Berkeley Talks: Legal scholars on free speech challenges facing universities today

September 20, 2024

Follow Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. See all Berkeley Talks.

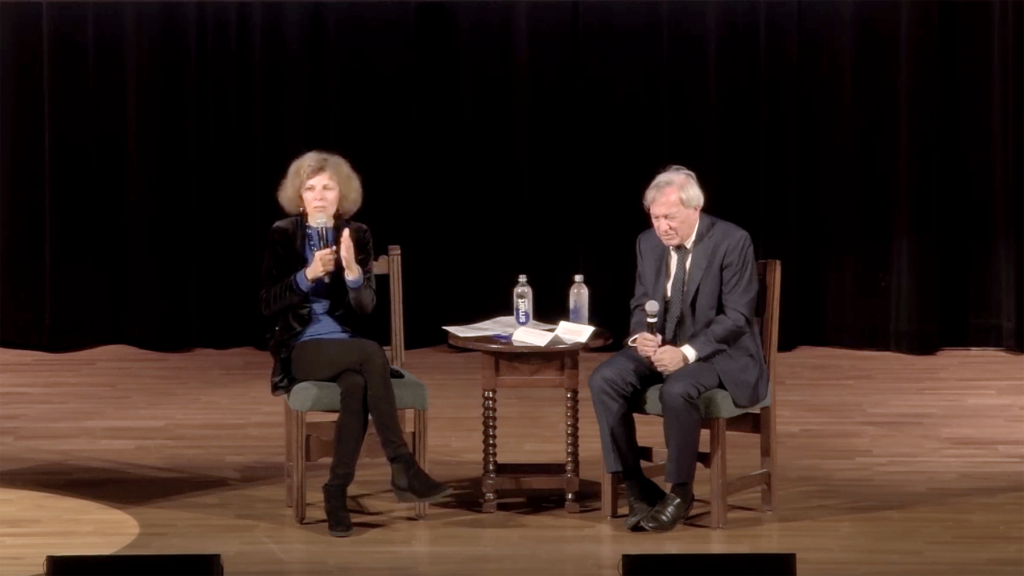

Screenshot from HxA Berkeley video

In Berkeley Talks episode 209, renowned legal scholars Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of Berkeley Law, and Nadine Strossen, professor emerita of the New York School of Law and national president of the ACLU from 1991 to 2008, discuss free speech challenges facing universities today. They covered topics including hate speech, First Amendment rights, the Heckler’s Veto, institutional neutrality and what steps universities can take to avoid free speech controversies.

The conversation, which took place on Sept. 11, was held in celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement, in which thousands of students protested successfully for their right to free political speech at UC Berkeley. Instead of having a moderator, the speakers were given a list of questions they posed to each other, and took turns answering them.

At one illuminating moment, Chemerinsky asked Strossen what steps she might take to reduce the harmful effects of polarized political speech on campus.

“I think that punishment is not an effective way to change somebody’s attitudes,” Strossen answered, “which is what we are concerned about, especially in an educational environment. Treating somebody like a criminal or even shaming, shunning and ostracizing them is not likely to open their hearts and minds. So I think it is as ineffective as a strategy for dealing with discrimination as it is unjustified and consistent with First Amendment principles.

Kefr4000 via Wikimedia Commons

“But there are a lot of things that universities can and should do — and I know from reading about your campus, that you are doing … It’s gotten justified nationwide attention.”

Strossen went on to emphasize the importance of education, not only in free speech principles, but in other civic principles, as well, like the history of discrimination and anti-Semitism.

Beyond education, Strossen said, “universities have to show support for members of the community who are the targets of hateful speech by raising their own voices, but also by providing psychological and other counseling and material kinds of support.”

The event was sponsored by HxA Berkeley and Voices for Liberty, of George Mason’s Antonin Scalia Law School. It was co-sponsored by Berkeley Law’s Public Law and Policy program, the Berkeley Liberty Initiative and the Jack Citrin Center for Public Opinion Research.

(Music: “Silver Lanyard” by Blue Dot Sessions)

Intro: This is Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. You can follow Berkeley Talks wherever you listen to your podcasts. New episodes come out every other Friday. Also, we have another podcast, Berkeley Voices, that shares stories of people at UC Berkeley and the work that they do on and off campus.

(Music fades out)

Julia Schaletzky: Welcome everyone. It’s my great pleasure to welcome you all tonight for a wonderful event. My name is Julia Schaletzky. I’m one of the co-chairs of Heterodox Academy Berkeley, and we are hosting today with other people a celebration of the 60th anniversary of the historic free speech movement in Berkeley, something Berkeley is internationally famous for.

And we are very, very happy to bring you renowned legal scholars Nadine Strossen and Erwin Chemerinsky to discuss some of the issues of our time around free speech. Welcome Nadine and Erwin. To me, free speech is really like the air that we breathe. It’s easy to take it for granted, and forget about it, and you don’t even know it’s there until it’s not. And then we all notice. So, I think we’ve all seen over the last year, universities across the nation struggle with where to draw the line correctly between free speech and harassment, between academic freedom and the indoctrination.

And also we’ve witnessed in my mind, concerning willingness of large groups of intellectuals to support censorship on a large scale, to not engage with opinions they don’t like, even censorship of objectively true facts, which concerns me as a natural scientist. So, it’s very important that we think thoroughly about the concepts, about the legal philosophy that’s the underpinning of this, and why this is so relevant still today. This is one reason why we organize this event together with many supporters that I want to name.

So, first of all, I would like to thank our co-sponsors today, Public Law and Policy, and Berkeley Law, and the Berkeley Liberty Initiative, as well as the Citrin Center. And I would like to name some people that were really pivotal in making this event happen. Shiloh Johnson, Brad Barber, the interim director of Public Law, and Policy Program at the School of Law, my co-chairs at Heterodox Academy, Everett Wetchler, and most of all, Smriti Mehta. Can you stand up? Where are you? Over there. Who has worked literally tirelessly to get this event off the ground? So, I think without Smriti, none of us would be here today.

So, before we start with an undoubtedly super interesting discussion, we would like to begin with a film that was made, a documentary about the historic event of the free speech movement. And I can give a little bit of an introduction to this. The movie is called Bodies Upon the Gears, a quote from Mario Savio, which by the way, preparing this event I learned one of my collaborators, and colleagues studied with Mario Savio at San Francisco Physics, and was his lunch buddy.

So, I have a meeting scheduled to learn more about Mario Savio, and what he was really like, but this is amazing here in Berkeley, you meet these people all the time that have these connections. And the movie today is the first ever screening of a documentary by American Focus and FIRE, the foundation for individual rights, and expression. The film was produced by Alan Casey Wagner, and Paul Wagner, and written, directed, edited by Paul Wagner. Nadine Strossen, who’s here today narrated the documentary, and the filmmakers received research assistant from Bella Sonnen who’s also here, who did all the research. So, please stand up Bella, and Nadine, also.

And Bella is a student here, and went into the archives to get all this stuff. So, if you have questions afterwards about some little known facts about the free speech movement, please approach her, and ask. So, with that, I don’t want to take any more time. Let’s take a look at the movie, and then I’ll be back, and we introduce the speakers for the panel discussion in a fireside chat.

Welcome everyone. Every time I watch this, I take away something else. Today it hit me when he said, “Free speech comes with responsibility, and should be exercised with responsibility.” That nuance, I never realized that before, so, that Mario Savio said, that is not often emphasized.

So, with that, I’d like to welcome you again now introduce our wonderful speakers today. So, first of all, our guest of honor Nadine Strossen, New York Law School Professor Emerita, past national president of the American Civil Liberties Union, and a leading expert, and frequent speaker, and media commentator on constitutional law, civil liberties.

And she has testified before Congress on multiple occasions. Nadine also serves on the advisory boards of the ACLU Academic Freedom Alliance Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, also known as FIRE, Heterodox Academy, and the National Coalition Against Censorship. The National Law Journal has named Nadine one of America’s hundreds hundred most influential lawyers, and she also published a book of our on top of all of these things, 2018, it’s called Hate: Why We Should Resist it with Free Speech, Not Censorship, clearly ahead of its time, 2018. It was selected by Washington University as a common read for 2019. So, welcome Nadine. So, good to have you here today.

I’d also like to welcome Erwin Chemerinsky, which we all know, and he’s one of our leading voices on free speech, and constitutional law at the university, and we are all very, very proud to have him as part of Berkeley. He’s the dean, and Jesse Choper distinguished Professor of Law at the University of California Berkeley School of Law.

Prior to assuming this position, he was the founding dean of the University of California Irvine School of Law, and a professor at Duke Law School, University of Southern California Law School, and DePaul Law School. He’s the author of 12 books, and over 250 law review articles. He’s a contributing writer for the opinion section of the Los Angeles Times, and writes regular columns for the Sacramento Bee, the ABA Journal, and the Daily Journal, and frequent op-eds in newspapers across the country. In 2016, he was named a fellow of the American Academy of Arts in Sciences in 2017, the National Jurist Magazine, again named Dean Chemerinsky as the most influential person in legal education in the United States. It’s an honor to have you both here today, and thank you so much again.

Erwin Chemerinsky: It’s such an honor, and privilege to be here. It’s very special to be with Nadine. We’ve been friends about 40 years. I remember we were in San Antonio at a conference together, and going for a long walk along the river, and you were talking about whether you were going to think about being president of the ACLU, and I was trying to think about what I wanted to do when I grew up. So, it’s really such a pleasure to get to do this with you.

We were given a list of questions, and rather than have the moderator pose the questions we’re asked to present them to each other, and to do this as a conversation. So, I think we’re going to take turns reading the questions, take turns answering them in the responding to one another.

So, the first question that we were given is: Free speech has recently become quite controversial, even among traditional supporters like faculty, and students. Why is this happening, and how can we rebuild trust in the value of free speech?

Nadine Strossen: Well, thank you so much Erwin, and it’s always a special joy to be able to converse with you. I have been learning from you for 40 years both in these kinds of personal interactions, and through your amazingly prodigious, and insightful writings.

I want to say, before I answer the excellent question that came from our wonderful organizers, I want to add one footnote. We law professors love footnotes, right? One footnote about the film, which is the major filmmaker Paul Wagner specifically asked for, he assumed that there would be experts in the audience, including some of you who might have actually been involved. I’m not going to name names, so I have at least one friend in the audience who was proudly in the group of students who demonstrated, and were arrested. And Paul, in a spirit that is so resonant with Heterodox Academy, very humbly said, “I may have made mistakes, I may have made errors. There may be something in the film that’s misleading, please give me constructive criticism.” So, that’s his invitation to all of you.

Now, as to the embattled state of free speech, Erwin, I in part am going to do something. We law professors always ask our students not to do, not to fight the question, but in fact, throughout my many decades now on the forefront of free speech controversies, it has always been a tough battle. And contrary to a lot of questions I get about, Isn’t it different that liberals, and people of the left now are resisting free speech? You and I know that every decade there have been particular issues where liberals want to restrict speech. There’s a very common saying that most people tend to believe in freedom of speech for me, but not for thee. And the only difference has been which particular kinds of speech are seen as so dangerous to particular segments of the public that they are advocating for restrictions.

That said, I think that the problem has intensified in some ways in the recent past, insofar as a number of institutions that have traditionally been very unusually supportive of speech have become less so. That’s certainly true of academia. It’s also true of publishing, of journalism, among librarians. And part of me, a big part of me says, Well, it’s good we should question everything, including the virtues, and vices of free speech. We shouldn’t just repeat First Amendment principles as dead dogma.

So, I do welcome the challenges, and I also like to look at the positive impulses that, in part, are leading to questioning of free speech. And what I’ve seen Erwin, of course, I’m so interested in your reflections as well, what I do not take for granted are the enormous increases of concern and commitment on the part of students and other members of the campus community about equality, about … I know in some quarters it has become a very controversial concept, but about the underlying values of diversity and equity and inclusion.

And a real concern to make sure that the university is open and welcoming to everybody regardless of who you are, regardless of your background, and experience. And, I would add, regardless of what you believe. And I think in an impetus to make the university more hospitable, and open to groups to whom it has not historically been open. I mean, we look at these videos of Berkeley in the ’60s, and I think it’s a very striking visual image, that there was a homogeneity, right, in terms of race and seemingly in terms of religion, in terms of the lack of religious garb and other kinds of diversity that we would see today.

As we will discuss, I think that it is not at all necessary to restrict speech beyond the accepted First Amendment limits in order to promote diversity and inclusivity of every sort. To the contrary, I think that restricting speech does more harm than good, but I do want to salute what I think is the positive animating force behind a lot of calls for restricting speech.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Overall, I think there is a very strong commitment to free speech on the part of students, faculty and administrators. I’m teaching a large First Amendment course in the law school this semester. I taught an undergraduate class about a year ago that covered free speech. And so I think the premise that there’s a waning commitment to free speech isn’t accurate. When we saw the film, we saw that the administration of the University of California Berkeley didn’t believe there should be discussion on campus, the ability to engage speech unrelated to campus activities. No campus administration would take that position today. That reflects attitudes with regard to free speech really have changed. And so let’s start there.

I also agree with Nadine, there’s always the impulse of people to want to censor the speech they don’t like, and that occurs today as well. To the extent that I see in students some waning in commitment to free speech, I think it’s a complicated story.

Some of it is we do a poor job of civic education in this country, and so students come even to a university like this, and even to a law school not understanding some of those basic things about the First Amendment in free speech.

Some of it is, I think the way in which students today equate free speech with the vitriol of social media in the internet. The free speech movement was 60 years ago. That’s as long in time as it was World War I from before. It’s just, it was ancient history to them. And so the Civil Rights Movement, the anti-Vietnam War protest that you, and I remember, that doesn’t resonate with the students today.

I also agree with you that I think some of it is recognizing that there are competing values. Free speech is important, but also having an inclusive community is important, and there’s ways in which those are in tention. So, I think it’s a complicated story, not a simple one.

Nadine Strossen: May I just add one point, or one to underscore the lack of knowledge about government and about freedom … the Constitution, including the First Amendment and what freedom of speech actually is. I think a lot of the hostility toward free speech stems from a distorted, caricatured version of it that is often put out there in the media, including through politicians who have graduated from law school,and should know better.

So, I can’t tell you how many times I have heard, including in reputable mainstream media organizations statements such as, “Oh, First Amendment free speech principles are ridiculously absolute, and there are no exceptions whatsoever, and you free speech defenders are so extreme, you won’t even acknowledge that speech can do any harm.”

And my comments in response to all of those allegations are, “No, no and no.” Now, I have always distinguished my roles as educator from that of advocate. My students know my mantra is they’re not going to do well unless they’re able to understand, articulate and advocate all plausible perspectives on all issues, including the negatives of free speech and the arguments for restrictions. Obviously, in my advocacy capacity, I’m always arguing for the broadest view of free speech.

But what I have found, Erwin, and I’d be curious to hear if you’ve had this experience, is that there really is an overlap between education, and information, and understanding about free speech and support of it. Because the more you understand the history that gave rise to it, and what the consequences were of lack of free speech, not only upon students, but upon the civil rights demonstrators, the anti-war demonstrators, every advocate for every human right, and every social reform, including progressive causes throughout history. Once you understand that, once you understand that far from being ridiculously absolute, our free speech principles do allow the restriction of the speech that is the most dangerous, the more support there is for it. So, everybody should be required to take Erwin’s First Amendment course.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Do you want to do the next question?

Nadine Strossen: OK, so the next question for Erwin. Earlier this year, pro-Palestinian students disrupted a celebratory dinner for graduating students at your home, and protesters claimed that they had a right to speak at a university gathering. Is that correct? And what’s your response? You were also the subject of an anti-Semitic flyer. So, this is a compound question. Is hateful anti-Semitic speech permitted under the First Amendment? When does speech cross the line from being protected to punishable? Now, the full answer you will get by taking Erwin’s great semester-long course, but here’s the soundbite version.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me start with the latter part of that question, because it’s much easier for me to talk about. Hate speech is generally protected under the First Amendment. One of those frequent questions I get, and I’m sure you get, is where is the line between free speech, and hate speech? And the answer is that’s a false distinction in the United States, that whereas in European countries, there are generally laws that prohibit hate speech. The United States Supreme Court time, and again is made clear that even hateful expression is safeguarded under the First Amendment.

There was a Supreme Court case in 1992 R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, and it involved St. Paul ordinance that prohibited burning a cross or painting a swastika, vile symbols of hate in a matter likely to anger, alarm or cause resentment. The Supreme Court unanimously declared that unconstitutional.

In the early 1990s, over 350 college universities adopted hate speech codes. They were all well-intentioned. Everyone to come to court without exception was declared unconstitutional. In part, it’s because they were vague, and overbroad. Campuses couldn’t find a way of defining what was hate speech in a manner that wouldn’t violate the First Amendment principles there to vagueness, and over-breadth.

And in part, in the core of the First Amendment is that all ideas, and views can be expressed, and hateful ideas are included in that protection. Nadine has written a terrific book on hate speech that explores, and explains this. Now, that doesn’t mean, as Nadine just said, that free speech is absolute. If it crosses the line and becomes incitement of illegal activity. If it becomes a true threat, it’s unprotected, but there are legal tests for that that have to be met.

Now as to what happened at my house on April 9, a little bit of context, my wife, and I do a dinner for all the entering students at the beginning of the school year and usually do it over many nights. We didn’t do such a dinner in the fall of 2021 because of COVID restrictions. And so the presidents of the third-year class came to us, and said, Would you host dinners for us to celebrate our graduation? And we agreed to do that, and schedule them on April 9, 10 and 11.

The week before those dinners, a poster went up on every bulletin board in the law school. It was a caricature of me holding a bloody knife and fork with blood around my lips saying, “Boycott Zionist Chem.” Now, as you know, one of the horrible anti-Semitic tropes is blood libel, and one of the scary and terrible things that’s come out in the last year is this trope has resurfaced. A recent report in terms of what occurred on the Stanford campus, talks about how blood libel had reemerged there.

The poster didn’t complain about anything that I’d said or done. I’ve taken no public position with regard to the war in Gaza. The law school doesn’t have a foreign policy, doesn’t take positions. It’s not my field. The only thing that the poster demanded was that the University of California divest, and of course, the law school has no policy and isn’t involved with that at all.

The night of the dinner, the students who were responsible for that poster surprised me by attending, and I have to tell you, my first thought was given that they called for a boycott. I hope that there’s not going to be any disturbance. And then I thought, “That’s unfair of me. Isn’t it wonderful? They decided to come anyway?” We greeted everyone in front of our house, and people go to the back. There’s about half hour conversation before dinner. Everyone went through a buffet line and sat down with their dinners.

As soon as everybody had taken the dinners, the student who was responsible for the poster took a microphone out of her backpack, went to the top of the steps in our backyard, and began a very pro-Palestinian speech. I immediately went to her, and said, “Please stop. This isn’t the place for this. Please leave.” She didn’t. She continued. My wife grabbed the microphone. It was recorded. It all went viral. It became national news. We received many, many death threats, thousands of hate messages, also some supporting messages.

So, now your question, what about the First Amendment? Even if this event had occurred at school, it wasn’t a First Amendment right that was involved here. There’s no First Amendment right to disrupt activities. If we had had this dinner in the law school, and she had taken out her microphone, we say, “No, you don’t have a First Amendment right to do this.” The law is clear that … it’s legally called a limited public forum. You can limit what the speech is about. There’s never been a speaker at a dinner at our house. No prior student have done this. My wife, and I have never spoken. It’s just a dinner. So, there’s no First Amendment right to disrupt.

Moreover, this is private property. It’s our house. Under California law, and it’s clear once we asked her to stop and leave, she was a trespasser, and she had no right to be there. It’s been enormously painful for my wife and me to have gone through this. It’s hard to even describe what it’s like to be the subject of something going viral in this way. It’s hard to describe what it’s like to get, not dozens, but probably hundreds of death threats, and thousands of hateful messages. So, it’s hard to talk about, but that’s what happened.

Nadine Strossen: Thank you so much, Erwin for, I mean, among other things, for opening your home to your students for celebratory dinners, that’s so special, and for sharing your personal experience. It segues into another type of permissible limit on free speech, illustrating the sensible nature of the law. As Erwin already alluded to, speech may never be restricted solely because of disapproval or dislike, no matter how strong, no matter how widespread of its content, of its message, of its viewpoint.

If however, you get beyond the content, the hateful message, the anti-Semitic message, and the anti-Palestinian message, any message that is controversial, and you look at it in its overall context in what is often described as the emergency concept, the Supreme Court sensibly has said if a hateful message or message with any other content in particular facts and circumstances, either directly causes specific harm, such as a fraudulent statement or a defamatory statement, or it imminently threatens certain specific serious harm, such as the intentional incitement or true threat that Erwin mentioned, then it can and should be punished.

So, much hateful speech, including I think the paradigmatic examples of hateful speech that people have in mind when they say, “Hate speech should not be protected,” the kind of face-to-face, verbal epithets, those are already subject to punishment under our law. But when you get beyond that to say a hateful idea because we dislike the idea, that is such an inherently subjective concept.

Now, all of us may know what we hate, but let me tell you, in the recent past, Black Lives Matter advocacy has been attacked, including by government officials as hate speech, hate speech against police officers, hate speech against white people. On some campuses, the phrase All Lives Matter has been attacked as hate speech, and even the phrase, “free speech” has been attacked as hate speech.

So, I mean, when you have such a subjective concept, by definition in our society, those who wield power are accountable appropriately to majoritarian interests, and they predictably are going to wield that subjective power in ways that do not favor the messages of the minority groups, whether minority political perspectives, minority races and so forth.

We heard Martin Luther King’s eloquent advocacy of free speech, which he was imprisoned for exercising. Most people know that Martin Luther King wrote a famous letter from a Birmingham jail, but they don’t realize that his crime was what we now consider to be some of the most important speech in a democracy. And I think that is really important that we explain what the actual consequences would be, that speech that you love may well be deemed to be hateful speech and subject to suppression.

Erwin Chemerinsky: You would ask me question two and A on this, let me pose to you then question 2-B that we were asked to discuss.

Nadine Strossen: To be or not to be. (Laughs)

Erwin Chemerinsky: Exactly. What steps would you support to reduce the harmful effects on a college campus? What I think is the most important legal issue right now, how should universities address the tension between free speech in Title VI and Title IX?

Nadine Strossen: So Title VI and Title IX, to oversimplify a bit, require universities to provide non-discriminatory environments for all students, and they have a responsibility if they are in notice of conduct, including expressive conduct, that creates a hostile environment, such that that is sufficiently, objectively, and subjectively offensive, and sufficiently severe or pervasive, that it undermines equal educational opportunities, universities have an obligation to investigate and takes steps to remediate.

But the remediation, as Erwin and I were discussing in emails prior to this event, need not, and I believe strongly, should not include punishment of speech that would be constitutionally protected. I think that punishment is not an effective way to change somebody’s attitudes, which is what we are concerned about, especially in an educational environment. Treating somebody like a criminal or even shaming, shunning and ostracizing them is not likely to open their hearts and minds. So I think it is as ineffective as a strategy for dealing with discrimination as it is unjustified and consistent with First Amendment principles.

But there are a lot of things that universities can and should do, and I know from reading about your campus, that you are doing, including under the great leadership of your former chancellor Christ, which I have followed, it’s gotten justified nationwide attention.

And education, education, education, including education not only in free speech principles, but also in other civic principles. Education in the history of discrimination, including Erwin, I think the history of anti-Semitism and anti-Semitic tropes, but also of other kinds of discrimination. One of my friends, several decades ago, was actually the founder of a then new interdisciplinary field of hate studies. And truly, this involves every field from A to Z, anthropology, zoology, and everything in between. If we are to try to figure out how to counter the development of hateful and discriminatory attitudes, we need to know what generates those attitudes in the first place, and universities are in great position to do that.

Universities have to show support for members of the community who are the targets of hateful speech by raising their own voices, but also by providing psychological and other counseling and material kinds of support.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I would say the same thing. Let me phrase it a slightly different way. I’d start what you do. Title VI says, “Recipients of federal funds cannot discriminate on the base of race or national origin.” The Supreme Court, the Department of Education has said this also includes prohibitions with regard to anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

The prohibition is also one that stops there being harassment or a hostile audience on these grounds. Title IX says, “Educational institutions that receive federal funds can’t discriminate in the basis of sex.” This also prevents harassment in a hostile audience.

The Assistant Secretary of Education, Catherine Lhamon, who oversees the Office of Civil Rights, has said repeatedly over the last year that even speech that’s protected by the First Amendment can create a hostile environment that violates Title VI or Title IX. The Office of Civil Rights has issued letters to universities, such as the University of Michigan, Brown University, City University of New York, making clear that their deliberate indifference with regard to anti-Semitic speech was a violation of Title VI.

Now, the standard, legally, under both Title VI and Title IX, is it a campus, wherever we’re talking about, cannot be deliberately indifferent to the hostile environment or the discrimination. And the difficult question right now that every campus faces is, what must it do to avoid being deliberately indifferent?

Lhamon’s Dear Colleague Letter in of 2024 was clear that a campus, if it’s a public university, cannot punish speech that’s protected by the First Amendment, but it must take other actions to avoid deliberate indifference. Let me give an example, because a case that I was involved in litigating, it’s a case called Feminist Majority Foundation v. Hurley.

Nadine Strossen: Which is cited in the letter, Erwin.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Right.

Nadine Strossen: Yeah.

Erwin Chemerinsky: [It] involved Mary Washington University, a public school in Virginia, and there was a debate on campus as to whether allow Greek life, and three women wrote an op-ed in the campus newspaper opposing Greek life, saying with their fraternities on campus, there’s more sexual violence against women. They then got targeted over a then-existing social media platform, Yik Yak. Over 600 messages were sent to them, incredibly vile messages, some threatening them with rape and murder. They went to the campus administrators and the campus administrators said, “This is anonymous speech over social media. We can’t do anything about it.” The campus even posted on its campus website that it wasn’t responsible for anonymous speech over social media.

The women, through the Feminist Majority Foundation, sued the university. The federal trial court ruled in favor of the university, saying, “This is speech, it’s protected by the First Amendment. There’s nothing a campus can do.”

I represented the women in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit and we prevailed. What the Fourth Circuit said, and it’s right, is that the campus can’t be deliberately indifferent. It has to take actions that are reasonable under the circumstances. And it gave a list of what those could be.

And Catherine Lhamon and her Dear Colleague Letter in May listed some of those things. Some of it is speech by campus officials, that campus officials have the bully pulpit, and there’s times when they need to speak out and condemn racist or anti-Semitic or sexist or homophobic acts. There can be protection provided to students, in this instance, it would’ve been appropriate to do so. There can be mental health support provided to students. There can be trainings provided, there can be educational programs.

And when you look at the cases that have come down just in the last month, such as one against Harvard University, where the federal court refused to dismiss the action, saying it had been deliberately indifferent. What’s enough to avoid a conclusion of deliberate difference? The law isn’t clear about this, but the legal standard is a campus can’t choose to do nothing.

Nadine Strossen: And some of us who are equally committed to freedom of speech and providing a campus that is not deliberately indifferent to any kind of discriminatory conduct, are concerned that campuses not be given too great an incentive to over-regulate speech, because vile, as anti-Semitic or other discriminatory or hateful expression is, it is protected, and it could not be suppressed consistent with the vibrant kinds of debate and discourse that we want to have on campuses.

So I took heart, Erwin, in one of the statements in that Dear Colleague Letter, in which Catherine Lhamon said, “The university may, however,” after listing what they should do, “the university may, however, be constrained or limited in how it responds if speech is involved.” Now that’s tentative language, but I think it’s something we have to be very cognizant of.

And I also want to make another point, which is that I think that, yes, there is a tension here, but it’s a tension that is inherent in the concept of free speech itself, because no member of the university community can meaningfully, freely, vigorously engage in free speech if they are subject to hostile environment harassment. If they are subject to expression that is so severe or pervasive that it, in effect, intimidates them and chills them and deters them from exercising their free speech rights.

And that’s what I found so disturbing about the allegations. And in fairness in the Harvard case, we’re only talking about allegations at this point. They haven’t yet had to go to trial to prove them, but if those allegations were true, the students who were targeted by certain kinds of expression would themselves be impeded in meaningfully exercising their free speech rights.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Do you want to pose the next question?

Nadine Strossen: Yeah, I have to pose the next question, which is the controversies … Oh, this is something we’ve debated in the past, Erwin. The controversies that have unfolded this past year due to the Israel-Palestine conflict have highlighted the risks of allowing institutions to be instrumentalized for political advocacy. Consequently, there is growing support for universities to adopt institutional neutrality, in line with the University of Chicago’s 1967 Kalven Report. Do you endorse this approach?

Erwin Chemerinsky: Generally, no. I think it’s a complicated question to answer in a yes or no way. But let me say why I said generally no. Institutions aren’t neutral. This institution has a wonderful statement of principles of community, and I think that that is what it should do. That’s not being neutral. We’re not neutral in terms of our values with regard to scholarship. We’re not neutral with regard to our values as regard to teaching. So automatically I say well, no, an institution can’t be neutral.

Well, I think what this is more about is should university officials, the campus in some way, take positions? And I think the key is when is silence the wrong message? Let’s take after the tragic death of George Floyd. I felt it was very important, as a dean of a law school, to send out a message to the community that recognized the pain that people were suffering, and that tried to provide some way of unifying our community.

Chancellor Christ sent out a message then that was so important for the university. University officials did that. That wasn’t being institutionally neutral. It was using the authority as best as a chancellor dean to say something important.

After Jan. 6, I thought it important, as a dean of a law school, to speak out and speak in favor of the rule of law. We had a unfortunate, terrible incident several years ago when Alan Dershowitz came and spoke at the law school. Someone drew a swastika over a picture that was on a bulletin board. I thought it really important, as soon as I saw that, to speak out and say, “That expression of anti-Semitism is fundamentally inconsistent with who we are as an institution and inconsistent with our principles of community.” That wasn’t being institutionally neutral.

So I reject the idea that institutions should somehow pretend to be neutral with regard to things. That doesn’t mean that institutions should take positions on all issues. I think that there is certainly many instances where it’d be more harmful than constructive for campus leaders to take a position and express themselves. And I think one of the hardest questions that any campus officials face is when to take a position and when to be silent. But I wouldn’t say that there should be a rule with regard to silence. If somebody were to express racism or sexism or anti-Semitism or homophobia in my community, I will speak out against as a dean. I won’t be neutral about that.

Nadine Strossen: Well, obviously I defend your right to do that, Erwin. And you may recall, we’ve talked about this over the years, and my views have fluctuated, but unlike a number of other people and importantly, university leaders that have moved toward adopting new policies of institutional neutrality, I am persuaded that that is a net benefit.

And it doesn’t … Let me be very precise. It is neutrality with respect to issues that do not directly affect the university itself. So if the state legislature is considering, as unfortunately too many of them are, legislation that would violate the academic freedom of the institution or individual faculty members, the university should speak out about that.

But other issues, no matter how compelling and important, as the issues that Erwin mentioned, I am convinced that the Kalven Report was correct when it said, “If we are serve our distinct, unique role in society, as the pursuer of truth, the researcher, the disseminator of information and theories, in the pursuit of truth, then we as an institution cannot endorse any perspective institutionally, with respect to contested political, and social, and cultural issues.” That is for the individual members of our community. Yes, faculty members and students should speak out on all of these issues. And we believe that they can only do so with full freedom and full pluralism and diversity of perspectives, if we as an institution do not endorse an institutional orthodoxy.

Quite frankly, I think another reason why Harvard and Stanford, among others, that have recently adopted this kind of perspective is a more pragmatic one, but a very significant one that also has to do with conserving the precious resources of the university, of which the most precious, is the time and attention of its leaders, as we have seen the endless amounts of time that have gone into formulating and reformulating and defending both the issuing of statements and the non-issuing of statements.

And one of my favorite lines in the Kalven Report, and I’m not going to do it justice by paraphrasing, toward the end, it says that, something like this, that universities are always going to be second-rate politicians. So please conserve your resources for your own special mission, the pursuit of truth. And toward that end, hold the institutional tongue to free up, maximally, the tongues of the individual community members.

Erwin Chemerinsky: It’s tempting to respond, but I’ll ask the next question. How does academic freedom differ from freedom of speech? Is placing limits on faculty expression in the classroom, such as prohibiting them from indoctrinating students or expressing personal opinion irrelevant to the course content, infringe on that academic freedom?

Nadine Strossen: Another question for an entire semester. Let me say, I think one of the best discussions of some of these issues is in the current issue of the Harvard Alumni Magazine, an article by my Harvard College classmate, Lincoln Kaplan, based on extensive interviews of my esteemed co-panelist, Erwin Chemerinsky, and Robert Post, who formerly taught at Berkeley Law School, and was the former Dean of the Yale Law School. And they have very different perspectives on some of these questions, which I’d love to hear Erwin’s comment about.

But let me say this, that academic freedom refers to … Well, first of all, it has no specific legal definition under the First Amendment. I think the best definition is in two statements by the American Association of University Professors, the AAUP in 1915 and 1940, with some slight amendments. And basically, it is to preserve the freedom of research and teaching and discussion on the part of faculty members, and also to some extent, on the part of students for the purpose of pursuing truth.

That has some overlap with freedom of speech, but there are some distinctions, and it gives me an opportunity to talk about another sensible limit on free speech that the First Amendment recognizes, which is often referred to as content neutral or viewpoint neutral time, place, and manner regulations. So in a university classroom, and Erwin responded to this in part, when he answered that question about the invasion, the trespassing, on his home property. In a classroom about constitutional law, it would be inappropriate, not only for anybody to discuss any perspective with respect to the Middle East, but for that matter, any perspective with respect to mathematics, literature, anthropology, or tort law. You can have a restriction that confines the expression of the professor and the student to the particular educational mission and educational responsibility.

Also, we, faculty members and administrators, have a responsibility to make content-based judgments and rejections of expression by our peers and by our students if we think it is not consistent with the governing norms of that academic field, or if it is subpar or if it’s plagiarized, if it’s not well written.

And so, the norms of academic freedom are professional norms. They are not the open-ended Hyde Park corner kinds of norms of free speech, that anybody can express any opinion.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think the key word in what Nadine just said is, “overlap.” I think from a Venn diagram sense, the First Amendment and academic freedom are overlapping circles. There’s some things that are protected by academic freedom, but not by the First Amendment. The First Amendment applies only to government institutions. The First Amendment doesn’t apply to private institutions. Now, the private institution may have a commitment to open inquiry and free speech as a result because of academic freedom, because of what it puts in its faculty and student handbooks, but it’s not the First Amendment. It’s a private institution.

And there are some things that are protected by the First Amendment that I would say aren’t part of academic freedom. A professor on his or own time going to rallies over the weekend, I think there’s a First Amendment right. It’d be wrong for a public university to punish that, because it is speech protected by the First Amendment. But if it’s not part of the academic inquiry, I’d say, that’s not academic freedom.

On the other hand, especially for a public university, there’s much that we would say is protected by both the First Amendment and by academic freedom. If a professor were disciplined because of taking unpopular positions in scholarly articles. I think there’d be a first amendment issue and an academic freedom issue. The important thing in response to this question to remember is just like freedom of speech, academic freedom isn’t absolute. If we were to assign a professor to teach contract law and he were to object and say, “No, I’m just going to come in and there’s a protest against that.” Talk about sports every day. We could discipline that professor and say that, “No, academic freedom doesn’t protect your right to do that.”

If a history course assigned a professor to teach about mid-twentieth century European history and that person denied the existence of the Holocaust, academic freedom wouldn’t protect the ability to do that anymore to protect the right of a biology professor to deny evolution or a geology professor to teach it’s a flat earth. You have to meet responsible academic standards. Academic freedom doesn’t provide protection. Now the hard part of the question, I think, is where is the line to be drawn between impermissible indoctrination and permissible exercises of speech and permissible exercise of academic freedom?

Regents policy prohibits professors from engaging in indoctrination in the classroom. On the other hand, no professor [inaudible 00:53:27] he or she tries can be completely neutral. The values and views of the professor influence what material is taught, how it’s taught, and it inevitably comes through. There’s easy cases. If a professor were to say to the students, “You get extra credit for going to this political rally.” That obviously crosses the line. If it’s a class, I’m going to make it about calculus. And the professor wants to come in and talk about controversial political issues, totally unrelated to that.

That crosses the line, but where the line is drawn in the hard cases, to me, that seems incredibly difficult.

Nadine Strossen: Did you say that was our last question, Erwin?

Erwin Chemerinsky: No.

Nadine Strossen: We can still keep going.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Keep going.

Nadine Strossen: Good. Somebody’s going to tell us when we’re running out of time. The next question, here’s an easy one. These are all great questions and we’re only able to give the surface. In the last decade, we’ve seen an increase in cancel culture and academic boycotts from both sides of the political spectrum. On one hand, publicly criticizing someone could be considered an exercise of free speech. On the other hand, it may be considered a violation of others’ rights to free expression and academic freedom. Where do you fall on this issue?

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think it’s enormously important to draw a distinction between government sanctions with regard to speech and social pressure with regard to speech, and I think this question doesn’t fully recognize that distinction. If the government, and that includes the University of California or any public university, goes to punish a student or a faculty member for expression, that’s a First Amendment issue. But if students put pressure on one another not to express certain things, that social pressure is not a First Amendment issue. We all learn from a young age that it’s inappropriate to say some things in particular places. That social pressure isn’t inherently undesirable.

Now, I worry very much in the context of the classroom that social pressure can stifle speech. When I talk to students at orientation, I try to express to them how important it is that all ideas and views get expressed. That if they, through social pressure shut it down, then they’re losing something because lawyers, they need to know the arguments on all sides. But nonetheless, social pressure, which this question calls cancel culture, isn’t a First Amendment issue. We need to try to make sure that we do what we can to minimize the social pressure, but we shouldn’t equate it by any means with what we’re talking about earlier, which is the government violating freedom of speech or university violating academic freedom.

Nadine Strossen: I agree with Erwin, of course, that social pressure should not be equated with government pressure. I also though believe that meaningful freedom of speech should not be equated with only what the First Amendment guarantees.

To be sure, we should be free from unjustified government restrictions of free speech. But in my view, and most importantly in the experience that has been documented on campuses around the country and in our society generally, it is necessary but not sufficient to stop government restriction if we are to have a meaningful, thriving, robust free speech culture. Every year for five years now. FIRE, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression and College Pulse have been doing very detailed granular surveys of the free speech culture on college campuses.

A new one just came out, so I will cite that. But before I do, let me say that the results have been replicated by Pew and by Gallup and by Heterodox Academy and survey after survey after survey. That we have a climate in our campus communities where one would hope to have the most robust and vibrant and diverse perspectives aired. Where students and faculty members say, “We dare not have a free, frank and candid conversation on our campus about a whole host of subjects.” And those subjects were something like the last survey just came out last week, more than 40% of students across the country said, “We cannot have a frank and candid conversation on our campus about abortion, about gun control, about immigration, about police issues, anything to do with race or gender.”

And I’m very proud of faculty members because I think all of us do strive very much to not indoctrinate our students. And the survey results consistently show that students say that they are self-censoring, not because they’re afraid that the government’s going to punish them, not because they’re afraid that their professors are going to sanction them in some way, but they are afraid of peer pressure. Now, of course, I would completely oppose any kind of government punishment of criticism. Peer pressure is itself an exercise of First Amendment rights, but we have to encourage our students to not be disproportionately harsh and punitive toward each other for expressing controversial points of view.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I agree with that and I’m a fan of much that FIRE does. I find its rankings of university incredibly arbitrary and I find that their methodology is very arbitrary in this regard and we could have a much longer conversation about it. And I find even the way they phrase the questions to be very loaded. I’ll agree with the conclusion, but I’m very skeptical of what FIRE does in the way it ranks universities. It’s a topic for a different time.

Let me ask you question 5B. 5B, at Berkeley, protesters have engaged in property damage and actual or threatened violence of speakers like Milo Yiannopoulos in 2017 and an Israeli speaker earlier this year. Given these unfortunate instances, isn’t there a justification for canceling some speech and allowing the heckler’s veto for safety concerns?

Nadine Strossen: Before I answer that question just very briefly, in the same spirit as the filmmakers request, FIRE makes all of its data available and intrigues anybody who is critical to please contact them, they actually have had whole seminars with members of the Harvard faculty who are distressed and having been ranked at the bottom two years in a row. So seriously, very, very open to criticism.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Love to have another debate about the FIRE methodology. I don’t think it’s for this time and place.

Nadine Strossen: What I’m saying is they welcome that or win themselves. So heckler’s veto as the term implies, it was a term that was invented, coined by a great free speech scholar at the University of Chicago, Harry Kalven and adopted by the United States Supreme Court. And as the term itself signifies, it is the effect of shutting down a speaker in order to prevent violence or protect against violence that is threatened by those who object to the speaker’s message. To do that is to allow anybody who disagrees with any speaker to have a censorial power.

And the Supreme Court correctly has said that the responsibility of government, including university officials at a state university such as this, through adequate law enforcement resources to protect not only the right of the speaker to convey ideas and information, but also the right of the audience to hear the ideas and information. And I want to give a little history lesson here because I think it’s so important to understand the historical context in which this concept was given rise to.

And that was as is true for so many of our fundamental free speech principles in the context of the civil rights movement because that was exactly the strategy and the argument that was used and used successfully in the lower courts, including state Supreme Courts throughout the South said, “Oh, we’re not going to allow Martin Luther King to demonstrate. We’re not going to allow students to demonstrate peacefully against Jim Crow and for equal rights.” Not because they were threatening any violence or disruption at all, but because of the opponents who were pro segregation and anti-civil rights were threatening and engaging in violence.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I totally agree, and yet I think you oversimplify here. There is no right to disrupt somebody else from speaking. There’s no First Amendment right to use your speech to silence others. There was an incident at Stanford Law School about a year and a half ago, at UC Law San Francisco and at Yale Law schools before that, where speakers came and students shouted so they couldn’t be heard and two of those incidents had to be canceled. There is no First Amendment right for students to use their speech to disrupt others, otherwise it is what you described as the heckler’s veto. And then the only speech we’d ever hear is that which no one cares enough to shout down in silence.

It can’t be. And so in a message I send to students every year in explaining our free speech policy, it’s you can’t use your speech to disrupt events, to stop people from being heard. If you don’t like a speaker, protest in a non-disruptive way, bring in your own speaker. And I completely agree with where you start. That a campus has the obligation to protect those who are coming to speak. So there’s not a heckler’s veto, but where I think there’s an oversimplification is campuses also have a legal and moral duty to protect the safety of students, staff and faculty. And what happens in an instance where despite the best efforts by police protection, the campus can’t protect the safety of student, staff and faculty if they allow the speaker to go forward.

In that instance, I don’t think the campus has an alternative but to cancel the speaker. As difficult as that is, if there is no other way to protect safety and there is then an even a harder question, how much does a campus have to spend in order to protect safety? What is the point at which the campus can say it is just too expensive and takes too much in the way of resources, more educational mission, so therefore we’re not going to allow this speaker to go on. No court has yet answered that question. If I remember right, the free speech week that occurred in the fall of 2017 here, cost the campus about $4 million in security costs.

What if it wasn’t a free speech week? What if it was speech month or semester? And what if the cost wasn’t $4 million but $40 million? All of that coming away from the educational mission of the school. I believe even given my strong commitment to free speech, there was a point at which the campus can say, “That’s too much. We can’t afford the safety costs, therefore we can’t allow the speaker to go on.” It’s the last resort of canceling the speaker. And I don’t know where that line is, but that’s why I say I think it’s too simple to say you just protect the controversial speaker and always allow the speaker to go forward.

Nadine Strossen: And I’m so happy for that clarification because that is not what I intended to say. But much more importantly, that is not what the Supreme Court has held. The Supreme Court has held exactly as Erwin has said. That as a last resort, if there is no other way to prevent the violence, then of course you do have to allow the speaker to be silenced. And the legal way that we phrase that is the least speech restrictive alternative. I also agree with Erwin that universities should not be compelled to spend money that is better used toward other educational purposes.

And I understand that there are steps that could be taken in consultation with university security and larger outside police forces to try to cabin the expense. For example, hosting the speaker indoors, requiring that people who attend have university IDs and so forth. So I think we agree in principle, Erwin. Whose turn is it?

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think I asked the last one. Did you want to ask?

Nadine Strossen: Of course. Of course. Alongside free … This is good because this is a Berkeley question. And by the way, I’m wearing your very pretty Berkeley blue. I read on the website that it is distinguished from Yale Blue, but it’s … I’m going to wear this at Yale next week. Don’t tell them. Alongside free speech, Berkeley also has a history of compelled speech from McCarthy-era loyalty oaths to DEI statements and gender pronoun usage. Does compelled speech undermine free speech and academic freedom? Should I go on to the next …

Erwin Chemerinsky: I can address that and then you can. We require a faculty candidate to do a job talk in order to be considered. That’s a form of compelled speech. No one would object to that. We require a job candidate to provide a statement with regard to their academic agenda, their scholarly work that’s going to come. No one would object to that either. It’s compelled speech. Now, certainly there are times when compelled speech becomes very objectionable. We’re both familiar with the famous Supreme Court case during World War II, West Virginia Board of Education versus Barnett, where the state of West Virginia required children to salute the flag at the beginning of school days.

And the Supreme Court, in a very eloquent opinion by Justice Robert Jackson said that that violates the First Amendment. So sometimes compelled speech is completely acceptable. We require students to take written exams in many courses. That’s a form of compelled speech and sometimes compelled speech is very objectionable. The McCarthy-era loyalty oaths. Now I’m going to get to the more controversial part of the question. What about so-called DEI statements? And I think it all depends on how they’re asked and how they’re used. I think it’s completely appropriate to ask faculty candidates, how will you teach a diverse student body?

Because part of what we’re evaluating them on is how they’re going to be in the classroom. I find nothing objectionable about that. On the other hand, if DEI statements are used to impose a political litmus test and say you have to take a particular position, then I find them objectionable. So it’s not that there’s anything inherently wrong with DEI statements any more than anything wrong with requiring job talks or academic agenda statements. It could be wrong if it’s used in an improper way.

Nadine Strossen: That’s exactly right. And is so true for all of these questions, the proverbial devil is in the details. It depends. I do want to say, add one comment about that historic landmark case involving the Jehovah’s witnesses, which was an ACLU case, I’m proud to say. Every time I reread it, I’m struck by the fact that the Supreme Court explains very eloquently that the autonomy and dignity of the individual is even more compromised by being forced to articulate ideas or so-called facts that are inconsistent with our own beliefs. That is an even more deeply violative intrusion upon our personal autonomy the court said than being stopped from saying something we do believe.

So if these statements can be judged in a way that is not going to be based on value approval or disapproval or even a specific concept I would say of DEI, that’s one thing. But a lot of the information, or let’s say at least allegations or claims that have been made about some of these statements is that there are relatively narrow views of, first of all, what constitutes diversity, equity, and inclusion, for example, not extending to diverse political or philosophical or religious perspectives. That to me is a viewpoint discriminatory concept that would violate the First Amendment.

Erwin Chemerinsky: The seventh and last question on the sheet, and then it gives us the time for questions from the audience. And it’s a wonderful way and you can tell these questions are terrific and we appreciate you’re providing them to us. Chancellor Rich Lyons has recently said, “If there’s a free speech university, it is Berkeley.” Our students have inherited a legacy of free expression and social activism from the free speech movement.

How can we maintain this proud tradition while safeguarding others’ rights to speak freely and to hear diverse perspectives? More broadly, what steps can universities take to improve the state of academic freedom and free speech on their campuses and to maintain an environment conducive to education and research during protests?

Nadine Strossen: We started talking about this at the beginning and I think it’s really wonderful to come full circle. Positively, constructively what all of us can do, including what is being done by Heterodox Academy and the other organizations that are co-sponsoring this wonderful program and by all of you for committing your time both in the classroom and outside of the classroom. It’s a very important educational and cultural acculturation process. What better place to do that than a university? And I look at, for example, we’ve talked a lot about the commitment to DEI or the commitment to counter sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based discrimination where enormous strides have been made in the recent past.

And we think of really reshaping the culture of the institution in ways that include orientation sessions, special classes, special trainings. All of those methodologies could and should be harnessed to promote an equal engagement and commitment and understanding on the part of every member of the community. From the get-go, every single stage of the individual’s interaction with the university, starting with the recruitment materials that you make available to welcome or invite people to apply to this university. You explain how important, how essential academic freedom and free speech principles are.

You advise the students, you don’t warn them. I don’t think it’s a warning. I think it’s a, “Wow, this is an announcement. You are going to be exposed to all kinds of perspectives and ideas that are new. And some of them may be shocking and some of them may be exciting and they’re all going to be enlightening.” And if the student is not interested in that kind of environment, then they won’t come here. In the application materials, I’ve been told by many of my friends who have kids who are applying to colleges and the essays that they are asked to write could be targeted among other topics on this topic. Give us your view, tell us an experience, get them thinking along those lines.

Orientation sessions, students really need to know, and new faculty members really need to know the basic rules and regulations, dos and don’ts of free speech and academic freedom. Surveys not only FIRE’s but other respected surveys have shown that students and faculty members say that they’re actually quite ignorant of what the rules are on their campuses. And in fact, on many campuses, the rules are not clear. They are scattered among many different policies and some of them are inconsistent with each other.

So a constant process of education and not only in the sense of preaching at but through experience. Students have to be given opportunities for debate and discussion, for exercising their abilities, their enjoyment, not only of expressing their own views, but of listening, really listening to and engaging with other people’s points of view.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I’m in my 40th year as a professor, my 17th year as a law school dean. I’m a member of the faculty at five different universities and like Nadine, I speak at dozens of universities over the course of a year. I have never seen a more intellectually vibrant campus than the Berkeley campus. I have never seen a campus more committed to free speech than the Berkeley campus. I think a lot of credit over the years that I’ve been here has to go to Chancellor Carol Christ, who’s here, who I think is a model in terms of what we want, an administrative view with regard to freedom of speech.

In the things that Chancellor Christ did that are a model for other university leaders are the very things that Nadine was talking about. First, it’s essential that the campus articulate its commitment to free speech and academic freedom. It can’t be assumed that those in the university instinctively embrace free speech and academic freedom. As we said, the instinct is often to want to silence the speech one doesn’t like. Second, it’s essential that there be principles of community, that these are aspirational, but it’s important that the values of the community be stated. And we have this at Berkeley.

It’s crucial that there be clear, time, place and manner rules with regard to speech. That there be major events policies that are clear with regard to speech as part of that. Obviously as we’ve said, the time, place, manner rules have to be content neutral. They have to leave adequate places for speech, but the speech is important as it is, can’t interfere with the basic functioning of the campus. And even though all of this is clear, we have to recognize this can be lots of very hard, free speech issues that come up and they’re going to continue to come up. They’ve always been that way and I think the events in the world and on the country make it likely that free speech is going to continue to be an enormously hard issue for this campus and every campus.

(Applause)

Moderator: Time for questions. So if you have a question, just raise your hand and we’ll come find you when …

Audience 1: I want to say first I have a great deal of respect for Dean Chemerinsky and I’ve known him for a number of years. We are acquainted with each other, but I want to say based on the evidence that I saw, which may or may not be sufficient, I have some disagreements with how Dean Chemerinsky characterized those protesters at his house. So I just wanted to say that.

I think the next to the MAGA Republicans, the Israel lobby has become the second biggest threat to free speech in America. I think that Ms. Strossen, when you said liberals want to suppress free speech, I think that is way too unqualified and way too overly broad.

I have, my question in particular is, with regard to the no-mask situation by UC President Michael Drake, which as a Black person, I want to say I was disappointed to see that he’s Black, I’m wondering what you have to say about that because a lot of students at pro-Palestinian protests or demonstrations, I should say, have to wear a mask to protect themselves from threats against their life or assault. And I would also like to know whether either of you think that anti-Zionism is inherently in and of itself anti-Semitism. I am anti-Zionist and I equally oppose anti-Semitism as many anti-Zionists do also. Thank you.

Nadine Strossen: Thank you very much for giving me the opportunity to clarify. Of course, not all liberals, and by the way, not all conservatives or not all members of any group are pro-censorship, but I was just making, I am often asked by journalists, isn’t it true that liberals now are more pro-censorship than they used to be? So thank you for the opportunity to clarify.

On your two other questions, the anti-masking ban, I find this a very difficult issue and let me tell you, I’m not now wearing my prior ACLU hat because the ACLU consistently opposed mask bans but ultimately unsuccessfully most recently in a case that went before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York, and the immediate client in that case were members of the Ku Klux Klan. The very good thing, factually, about that is the Klan in New York now is so controversial and so hated that without the mask of anonymity, those people would not have felt free to express their views.

Interestingly enough, the first time the Supreme Court defended, upheld the First Amendment right to anonymous speech, which is what we’re talking about here, a form of anonymity, pseudonymity was in a case involving a very different group with very different views on these issues, namely the NAACP in a case from the 1940s I believe, or 1950s when it was deeply dangerous to be identified as a member of this organization. You would be subject to at best possible job loss, at worst physical violence. So anonymity, including through mask wearing, is often essential for people to actually express controversial, unpopular points of view. That’s one side.

On the other hand though, if you are wearing a mask for purposes of concealing your identity and making it difficult, if not impossible for law enforcement to investigate and prosecute an act of violence, that is not justifiable. Think for example of masked, if we had had more masked protestors on Jan. 6 who would not be subject to prosecution for that reason. So I think to try to steer between those two through statutory language, I think is a very difficult exercise.

Oh, I’m sorry, do you … I mean I’m … OK. Anti-Zionism does not translate into anti-Semitism automatically. In some ways though, that is irrelevant because, as Erwin and I have both explained, and as the United States Supreme Court has repeatedly held, neither an anti-Semitic nor an anti-Zionist expression could be punished solely because of disapproval of its viewpoint.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Why don’t we take another question then we’ll take turns answering.

Nadine Strossen: Yeah, great.

Audience 2: Hi, thank you for speaking and it was a great experience. I’ve definitely learned a lot about free speech and as an up-and-coming law student myself, it was fun to learn that free speech is a lot more broad than I thought it was. But, well my question is regarding academic freedom. I’m a student myself, an undergrad, and I feel a lot of us do come here to Berkeley for that academic freedom. And I’ve had plenty of classes of opposing views to mine.

However, one thing I do disagree with is the academic freedom on campus I feel like does come into question and is violated sometimes when we do have speakers who table, like a group I know is Turning Point USA where it feels like the intent they’re coming here is not for an academic speech, but is to instigate conflict of other students. And as much as I’m open to discussions, I feel that instances where intent is the goal to instigate, to simplify, my question is if there is intent to get someone to dislike your opinion and instigate something out of them, are they allowed to be protected in freedom of speech?

Erwin Chemerinsky: Yes.

Audience 2: Mm-hmm.

Erwin Chemerinsky: Let me try to explain why. And I think this is a place where you and I would agree. People have the right to speak even if they’re being provocative. They have the right to speak even if their goal is to be provocative. And the difficulty of course is that sometimes speech we really like was done to instigate and to provoke. Your example with regard to the Civil Rights Movement, the way in which they engaged in demonstrations that we all applaud and admire was to instigate and provoke.

And I also worry about how are we going to know who was the speaker that was there to instigate and provoke versus some other motive we think more noble? Likely it’s some of both in most instances and in all likelihood, the speech we don’t like we call instigating and provoking, the speech we do like we’d say, “Well, that’s enlightening.” So the answer is even if the motive is just to instigate and provoke. Mylo Yiannopoulos, if people remember him, being the paradigm of that, it’s still protected by the First Amendment.

Nadine Strossen: And you have the right not to listen to it, too.

Audience 3: Yeah, sorry. I want to say I think that in the spirit of Mario Savio, students putting their bodies on the line and saying that the workings of the machinery is so odious and so makes you so sick at heart that you have to throw yourself on the gears. The protests have gone on over the last year around Palestine are precisely a case in point, in the same way that the students in the 1960s were looking at what was going on under Jim Crow oppression in the South, they felt like they had to do something dramatic.

That’s the same situation today around Palestine. It’s what’s needed and there’s great urgency, urgency for it. However, to say, Professor Chemerinsky, that there’s this great problem of anti-Semitism at a time when there’s great repression going on against the Palestinian protests, there’s a problem. Is anti-Semitism a scourge? Is it a problem? Yes. But the allegation of anti-Semitism is what’s being used to justify a massive clampdown on the pro-Palestinian, pre-Palestine movement.

That’s what’s going on in the real world. That’s how your words are being utilized is to justify the suppression of a new generation of protests at a time when people, at a time when people need to be fighting back and need to be taking disruptive action to the normal course of events. So how do you see that? And then I just want to say, in the spirit of Mario Savio, the disruptive protests against social outrages, outrages of this whole system that we live under, that protest needs to go on and we need to get to the root of the problem, the whole capitalist imperialist system and that’s what the revolutionary leader, Bob Avekian is talking about.

Erwin Chemerinsky: I think that was directed at me, so I should respond. I’ll say a couple of things. First, I think the first part of your question really goes to the concept of civil disobedience. If people want to violate the law or violate the rules to express a message, they then have to accept that there’s consequences and punishment for doing so. One of the unusual things over the last several years I’ve heard from students is when they want to violate the law of rules say “You can’t punish me because I’m being civilly disobedient.” That misunderstands civil disobedience. If students are going to violate the law, they face legal consequences. If they violate campus rules, they face campus consequences. And you may say it’s justified and it’s a good thing for them to do that, but the nature of civil disobedience is that one accepts the consequences.

As the latter part of your comment, I do not believe that condemning anti-Semitism is inconsistent with also condemning Islamophobia. I don’t believe that condemning anti-Semitism is inconsistent with even condemning what Israel is doing in Gaza. But I also think ignoring anti-Semitism is just wrong. The poster that was put up of me holding a bloody knife and fork with blood around my lips was anti-Semitic. The reason my house was targeted because I was a Jewish dean. If I wasn’t Jewish, they wouldn’t have come to my house. I have heard and seen more anti-Semitism in the last year than I have in my life, and I will not be quiet about that any more than we should be quiet about Islamophobia or racism or any other form of hate.

(Applause)

Audience 3: [Inaudible]

Nadine Strossen: I think the answer was complete. We need to go on somebody else in fairness.

Audience 4: I just want to say I thought this has been a terrific discussion and I think one of the things that’s come across is just how complicated it is. I mean, this is very, very difficult, but I think a result of how complicated it is, it’s very hard for people to know what can I do and what can’t I do? I think the administration’s done a good job at Berkeley of navigating these very turbulent waters and all, but at the same time, I think there are some challenges. I was lucky enough to be a student here during all the 1960s and was present at most of the events in the film. And as a result of the Free Speech Movement, I felt I was a great beneficiary, ’cause I was able to work with others to bring a lot of very important figures to campus, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and some that were very controversial, Stokely Carmichael and Senator John Tower of Texas who was a little bit to the right of Ted Cruz.