Carol Christ: Years of challenge, years of historic progress

In an interview before her retirement, the UC Berkeley chancellor reflected on the social turmoil of her years in office, the values that have guided her — and the essential lesson she learned from students.

Keegan Houser/UC Berkeley

May 28, 2024

One might expect that a leader, just weeks before retirement, would be quietly winding down. But for UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ, campus turmoil arising from the Hamas-Israel conflict and a looming budget shortfall have left little time for celebration ahead of her departure at the end of June.

It’s striking that Christ’s last weeks have been so much like her first weeks. She moved into her California Hall office in July 2017 and was immediately forced to deal with a debilitating budget crisis and an ongoing federal probe of sexual harassment on campus. The school was still reeling from the winter riot that had canceled a talk by right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, raising questions about support for free speech at Berkeley.

In the ensuing years, she’s had to confront the challenges presented by other controversial speakers, the COVID pandemic that shut down in-person classes, wildfires that covered the campus in smoke, a strike by graduate student workers, and the drive to build desperately needed student housing, which included the closing and preparation of People’s Park for development.

There is broad agreement that Christ navigated these crises with acumen and concern for the community — advancing solutions, often through collaboration, dialogue and compromise. While headlines often focused on the tumult, she and her leadership team achieved historic progress on student housing, fundraising and expanding Berkeley’s commitment to innovation and entrepreneurship.

In an interview with Berkeley News, Christ talked about the challenges she has faced leading one of the world’s most influential universities, the values and experiences that guided her, and the critical lesson she has learned in a career spent with students.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Berkeley News: When you think of Berkeley in the time that you’ve been here — since you arrived in 1970 — what are the most significant changes you’ve seen? Also, what has remained constant?

Jane Scherr/UC Berkeley

Chancellor Carol T. Christ: Well, Berkeley is certainly much bigger now than it was when I first came in 1970. It has 43,000 students now, and I think it was under 25,000 students then. So that’s a change.

Berkeley was largely a white institution when I came, and now it’s an extraordinarily diverse institution. So that has changed. When I joined the faculty, only 3% of the faculty were women. Now it’s about a third.

Many things have stayed the same. I think that campus would be recognizable to someone whose last experience of it was in the early 1970s. The structures that define it — Sather Gate, the Campanile.

What’s also the same is that Berkeley sees itself — to use (incoming Chancellor) Rich Lyons’ phrase — as a place for changemakers, whether it’s scientific change through the discovery of extraordinary things like new elements, or political change, like the Free Speech Movement or the Third World college revolution. That Berkeley is a campus in which people think they are defining history, and they indeed are defining history. That hasn’t changed.

I can’t help but notice that your time in office has coincided with a time of incredible turmoil and turbulence in our society — threats to democracy; tensions over civil rights, social justice and free speech; environmental crisis; and the COVID pandemic. Even massive change in collegiate athletics. How has all of this changed the Berkeley campus?

A number of the crises that the campus has experienced during the time that I’ve been chancellor have made us feel more fragile, more socially isolated.

I’m thinking, in particular, of the wildfire, the smoke events. I’m thinking of the loss of power on the campus. I’m thinking, of course, of COVID. I’m thinking of the political turmoil.

Irene Yi/UC Berkeley

There is less a sense of a world that has clear and commonly-held culture markers and boundaries. In general, that has made people feel more anxious, more unmoored, more socially isolated. In large part, this has been COVID, but it’s also everything else that has happened over the last seven years. It’s been a turbulent period.

Did you ever find yourself thinking, “Wow, how am I going to tame the whirlwind here?”

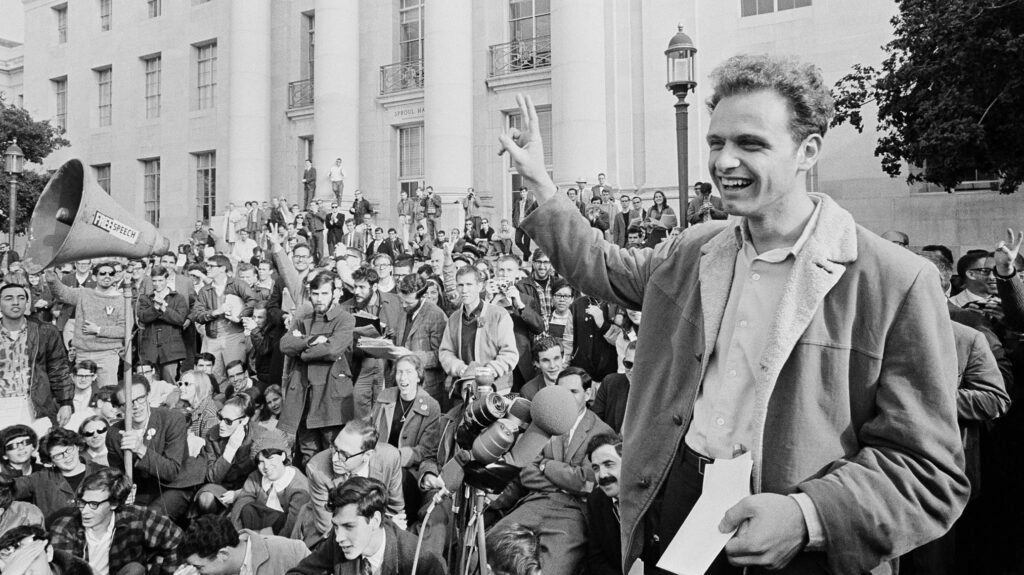

Oh, of course — I think about that all the time. I certainly came in with a crisis of that sort with free speech, and what I thought was the necessity of showing the world that we could host conservative political speakers. But it’s ending with a crisis of free speech, too. You can see the pictures on the wall of my office of the Berkeley free speech crisis of 1964. That’s been very much a defining issue.

Associated Press

In this period at Berkeley, but also in the wider world, it’s been a time of tremendous polarization, an almost organic process of sorting into opposing and antagonistic camps. Has this polarization affected the campus culture? And does it worry you?

It worries me a great deal. I think that’s the biggest challenge that we face, both within the campus culture, but also in our wider political world: We’re losing the capacity to talk across differences. That’s so important a capacity to have, it’s so important to be able to talk civilly with people whose opinions are very different from our own, on whatever subject you choose.

Why is that such a struggle at this moment?

The whole campus is so much more contentious, just like our society is contentious.”

It’s a struggle because we’ve lost the sense of a consensus narrative for the events that we’re experiencing in the world. I often recall that when I was in graduate school, I used to watch Walter Cronkite every evening, and he would end every show, “That’s the way it is, May 13th, 2024.”

Today, there’s nowhere you can go to hear somebody say that. And in fact, news media is so splintered now that you can find a news outlet that reflects your own opinions and beliefs. So there is not a sense of a shared reality anymore. And that makes it difficult to have a conversation.

Let’s talk about leadership. You’ve had to navigate various external crises, but you’ve also had to steer the university through financial crises. You’ve tackled the issue of student housing and made a lot of headway. People’s Park has moved forward — against much friction — but as a leader, you moved it forward. Has there been a guiding strategy or principle that you followed in addressing these challenges?

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

One that is so important is building a team. During COVID, for example, we organized quite an elaborate set of working groups, each of which had a chair, and the chairs met frequently. We divided up the work, but we made sure there was a lot of communication among workstreams.

I’ve tried to build a very strong team in my cabinet, and that’s really helpful. A lot of people have the mistaken idea that being the chancellor or the president of a university or college is like being a CEO. It’s nothing like that. It’s like being the mayor of a very fractious, complex city.

What you need to do to succeed at a job like that is, first of all, have good listening skills. You bring people together who feel that they’re stakeholders, and whatever issue you’re dealing with, listen to them carefully.

But you need to build teams that are able to address issues in the complexity they have in a university like this one.

How important is your own personal sense of resolve in this dynamic of decision-making, in pursuing progress?

A sense of resolve is enormously important. I think one of the most important attributes of a leader is decisiveness. I don’t mean decisiveness in an arbitrary way, like you just decide things without ever talking to anybody. But the ability to reach a decision, the ability to reach a decision in a prompt way, even if it’s not the best possible decision, is better than no decision at all.

One of the worst qualities of a leader is to be either indecisive and unable to reach a decision, or be someone who reaches a decision and then takes it back the first time they hear spirited opposition to the decision that they’ve made. Sometimes it’s hard to stay the course, but it’s important.

Have the demands of leadership changed over the past few decades?

When I first started doing administrative jobs in the late 1980s, you got your mail in a folder in the morning. Someone had opened it for you. Someone had maybe put some notes about how they thought you should respond. You slowly went through your mail, and then you talked to your chief of staff, explained how you were going to answer each piece of mail. Then somebody would draft an answer. You would OK the draft, and it would be prepared for your signature. You would sign the letter.

This whole process took more than a week! That’s so different from the world now — I get hundreds of emails a day, and people expect an answer in usually less than 24 hours.

In the 1970s at Berkeley, there was no expectation that the chancellor was involved significantly in fundraising. Generally, we were generously supported by the state. Now, fundraising is probably the biggest part of my job.

The whole campus is so much more contentious, just like our society is contentious. Many more groups feel a sense of very particular identity and want that identity to be recognized and welcomed by the university. So it’s a much more diverse place with a more contentious community.

Entrepreneurship was not a big piece of the university back in the 1970s. Now it’s exploding, and it’s so dynamic.

Can you identify one decision you made in your time as chancellor that was the most meaningful or momentous?

Gosh, it’s really hard to say there was just one decision. Probably it would be to proceed aggressively with building housing and, perhaps specifically, to build on People’s Park. That would probably be the most momentous decision.

LMS Architects/Hood Design Studio

Can you think of the moments in your time as chancellor that really stand out — whether they’re big or small, whether they’re wonderful, whether they’re difficult or sad?

One time early in my tenure as chancellor was when I was in the big conference room, 200 California Hall, when we were trying to protect Ben Shapiro, a very conservative speaker, and his right to speak on campus. We were sitting there with the emergency operations team deciding, minute by minute, what we were going to do.

The park had been defined by the revolution that created it for over 50 years. And people were, I think, frightened to touch it, even as it had very badly disintegrated and was becoming a real danger to both the people who lived in the park and the people who walked around the park, the neighbors.

Other moments — I guess I have to say the Big Games that we won, don’t I?

The decision to move to the ACC (Atlantic Coast Conference) was another big moment. We were very much bound to Stanford in that decision — and that was an important one.

I think the decisions in relationship to the encampment (the pro-Palestinian encampment outside of Sproul Hall) have been important, the decision to not call in the police as long as the encampment was relatively peaceful, to let it stay.

You’ve talked a lot about free speech — in the Free Speech Movement now 60 years ago, and from that to Milo Yiannopoulos, to Ben Shapiro, to the pro-Palestine encampment. I wonder whether you’ve gone through these experiences and come away with any sense of discouragement. Have you lost any faith in the Enlightenment-era ideals and models of how free speech works in a society?

Hulda Nelson/UC Berkeley

My views about free speech have changed — they’ve deepened, in the sense that I believe it’s important to exercise your right of free speech in the context of our principles of community. I don’t think I would characterize myself as losing faith. I feel as strongly as I ever have that free speech is essential for the formation of political opinion in a democracy.

It’s almost an absolute, but not quite, because there are things that are not protected by free speech, like yelling, “Fire!” in a crowded theater. But it’s important that people also think about the principles of community. Just because you have the right to say something doesn’t mean it’s right to say.

I don’t think that people should be shouted down. I think people have the right to speak, but they also need to be able to listen to the arguments against whatever they have spoken.

In all kinds of contexts, you choose what you say, and you choose for all kinds of reasons.

So I would defend absolutely the right of free speech as very important to a university community, very important to a democracy. But that doesn’t mean that it should be a free-for-all, and that everybody should, you know, say anything that comes into their mind on any occasion whatsoever.

If you value a community, you have to value the things that are appropriate to the communal context in which you’re interacting.

I also think that social media has changed free speech. I mean, John Stuart Mill, this idea of the free marketplace of ideas — that with free speech in the marketplace of ideas, the truth would always win out — we no longer have the free marketplace of ideas. I think we have dozens of little isolated boutique shops of ideas, and they don’t interact a whole lot.

How do you answer a critic who says, “You know, it’s right to have controversial speakers here — left, right, whatever position. But we’re living in a time when anti-democratic ideas are getting traction, they’re spreading, they’re becoming a real threat. There’s corrosion from those ideas, and we see it in our society every day.”

What I say is, someone making that argument has a rather short memory of history. There have been lots of times in history in which there have been controversial, indeed hateful, ideas. Think about the civil rights movement, for example, not that long ago. Think about the Japanese internment during World War II.

As you get older, you start to understand the limitations of what any one person can do. … You understand just how hard it is to create change.

I believe the only way you confront hateful and dangerous ideas, the only way you confront bad speech, is with good speech. I believe speech is the answer to bad ideas. I don’t think that people should be shouted down. I think people have the right to speak, but they also need to be able to listen to the arguments against whatever they have spoken.

You said in one interview recently that one thing you won’t miss when you retire is angry protests. Can you elaborate on that? It seems like there might be an element of frustration there.

When you’re the chancellor, angry protests are often directed at you, whether you have anything to do with the issue or not. So it’s difficult — you have to work hard as a leader not to personalize things. It’s really important to say, “This isn’t about me, Carol Christ, who I am as an individual. This is about anger at the institution for some value or stand the institution is taking that these protesters disagree with.”

That takes a lot of personal strength.

Yeah, it does.

We started the interview with a question about what’s changed since you first came to Berkeley. And I want to circle back to that, to ask specifically about students. Have they changed since 1970?

Oh, yes, of course. The student body is much more diverse. They are digital natives. So they are so at ease with this digital world in which we live. They’re really media savvy.

Keegan Houser/UC Berkeley

They’re more anxious than the students were in the 1970s, when I began teaching. They just feel it’s become so competitive to get into a fine university like Berkeley. They have pushed themselves so hard in high school. They don’t know how to stop pushing themselves and to really enjoy and learn and take this moment for everything it can offer them, independent of this anxious desire to excel and to please another.

As you leave office, are there any lessons you’ve learned from students that you’re likely to hold in mind as you move on to your next chapters?

I think what you learn from students is, first of all, the time of life they’re in is so exciting. They come with such an ambition that they can change the world. I just had an appointment with a student earlier this afternoon. He’s an out-of-state student. And he said, “I chose to come to Berkeley because I thought it would give me a good position from which I could change the world.” He’s passionate about climate change — that’s his issue.

That’s something to remember, because as you get older, you start to understand the limitations of what any one person can do. You come to understand the complexity of the world. You understand just how hard it is to create change.

And so what I always take from students is that belief: “I can change the world, I can make a difference.”

You have argued that one of the most significant things about literature is its capacity for building our empathy, building our ability to hear and understand people outside of ourselves. Do you think that we as a society are suffering a deficit of empathy today?

That’s a very wise question — I think you’re right. I do think that there’s an empathy deficit, and it’s so important to be able to put yourself in somebody else’s shoes, to look with somebody else’s eyes. It’s one of the things that reading literature gives us, because literature is fundamentally about character, and about character in the course of events and time.

If you were able to put a big dose of empathy in the water so that everybody got an infusion of it, what impact might that have?

I think it would make people less angry. It would make people less anxious because it would provide a kind of way forward. But most important is that it would make people less angry.

Last question: Let’s spin forward 50 years. What do you think is likely to remain constant at UC Berkeley? And what are some of the changes that the institution might expect? I realize it’s a big question …

It’s a really big question, and I’m not sure I could have, in 1970, foreseen the next 50 years of changes.

But I think that what will stay the same is Berkeley’s commitment to educating students and its commitment to creating new knowledge. That’s the DNA of this place.

What I think will change is that our educational structures are going to become more flexible. They’re going to rely more on AI, for one. They’ll rely more on the digital communication of knowledge, so that education is going to become more portable.

And I hope that it can adapt better to serve people whenever they need education in their lives, rather than always thinking of it as these four years between 18 and 22.