyred president’s brother, himself a presidential candidate; and other national leadership figures, some of whom I’ve come to know and work with personally, including Malcolm X and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., over the course of my graduate matriculation.

By 1970, in my Ph.D. graduation from Cornell, I had organized the 1968 Olympic project for human rights and protest of racial conditions in America, America’s support for apartheid in South Africa and the continuing involvement in a war where casualties on all sides were escalating and young Black men were being drafted and killed in grossly disproportionate numbers. Nationwide campus protests demanding that colleges and universities divest from apartheid South Africa had melded with what by then was a tsunami of anti-Vietnam war protest that even had disrupted the Presidential Nomination Convention in Chicago in 1968.

And most graphically, the nation’s first war with real time saturation TV coverage had brought into our living rooms the horrific scenes of religious figures setting themselves afire in front of the U.S. embassy in Saigon, of dead and wounded anti-war student protesters at Kent State, and of Black students in Orangeburg, South Carolina, killed and wounded while protesting segregation.

And again, all considered, it would seem that today we stand again on the cusp of similarly turbulent times: a society badly divided over issues of race, immigration, women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights and more.

A president under increasing criticism and pressure for both his domestic political agenda and for his policies relating to America’s involvement with, if not trending complicity, in a far off war that has spawned popular dissent, campus protest, and now an active-duty soldier setting himself afire outside of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C, all of which have exacerbated our already existing divisions as a people on the eve of what is developing through the most significant presidential election at least since 1968, if not 1860. There is even a presidential convention again being scheduled in Chicago. All of this combining to make the challenges we face today all the more explosive, convoluted, complex and difficult to resolve.

But there are critical differences. As a people we did not know about the depths and scope of human tragedy that came with the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia, or in the wake of that expansion, the horrors perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge until after these events happened. We did not know about the Rwanda genocide until after it happened. For the most part, we did not know about the scale and magnitude of 6 million-plus souls whose lives were viciously and horrifically snuffed out until the gates and ovens of Buchenwald and Auschwitz were open to the world after it happened.

But today, right now, we know about 1,200 Israeli civilian deaths, 5,100 wounded and maimed, and 253 kidnapped and initially held hostages. We know about 35,000-plus Palestinian civilian deaths, over 7,000 wounded and maimed, with thousands more buried under bombed-out rubble in Gaza, nearly 70% of them women, children and babies. We know about a burgeoning, administratively induced famine and the massive starvation in Gaza. Again, most of those threatened being women, children and babies. And these differences between now and back in my day make a difference. And if you’ve ever wondered what you would’ve done had you been around and known about the march up to the atrocities in Cambodia, in Rwanda, in 1930s Germany. Today, you’ve got your answer. It’s exactly what you are doing now.

We can be honest even when we can’t be right. The reality is that the last 75 years of this Middle East perennial conflict have taught us, attack after attack, war after war, that there is no military solution to this tragedy. The only viable resolution is for the parties involved to come together at the peace table and establish a mutually agreed-upon and sustainable peace, not just the ceasefire, not just a temporary halt for hostilities in order to get in humanitarian supplies, but a sustainable peace. Other measures simply have not worked. Occupation is not peace, and a body count is not a measure of victory.

Now, sanity compels us to concede that the only real question remaining is how many bodies each party to this conflict is going to insist upon climbing over to get to the peace table. And to this point, nobody on either side appears to even have a number in mind. The parties involved continue to forge headlong, down the same paths, employing the same bankrupt strategies and expecting different outcomes — outcomes that have only spawned more war and more violent attacks, doing the same things expecting different outcomes. The very definition of insanity.

As I stand here before you then in the twilight of my life’s time of long shadows, from a perspective informed by my 81 years of experience, and by a retrospective assessment of the lessons learned over my 60 years of activism, what is my advice and message to you young people today? What emerges as most critically germane and relevant in today’s climate?

First, even in turbulent times, in the midst of all of the challenges, contradictions and confusion to be faced, never cease to believe in yourself and your capacities to realize your dreams.

From time to time, you might have to take a different path than you had anticipated and planned, but you can still get there. Achievement of your dreams always begins with a belief in yourself. Never allow anyone to dissuade you of this imperative disposition. And if someone so much as even tries, you tell them that the good doctor said you need to go and get a second opinion.

The Founding Fathers believed in themselves, and they were not just a bunch of old dudes as typically portrayed and memorialized. When you look at one of them paintings of 1776, everybody, if they’re not gray, they’re wearing a gray wig. On July the 4th, 1776, among the signers of the Declaration of Independence creating the United States of America in the face of threats of hanging and a declaration of war from the British Empire was James Monroe, 18, Aaron Burr, 20, Alexander Hamilton, 21, James Madison, 25, and old Thomas Jefferson, 33. Don’t let anybody tell you you’re nothing but a bunch of kids and don’t know what you’re doing.

As I look at this situation today, it’s easy to see how much ageism works into our perceptions and understandings of what we are and what we’re dealing with. Don’t get caught up not only in you’re too young, but the presidential candidates are too old. I was listening to somebody the other day … Did you see Biden trying to run up on the stage? Did you see him trying to hop up on the steps of Air Force One? He looked horrible. Hey, I want to tell you something. I’m Biden’s age. I’m 81. I couldn’t run out of sight if you gave me all day.

You are not electing somebody who can run a hundred meters. You’re not electing somebody who can set a world-class time in 110 meter high hurdles. You are electing a president. We need to get over this nonsense and understand that this ageism and this ageist bias, there’s no place for that. If they’re too old, hey, guess what? Don’t tell anybody old Edwards told you that, but it sounds to me like that’s a problem that’s going to probably take care of itself. At the end of the day, get out and vote, get your friends up off the couch where they start talking about, “Yeah, we can talk about how old the candidates are,” as we go to the poll and vote. Get out and vote.

You are part of the most informed, technologically savvy and sophisticated generation in human history, you have capabilities and access to information, analysis and communications technology that in the 1960s and ’70s we not only did not have, we could not even imagine. The mobile phone that you routinely use every day puts more information retrieval analysis and computing power at your fingertips than the rocket ship that took men to the moon in the 1970s and brought them back home safely. In fact, given the volume and scope of information you need to make a habit of checking, cross-checking and verifying everything, hold to your dreams, but learn to dream with your eyes open.

Second, keep the faith, not only in yourself, but in the ideals and promises of this nation, its institutions and, most of all, the majority of the American people. They’re eminently decent, intelligent and, for the most part, value and treasure freedom.

Though controversial and dismissed in some political circles as protestor capitulation, and alternatively as pandering to protestors, it is affirming to see student protestors, counter protestors and university administrators coming together across the nation from San Francisco State and Sacramento State to Rutgers in New Jersey to discuss and debate issues of urgent and mutual concern. To paraphrase a number of university presidents and chancellors across the nation, “If we cannot come together to discuss and debate these issues even on our college campuses in an America that so many have struggled to realize and have fought and died for then that America is doomed.”

Adversarial parties, not just reaching over, but coming out from behind their barricades to sit down and discuss and debate contentious issues, is a development that speaks persuasively to the conviction that American democratic traditions and processes not only work and can be saved, but that they are worth saving.

And do not be concerned about the lack of apparent, popular political cultural leaders. We never see them coming. We never have been able to see them coming. We didn’t see Dr. King, a 26-year-old Baptist pastor coming out of Birmingham. We didn’t see Malcolm X, a 26-year-old convict coming out of prison. We didn’t see Donald, what’s his name, coming, and didn’t believe it when he got here.

This old age is something you forget. You just forget. Stay positive, you’re going to be all right. America is greater at this kind of struggle than any other nation on Earth.

Third, always cast and view societal challenges and their proposed solutions through a prism of inclusiveness.

We as a people are more successful and effective at any task undertaken when we work together, as opposed to working separately or against each other. To quote the illustrious writer and public intellectual James Baldwin and his warning in 1962 to the Civil Rights Movement, no less than America more generally, “Unless we dare to include everybody in our strategic change strategies and efforts and goals, we are doomed to realize the prophecy of those words from the Bible put the song by a slave,” and God gave Noah the rainbow sign, “No more water, the fire next time.”

And in our deafness to Baldwin’s message, between the 1962 publication of his warning and his classic book of essays, The Fire Next Time, at the turn of the decade in 1970, over 150 American cities were ravaged with fire, riots, rebellions from Watson Los Angeles to Newark, New Jersey. Episodes of lawlessness typically carried out by masses of people who felt left out and left behind by both mainstream America and a Black middle class oriented Deep South focused church-based civil rights movement.

And finally, do not be afraid.

The greatest storehouse and repository of human creativity, ingenuity and strategic solutions on Earth is in all probability the cemetery. Because far too often people are afraid to step out of their comfort zones, to take the chance of actively and aggressively pursuing their dreams and purposes in life, so tragically for everybody concerned. Ultimately, they end up taking their dreams and potential contributions to the grave with them.

And by no means should you be in fear of and immobilized by controversy. Controversy is all too often part of the deal. I heard a parent tell his daughter last week who was participating in demonstrations, protesting war and carnage, “You’re involved in something controversial.”

I was born in controversy and became even more controversial than that. You can get past it, you can get over it. Being controversial does not equate with being wrong, even when law enforcement is deployed against you. Police were sent in to break up student sit-ins protesting segregation at lunch counters and other public accommodations. In the 1960s, police were sent in to break up voting rights protests, marches led by John Lewis and others at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. Police were called on Rosa Parks for not giving up her seat on a bus and she was arrested. Police were deployed to break up many of his protests, marches and they arrested Dr. Martin Luther King 29 times. Deploying law enforcement to arrest protesters is not necessarily right or even a moral act. It is a legal act. It is an act of power, and all too often, depending upon the cause and its urgency, might still doesn’t make right.

In the broader context, we have an even greater problem with fear in these turbulent times. Fear and fear-mongering have become staples of our social political life as a society to the point that it appears that everybody is afraid of somebody. Fear the left, fear the right, fear the immigrants, fear the progressives, fear the liberals, fear the conservatives, fear the Republicans, fear the Democrats, fear the government. Fear the evangelicals. Fear the secular humanists. Fear the Muslims. Fear the Jews. Fear Black males in hoodies. Fear the rich in their power, fear the poor in their demands. Fear women and their agenda for healthcare and equality. Fear the MAGA devotees and their agenda. Fear the LBGTQ+ and their agenda. Be whatever you want to be today. But first of all, be afraid and someone it seems is always there pledging to save you from everybody and everything that you fear in exchange for your money, your loyalty, your support, your idolization and your adulation of them.

Let me conclude then with this. As I look out upon this graduating class, I am not the slightest bit hopeful that you and your generation will successfully confront and manage the challenges of these turbulent times. I am confident that you got this.

You are just that much smarter, better equipped and better prepared than any other generation in American history. Now, at this commencement, as you start your journeys into the rest of your lives, as an old scholar-activist and UC Berkeley professor, I feel certain and completely convinced that the struggle to form that more perfect union and to create a better world is in good hands. And I salute and applaud you. Congratulations, best of luck and Godspeed.

Outro: You’ve been listening to Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. Follow us wherever you listen to your podcasts. You can find all of our podcast episodes, with transcripts and photos, on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

[Music fades out]

Watch a video of the Department of Sociology’s full commencement ceremony.