How World War I helps explain what gave rise to Trump’s second term

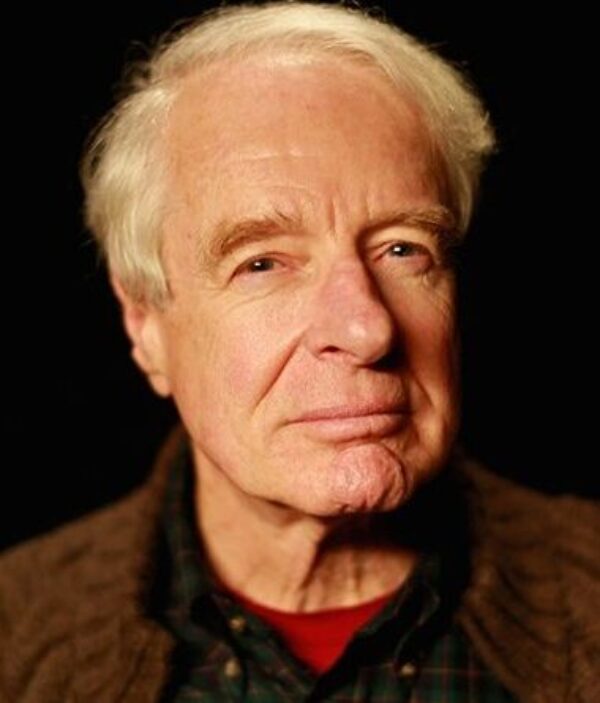

UC Berkeley historian and journalist Adam Hochschild discusses how today’s politics have precedent in the anti-immigrant sentiment and authoritarianism during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency.

Library of Congress

November 13, 2024

In the days since former President Donald Trump’s election victory, many of his critics have sought understanding by looking to fascism’s ascendance in 1930s Europe. They need not look overseas, says Adam Hochschild, a historian and a lecturer at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism.

In his 2022 book, American Midnight, Hochschild chronicled the oft-forgotten period of U.S. history between World War I and the Roaring ’20s. It was a time marked by widespread anti-immigrant sentiment and mass deportations. President Woodrow Wilson’s administration effectively shut down news publications it disagreed with. Federal authorities jailed labor organizers. Vigilantes threatened and even killed political dissenters.

UC Berkeley News recently asked Hochschild about what gave rise to this period that threatened American democracy and how it fits within a long history of anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S. He also shared how historical figures who fought for justice and human rights give him hope, and how now, as ever, history can be a helpful guide forward.

UC Berkeley News: Your book was published in 2022 and implicitly suggests many stark comparisons between the first Trump administration and the era 100 years earlier. With Trump about to return to the White House, how are you thinking of the historical parallels?

Adam Hochschild: There are many ways today feels eerily similar to the Red Scare period of 1917 to 1921. Several major candidates for both the Republican and Democratic nominations for president in 1920 campaigned on platforms promising mass deportation. Other politicians thundered about immigrants polluting the purity of American blood.

And in his second term, Woodrow Wilson’s administration, both before and after Wilson was disabled by a stroke, did things that Trump would like to do. Under the sweeping provisions of the Espionage Act, passed by a compliant Congress, it closed down some 75 newspapers and magazines and put hundreds of Americans in jail solely for things they wrote or said.

Harris & Ewing/Library of Congress

Media and propaganda played a major role in shaping public opinion, especially anti-immigrant sentiment, during and after World War I. How do you think the media’s role in influencing today’s political discourse compares to that era?

Despite the dramatic, disturbing shrinkage in local news coverage, I think Americans are better served today by the best of our media than they were a century ago.

I think Americans are better served today by the best of our media than they were a century ago.

Adam Hochschild

Back then, all too few newspapers and magazines engaged in serious investigative reporting, and far too many bowed to the mood of patriotic fervor and anti-radical frenzy that accompanied the First World War and the Red Scare that overlapped and followed it.

Today, only the BBC, perhaps, rivals The New York Times as a news organization that is respected and followed throughout the world. And today’s nonprofit news organizations, like ProPublica, do excellent work, as well. There’s a vast universe of vituperation and lies in the media world and social media, as well, of course, but as an obsessive reader of news, I’d rather be in the United States than anywhere else.

The book also chronicles those who resisted oppression under Wilson and fought for freedom. What lessons from history do you think are helpful to people concerned about a second Trump term?

I think we can always be inspired by those who stick to their beliefs, even when public opinion and government repression make it difficult or dangerous.

The First World War remade the world for the worse in every conceivable way — and laid the groundwork for a second, even more deadly war. I admire the Americans who were brave enough to speak out against it at the time. Sen. Robert La Follette saw himself shunned by his fellow senators and burned in effigy at his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin. Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs was sent to prison. Conscientious objectors were treated so badly in military custody in 1917 and 1918 that some of them died. I don’t know what challenges will face us in the years ahead, but we will need people as brave as them.

The nativism of this era led to the 1924 Immigration Act. How similar were the fears and political forces that propelled that anti-immigrant movement compared to today’s?

Nativism has a long and nasty history in the United States. In the 1850s, there were riots attacking Catholic immigrants from Ireland. In the 1880s, we passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, and 28 Chinese coal miners were massacred in Wyoming.

Nostalgia has long had significant appeal for demagogues.

Adam Hochschild

In 1902, a young college professor bemoaned the way “men of the sturdy stocks of northern Europe” were being overwhelmed by “men of the lowest class from the south of Italy and men of the meaner sort out of Hungary and Poland” [i.e., Catholics and Jews]. Ten years later, that writer was elected president — Woodrow Wilson.

Immigrants have long been a convenient target for anyone who finds the country changing in ways they don’t like. But this country is constantly changing, and wave upon wave of immigration has helped make us all that we are.

For the past eight years, the “Make America Great Again” movement has traded in a reductive nostalgia for what Trump frames as a bygone golden era. As a historian, where does this nostalgic appeal come from? How does it compare to similar sentiments in other historical periods?

Nostalgia has long had significant appeal for demagogues. The great Polish writer Ryszard Kapuściński has a wonderful phrase for it, “the myth of the Great Yesterday.” You can see that nostalgia being wielded by Donald Trump, by Vladimir Putin, evoking the superpower status of the old Soviet Union, and by Adolf Hitler, recalling the glory of the German Empire before it was defeated and shrunken by the First World War.

Trump has wielded this nostalgia so effectively because the core of his supporters are blue-collar white men without college degrees whose real income has been flat or declined in recent decades. Yesterday might not have been so great for all of them, but they feel that today is worse — and it’s that feeling that he speaks to.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.