Hard knocks for Nox, UC Berkeley’s youngest peregrine falcon

But thanks to UC Davis veterinarians and other helpers, his broken wing is mending.

July 25, 2024

His three siblings will soon fly away, leaving UC Berkeley to start new lives. But Nox, the youngest peregrine falcon to hatch on the Campanile this spring, won’t be doing the same just yet. Far from home, he’s healing from a broken wing.

“The good news is he’s a real champ,” said Dr. Michelle Hawkins, director of the California Raptor Center at UC Davis, where Nox had surgery earlier this month. His weight is back to what it was pre-surgery, she said in a livestreamed Q&A on Wednesday with Cal Falcons, and although he’s lost some muscle mass in the past few weeks, “we’re really pleased with where he is right now.”

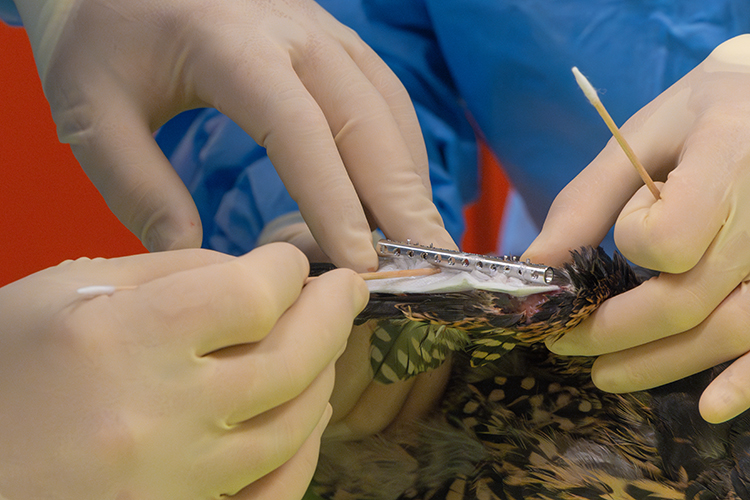

Courtesy of California Raptor Center, UC Davis

On July 3, Nox was found in distress at the Berkeley Marina. He was retrieved from the water by Bay Raptor Rescue, transported to WildCare in San Rafael and taken on July 5 to UC Davis Veterinary Hospital.

It’s unknown how Nox got hurt. This stage of a young raptor’s life “is a very hard time in the wild. The average mortality rate is about 50% in the first year of life for a wild bird,” said Sean Peterson, a Cal Falcons environmental biologist.

As a juvenile no longer able to continue learning skills, such as hunting, from his parents, Annie and Archie, it’s hoped that Nox — after many weeks of healing— can resume training for adulthood, this time with a falconer at Davis.

Currently, Nox is in the raptor center’s quarantine building, in his own room and in a soft-sided kennel, with a bandaged wing. His medication is being added to his food, said Hawkins, who also is a professor in the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, “so he isn’t handled [by humans] more than he has to be.” Recovery could take eight to 10 weeks.

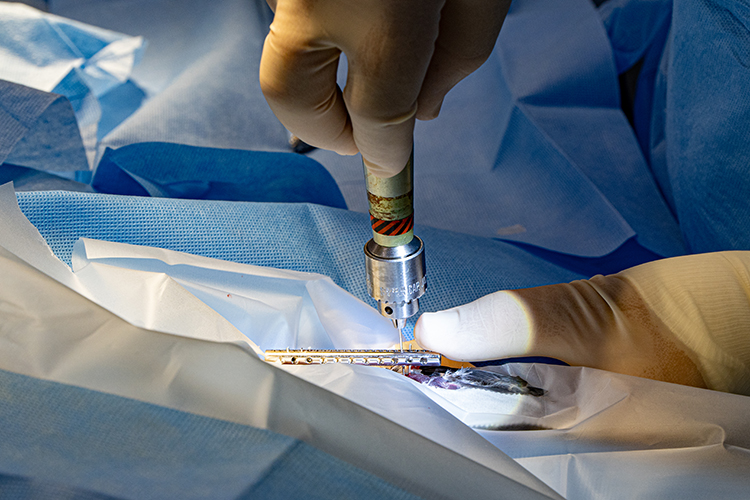

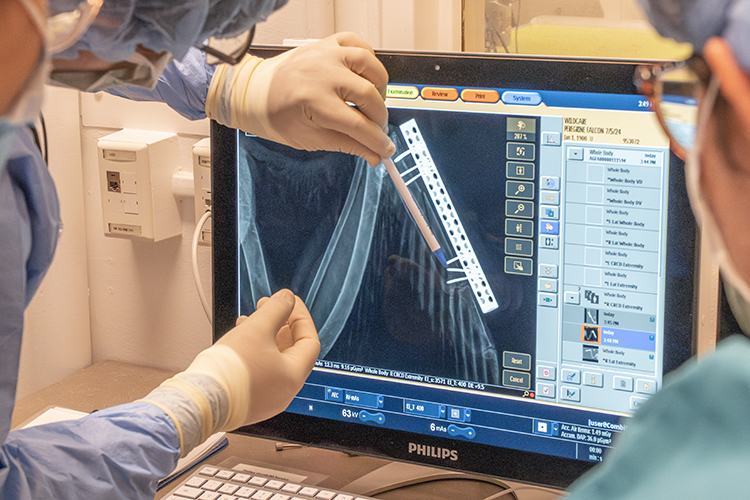

Mike Bannasch/UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

After that, “all raptor patients need to get into athletic condition,” she said. “Most species, like owls and red-tailed hawks, are put in an aviary and allowed to fly. But falcons are not safe there because of their speed. So they work with falconers … ” to move beyond their injuries and build muscle mass, fly again in the open sky and hunt.

“It’s really for his survival to get those skills and to be supervised,” said Peterson.

Hawkins said the center, which takes in 100 to 200 sick, injured and orphaned raptors each year and successfully returns about 60% of them to the wild, intends to eventually return Nox to the territory he came from.

“Berkeley is in an urban area,” she added, “so we have to make sure he’s safe with initial flights, and then Nox can decide where he wants to be.”

Peterson said Cal Falcons is grateful for the number of people who “have come together to take care of this tiny, fierce bird. It’s astounding and a testament to the empathy and care that people have for wildlife and the animals that share the world with them.”