Bridging divides: from anger and mistrust to belonging — and hope

As UC Berkeley celebrates the 60th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement, it is emerging as a national leader in developing science-based practices that nurture constructive dialogue. The goal: Cool tensions, promote understanding and ease polarization.

Brittany Hosea-Small for the UC Berkeley Goldman School of Public Policy

September 23, 2024

Even before David Z. arrived at UC Berkeley, he had a strong, uneasy sense that he would not fit in. His family is conservative, and so is he. He’s not doctrinaire: He supports Donald Trump, but he believes in climate change, too. Even so, he suspected that at Berkeley, so famously progressive, he might be an outsider.

In class, or in meeting new people, he understood that one wrong opinion, one wrong observation made among the wrong people, could lead to lasting social penalties.

“The Young Republican club on campus was tabling on Sproul Plaza,” David recalled recently. “Obviously I’m interested, but there were people around. If they saw me going up to the table, what would they think of me? Those things go through your head. So I quickly went to the table and filled out the interest form. I was looking around to see if anyone there would recognize me. And then I quickly walked away.”

This fall, Berkeley marks the 60th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement and the political and social freedoms won by an earlier generation of activists. But a paradox hangs over the celebration: We have almost unlimited freedom to speak, yet many of us are struggling to have even basic conversations about deep disagreements over issues such as racial justice, the Israel-Gaza conflict and the presidential election.

As a result, people are retreating into the safety of their social silos. They’re frustrated and resentful, sometimes even afraid.

But just as Berkeley in the 1960s was at the vanguard in expanding free speech, today the campus community is striving for a new sort of change: to bridge these uneasy divides with programs, fellowships and classes to support healthy disagreement. As a result, the campus is emerging as a national center of innovation in nurturing dialogue to counteract the forces of polarization that are undermining democracy.

Keegan Houser/UC Berkeley

“We are committed to a constructive collision of ideas,” Berkeley Chancellor Rich Lyons said recently. “We’re committed to providing every community member a true sense of safety and belonging, regardless of who they are or what they believe in. We can fully enjoy the benefits that community provides if we can debate and disagree without descending into identity-based condemnation, without violence, harassment or discrimination, without infringing on the rights of others.”

On a recent evening, David attended a discussion at the Haas School of Business that explored the practice of “bridging” to ease divides and soothe mistrust. The presentation, organized by the Haas Office of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Justice & Belonging, kicked off a six-session certificate program attended by 80 students and alumni. It is part of a rapidly growing campus initiative that promotes the science and spirit of “constructive engagement” to help cool tensions and foster the sort of dialogue that universities are built to support.

Molly Robinson

But in our stressed-out moment, that sense of belonging is elusive and there’s much work to be done, said alum Julia McKeown, who leads the Campus Bridging Project at the Othering and Belonging Institute. Bridging can be especially challenging within institutions, including Berkeley, that have existing structures of inequity, McKeown said.

“Everything that is happening in the world means that you have folks wanting to break apart more, feeling very scared, turning inward and becoming smaller and smaller,” they said. “There is this deep yearning among the campus community to not feel so separate from each other, and also to not have to worry about hurting somebody else while trying to connect with them. That’s what bridging does. It addresses structural marginalization by providing spaces for people to speak freely and to hold each other’s humanity and shared interests.”

Berkeley as a national force for bridging and belonging

The concept of “bridging divides” draws some of its DNA from the sort of old-fashioned diplomacy that seeks to build connections and trust between opposing political parties or nations in conflict. But it’s updated with values and practices drawn from science and psychotherapy, and from religion and spirituality.

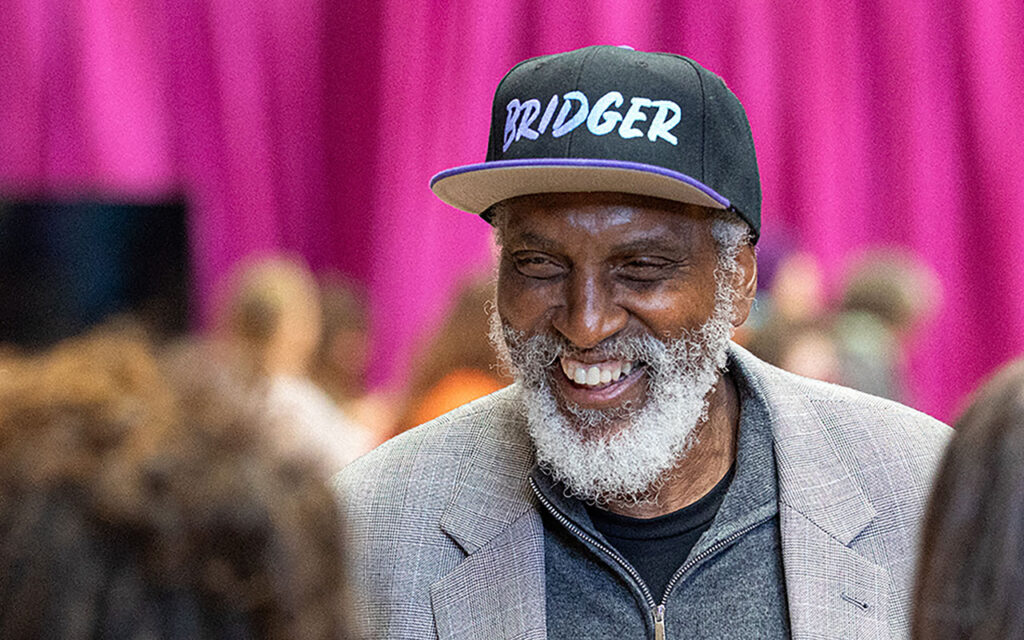

john a. powell, the influential UC Berkeley civil rights and legal scholar, began exploring the concept in 2015; two years later, after Donald Trump was elected president, powell began to intensively promote bridging.

Nicholas Lea Bruno/Othering and Belonging Institute

Today, the Othering and Belonging Institute that he founded offers a range of resources to support constructive dialogue. powell speaks frequently to high-level national and international audiences, promoting practices that nurture communities of belonging. His new book, The Power of Bridging: How We Build A World Where We All Belong, due out in December, offers a guide to reducing divisiveness and developing the skills needed for healthy disagreement.

University of Colorado, Boulder

On one level, the appeal of constructive dialogue is idealistic: It doesn’t aim to persuade, but instead to employ curiosity and deep listening to encourage understanding. At its best, it can ease the tension of chronic political and culture wars, said Juliana Tafur, director of the Bridging Differences program at UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center.

Since its founding in 2018, Bridging Differences has produced a playbook, featuring 14 science-based bridging skills, that has been downloaded more than 300,000 times. Its online course has enrolled more than 10,000 people. More than 200 higher education leaders nationwide have been trained in its learning fellowship.

Now, it is beginning to implement a statewide, multi-year initiative in Colorado to promote a sense of belonging in every community.

Tafur said her program operates in a social landscape torn by political and cultural conflict. But, she said, that’s not what most people want for themselves or the people they love.

Online forums are dominated by about 10% of the loudest and most extreme voices, she said. “But nearly three-quarters of Americans are absolutely exhausted. This group has been researched — they’re described as ‘the exhausted majority.’ They’re tired of the division, they’re tired of the polarization. They represent different sides of the spectrum, but they strongly believe that the state of division is outdated.

“So how do we expand our circle of concern? How do we move from the story of, ‘These are my people, and these are my goals,’ to a narrative that says, ‘Let’s create a shared story where everyone is included — your group and my group?’”

Joined by a growing corps of campus leaders and student activists, Othering and Belonging and Greater Good have made Berkeley a nationally influential center for constructive engagement. They’re active in global networks that span hundreds of political, educational and religious organizations.

Berkeley alumnus Manu Meel was one of the student co-founders of BridgeBerkeley, which grew out of the violent 2017 protests that erupted when right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos was invited to speak on campus. The organization eventually merged with groups in other states to become BridgeUSA, which is committed to diverse viewpoints, constructive discussion and solution-focused politics.

With Meel now serving as CEO, BridgeUSA has chapters at Berkeley and 64 other U.S. colleges and universities, plus 30 high schools. In the 2023-2024 academic year, it engaged more than 10,000 students. Meel speaks regularly to members of Congress, philanthropists and journalists.

“There’s a hypothesis,” Meel explained, “and we’re willing to go broke on it: The real divide in our generation right now is not between left and right, but between people that are open-minded and closed-minded. There’s a vocal, extreme element across the political spectrum, and everybody else is just scared.

“Our ultimate objective is not necessarily to bridge left and right. It’s to create the permission structure for dialogue to flourish.”

“There was so much vulnerability in that room, on both sides”

As a campus known for progressive politics and a history of sharp confrontation, it’s exceptional for Berkeley to become a national leader in easing tension and reducing conflict. But a question remains: How can Berkeley’s experts put their knowledge to work on their own campus?

A number of initiatives seek engagement in ongoing disputes that are highly sensitive and potentially volatile. This, the experts say, is where bridging work is the most ambitious — and the most difficult.

Consider the experience of Rena Lu, a senior in legal studies and an assistant in Othering and Belonging’s Campus Bridging Project. Last spring, she was part of an initiative called the Long Bridge Program to build connection and trust between graduate students and faculty after a bitter graduate student strike over pay and benefits that spanned 40 days in late 2022.

The Long Bridge Program, organized in collaboration with the Graduate Division, brought both groups together for two sessions last spring. Even months after the strike, emotions were intense.

“Sometimes people just want a space to be heard, where they feel like the other side can hear them, without any filters,” Lu said. “The work we did with graduate students and faculty was really remarkable — there was so much vulnerability in that room, on both sides.”

‘What you’re doing is stupid. You guys should not be on this campus anymore’

Or consider the experience of two student leaders of the BridgeUSA Berkeley chapter: Mira Rubio, the events coordinator, and Samantha Dalton, the president. Both are from families afflicted by political division and tension; Rubio is a liberal, while Dalton, uneasy with labels, is an independent.

Both agree that their work to reduce partisan polarization has, thus far, had only mixed success.

In tabling or other outreach, liberal students sometimes assume they’re closeted conservatives, Dalton recalled. “Some of them have walked up to our table [on Sproul Plaza] and said, ‘What you’re doing is stupid. It’s dumb. You guys should just quit and not be on this campus anymore.’”

Rubio said she’s had similar experiences. Organized campus Democrats have mostly spurned invitations to meet and talk.

“We’ve invited them to our debates,” she explained, “They’ve said, ‘We have issues we could be working on and petitions we could be passing out. Why should we debate? Are you doing this just to see people argue? Some kind of blood-sport?’”

And yet, Dalton, Rubio and their colleagues have slowly made progress. Some students — liberals, conservatives and independents — have welcomed the chance to reach across the divide.

“Without BridgeUSA,” Rubio said, “I don’t think any of the political clubs would be going out of their way to interact with one another at all.”

Israel and Palestine: “The aim is … to work together for a common humanity”

After conflict erupted between Hamas and Israel almost a year ago, a great deal of tension and animus arose on campus between students, faculty and staff — and the tensions persist this semester.

Early attempts to create campus dialogue and understanding across the divide found little traction. Now, however, a carefully structured initiative is bringing about 15 students together for deep discussion about Israel and Palestine. The fellowship summary describes the process as “radical and hopeful,” an experiment undertaken “in the spirit of transformative dialogue.”

“The aim is to foster dialogue across the gaping differences — cultural, political, personal, religious — and still to be able to see each as sisters and brothers.”

Asad Q. Ahmed

The Berkeley Bridging Fellowship is a collaboration of the Center for Middle East Studies, directed by Asad Q. Ahmed, and the Center for Jewish Studies, directed by Ethan Katz. The Greater Good Science Center has signed on as a partner in support of fellowship.

The initiative is so sensitive that Katz and Ahmed have sought to keep it insulated from outside pressure. But when pro-Palestine advocacy groups this summer accused the fellowship of normalizing genocide, the two professors wrote an exchange for publication in the Daily Californian student newspaper.

While acknowledging their own deep differences over the conflict, they pledged to lead a process that is both critical and compassionate.

“We do not intend to sweep over difficult parts of history,” Ahmed wrote. “The aim is to foster dialogue across the gaping differences — cultural, political, personal, religious — and still to be able to see each as sisters and brothers and to work together for a common humanity.”

Added Katz: “We had many more strong applications than we could accommodate. We felt that there is a real thirst for this kind of discussion from across our student body, and we were reminded that Berkeley is home to students of extraordinary talents and capacity — as thinkers and as humans.”

Abandon persuasion, abandon winning — instead, try to understand

Other campus initiatives have a different objective: to train a generation of future bridgers with the skills needed to transform conflict into understanding.

Jeffrey Watts, American University

Former UC President Janet Napolitano, now director of the Center for Security in Politics at Berkeley, has helped to lead the Uncommon Table initiative to bring students together with politically and geographically diverse groups for a meal and deep discussion.

At Berkeley Law, the Judicial Institute offers a free virtual class, Effective Communication Across Differences, to law students across much of the nation. And the ethnic studies department and Othering and Belonging’s Campus Bridging Project are offering a supervised group study class, Bridging and Belonging.

On the first Wednesday of the fall semester, assistant professor Erika Weissinger convened her new class, Constructive Dialogue in Public Policy, the centerpiece of an ambitious new program at the Goldman School of Public Policy.

We’re all interconnected. Hate, atomization and polarization hurt me personally, even if the hatred is not directed at me.

Erika Weissinger

The class convenes graduate students to focus on the basics of disagreement and constructive dialogue, and the practices that can encourage trust: curiosity, deep listening, focusing on common ground rather than differences, telling stories rather than asserting opinions. Abandon persuasion, abandon winning — instead, try to understand.

“Americans have experienced those debates online that went nowhere, that were hurtful,” Weissinger said later. “After January 6th, and thinking about the upcoming election, there’s genuine fear. Some of that is validated by the polling that we’re seeing about Americans’ support for political violence.”

“We have to be able to sit down and say, ‘I’m committed to talking this out’”

One of Weissinger’s students, John “Chip” Moore, already has ample experience with bridging divides in politics and policy.

Photo courtesy of Goldman School of Public Policy

In Oakland, he was a pioneering cannabis entrepreneur working with city officials on permits that would legitimize his business. His political skill earned him a reputation, and he was recruited to serve on the Police Accountability Board and then the Planning Commission in Berkeley, his hometown. Most recently, he chaired the Berkeley Unified School District Reparations Task Force that recommended a package of reparations for Berkeleyans who are descendants of slaves.

At the start, the reparations panel was deeply divided, but Moore is proud that it ended in unanimity. Such experience has given him firsthand insight into how to make connections in a complex, highly emotional disagreement.

“You have to find where you can build some consensus out of each other’s talking points,” he said. “You start the conversation there. …You have to ask: Do we make sure there’s guardrails? Do we want to keep it safe? Is safe a good thing?

“These are all hard conversations. But we have to be able to sit down and say, ‘I’m committed to talking this out.’”

“Even in war, there comes a time when people need to talk”

Dan Jung

The practices of constructive engagement are shaped by the sort of psychotherapy used for families in crisis, and by spiritual disciplines, as well. Weissinger is not a Buddhist, but her views are shaped by Buddhist values.

“We’re all interconnected,” she explained. “Hate, atomization and polarization hurt me personally, even if the hatred is not directed at me. Embracing the idea that we are all interconnected challenges the narrative of ‘us versus them’ and encourages a more compassionate, inclusive approach to dialogue, where understanding and empathy become the foundation of our interactions.”

Even with the best intentions, though, bridging divisions and constructive engagement sometimes don’t work, the experts said. If parties in conflict are acting in hate, or with aggression, they added, it’s best to walk away.

And yet, powell seemed reluctant to walk away from almost any conflict.

“Even in war,” powell said, “there comes a time when people need to talk. Unless it’s a question of complete domination, or mass genocide, you’re going to have to talk to people. That’s the practical level. But there’s a deeper level as well, a spiritual level.”

In powell’s view, we face challenges similar to those faced by Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Nelson Mandela, all 20th century icons of civil rights and human liberation. And, he said, we can embrace the compassion at the core of their work.

“They’re inspirations for the idea that we don’t need perfect conditions” to make progress, powell said. “We talk about people who are cult followers of Donald Trump, but a lot of his supporters are probably in a softer position.

“What’s driving them? I think, by and large, it’s a fear of not being seen, and not belonging. People say they feel disrespected. Well, respect them. We should talk to people who are in that exhausted middle. We need to understand them — not what their position is on abortion, not what their position is on immigration, but their deep, heartfelt fears and aspirations for the country, for their family, for their community.

“In that understanding, the possibilities of bridging are much, much greater.”