Sociologist examines Appalachian voters’ rightward shift, with Trump as their ‘shame shield’

UC Berkeley sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild traveled to eastern Kentucky to study how pride and shame affect people's politics. Then came 'a perfect storm.'

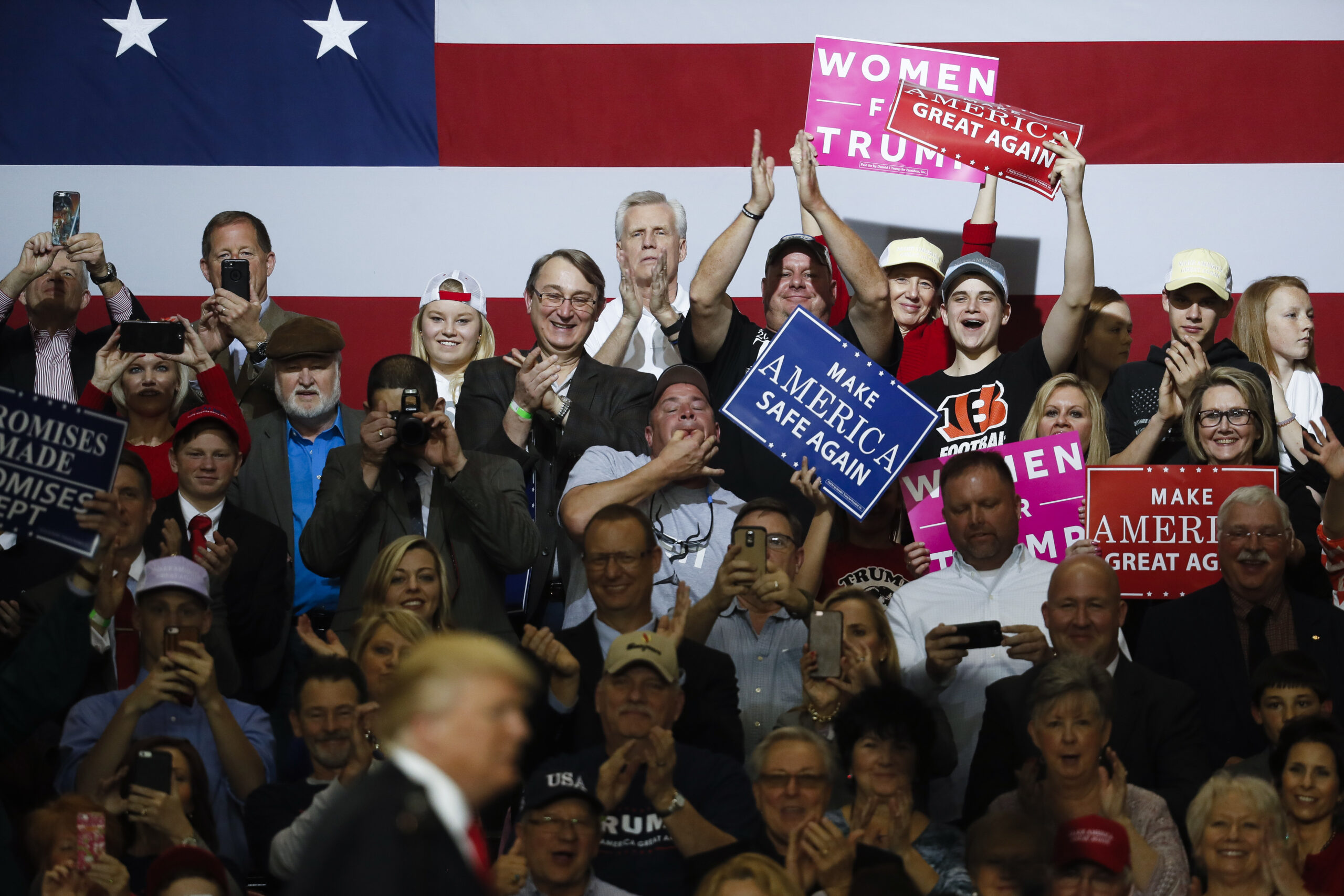

John Minchillo/AP

September 5, 2024

In her 2016 bestselling book Strangers in Their Own Land, UC Berkeley sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild proposed that everyone has a “deep story” — a narrative about one’s life and the world that’s based more on emotion than facts, a story that feels true.

For Tea Party conservatives who gave rise to Donald Trump nearly a decade ago, their shared deep story was focused on the American Dream. That dream was just over the hill, they told themselves. But the line approaching it was not moving. Then, refugees, women and people of color jumped ahead, and President Barack Obama’s policies encouraged them to cut in line. Meanwhile, white men without college degrees stood still and grew more resentful by the day.

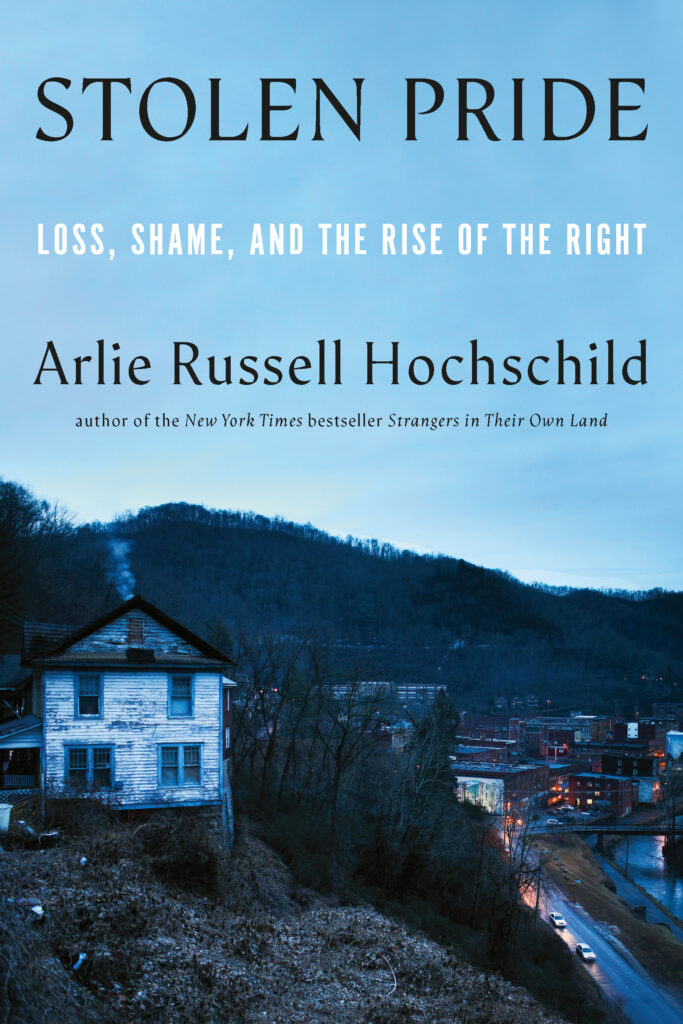

Courtesy of Mark Leong

Now, eight years later, Hochschild’s new book Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame and the Rise of the Right proposes that the deep story explaining Trump’s continued support needs a new chapter.

In it are two bullies, she writes, recounting a more recent conversation with a mayor in the heart of Appalachia. There’s the ominous bad bully — a group that includes the Democratic Party, the Justice Department, CNN — that pushes around the downtrodden and encourages line-cutting. And there’s a good bully — Trump — who arrives to battle against an expanding list of enemies.

“The ‘they’ has grown larger,” Hochschild told UC Berkeley News last week, and Trump has taken on and embraced being their “shame shield.”

This role plays out in a seemingly endless, four-step loop, said Hochschild. First, he says something provocative or outrageous. Politicians and the media who represent the bad bully shame him for saying it. Trump emerges as the victim who’s been hurt by their insults or censored. Then, Hochchild said, Trump “roars against the shamers.”

This anti-shame ritual wasn’t just a show that Trump’s followers watched, she writes.

“He continually invited his followers into it.”

Stolen Pride expands on Strangers

While it continues some themes from her 2016 book, which took place in Louisiana, Stolen Pride (out Sept. 10) spans a range of distinctly Trump-era events and Biden-era policies from 2017 until earlier this year.

When she began researching the book in 2017, Hochschild homed in on Kentucky’s 5th Congressional District, the whitest and second-poorest in the country. In the heart of once-booming coal country, 80% of voters there supported Democrat Bill Clinton’s presidential win in 1996. The region has since swung in the opposite direction — 80% of voters supported Trump for president in 2020.

The forces behind the political shift and the economic hardships fascinated Hochschild. Books written by Hochschild, a renowned Berkeley sociologist and former civil rights worker, have explored society’s largest changes and challenges, from the expansion of women in the workforce to the emotional labor of service work.

She’s become a go-to voice explaining the rise of the anti-government Tea Party and, more recently, the staying power of Trumpism.

She had some ideas based on her earlier work. White voters older than 25 without bachelor’s degrees account for 42% of Americans. Theirs has been a unique story of economic and social loss, Hochschild said. While Black people without bachelor’s degrees are poorer overall, they’ve seen some wage growth and economic improvements. White people, meanwhile, have been sliding down, especially in Appalachia, where coal mine jobs evaporated and the opioid crisis hit hardest.

“What’s going on in a region like this that would make pride and shame especially relevant?” Hochschild remembered wondering when she arrived in Pikeville, Kentucky, in 2017.

‘Perfect storm’

She’d barely begun exploring that question when she realized she’d walked into a confluence of disruptive events. Coal jobs had been leaving. An opioid crisis had been coming in.

And then in April 2017, Matthew Heimbach, a known white nationalist organizer who’d helped to lead a violent rally in Sacramento in 2016 was planning a march through the heart of Pikeville. Hochschild observed how tensions, already high after the 2016 election, were ratcheting up.

Where many saw the April 2017 march as another sign of surging right-wing extremism, she saw it as a confluence of events paired with social dynamics and the participants’ feeling of loss — of something having been stolen.

“I thought, ‘Oh, no. I’m looking at a perfect storm,” she said. So she interviewed all parties involved: the “perpetrators,” the protectors (town leaders), the potential victims (a Black civil servant, a Holocaust survivor, and an imam). She interviewed “faces in the crowd,” top to bottom and politically side to side.

That storm anchors the first half of the book and, as it turns out, was a prelude to the Charlottesville march later that year. Also interviewed repeatedly is Heimbach, a right-wing extremist who organized the rally at age 27. He and Hochschild talked about his German and Irish heritage, his adoration of Russian President Vladimir Putin, and how Star Wars partly inspired his extremist beliefs and his adamant refusal to accept shame.

Brian Bohannon via AP

Over the decade-plus that Hochschild, now 84, has spent researching anti-government and right-wing extremists, she has pondered the proverb, “If there is no wood, the fire goes out.”

“You have Donald Trump, who is the match,” she said. “But matches don’t catch on everywhere.”

You have Donald Trump, who is the match. But matches don’t catch on everywhere.

Arlie Russell Hochschild

While Hochschild interviewed people — primarily men — who celebrated their careers with pride and devout, up-by-your-bootstraps individualism, the inverse was also true. If the coal mine went out of business because of automation, offshoring or macroeconomic forces, her interviewees viewed their job losses as profoundly personal failings to be ashamed of.

Imbued with a more individualism-focused notion of pride, members of lower-income, less-educated communities are more likely to internalize job loss as a personal failing, she said. By contrast, more educated people had a more circumstance-focused notion of pride.

“You’ve got the people who were hardest on themselves in the toughest economies,” Hochschild said, “and people who are easier on themselves in a more prosperous economy.”

Shame was the animating force beneath the fire that was lit in Kentucky. Paradoxically, although most of the townspeople rejected Heimbach as “too extreme,” and he later recanted much of what he said, many in town also came to support Trump, whose rhetoric increasingly veered toward that of Heimbach.

Many of Hochschild’s sources came to believe that the jobs and self-worth they’d lost were actually stolen, much like how Trump led millions to believe the 2020 election had been taken from him.

Alex Milan Tracy/Sipa USA via AP

A career seeking common ground

Stolen Pride is Hochschild’s 10th book, and the latest chapter of a career spent understanding and advocating for marginalized or overlooked groups. Hochschild sees the ongoing support for Trump as a “Thermidorian Reaction to all the things I ever stood for and worked for.”

“The first part of my career looked like it was building on values [of equity and justice],” she said. “And in the second, I’m looking at the reaction against those values.”

A professor emerita, she said she credits her success to her decades with Berkeley’s Department of Sociology, a place she calls her “moral home.” It’s where she said she learned the importance of turning off her “alarm system” when interviewing people with views in direct opposition to her own.

I’m always trying to reach for what we have in common.

Arlie Russell Hochschild

While in deep-red eastern Kentucky, amid a swirl of 2020 election conspiracies there, she recalled the reactions she received when she introduced herself to conservative locals as a professor from Berkeley.

“There’s no worse credential in the world, from their point of view,” she laughed. “One man said, ‘Well, you know, there are a lot of stereotypes about us hillbillies here in Appalachia.”

Hochschild said she’d smile and pause, then say, “Yeah. I know there are a lot of stereotypes about people from Berkeley, California.”

In that rare moment within a deeply polarized America, they’d both laugh. They had at least one thing in common. And that, she said, remains a core pursuit of her work — regardless of how challenging the topic or how much the rhetoric and policy may be an affront to her own beliefs.

“I’m always trying to reach for what we have in common.”