How to think about Thanksgiving like a food historian

UC Berkeley’s Rebecca McLennan explains the backstory of the bounty on your table.

Marjorie Collins/Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives

November 26, 2024

Thanksgiving is a holiday all about food — and gratitude, of course — that creates sensory memories: rosemary-scented stuffing, a well of warm gravy threatening to spill out of its mashed potato seat, tart goops of cranberry sauce, triangles of pie and a massive bird at the center of it all.

But while we often know the short-term backstory of what’s on the table (“This cornbread is my aunt’s recipe” or “We started making this side when so-and-so became vegetarian”), the larger historical context behind what many consider the traditional Thanksgiving spread may be less top-of-mind.

And surprisingly different.

For instance, eels and shellfish were part of the typical diet of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, the Indigenous people in what is now the Northeast coastal region of the U.S. And, according to Smithsonian magazine, early gratitude festivities likely would have lacked pies (butter was scarce for pie crust) and both sweet and regular potatoes.

A history, not just of people, but of the planet, is on your plate!

Rebecca McLennan

As part of her scholarship, Rebecca McLennan, a UC Berkeley professor of history, has given deeper thought to what’s on ourThanksgiving plates today. McLennan’s research mainly focuses on the history of capitalism, the law and the environment in North America, but she’s also taught courses on food history and “foodways,” the study of the relationships between food and those who consume it.

The concept stretches far beyond cooking and eating, McLennan says; it also includes food production, food waste, our beliefs and rituals around food, and even what edible things a culture might consider “food.”

With Thanksgiving approaching this week, Berkeley News asked McLennan about the history of what we eat every November and how Americans’ relationship with their food has changed over the years we’ve been celebrating Thanksgiving.

UC Berkeley News: What is something that average folks who haven’t studied food history might not be thinking about when they eat?

Rebecca McLennan: The food on your plate is a thoroughly historical artifact; each ingredient, each dish, the particular combination of dishes, the fork or chopsticks you’re using, the vessels on which your food is nestled, the setting for your meal: All of these were made possible by a complex set of relationships between people and culture and the world around them at different points in time. The history of your meal is a story of dramatic change, both among people and between people and the material world — the earth, oceans and ecosystems. A history, not just of people, but of the planet, is on your plate!

Elizabeth Alfcamp/Library of Congress

In pre-industrial times — certainly before about 1800 — Americans, and the vast majority of humanity, knew where their food was raised or hunted, how it was preserved, and even by whom it was raised or foraged. Food sources were not entirely local before 1800. Famously, the spices that affluent people consumed and the salt cod that Europeans devoured by the barrel traveled thousands of miles around the world and passed through many hands and marketplaces. But most people’s daily sustenance was grown or slaughtered or fished no more than a few dozen miles from home, even in the case of urban areas like New York City — and the remains of their food were returned home, too, in the form of nutrient-rich manure, with which farmers fertilized the fields and helped to renew the growing cycle.

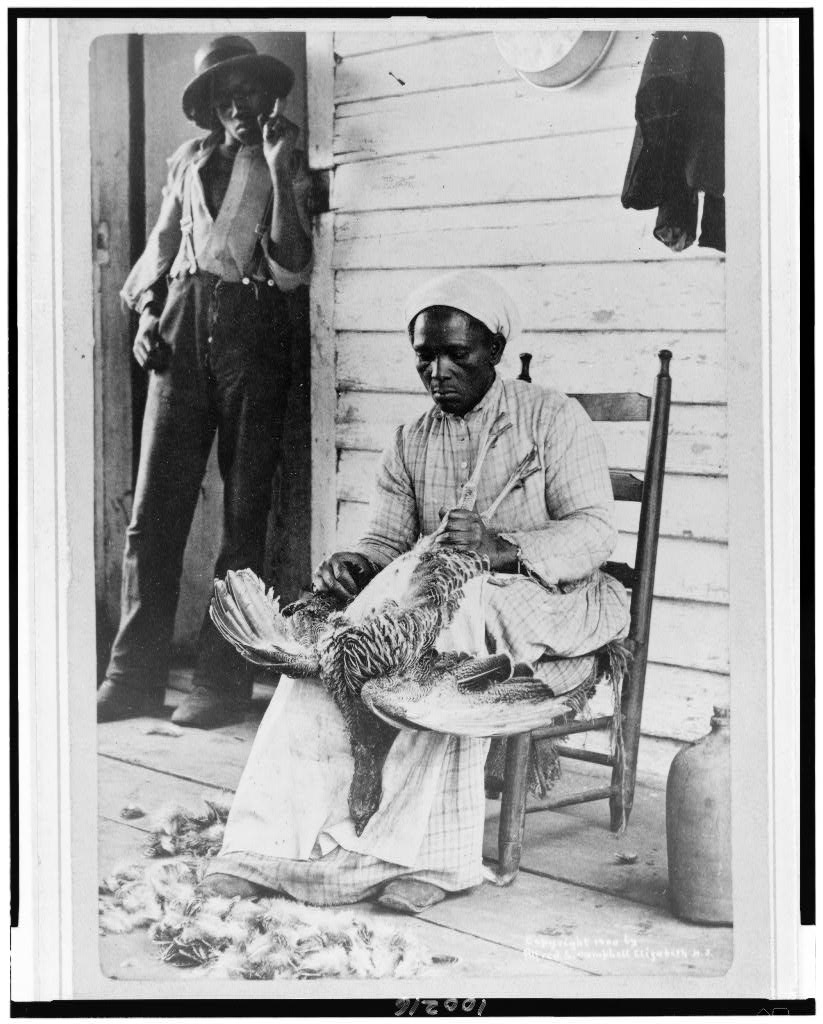

Today, thanks to the industrialization of agriculture and the advent of big cities and global markets, the overwhelming majority of industrialized countries’ food is produced at scale, hundreds if not thousands of miles away from where people consume it; food production and the people who pick or plant or slaughter it have become anonymous. Most people in places like the U.S. consume a much greater variety of foods, but know next to nothing about where and when their food originated, how it was processed, or who raised or handled it. And whereas 19th century Americans were deeply suspicious of this anonymization of their food systems, today most people are either not that curious about the geographical and social origins of their food, much of it picked by low-wage migrant workers, or else they’re actually excited to eat foods that are not grown locally.

B.W. Kilburn/Library of Congre

I myself love New Zealand–grown kiwis and a good, tangy Taleggio cheese from Lombardy. The local, age-old cycles of production-consumption-fertilization have mostly been replaced by global patterns of labor, except of course in a handful of enlightened municipalities, like those in the Bay Area, that plow household compost back into city parks and gardens! No part of my delicious kiwis, or really any of the foods we eat, are making it back to where they came from.

When did Thanksgiving as we know it emerge?

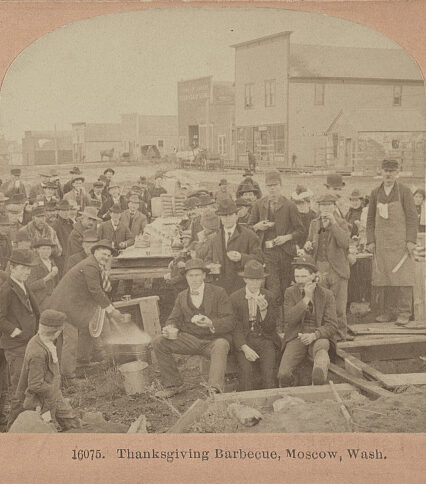

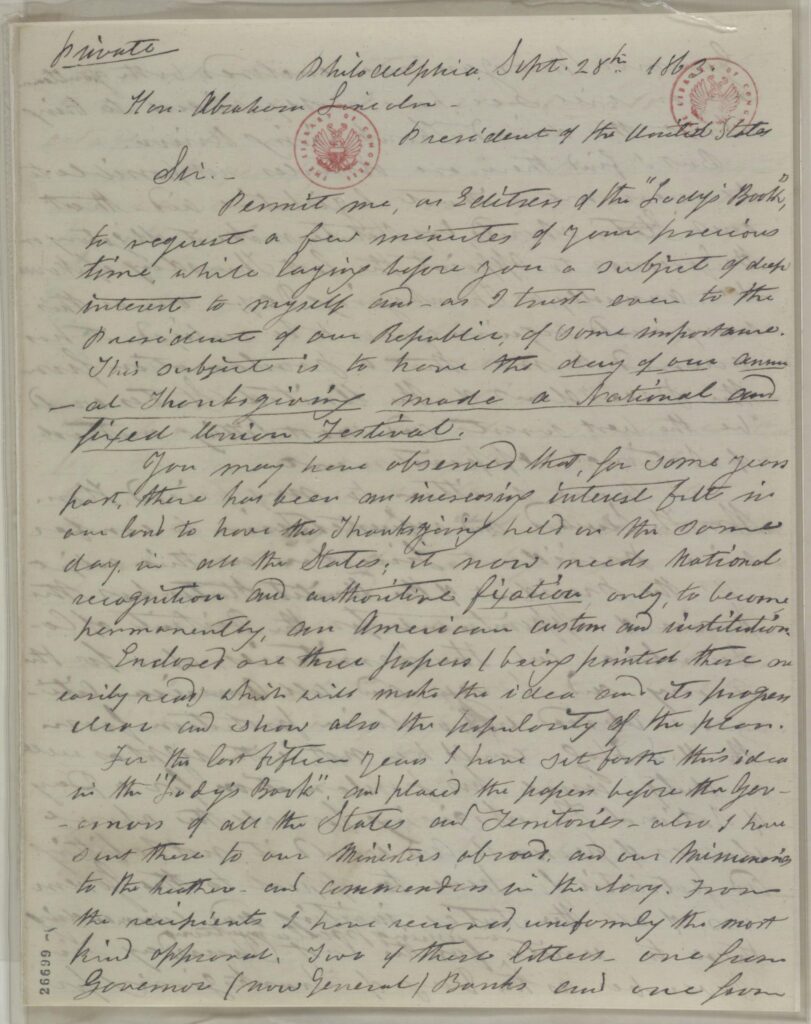

The Thanksgiving celebration itself originated not in Plimoth Plantation, but among middle- class and affluent people in pre-Civil War New England. Typically, it involved church in the morning, followed by some wild turkey shooting, among the men and boys, and a turkey feast prepared at home by mothers and daughters, or servants. In the 1840s, Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor and writer, lobbied state governors and anyone who would listen to make the “Great American Festival” a national holiday, believing that a national Thanksgiving could unite the nation and avert a looming civil war. She wasn’t that successful on either count: On the eve of the Civil War, Thanksgiving was only observed in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic states — and Texas!

Library of Congres

Lincoln declared Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863 — great news for soldiers and families, but bad news for turkeys: By then, turkey had become the center of the festive meal, and the new federal holiday boosted turkey consumption.

From a food history perspective, what don’t we know about the bird that’s the centerpiece of the Thanksgiving table?

One of the more curious things about turkey’s prominence is that the domesticated turkey that 19th century Americans often served at Thanksgiving was actually an imported species. Indigenous peoples of Mexico had domesticated turkeys over 2,200 years ago. Although local wild turkey — chewy and gamey — was often served at Thanksgiving tables, many Americans served the more succulent meat of domesticated turkeys, the ancestors of which had been brought back to Europe by the conquistadors after 1519. New England settlers then carried the European descendants of these domesticated Mexican turkeys back to the Americas.

Carl Hassmann/Library of Congress

Serving a whole turkey for Thanksgiving Day remained quite expensive through the end of the 19th century, well beyond the means of most immigrant and other working class Americans. But employers and political bosses, by 1900, routinely distributed whole birds to workers’ and constituents’ families, and by the 1920s, turkey on the Thanksgiving table was becoming the norm.

The U.S. is now the world’s largest turkey producer, and it’s also the producer of the world’s largest turkeys. Through breeding programs, the details of which readers might find disturbing, the average weight of a turkey has almost doubled, from 17 pounds in 1960 to around 30 pounds today. Peter Singer, the famous animal rights philosopher, has written an entire book on the industry, Consider the Turkey.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Hungry for more Berkeley-related food history content? The Bancroft Library has a rare copy of a 1796 cookbook that is the earliest known cookbook written by an American, and its staff baked a “pompkin pie” recipe from it, along with two other historical pie recipes. Read about it here.