Berkeley Talks: Adam Gopnik on what it takes to keep liberal democracies alive

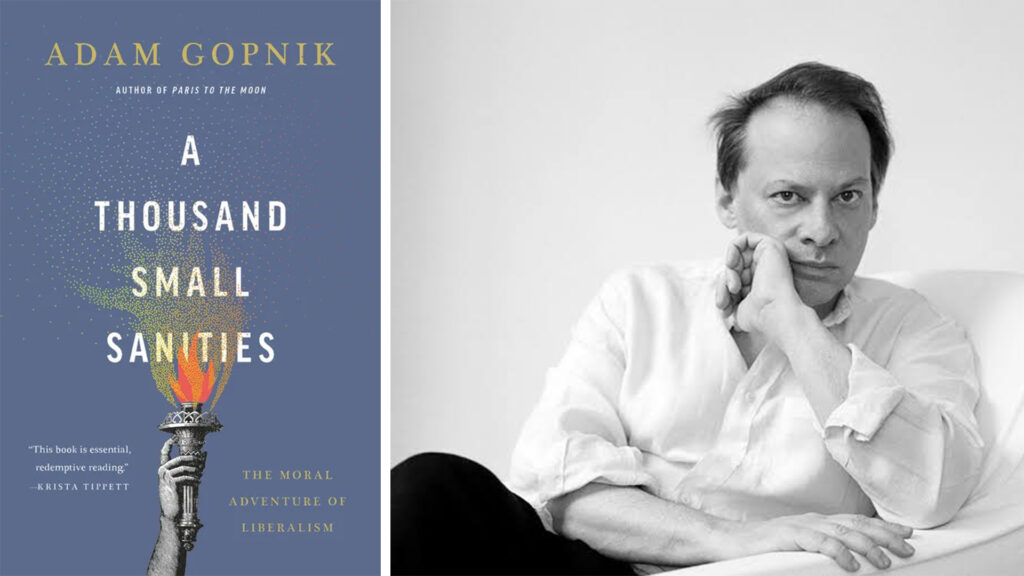

“What makes liberalism distinct is a perpetual commitment to reform,” says the New Yorker writer and author of A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism.

June 14, 2024

Follow Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. See all Berkeley Talks.

Courtesy of Adam Gopnik

In Berkeley Talks episode 202, New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik discusses liberalism — what it means, why we need it and the endless dedication it requires to maintain.

Liberal democracy, he said at a UC Berkeley event in April, depends on two pillars: free and fair elections and the practice of open institutions, places where people can meet and debate without the pressures of overt supervision.

Gopnik said these spaces of “commonplace civilization” — coffeehouses, parks, even zoos — enable democratic elections to “reform, accelerate and improve.”

“These secondary institutions … are not in themselves explicitly political at all, but provide little arenas in which we learn the habits of coexistence, mutual toleration and the difficult, but necessary, business of collaborating with those who come from vastly different backgrounds, classes, castes and creeds from ourselves.”

And what makes liberalism unique, he said, is that it requires a commitment to constant reform.

“People get exhausted by the search for perpetual reform,” he said. “But we have to be committed to reform because our circles of compassion, no matter how we try to broaden them, come to an end.”

So it’s up to each of us, he said, to always refocus our attention on the other, to re-understand and expand our circles of compassion.

This April 24 event was sponsored by UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities and made possible by the support of Humanities West, San Francisco.

[Music: “Silver Lanyard” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Intro: This is Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can follow Berkeley Talks wherever you listen to your podcasts. New episodes come out every other Friday. Also, we have another podcast, Berkeley Voices, that shares stories of people at UC Berkeley and the work that they do on and off campus.

[Music fades out]

Stephen Best: So I think we’ll get started. Hello everyone. Welcome to the Townsend Center. The Townsend Center is very pleased to host Adam Gopnik, one of the most brilliantly perceptive critics of art, food, and music, Paris and New York, liberalism in the humanities, Balzac, Victor Hugo and of course Proust. We would like to thank Humanities West San Francisco for helping to bring Adam Gopnik to the Bay Area and to the Berkeley campus.

Adam Gopnik has been a staff writer at the New Yorker since 1986. He is a three-time winner of the National Magazine Award for Essays and for Criticism, as well as a recipient of the George Polk Award for magazine reporting and the Canadian National Magazine Award Gold Medal for arts writing. 10 years into his tenure at the New Yorker, Gopnik famously left New York to live and write in Paris, where he wrote his Paris Journal for the magazine over the next five years.

Those years abroad resulted in one of his most acclaimed works, Paris to the Moon. Personally, I was propelled to move to Paris in 2012 by James Baldwin’s, Notes of a Native Son and other essays and what Baldwin described as the silence he encountered in Paris. For him, a silence born of the fact that he did not initially speak French, but for both of us a desire to escape the cacophony of America’s racial drama.

For me, Paris to the Moon was a bit of a cautionary tale, a reminder not to be lulled by visions of Paris as some out-of-this-world magical place. One finds oneself both stunned and humbled by the broad sweep of Gopnik’s intellectual imagination. Other writers often note the eloquence and wit, brilliance and erudition of Gopnik’s writing, his ability to predicate a deeply philosophical line of thought on the everyday moments that define our lives.

I think of you walking past the etching I believe in a Paris window. Yeah, just that. His ability to do that. His contributions to literature and journalism have solidified his status as one of the most important thinkers of our time.

Gopnik’s most recent books include All That Happiness Is from 2024, which argues for the value of accomplishment, a kind of self-directed absorption in a task over an externally imposed sense of achievement. The real work on the mystery of mastery in which he explores the question of how people develop extraordinary skills the mastery of a craft from drawing a nude to driving instruction to think of that as a craft is quite brilliant.

And anticipating today’s occasion A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism from 2019, a book written in the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election in which Gopnik offers a stirring defense of liberalism against the rise of authoritarianisms in our time.

In recent years, Gopnik has written several pieces for the New Yorker on liberalism, American institutions, and the structures of liberal democracy that protect free debate, fragile architectures that are in no way guaranteed and currently require our urgent defense. Even Gopnik’s recent review of the historian Timothy Ryback’s book, Takeover: Hitler’s Final Rise to Power, on Hitler’s establishment-enablers and the week-by-week, day-by-day banalities of the year 1932 is written in the spirit of this defense.

The ever-present threat to liberalism is the topic of today’s talk, the national emergency on liberal institutions protecting pluralism and free debate. Please join me in welcoming Adam Gopnik to the University of California Berkeley.

Adam Gopnik: Thank you. That’ll be the point so that’s it. Thank you. Thank you. What a beautiful introduction and over-generous. I’m delighted to be here today more than I can tell you. When you referenced me as one of our leading thinkers you may have heard my mother laughing in the front row, but I’m delighted that my parents, both retired professors, Professor Irwin Gopnik, Professor Myrna Gopnik are here this afternoon to listen and I’m sure to ask tough questions afterwards. If I have any ability to be eloquent or articulate it’s from fighting my way past six siblings at the dinner table every night for 20-some years.

I want to talk today, yes, about liberalism, about liberal democracy. As was suggested, my arc, my life as a writer is in some ways a classic one of a reformed esteem. I spent most of the first 20 years or so writing for the New Yorker, writing about Paris and food and art, domestic manners, but as happens to us, I think in what I will call decorously middle age, we become aware of the world around us in ways that are disturbing, upsetting, significant, and our minds broaden and our vision focuses and mind focus to some of you may know from reading my work on the issue of incarceration in America. I wrote a very long piece, I think reasonably early on called “The Caging of America” about that issue, then again about gun sanity in America.

I’ve had the tragic duty of being the New Yorker‘s man every time we have yet another gun massacre in America. They asked me to write exactly the same piece that I’d written the previous time about it, and I never regret doing it because those same lessons apply and in recent years, exactly as you’ve been saying, I’ve been turned towards the broader questions of the superintending architecture, if I can use a slightly pretentious term of liberal democracy, and what makes it work.

I’m now also the magazine’s regular writer on the philosophy of liberalism. I have three subjects — gun sanity, guarantees of liberalism and the quarterback of the New York Jets who will usually arrives from California and always fails. Those are the three subjects on which the magazine always has me writing. The thing about liberalism is that it is in its nature a somewhat incoherent category and it’s also a word that’s used in so many different ways that it’s in many respects banished from our popular discourse.

When I wrote my book, A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism, I made, as authors do, a tour of select parts of the world, and in each place, I was discouraged from using the word at all.

On a Sunday morning talk show, my host urged me not to say or use the word “liberalism” because that meant to his audience Obama and Hillary Clinton, to please say “liberal democracy” because that would include Mitt Romney and John McCain. I obeyed. Crossing the border into Canada, I was encouraged to use the word “liberalism,” but never to use the word “liberals” because that references the governing party of Canada, the Liberal Party of Justin Trudeau and praising liberals would seem to be praising the long-term party in power. If you go to London when the book was published, you’re asked not to reference liberals because that reference is a now defunct and pathetic political party in a largely finished political movement.

And of course, as any of you will know who have spent time in Paris, liberals and liberalism in Paris and France refers only to free enterprise Thatcherians because of the peculiar evolution of the language. So you are urged never to say liberalism, liberals or liberal, but to say republican, democratic and republicanism.

Only in Italy does the word seem to be valued. When my book A Thousand Small Sanities was published in Italian, they called it Il liberalismo e l’amore — Liberalism and Love — which I thought was an absolutely beautiful name for the book and made me wish that I had thought of that for the book in English. And then I realized that every book that’s published in Italian uses that formula. You write a book about high-energy physics, it’s called Fisica e amore. That’s been true about three of my books so far have had “amore” attached to them.

So it’s a complicated concept. It’s a concept that’s had in some ways very rich, but a very treacherous life in the world of ideas, in the world of concepts, and certainly in the world of words. When I think about the idea though, I always come back to a very simple articulation of it, and that is that liberalism depends on two pillars.

One obviously is the idea of free and fair elections, the practice of democracy, but we recognize that that in itself isn’t sufficient because we know perfectly well that most liberal democratic countries, to use the term of favor of my talk show host, we know that most liberal democratic countries have only had something like true democracy or an approach to it in very recent years.

We know that about this country, we know about the fight to have something like democracy in America, which dates to in my own lifetime. I can remember watching Bayard Rustin and Martin Luther King on the television screen. At the same time, the other pillar of a liberal democracy, which enables those often inadequate democratic elections to reform, accelerate and improve is what we call, for lack of a better word, liberal institutions, open institutions, places where people can meet and debate without the pressures of overt supervision.

And that’s why in my book, A Thousand Small Sanities, I chose as my eureka moment, as my primordial moment, so to speak, my big bang moment, a moment with John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor in the 1830s in London.

John Stuart Mill, already a major philosopher thinking hard about questions of freedom and of the individual and of society met the great love of his life, Harriet Taylor, whom he always described as his greatest teacher and was certainly his greatest collaborator, but who then got what one might call Yokoized by respectable male commentators, deprecated and diminished until very recently when we’ve come to understand what a major mind Harriet Taylor really was and they struck up a love affair.

It was a very bound-about compromised love affair because she was married with three children, but they had a passionate attachment to each other intellectually and erotically, but they would always meet on the bench outside the rhinoceros cage at the London Zoo because with the acuity given only to philosophers, they recognized that everyone would be looking at the rhinoceros and no one would be looking at the couple canoodling on the bench by the rhinoceros’ cage. And I chose that as my primal, my primordial moment exactly, because it seemed to me that it was a crucial moment of hybridization of ideas because John Stuart Mill, of course, was working on the ideas and on the rhetoric that would eventually blossom as his great book of 1859, On Liberty, still a foundational volume of liberal democracy preceding the Great Reform movement within Britain and within the British Parliament in which Mill sat for a while. A book, On Liberty, that is still the foundational declaration of the absolute right of individuals to speak freely without prior constraint, without government censorship, without the interference of the church.

It is still the greatest testament of the power of free speech and open debate, not only to allow us to arrive at better and more rational social plans, but also to enable us to seek our own individual fulfillment, which was a crucial idea for Mill. It wasn’t enough to be free to argue about ideas. You had to be free to listen to Mozart, to write poetry, to find yourself as he did in France as many of us have done after him. At the same time, Harriet Taylor was rooting on brewing up the ideas that would become her great book published under both their names on the subjection of women, which is if not the first still perhaps the most powerful and enraged indignant case made, not for women to have more authority and more freedom than they had at that moment in the 19th century.

But to be treated on terms of absolute equality with men not asking for a favor, so to speak, but demanding absolute equality in business, in work, in politics, and in every sphere, making the good point that in every sphere, I still think this was an immensely shrewd argument that in every sphere, the limited ones where women were allowed to compete as in writing novels or acting on the stage, they were clearly superior to the men who they competed with this in the great age of Ellen Terry and George Eliot.

Now we tend to think of those two impulses of those two movements as being in some ways contradictory. People will say that over and over again. They’ll say that the urge towards individual liberty and the rights of free speech and free expression are in some way intentioned with or even opposed to the drive for social equality and the push for the fair treatment of minorities or in the case of women of majorities previously suppressed. That those two things are perpetually intentioned.

I think that the image and the instance of Mill and Taylor meeting on that rhinoceros bench and collaborating together, it’s good empirical proof or argument that it isn’t because exactly their insight, their shared insight in front of that squat and unappealing rhinoceros was that these two things were in perfect harmony. That the urge to speak freely, to feel freely, to find yourself on your own terms, not dictated by power, was essentially allied to the desire to spread that kind of freedom, to spread those rights as broadly and as universally as you possibly could.

Mill could not be fulfilled in himself if Taylor was in the state of perpetual peonage. It’s an idea that’s still summed up beautifully by Bruce Springsteen at the end of every concert. If you’ve ever been to a Springsteen concert, you’ll know that he ends it, excuse me, by saying, “Nobody wins unless everybody wins.” It’s a simple striking meme and it sums up exactly what Taylor and Mill were feeling and beginning to articulate on that bench outside the rhinoceros cage at the London Zoo. I use the rhinoceros in that book as for me, a symbol of the power of the kind of liberal thought that John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor were moving towards. Exactly because it looks awkward when you first pay attention to it. It doesn’t have any of the dogmatic clarity of Marxism on the one hand or of Catholicism on the other hand. It doesn’t offer you a neat eclipsed version of history.

It offers you a range of possibilities, explorations, investigations. Like the rhinoceros, it’s far from ideal and when we examine it can seem baggy and squat and unappealing as we often feel, as we inevitably feel when we examine the workings of a liberal democracy in our own lives today and yet its enormous attribute.

The one thing that the rhinoceros has is that it’s real. The rhinoceros is the original type of the unicorn. Travelers would go off, see a rhinoceros, and come home and draw a unicorn because it looked much better with silver skin and one perfect horn in its head. Unicorns are non-existence. Rhinoceroses are real, and in that sense, I think a powerful symbol of the radical realism that Mill and Taylor shared on that bench.

Now, I’ve said that to my mind the two pillars of liberalism properly understood of liberal democracy as we engage in it are on the one hand free and fair elections and on the other the practice of open institutions.

Now, usually, when we think of open institutions, we think of a place like this one. We think of universities, we think of libraries, we think of parliaments, we think of all the educational and argumentative institutions of a modern society, and obviously, they make an enormous difference and obviously they are significant, but I think the hidden part of those liberal institutions, so the less obvious one, is exactly not just what they were arguing about at the zoo, but the very fact that the zoo exists as a public institution. Officially apolitical or nonpolitical, and yet a place exactly where people can meet and clandestinely or openly talk, share ideas, arrive at new visions, new love affairs, new conclusions. That in itself I think is a hugely important part of this story.

That is that the real strength of a liberal democracy does not lie just in or even primarily in its formal arrangements for fair elections or in its sustaining formal institutions of open debate and discussion. It rests much more on all of the kind of invisible institutions, all of the public gathering places like a zoo where we can have debates, contact conversation with those who are not of our class and kind, but where we learn the habits of tolerance, of engagement, of mutual coexistence that are more than anything else, if you like the emotional and moral underpinning of a liberal society. Let me tie my shoelace and then move on.

These are of course new shoes that my wife insisted I wear in place of the sneakers that I normally have. It is her claim and that of my wonderful daughter to whom the book A Thousand Small Sanities is addressed and dedicated that I have the unfortunate habit of appearing dressing like a 1980s stand-up comedian when I’m giving talks in jeans, a jacket and sneakers, and they say that this is a look that has long since been banished.

Let me give you an example. Let me try and give you a historical example that I’ve written about often and enthusiastically to help you see what I mean about the role of non-political institutions and making political progress and making political progress possible. And the one I always come back to is that of Frederick Law Olmsted and the design and the execution of Central Park in New York City. Very few people know surprisingly that Olmsted was, before he designed a square inch or acre of park land, was a magazine writer and a newspaper writer.

I see some nodding heads here, so you were ahead of me in this. He was sent by the then brand new New York Times to the southern states of the United States to write a report on enslaved people and on the slave states, and he had one totally original insight, and that was that he saw that the catastrophe of slavery was not only in its cruelty and it’s being an intolerable human arrangement, but that it’s utterly stultified and paralyzed all the society around it, creating a kind of concentration camp civilization that had none of the qualities of modernity, if you like, of progress, of mutual engagement that he experienced in the North.

Has realized that the thing that he was missing most in his sojourn in the South were fireworks displays, amateur opera societies, baseball teams, all of the ways in which people in a more free society than the one he was experiencing come together outside their normal clans and kinds and learn how to interact with each other, learn how to live alongside each other.

And Central Park for him the design of Central Park turned on this idea. It was meant to be a kind of green parliament. It was meant to be an open space where political conversation as such might or might not take place, but the deeper underpinning of democratic politics that is shared experience of profoundly different kinds in a common space would go on. It’s one of the reasons why Central Park, if any of you are New Yorkers or know it, I’m blessed to live not too far from it and to walk through it every day. It’s one reason why there’s no Grand Allée in Central Park as there is say in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris or in London parks. It isn’t a piece of greenery that’s been conserved or preserved. It’s a painting. Every single blade of grass, every single tree, every rock in it has been designed and laid in to create an effect.

An effect that kind of background painting of democracy, and it was exactly in the notion that people of very different kinds would come together and play in the park that Olmstead brilliantly thought that you would have a stronger foundation for democracy and liberty in New York for a healthy politics. And Olmstead came up with a beautiful simple name for the power of these kinds of institutions, which extend to coffee houses and to amateur musical groups as I said. He called them commonplace civilization. Commonplace civilization. And he said that a society can only be as strong as the commonplace civilization within it. And he meant by that as I say, all of those secondary institutions, zoos, parks, coffee houses that are not in themselves explicitly political at all, but that provide little arenas in which we learn the habits of coexistence, mutual toleration and the difficult but necessary business of collaborating with those who come from vastly different backgrounds, classes, castes and creeds from ourselves.

Now, what’s so interesting about that is that Olmstead’s insight is one that has been reiterated and reaffirmed by every generation of social science that has common sense I’m sure you’ve all heard the name of Robert Putnam. He became famous as a Harvard sociologist. He became famous in the 1990s because he wrote a bestselling book called Bowling Alone about the decline of bowling leagues in America, which he used as an example of the degradation or the corrosion of that kind of social capital of that commonplace civilization as Olmstead had conceived it.

And what’s fascinating about Putnam if you study him, is that he did his crucial work in Italy, his crucial work as a social scientist. And he asked the question, what makes democratic decentralization work in a country like Italy? Italy was going through a moment when more and more decision-making was being moved from the center in Rome to the periphery, so to speak, of the regions and the towns and trying to evaluate the places in which that democratic decentralization worked, seeing how sound it was, how satisfied people were with it at all.

He discovered that by far the most powerful correlation to predict the success or failure of a democratization, regional democratization was the number of amateur opera groups that you had in the towns. Exactly, and all those other kinds of social capital, all that other secondary commonplace civilization because it was people who had already learned the difficult but essential habits of cooperation, coexistence, working with others, not of your caste or kind, who had the base things of democracy, so to speak, already imprinted in their minds and souls and bodies and only had to activate it to bring it to the world of urns and debates.

That’s an insight that’s been repeated over and over again, that the primary importance of social capital, what we call after Olmstead “commonplace civilization,” not only in decorating, embroidering democracy, but in sustaining it, irrigating it and watering it. That’s a truth that seems to have been reaffirmed again and again by the social sciences, by history and indeed by our own personal observation.

Now, I hardly need say to you that we are living in a moment of crisis, both for the practice of free and fair elections and for the open liberal institutions that we readily recognize — universities and libraries, and also in perhaps not least significantly in the practice of that commonplace civilization in the small, the [inaudible] political places that allow politics to happen. We all feel that I think. I wrote a piece for the New Yorker, an essay for the New Yorker just a few weeks ago, trying to respond to the urgency of that that was in effect kind of an allegorical fable.

I wrote about 1932 in Germany about the ascent of Hitler to power, and though I never once mentioned, I was drawing on Timothy Ryback’s fine new book on that subject, but also on all of the social science and history I could find peripheral to it that would inform my understanding of that year in that moment. What was scary, and I never mentioned once contemporary politics or the former president or anything else by name, and yet everyone who read it recognized frightening and clear parallels with what we are going through now.

And I wanted to do that, not because there are sort of facile parallels to be made between Trumpism and Nazism. That’s not the point at all. It’s to reaffirm something that historians like Timothy Snyder and my friend Ruth Ben-Ghiat have been telling us over and over again in the past few years, that is that democracies die in predictable ways just as when with the ideology, the evolution of cancer from a melanoma to stage four is in many respects predictable.

There are predictable patterns in the destruction and dissolution of a democracy, and one of those patterns is exactly that you begin to see the corrosion of not just of the official constitutional side of a liberal democracy, but exactly of those underpinnings and all of the premises what are sometimes called, I think a little unfortunately, the norms by which a democracy works, and we feel it, too, in the corrosion and in the erosion of our commonplace civilization, of our ability to meet, gather and understand each other.

I don’t mean in any sense to exempt liberals in the other sense that is people like myself and perhaps many of you in the audience who tend to fall on the left side of the political ledger. I don’t mean to exempt us from responsibility for some of that corrosion. I think it’s something that we have to self-examine and look at. I had the experience of going to Akron, Ohio, to speak at the University of Akron not too long ago, a couple of years ago. And one of the things that I got instructed on by the people who were there was exactly how corrosive the globalization of the rubber industry had been to the commonplace civilization of Akron. Akron had been a living and lively small metropolis, the Goodyear plant closed, and the entire inner, not just the economy, but the thriving culture of the place collapsed around it.

I like to quote rock stars when I’m speaking. As you’ve noticed, I quoted Springsteen, the best account of the decline and collapse of the commonplace civilization of Akron is in Chrissie Hynde’s memoir. Anyone remember Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders? I thought Chrissie Hynde was British because The Pretenders were a British band.

She’s actually from Akron and she writes eloquently and beautifully and alarmingly and warningly about how when she was growing up as a girl, Akron was a place where there was an underground record store, the three underground record stores, small rock bars, department stores, movie houses or repertory movie house, all of the places where you could get in effect an education exactly in the commonplace civilization that enabled her to discover punk, learn rock and roll, and eventually get out and go to England. All of that vanished and destroyed now.

So I certainly recognize the degree to which liberal democracy creates its own acidic forces and creates its own corrosion, but I don’t think that’s the primary crisis that we’re facing right now, and I’d be disingenuous if I said that it was. I think it is one of the crises and one that we have to respond to.

The real problem that I think we’re facing, the crisis that we’re facing is twofold. One is the corrosion by the far-right in America, of all of those premises and basis by which Democrat democracies work primarily, the one that is so fundamental that we don’t even think about it very often, and that is the normal oscillation of power.

That’s one of the things that democracies depend on is the idea that the Jeffersonians will be in power at one point and the Hamiltonians at another point and they will never like each other and they will each believe that the other is doing the worst possible things for the country, but we accept the idea that there will be a normal revolution in the revolving door sense. Not in the pikes and guillotine sense. That there’ll be a normal oscillation and revolution of parties in power, and that though we’re always unhappy when the wrong people are in power and they’re making guns more available and incarceration more frequent.

Nonetheless, we recognize that that’s a natural and inevitable part of democratic measures and democratic momentum. That of course, we’re living through a time when that fundamental idea has been corroded, in some respects destroyed in ways that we are almost incapable of dealing with because it comes from so far outside our experience.

As I have said at times, we’re living in a moment when it’s as though somebody brought a machine gun to a Monopoly game, right? Nowhere on the box the rules of Monopoly does it say you cannot purchase Park Place by pointing a machine gun at the other players, with threatening their existence, not because it’s acceptable, but because it never occurred to anybody that that would be the way someone would proceed. Nobody ever imagined bringing a machine gun to a Monopoly game. The analogy I hope is clear to all of you. Nobody imagined in the past that someone could simply a sitting president, could simply ignore the results of a free and fair election and attempt overtly and covertly to undermine it and remain and persist in power.

That’s not only something that’s never happened in the United States, it’s something that’s never happened in any of the mature democracies or immature ones of Western Europe, Canada, Australia, France, Great Britain. That in itself is a crisis and it’s an almost impossible crisis to resolve because our natural instincts as liberals in the small l sense as people who are committed to liberal democracy, no matter what partisan side we come at, our natural instinct is to rely on law to try and do the work of entrapping a lawless leader.

One of the frightening things you see, if you study the assent of Hitler in 1932, is that the people who you would rely on and who held in a majority of the vote, the Social Democrats on the left, the centrist Catholics on the right, not only were never able to make common cause against a demagogic would-be dictator, but that they relied unduly on their own constitution on the notion that if they simply proceeded as institutionalists and proceduralists, somehow that would magically entrap a fascist.

And one of the tragedies we have learned historically, and we are relearning again, is that in a conflict between proceduralists, institutionalists and fascists, the fascists always win. Proceduralists and the institutionalists are committed to procedures and institutions. The other side is not at all and do not care or mind what is lost by the destruction of those institutions. That, I think, is the particular and the grave crisis that we’re facing. That’s one side of it.

The other side of it, just as grave, and it’s one that I feel when I go to talk at liberal arts colleges and try and talk as often as I can to people the same age as my kids, both of whom are in their 20s, is that we are largely still unaware or insensitive to how fragile the freedoms and the responsibilities and the architecture of a liberal democracy is.

It is the air we breathe, it is the water that we swim in, and as a consequence, we’re largely unconscious of how easily it can be destroyed, how fragile that architecture is, how quickly Central Park can be overrun, how rapidly we can lose those rights and freedoms, even though we recognize that all around the world it’s happening every day.

I was just reading recently a piece about the closure, one by one, of every independent bookstore in Hong Kong by the Chinese Communist Party and the coffee houses of Tehran, which are the places where as you’ll read, where women feel free to come, take off their veils, engage in conversation with other women, not on political grounds necessarily, not about politics, but simply as one human being to another.

Those coffee houses are the prime target of the theological police. Exactly because they recognize that the commonplace civilization that they embody is the ground of the dream of an egalitarian and democratic and secular society. We tend not to be able to grasp that readily. We tend not to believe or to believe only too late that those institutions, that commonplace civilization, that air that we breathe, that water that we swim in can be drained and destroyed, poisoned and finished in remarkably short time. We have to turn to history, the history of recent times, but more broadly the history of modernity itself to recognize how fragile all of those things are, how quickly they’re lost, and how impossible it is to reconstitute them once they’re gone.

Having said all of that, the question always is that comes around to me then is having said that our engagement with liberal democracy isn’t casual, it isn’t in a certain sense political.

In other words, one of the mistakes I think we make as liberals in the small l sense is to think that the right cure is to find the one right program, the social democratic program that we might all desire. God knows I do. I’ve been writing about national health insurance for the New Yorker since 1986 actually, but that isn’t the point. It isn’t the politics themselves. It’s as I said, the superintending architecture that makes political argument possible that allows the oscillation of power, the ability to continue to talk back to the boss man, which are the distinctive features of a liberal democratic culture. Those are the things that are endangered, not politics as such, but the possibility of a political sphere.

What are we to do? Well, it seems to me that if there’s hope to be found in the description that I’ve given you is that despite its corrosion, despite its undermining by bad people and bad ideas, one of the truths about liberal democracies is that exactly because they do rest on social capital, on civic institutions, on commonplace civilization, that we are all in touch with those every day. We are capable of reinforcing, reconstituting, rebuilding the things immediately near at hand in our daily life and in our daily pursuits.

If we focus on that, it seems to me that we can then actually have a clearer notion of how we dissipate the clouds of fear that settle on us and make us seem incapable of action. One of my favorite stories is about the great Sufi mystic Nasreddin. Sure some of the stories of Nasreddin, and at one point Nasreddin is sort of a divine fool in Sufi legend, is standing on one side of a river, and on the other side a man calls out to him, “How do I get to the other side?” And Nasreddin thinks for a moment and then calls out, “You are on the other side.” I think that’s a profound political parable for our time. The other side that we dream of getting to is the side that we are already on, the duties and responsibilities we have in rebuilding the premises and platforms of democracy are immediately at our fingertips. The other side is already the side we are on if we choose to recognize it. Thank you so much for listening. Thank you. Thank you.

Remember Milton Berle, you’re a too young to remember. He would go like this and then this. I’d be delighted to take your questions. I know I’ve thrown an enormous amount out at you and there’s a microphone here from which to speak, so let me try and clarify all of that which is clouded and extend this beyond where we’ve been so far.

Audience 1: I’m not sure you’re going to be able to answer. Were you living in New York in 2016?

Adam Gopnik: Yes. Oh, my God, yes.

Audience 1: So I have spent many years trying to figure out how the New York Times allowed Donald Trump to get the nomination. That’s a home story they knew who he was.

Adam Gopnik: Now I’m going to guarantee myself a lifetime of bad reviews if the publishing industry continues by critiquing the New York Times. One of the striking features of Timothy Ryback’s book on the ascent of Hitler is the role of the New York Times. The New York Times had a correspondent named Birchall in Berlin and Birchall routinely and regularly would explain to the readers of the Times not to get panicked about Hitler, not to take him too seriously, that it was all performative, and that the anti-Semitism was a sop to his base and that the real people to watch and understand were the respectable conservative politicians behind him. Birchall wrote this over and over again, could not confront or look at the reality of what he was facing. Now, let me say on behalf of Birchall, on behalf of the Times in that way, having been immersed in that particular kind of journalistic culture, it’s not what I participate in, but of course, it’s one that I see and many people I know and respect are part of.

It isn’t that and it’s not just the Times, the Post, the media are surreptitiously or clandestinely in favor of Trump any more than Birchall was in favor of Hitler. It’s that they feel that the value added that they bring to the conversation is to deny the obvious, right? And to give you special information that you otherwise wouldn’t have. The headline “Deranged Demagogue Tries to End Democracy,” which is the actual headline that should be on every newspaper, on every mind, blazoned on our consciousness every time they feel that gets exhausted after you’ve said it once or twice.

So you need something new, you need a new take, new information, and so on. So I won’t forgive them, but I can understand how it happens. But you’re absolutely right, and one of the lessons that I wanted to draw from the experiences of not just 1932, but of Argentina and Italy and all the other places, Hungary most recently, where democracy has ended or been effectively ended, is that inevitably there’s a kind of paralysis on the part of the press, right? Don’t want to face the truth of what we’re looking at. And I think that’s true.

Audience 1: It was kind of worse than that though. When you remember CBS, Moonves says, “Donald Trump may be for the country, but he’s great for us.”

Adam Gopnik: Yes. This is sadly true. This is sadly true as well. Gentleman here.

Audience 2: Hi. I wanted to ask you about the role of technology in the superintending architecture you talked about because it seems to me it’s not just a modification, it’s a rip and replace. We’ve gone from knowing how to live on land to now we’re underwater and everyone’s trying to figure out how to breathe. If we were here two years ago, we wouldn’t be here. This commonplace would be on Zoom, and that would be for a short time a blessing and then a long curse.

Adam Gopnik: Terrific question, and of course one that I’ve rooted on is everyone has, I did a long piece for the New Yorker called “The Information” in 2011, which was my attempt to grapple with all of the issues of how has the new technology, digital technology of all kinds, how has it changed our consciousness? Because there’s no question that it is the crucial new thing you could … If you look at the popular culture of the 1980s or 1990s, The Sopranos or Breaking Bad, things that in some respects preceded that revolution. They’re totally like the same things that we’re seeing now. There’s very little difference between those things, and yet the way they’re disseminated is utterly unlike.

I tend to be a bit of a steady-state thinker about those things because I think it’s very easy for us to forget or look past the ways in which … There was an equally strong insistence, say in the network television era, that television had completely fragmented our minds, made us lose our attention span, had eliminated the possibility of sustained discourse, and replaced it with tiny images. Now of course… Or sequences of images.

Now, of course, we look back at the era of three networks as this paradise of non-polarized open debate. And if you’re a Canadian as I am in origin, you look back fondly on the time when there were two television networks in Canada, both in black-and-white, and yet it was watching those two that led Marshall McLuhan to believe that modern consciousness had fragmented beyond repair. So in a certain sense, I believe that’s a story we want to tell ourselves as much as a story that is implanted in us. I don’t mean to underestimate the force of new media in altering our views. We all have had that experience when we go into our teenager’s room if you have teenagers and you say to them, “Would you please get off your phone and come and watch television with the rest of the family?”

Because television is now the common, the hearth that we place where things go on. So I’m guarded in my feeling of how much technology itself can corrode our understanding, but there’s no question that that polarization is powerful, and that is something that we’re aware of. That’s a non-answer answer, but it’s at least an attempt to dive into it. Yes, gentleman here.

Audience 3: Hi. Thank you so much for this talk. It’s been great. I’ll hate myself if I don’t ask this. Some of the audience may hate me because I am asking this, but I’m curious about what music you’re listening to at the moment, and I appreciated that you talked about this common space. And a more poignant question is, do you have any thoughts about Beyonce’s Cowboy Carter album and its impact on culture in the country right now?

Adam Gopnik: I have, yes, in a word. So what music … I’m a music nut. I live for music. I would much rather have been a musician than been a writer. I would much rather have written Oklahoma than Hamlet. The record shows I wrote neither. So I know I’m … Not Oklahoma. Guys and Dolls. I would rather have written Guys and Dolls than all of my books.

I listen, I write, but actually, I have a nights and weekends job now writing songs and musical theater. You can find a show of mine, Our Table on Spotify with the original cast recording. And so I listen to a lot of theater music is the simple answer. I’m intrigued by the complexities and demands of theater music. So I listened to the contemporaries, Andrew Lippa, Jeanine Tesori, Tom Kitt, and of course, like all of us, I go on listening to Stephen Sondheim’s extraordinary work, which changed my life when I heard it for the first time in 1977.

So that’s my musical preoccupation. And of course, like every teenager, it astonishes me that the music that was popular when I was 16 and 17 is still the greatest music ever made, and I don’t understand how anyone can dispute that.

So in 1970, the greatest music was obviously made in 1971 by Joni Mitchell and the Stones and so on. And I listened to that music all the time. What fascinates me about Beyonce is “Blackbird,” her recording of the great Beatles song “Blackbird,” because she gives it a political touch, a political slant, both by virtue of being a Black woman singing it, but also in the harmonic way it’s done. And I had always thought Paul McCartney says about that song that he wrote it as a song about Black women in the civil rights movement. And I thought that sounds like one of those things you would say afterwards to sort of give, which we all do, right? Say, “Oh yes, that was my civil rights song.”

But someone directed me just the other day, and you can find it on YouTube to a recording of Donovan if anyone remembers Donovan [inaudible] … I do and love Donovan. That’s a whole other subject, [inaudible] … and Paul McCartney talking about this song, and Goddamn it, Paul McCartney says, “I was thinking about the civil rights movement when I wrote this one here. You want listen this.” In that kind of McCartney mutter. So apparently it’s true.

So in that sense, thinking about, and I’ll add one more thought to this chain of thoughts, it is astounding and astonishing that music that was made 60 years ago continues to have that kind of hold on our imagination and our attention. It’s an extraordinary thing. I’m a Beatle fan, but for life, but it’s a reminder of the power of great art in plain English, that it genuinely not just figuratively of the humanities, not just as a figure of speech, but as an actual thing, can continue to speak in new ways to new generations. Thank you for that question. Lady here. Oh, OK. Oh, here. Yes, please. Yeah.

Audience 4: Great. I’ve been an admirer of you for a long time, so thank you for coming. I’m a political scientist and I just feel like the world is so polarized now that we don’t have these … The zoo is still not polarized, so that’s good. But there are fewer and fewer places that are like the zoo and universities being one of them, that now Republicans are less supportive of higher education. So how can we apply what you say to this new polarized world?

Adam Gopnik: Well, again, it’s the big question, right? I’m inclined to think that, to some degree, we overstate the degree, the novelty of the polarization of our politics, and so on. I’m old enough, just old enough, I was a kid then, but an attentive kid to remember, 1968, 1969, the Vietnam the movement.

The Vietnam fights many of which took place right here on this campus, which were perceived at the time to be equally divisive, to be equally polarized, and to tear the society apart. That moment had a cultural revolution attached to it as well of exactly the kind we were talking about a moment ago. So we look back on it more fondly than we look on this somewhat more dire moment. The point I’d make, and it was the point I was trying to make, so I’m glad to have a chance to reiterate it, is that the problem for a liberal democracy is not polarization.

To some degree, liberal democracies will always be polarized, and sometimes, as in the time of the Civil War, they become so polarized that they become wildly violent. That’s part, as you know, better than as a political scientist, that that’s part of the larger pattern.

So the question is not so much how do you keep the society from being polarized, but how do you get people to buy in, to accept the idea that within that polarization there will be an oscillation of parties in power and that it will be, however, grudgingly nonetheless, will be accepted by all sides. If you think about it at all in the great span of human history, that’s an astounding thing, right? That isn’t the way human beings normally change governments. That isn’t the way human beings normally change leaders to say, “Oh, you now? All right.” That’s not the way we do it.

And so having that as whatever you want to call it, a practice, a tradition, a premise is I think the thing that’s most endangered and the thing most in need of protection. The so to speak, other side, as I’ve said, the issue I’ve written about most passionately, most often along with mass incarceration is gun sanity and gun control. And if I had the power to do it, if I were king tomorrow morning, I would have America move to a gun regime like that of every other democratic country, Canada or Great Britain. I don’t have that power and I could never get that power. It’s not in the nature of the particular democracy we live in. Liz Cheney, who I see as a wonderful partner in this, speaks for Wyoming, and she speaks for a culture which finds in guns powerful symbols of autonomy and liberty.

That may be an alien conception to you and me, but it’s a conception we have to live with because it’s one that our fellow citizens hold. And that in some sense, it’s still tolerable to us. Nonetheless, we have to build coalitions on the vital issues with the Liz Cheneys of the world and do it with delight. One of my great heroes I had a chance to write at length about just recently is Bayard Rustin, the great architect of the civil rights movement as a movement of the March on Washington and so on.

And the one thing that Rustin, who I’ve been writing about now for 20 years and now has been rediscovered and made into a movie star and so on, but the one thing that Rustin believed in with an almost religious fervor rooted in his religious fervor for Quakerism, for the Society of Friends in which he’d been raised, the one that he believed in was the power of coalition.

And for him, that was the first plank in any party. That was the first move in any social movement, was to build as broad and as strong a coalition as you could. And coalition building that’s what I was trying to say about Nasreddin, and you are on the other side. Coalition building is possible to us at any moment, and it’s the only antidote, however inadequate to polarization. Gentleman in the back here. Last row. We’ll go one to you and then.

Audience 5: OK. OK, thanks. You alluded to that the corrosion was not entirely on the other side. It was not all on the other side. And so I was hoping maybe you could speak to what you view as the corrosion that our side has contributed to.

Adam Gopnik: Well, but it’s assuming everybody in this room is on the same side, but that’s what Nasreddin said …

Audience 5: You know what I mean?

Adam Gopnik: Yes. So on the … Look, we have to think about coalition building with people who are not of our class and kind and caste. It’s always the case that I call them what we will, liberal forces, progressive forces, radical forces become infatuated with their own rhetoric and have a bad habit of living with people who agree with them and then don’t have the habit of being in the world where people disagree with them and they have a hard time accepting. We do. We have a hard time accepting that.

So one of the jobs we have to do is to be able to distinguish, this is what I’ve been trying to say this afternoon. We have to be able to distinguish between views radically unlike our own that we would like to argue against, that we would like to vote down when we have the chance, but that are nonetheless part of the necessities of democratic debate and views that end democratic debate. So we have to be resolute in making that distinction so we don’t make the companion error. That’s one thing that I think people on our side have to do.

The other thing which I talked about is we can’t rely on institutions and procedures to do the work that only individual agency can do and I do not hesitate. I don’t want to cloak my feelings. I think that we’ve seen the tragedy of Merrick Garland in exactly those terms, someone of impeccable instincts, but who believes if I only reassert the role of the Department of Justice doing its work, then everything else will resolve. That I think, and that’s why I referenced the Social Democrats in Germany in the 1930s, that I think is a delusion that to which our side in that sense is subject. Gentlemen behind.

Audience 6: Kind of a similar question, but how do you account for abolitionism where someone who would read the rhinoceros scene that any sort of harmonious encounter between Taylor and Mill of between freedom from and freedom to requires the caging of this animal that could destroy us?

Adam Gopnik: Thank you for mentioning that because I was on my beat sheet and I forgot to land it because the other day I was at Wesleyan, I was giving another version of this same talk, and someone reminded me of that, that you’re looking past the rhinoceros who’s been caged and shouldn’t be in a cage at all. It’s a good point.

What I think that indicates is that we all come to … We’re all part blind. We come to the limits of our circles of compassion with surprising celerity. So you have Mill and Taylor, and there could not have been two more far-seeing enlightened, and ambitious people, people ambitious for not just for individual liberty, but for what we now call social justice. And they couldn’t see that issue. That’s why I always say that the difference between … The thing that makes liberalism unique is that it’s a program for perpetual reform and conservatism is not a program for perpetual reform.

And people get exhausted by the search for perpetual reform. Someone said once the hardened reformer can never make up her mind, which is the most beautiful word in the language, compulsory or forbidden. That’s a classic reproach of those of us who are committed reformers. But we have to be committed to reform exactly because our circles of compassion, no matter how we try to broaden them, come to an end.

I will give you an odd instance of this, but it’s in a play, a musical play I’m writing right now, which is about the meetings of the American Psychological Association in 1973 when homosexuality was taken out of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual and treated as a normal thing. And Andrew Lippa and I are writing a musical about this because we’re fascinated by the true life story of the father, who was the president of the association, violently opposed to the resolution and his 18-year-old son who was gay and had to come out at that point.

And in describing the father, what I’ve been struggling to do, and this may be true to the history or not, but is to describe someone who sees himself as a liberal-minded, as a compassionate, and as an engaged man, but has banged his shins on the edges of his circles of compassion. Not meant to be a retrospective lecture to a bad man, but a perpetual reminder that we are all in that circumstance and it’s a perpetual effort to refocus our attention on the other, to re-understand, to broaden those circles of compassion. So I’m writing a play about that right now, and it’s an endlessly demanding task, but it’s what makes liberalism distinct is a perpetual commitment to reform. Gentleman back here.

Audience 7: So when you were talking about the rise of fascism and how there’s … or even totalitarianism or governments that are usually non-democratic, there’s usually a pattern. There’s a major pattern in … There’s an instance in the which the other side, the majority takes away something from the minority.

In this case, we’re going to say the minority is the right flank and the majority is going to be the left flank. And with that leads to the rise of more radical leaders, or for example, cults or even godly figures, for example, the rise of Stalin or even the rise of Putin, the rise of Hitler. They have more grasp because the other side desires something and it’s usually caused by the majority.

Now, we can’t automatically take blame … We can’t automatically put the blame always on the other side. There’s always something that we could do to avoid this. What is that thing we could have done to avoid something like this from happening again?

Adam Gopnik: It’s a great question. One of the things that’s striking, if you study the election of 1932, the elections, there were several, 1932 in Germany. And again, I don’t want to draw overly tight parallels between that moment and this moment. And yet there’s a similar pathology, identifiable pathology, that as Snyder and Benghiet have pointed out we can observe just the way, we can observe the growth of a cancer.

And one of the things that’s striking is that people tend to react to abnormal circumstances as though they were normal. So the people who are voting in those elections, when political scientists look at what motivated them and moved them, who voted for who, they were voting in completely normal patterns. Nobody was saying in Germany at that point, “What we need is an apocalyptic nihilistic cult that will leave hundreds of millions of people dead and Germany utterly destroyed.”

That was not what they were voting for. They were voting for their familiar allegiances and they were voting against their traditional enemies even more than anything else. And if there’s one thing that seems to distinguish the fall of democracies and the rise of authoritarian cults, it’s the capacity of people to convince themselves that the other side is so depraved and deranged that, and this is always the language, “We have no choice.” “I have no choice.”

You may have seen Bill Barr saying that the other day. This is somebody who knows firsthand and has said categorically that Donald Trump is unfit for office — a serial liar who cares only about himself. But he came out and said he’s going to vote for him because the other side is so horrific. Now, that seems to me delusional because the other side is composed for good or ill, not of radicals, but of centrists.

But that’s the psychology by which this precedes. And you have to be constantly trying to intervene in that psychology and say, “No, that is not true. The other side is not composed of demons, it’s composed of those people.”

And in the same, we have to do the same work and recognize that the majority of people who support authoritarian causes are not consciously authoritarian. They’re simply voting their fears in more than any other thing, and that’s part of the duty of … Good Democratic politicians are able to calm and placate people’s fears and replace them with hopes.

That’s what a good politician can do. And we should never … One last thought, never minimize the role of a good politician. We tend to have contempt for politicians because, in the nature of their work, they have to compromise all the time. That’s the nature of doing it. To be able to do that effectively in the same way that enables them to reduce the level of fear being felt by at least a part of the, so to speak, other side. That’s a very powerful way of supporting and defending social institutions, liberal institutions. We have time for one more?

Stephen Best: Sure.

Adam Gopnik: Lady here.

Audience 8: Yes. Challenging the back and forth, the natural oscillation that you described between say, in this country, Democrats and Republicans. What I see challenging it are such things like the Federalist Society and the Heritage Foundation that have helped create the Supreme Court that we have. And I’m wondering how you think we could counter those kinds of insidious forces.

Adam Gopnik: Yes, absolutely. One of the things I always expect, somebody always raises when I’m trying to talk about these subjects is say, what a horribly naive vision you’ve given us because you’ve totally left out the role of money and of big money in shaping it. And the response I would have, and also to the existence of those societies, which depend on dark money and big money to persist at all, is that at any moment in history, those values, the values of liberal democracy are going to be under threat. There has never been a moment when we can look and say, “We’re sailing this ship smoothly along and we’ll all come.” I’m old enough myself. I’m not that old. I’m old enough to remember though, that in the 1950s everyone said that liberal democracy was doomed in the face of the militant force of world communism.

People forget now that Ronald Reagan didn’t come to power praising the city on the hill, and its inexhaustible power. It came just the opposite, saying, “We’re threatened, we’re on our way out,” and so on. That was the rhetorical force of his arguments. And then I’m old enough to remember, I was on the site in 9/11 and everyone said, “Oh, how can decadent liberal cities ever compete against the militant Islamic forces?” Again and again and again we hear that. And if we go back to before I was born to the 1930s, that’s all anyone said. Liberal democracy was obviously defeated.

It was the why the New York Times wrote as it did, and yet at every moment, it’s turned out to be resilient, more resilient than we know. Able not to easily master, but to counterpoise the forces of, including the forces of big and dark money, and this might be a good place to end. I think the mistake we sometimes make is that we see the values of liberalism in the sense that I’m trying to articulate them today. We see them as a kind of a date with destiny. History tells us that they’re the best solution to the problems of modernity or the problems of the Industrial Revolution or all kinds of things.

I’m inclined to think that there are simply permanent values that you can find going back to antiquity. You can find all over the world values that we sometimes call the values of humanism. Values of pluralism above all. The value of believing that social coexistence is better than social violence. Tendency to believe that ideological disputes should be settled as nonviolently as is humanly possible, that religious wars are bad, and above all, I think the belief that fanaticism is the enemy of the human spirit and humanism is simply the perpetual antidote to the fanatic turn of the human mind.

All of those things seem to me not to be parts of an ideology developed to suit a historical moment, but parts of a system of beliefs that will be perpetual and that we will whisper to each other in the dark even if they’re eclipsed for a time. Thank you so much.

[Applause]

[Music: “Silver Lanyard” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Outro: You’ve been listening to Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. Follow us wherever you listen to your podcasts. You can find all of our podcast episodes, with transcripts and photos, on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

[Music fades out]