With the help of AI, UC Berkeley researchers confirm Hollywood is getting more diverse

A new study used facial recognition technology to track the amount of time actors appear on screen in more than 2,300 films.

Chris Pizzello/AP

November 4, 2024

With recent box office hits like Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, The Little Mermaid and Everything Everywhere All at Once, the average viewer might assume that the casts of Hollywood films are more diverse now than they were 10 or 20 years ago. But verifying these perceptions can be tricky.

Even before the #OscarsSoWhite social media campaign in 2015 brought much-needed attention to the lack of diversity in Academy-nominated films, film scholars had begun documenting the lack of representation of women and actors of color in Hollywood. Doing so requires that they watch hundreds of hours of film and take meticulous notes on each actor’s performance, including if the actor was cast in a leading role and has significant dialogue, and how often the individual appears on screen.

Now, a team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, is using computer vision to dramatically speed up this process. By subjecting movies to the “silicon gaze,” they hope to make it possible for scholars to analyze a broader array of films — and ask more detailed questions about representation — than ever before.

“I see this work as complementary to human viewing. I think that if you have the capacity to go watch hundreds of movies as other studies have done, you should do that, because those methods are likely going to be more accurate,” said David Bamman, an associate professor in UC Berkeley’s School of Information. “But automation can give us access to measurement at a much larger scale. We can apply validated computer vision methods to a much larger collection of films than we could possibly watch, and at a finer granularity than we could measure by hand.”

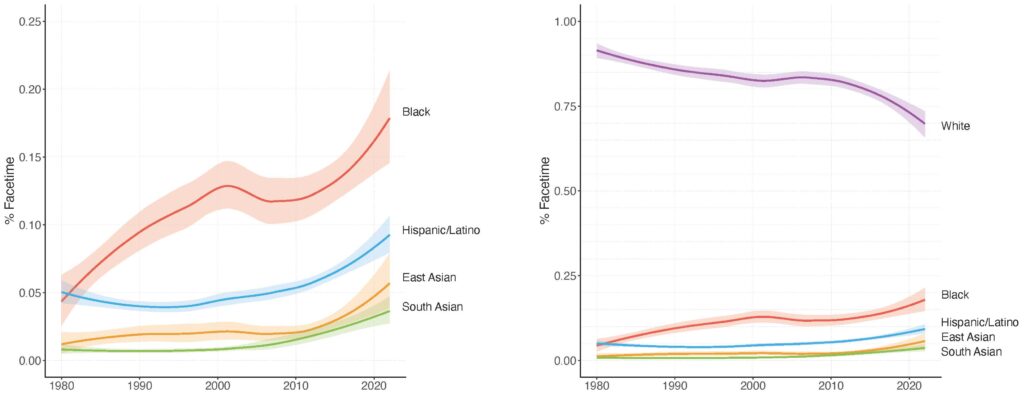

In a new study appearing this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Bamman and his team used facial recognition technology to track the amount of time actors appear on screen in more than 2,300 Hollywood films released between 1980 and 2022 — a total of 4,412 hours of footage. They analyzed both “popular” films, defined as the top 50 box office earners each year, and “prestige” films, which are films nominated for “Best Picture” by at least one of six different organizations, including the Academy Awards and the Golden Globes.

The study confirmed that, since 2010, Hollywood films have indeed been getting more diverse, with increasing representation for actors who are women, Black, Hispanic/Latino, East Asian and South Asian. Not only is Hollywood as a whole more diverse, but the casts of individual films are also becoming more diverse, meaning that change is not solely due to a small number of movies featuring all non-white casts, such as Black Panther.

“If you were to pick any single movie that’s being made right now and just watch that one movie, on average you’re going to see greater diversity within it than within a movie that was made 10 years ago. However, we also find that there is still greater diversity in non-leading roles than there is within the leading ones,” Bamman said. “This highlights one of the advantages of our approach. A lot of work that’s looked at representation for race and gender using manual methods has focused, by necessity, on the leading actors, but we see here that there is a lot more diversity as you go further down the cast list.”

Breaking the digital locks

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

The automated methods Bamman and his team used are possible now because of a new federal regulation that eased “digital locks” on DVDs.

Since the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act was passed in 1998, copyright protections have strictly prohibited researchers from breaking the digital locks on DVDs that prevent a DVD from being pirated and protect the copyright holder’s rights. With these technological protections in place, it is very difficult to subject the films to new computer vision technologies that can recognize and track the appearance of faces or objects in video.

However, inspired by a training institute on how the law shapes computational research that was organized by co-author Rachael Samberg, director of scholarly communication and information policy at the UC Berkeley Library, UC Berkeley’s Samuelson Law, Technology and Policy Clinic and Author’s Alliance petitioned the U.S. Copyright Office to allow higher education institutions to decrypt these locks on DVDs and on e-books in order to carry out large-scale data mining for scholarly research and teaching. With the help of testimony in 2021 from Bamman, the office passed the exemption and renewed it in 2024.

“The work we’ve done across multiple units and departments at UC Berkeley helped show the Copyright Office that this exemption is critical for advancing modern research practices reliant on computational analysis,” said Samberg. “For the first time, U.S. scholars are now able to carry out this kind of research at scale on TV shows and films.”

While researchers can now bypass technological protections to study copyrighted movies and books, there are still strict rules about how the data can be used and shared. First, any institution that would like to carry out such analyses must own the material — meaning that Bamman and his team had to buy their own copies of all 2,307 films that they studied.

The analysis also must use measures to keep the data secure. Bamman credits UC Berkeley’s Secure Research Data and Compute (SDRC) platform, a campus cluster that is specifically designed for handling secure, highly sensitive data, for making the research possible.

“If we didn’t have the SRDC at Berkeley, support from the Mellon Foundation and legal expertise in the Library and Samuelson Clinic, we couldn’t have carried out this study,” Bamman said.

Tracking large-scale trends

Courtesy of David Bamman

For this first computer vision study, Bamman decided to focus on diversity, in part because of the strong history of film scholarship in this area.

“As we are developing computational methods to measure diversity in a larger collection of movies than people have been able to look at before, we wanted be able to compare our results with what I see as gold standard work — studies that have been measuring these same issues of representation over the past 20 years through manual viewing,” Bamman said. “We also know from the #OscarsSoWhite movement in 2015 and 2016 that there is a significant lack of racial diversity in Oscar nominations at the actor and director level.”

While the study used computer vision to track actors’ appearances on screen, algorithms were not used to make judgements about race, gender or ethnicity, Bamman said. Instead, his team consulted Wikidata for public understanding about each actor’s gender, and conducted user surveys to determine how viewers might perceive each actor’s race/ethnicity.

“The rationale for thinking about perceptions is that we want to try to approximate the representation that an average viewer sees on screen, and not try to infer anything about the identities of actors, which is unknowable outside of statements by the actors themselves,” Bamman said. “Focusing on perceptions gives us a sense about how representation in casting decisions and screen time ultimately lands in viewers.”

John Bauld via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

In addition to confirming that Hollywood films have become more diverse since 2010, the study found that the rate at which viewers see women on screen increased from a steady 25% between 1980 to 2010 to around 40% in 2022. However, all groups except white men remain underrepresented in leading roles compared to non-leading roles.

They also found that Black actors are underrepresented in award-nominated films, compared to popular films, but that this difference is largely due to underrepresentation in award-nominated films from 1980 to 2010.

To support research reproducibility and encourage further understanding of the films, Bamman and his team have released non-copyrighted elements of their data, including metadata about the frames in a movie that each actor appears in, the location of each face within each frame and the UPCs (Universal Product Codes) of all the DVDs they purchased.

In the future, Bamman said he also hopes to use the data set to ask more nuanced questions about representation in film — not just examining the presence of an actor on screen, but also how the person is depicted and how these depictions may relate to stereotypes and biases.

“I’m hoping that this is really able to accelerate research in the cultural analytics of film, where we and others are able to use methods from computer vision to measure large-scale trends in these important objects of culture,” Bamman said. “We would love to work both with movie studios and film researchers toward this goal.”

Additional co-authors of the study include Naitian Zhou of UC Berkeley and Richard Jean So of McGill University. The research was supported by funding from the Mellon Foundation.