At 16, he was a cricket star. Then an accident made him rethink his future.

New UC Berkeley student Vihaan Hampihallikar started playing cricket in Singapore at age 6. Ten years later, he made the national men’s team. After a traumatic eye injury derailed his plans, he started a project to help others get the health care they needed.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

August 26, 2024

Vihaan Hampihallikar had a cricket tournament to train for. But unlike his other matches, the stakes were higher this time. It was December 2022, and he’d recently made the Singapore men’s national cricket team as his country’s youngest player, at just 16 years old. He wanted to prove himself to his more experienced teammates, most of them in their 20s and 30s.

Vihaan wasn’t worried; he’d been training nonstop for this moment for years. Plus, he liked the pressure. He was used to it. It often gave him an extra push to achieve at a high level.

“I’ve always thrived in competition,” said Vihaan, who’s joining UC Berkeley as a first-year student this fall. “It feels natural to me.”

After his first tournament on his new team, Vihaan realized he needed extra training. He wanted to do really well in the next tournament in Dubai in February. So he set up a couple sessions with a longtime coach in Mumbai who was well-versed in advanced throwing, or bowling, techniques.

Little did he know that his carefully laid plans to be a world-class cricket player were about to be derailed — and he’d be forced to rethink his future.

Courtesy of Vihaan Hampihallikar

More than a sport

Born in Mumbai in 2006, Vihaan moved with his family to Singapore at 4 months old. The island city-state in Southeast Asia, known for its high standard of living and top-notch education system, offered an environment where his parents felt their son could reach his potential.

“My mom really wanted me to focus on academics, and it was my dad’s dream for me to play sport,” he said. “But when you know you have to do well in both, your body just gives you the extra drive that you need.”

Since he was young, Vihaan has known that cricket holds a special power in Indian culture. He remembers watching the 2011 Cricket World Cup on TV as a 4-year-old with his family. When India won, the second time since 1983, Vihaan looked on as his parents screamed in jubilation.

“It’s something that flows in the veins in every person,” he said. “It’s not just a sport; it’s an emotion. It’s brilliant.”

Growing up, when he wasn’t in school or studying, Vihaan was playing cricket. At 10, his dad enrolled him in a training academy, and by 13, he was recruited to play on the national Under-19 team. So when he made the men’s national team three years later in 2022, it felt unreal, like a dream come true.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

The sound came first

On the morning of Dec. 26, 2022, Vihaan met up with his coach at Gandhi Maidan Stadium in Bihar, India. They began working on one of the most difficult bowling styles called a leg spin, where the ball — smaller and heavier than a baseball — spins from right to left when it bounces off the pitch, away from the leg side of a right-handed batter. Yes, it’s as hard to master as it sounds.

Cricket is the second most popular spectator sport in the world behind football, which Americans call soccer. While cricket is popular in Asia, Australia and the U.K., it’s not commonly played in the U.S.

As Vihaan and his coach were working on his leg spin, his parents stood on the sidelines watching the session, chatting and snacking in the sun. Several other cricket practices and matches also were happening in different areas of the massive field.

About 10 minutes in, Vihaan delivered a ball and was listening to his coach’s feedback. He still remembers the sound that came next.

“It’s hard to explain it,” he said, “but I could hear the revolutions of a ball.”

From tragedy came determination

As a reflex, Vihaan turned his head toward the sound, and a cricket ball — which can travel between 40 and 100 miles per hour — struck his eyeglasses. His hands flew up and cupped his right eye, and he doubled over on the ground. As a cricketer, Vihaan was used to shaking off injuries. But he couldn’t shake this one.

His mom knew immediately that something was wrong. She quickly strode across the field and gently asked, “Can you open your eyes?”

He slowly moved his hands away and opened them.

“There was blood everywhere,” he said.

Within minutes, he and his parents boarded a rickshaw and sped to the nearest hospital, where a doctor assessed the damage. The next morning, he was transferred to another hospital for a two-hour surgery.

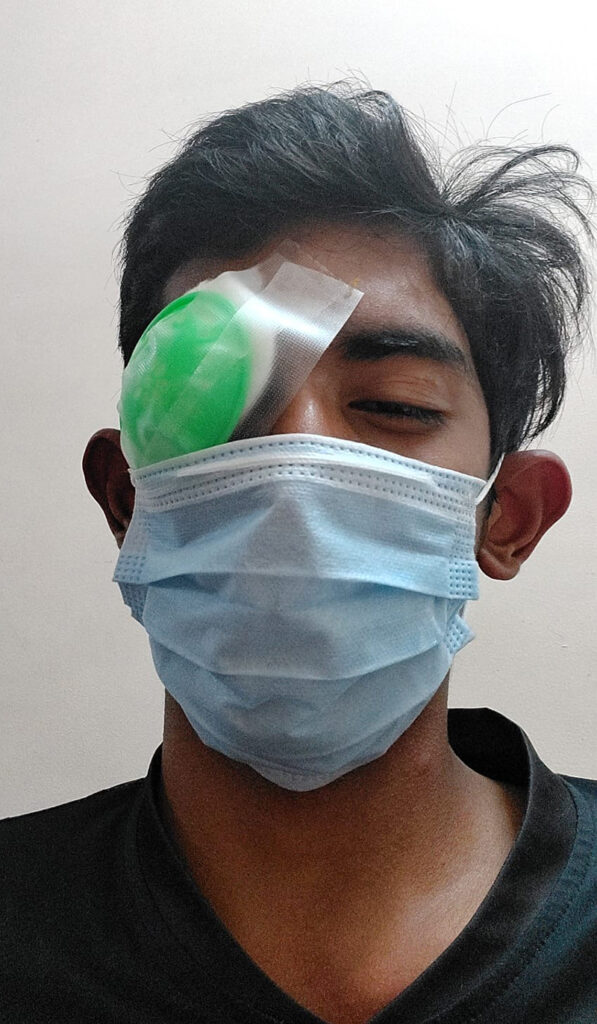

Courtesy of Vihaan Hampihallikar

After the procedure, the first of five to come, the doctor delivered the bad news: His shattered eyeglasses had pierced and destroyed his right eye’s lens and his cornea, the outermost layer of the eye that needs to be clear for good vision.

Lying in a hospital bed with a bandage covering 40 stitches in his eye, Vihaan only worried about one thing: Could he play in the February tournament?

“Absolutely not,” said the doctor.

“That’s when I completely lost it,” he said. “I’m not one who shows emotion easily, and I was bawling. I was wailing, ‘Why? Why did this have to happen to me?’”

“Will I ever play cricket again?” he wondered. “Will I be blind in my right eye forever?” Nobody knew for sure.

The months to come would be full of challenges, but they taught Vihaan that he had the strength to deal with whatever came next. His struggle also led him to a resolution: He would use his accident to help others who required eye surgeries but couldn’t access the care they needed.

Channeling his passion into helping others

Vihaan underwent surgery after surgery over the next seven months, to repair his cornea and eventually replace his eye’s lens with a synthetic one. At times, it was excruciating, both the painful procedures themselves and the heartbreaking uncertainty of his future in cricket.

All the same, he knew he was lucky.

“So many worse things could have happened,” he said. “What if the glass pierced both my eyes, and I went completely blind? What if I couldn’t see the right doctor at the right time? What if my parents didn’t have connections with the best specialists?”

Every time he went to an eye clinic in India, he passed by hordes of people waiting outside, hoping to be seen by a cornea specialist. There simply weren’t enough doctors trained in the field, nor were there enough corneas available for those who needed a replacement.

Never one to balk at a challenge, Vihaan, then 17, decided to help.

He teamed up with the Singapore Red Cross and started Open Your Eyes, a project that urges Singaporean residents to pledge to donate their corneas after they die for essential surgeries. He asked his family and friends to support the cause. He gave talks in schools and universities across Singapore. And slowly, word about the effort started to spread.

“Everyone has a different ideology about donating your body to science,” he said. “Some people are comfortable with it. Others aren’t and have their minds set. But I try my best to convince them.”

So far, Vihaan said, more than 100 people have pledged to donate their corneas through Open Your Eyes. In 2024, Vihaan’s project was nationally recognized by the Red Cross.

Courtesy of Vihaan Hampihallikar

He continued to push himself, pursuing new projects to help others get the support they needed to live more fulfilled lives. In 11th grade, he led a 15-student engineering team to create the Qube, a learning aid designed to assist children with ADHD and autism using sensory methods. In 2023, the team won the Singapore Junior Achievement Company of the Year Competition and was a finalist in the Asia Pacific Junior Achievement Company of the Year competition that followed. That same year, he also helped launch and run Earthfirst, a nonprofit that employs visually impaired workers to sew shopping bags and other items and sells them worldwide.

The U.S. needs cricket, he says

At Berkeley, Vihaan plans to keep building his entrepreneurial skills.

“That’s my biggest love,” he said.

He’s joining the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, and looks forward to being a part of the campus’s collaborative learning atmosphere.

After earning his bachelor’s degree, Vihaan is open to pursuing many fields, but is especially interested in renewable energy, possibly developing highly efficient batteries to compete with fossil fuels, something that he said “needs to be eradicated right now.”

Courtesy of Vihaan Hampihallikar

“Climate change was introduced to us in the first grade,” he said. “The more we learned, the more we realized how, even by 2030, it could become irreversible. It’s surprising to me that more attention isn’t being paid to it in the U.S. presidential election, since it could eradicate humanity as we know it. It’s something that I’m very passionate about, as everybody should be.”

And just recently, he started playing cricket again — he has regained 60% of his vision in right eye. But his depth perception is still off, so he’s easing into it for now. He might have his cornea replaced someday, but at this stage of his young life, the risks of doing it outweigh the potential benefits.

He plans to join Berkeley’s cricket club and hopes to build up its membership while on campus. He’d love for cricket to be more popular across the U.S.

“I think cricket is a sport that needs to be spread in the country,” he said. “I’m not sure if I can single handedly do it, but I’ll try. Let’s see what happens.”

After all, cricket isn’t just the best sport in the world, he said. It’s a way of life. One that he’ll always choose, one way or another.