No. 1 book of the century, ‘My Brilliant Friend’, is subject of UC Berkeley research, courses

Three instructors discuss why Italian author Elena Ferrante’s work is so captivating worldwide, including at Berkeley.

HBO

December 16, 2024

My Brilliant Friend, by the pseudonymous Italian author Elena Ferrante, is the New York Times’ No. 1 book of the century. This recognition, and the recent adaptation of Ferrante’s four-novel Neopolitan Quartet into an HBO series, underscores this writer’s profound influence.

Ferrante’s popular novels, translated into English by Ann Goldstein, are an intimate exploration of friendship, motherhood, identity and societal structures in mid-20th century, postwar Naples. They’ve also inspired research and courses at UC Berkeley by Annamaria Bellezza, a distinguished senior lecturer in Italian studies; Mario Telò, professor of ancient Greek and Roman studies, rhetoric and comparative literature; and Rhiannon Welch, the Giovanni and Ruth Elizabeth Cechetti Chair of Italian Literature.

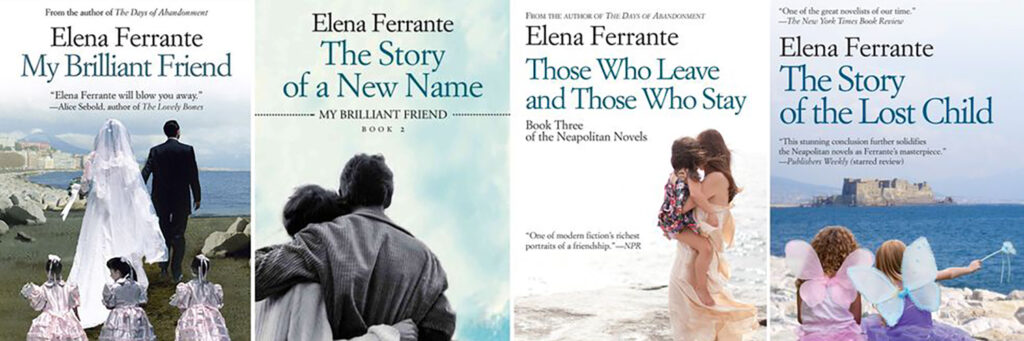

The Neapolitan Quartet — My Brilliant Friend (2012), The Story of a New Name (2013), Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014) and The Story of the Lost Daughter (2015) — is a fiction series that traces the intertwined lives of Elena (Lenù) Greco and Raffaella (Lila) Cerullo, born in 1944 in a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Naples. The novels span 60 years of their lives and explore their enduring, yet often tumultuous friendship as they navigate their violent, patriarchal and stifling social environment.

For Berkeley News, Sarah Fullerton from the College of Letters and Science’s Division of Arts and Humanities recently interviewed these instructors to learn more about Ferrante’s work through the lenses of language, theory and film.

The interviews were conducted via email and edited for length.

Sarah Fullerton: What fascinates you about Ferrante’s work or inspires any research and teaching you do?

Jen Siska for UC Berkeley

Annamaria Bellezza: I have taught Elena Ferrante in upper division courses in Italian over the last three years in a variety of combinations and contexts. Past courses include Elena Ferrante: An International Literary Sensation, From Page to Screen: Italian Master Storytellers, and Bold Voices of Italy: Power, Sexuality, and Storytelling. My experience teaching female authors of Southern Italy with an emphasis on Ferrante has been extraordinary. It has been a literary journey like no other because of the way students engage with and relate to the universal nature of the themes in Ferrante’s work — identity, friendship, love, class struggle, gender roles, ambition, the tension between loyalty and rivalry, admiration and envy, and the search for personal fulfillment.

Although deeply rooted in Italian culture and history, Ferrante’s novels resonate with students due to their exploration of emotions and relationships that transcend cultural boundaries, allowing readers to see their own inner conflicts reflected in the characters’ journeys.

Mario Teló: I have just finished an essay on the maternal drive and the myth of Helen and Leda in The Lost Daughter (a 2006 novel by Ferrante). There is a complexity to Ferrante’s writing that makes her comparable, in depth of thought, to the likes of Melanie Klein and Julia Kristeva. In Ferrante’s novel, the mother-daughter relationship takes the shape of aggression and guilt, an aggressive sense of guilt, or more precisely, an aggressive response to the perennial sense of guilt, self-doubt and self-loathing that comes with motherhood, as such. Maternal anxiety is conceived as the ongoing, repetitious, never-satisfied testing for the empirical presence of a child whose ontology has already been internalized as an irremediable absence — cognitively, psychically and emotionally.

Jen Siska for UC Berkeley

Rhiannon Welch: I’m fascinated by how such an erudite and learned text has also been so popular; so often we mistakenly believe that complexity and sophistication make a work inaccessible, but Ferrante’s works join a long literary tradition that showcases how this isn’t the case. I’m skeptical of some of the ways we designate “great works” of literature, but I have to say this might be one of the most convincing to me. Toni Morrison put it this way when she described what she wanted for her own work, namely that it “be as demanding and sophisticated as I want it to be, and at the same time be accessible in a sort of emotional way to lots of people.” Maybe something similar is happening with the Ferrante phenomenon.

What themes are woven through My Brilliant Friend and the Neapolitan Quartet, and why do they resonate so deeply with readers in the 21st century, especially students?

Bellezza: As Ferrante delves into socio-political changes in postwar Italy, she highlights issues of economic and educational inequality, themes which remain strikingly relevant in the 21st century as societies worldwide grapple with economic disparity, shifting gender norms and the desire for autonomy and self-realization. The focus on intimate, personal narratives within broader societal changes creates a connection between the individual and the collective, making her work relatable to people across diverse cultural and geographic backgrounds.

What I found that particularly draws students to Ferrante’s world is that it touches aspects of the human experience with unflinching honesty. Ferrante’s writing is raw and uncensored, especially when it comes to the female experience. Women are given permission to be bad, to be violent, to curse, to have sexual desires and describe these primal feelings in detail with no shame or guilt, to fall apart, to become undone … in a way that no other male writer has ever dared to do.

Jen Siska for UC Berkeley

Students identify with Ferrante’s unfiltered portrayal of life’s messiness, ambiguity, ambivalence and the struggle to define oneself within larger societal forces.

Students in my classes with family ties to different parts of the world were fascinated by Ferrante’s depiction of the city of Naples and the “rione” (the working class neighborhood where the story takes place) as a living character, a powerful entity that consumes its dwellers, a force to be reckoned with, “the gravitational pull of the birthplace” (that prevents Lila from crossing over and draws Lenù back to her origins). Naples became Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, Philadelphia, Addis Ababa, Quito, Paris. These students’ connections to Ferrante’s world were revealing and illuminating of our shared human experience.

Telò: I think that what resonates so strongly with contemporary readers is Ferrante’s bold choice of representing the intrinsic ambivalence of friendship — and, in particular, female friendship. Friendship is always layered with “ugly” feelings — competition, envy, jealousy, forms of implicit hostility. Is it possible to be friends without at the same time being (always) frenemies? The intensity of friendship inevitably results in ambivalent feelings — in a rawness that cannot be controlled. Who has the courage to problematize the inevitably idealized and sentimental picture of friendship? I think that Ferrante is quite unique in this respect.

Ferrante’s work has gained international acclaim, despite its deep ties to Italian culture and history. What makes her stories so universally relatable?

Bellezza: The themes of friendship, ambition and societal pressure reflect the lived experiences of young readers navigating their place in the world. Ferrante’s unflinching exploration of gender roles, class divisions and personal struggles also provides rich material for academic analysis, making her novels an ideal fit for courses exploring literature, language, gender studies or cultural criticism. For the students I had in my classes over the past three years, Ferrante’s work opened up an entire new way of perceiving, reflecting, experiencing, and provided them with a mirror and a lens to understand both themselves and society. And … students discovered a newly found passion for reading. Ferrante’s work truly touched them. Ultimately, this is what great storytellers do: they touch, they inspire.

Welch: Part of what’s so compelling about Ferrante’s work, and the Neopolitan Novels, in particular, is her detailed anatomy of a friendship between girls (and women) in conditions of profound constraint and violent oppression within the home as without — a totalizing atmosphere — and how these same girls (and women) seek a way through or out with creative expression, that is, by reading and writing.

She draws readers in with her rigorous attention to the particularities of everyday life in a grocery store or the seasoning room of a sausage factory. But the conditions she describes, and the relentlessness of Lila and Lenù’s conflicted desires to pierce through their suffocating constraint, with moments of liberation followed by an almost magnetic, irresistible pull back into the rione, extend beyond the particularity of place that’s so characteristic of her work.

I love how Ferrante herself describes the task of a writer [in an essay translated by Ann Goldstein for The Guardian], and I think it gets at an answer to this question about the eloquent balance in her novels between the particular and the universal: “An individual talent acts like a fishing net that captures daily experiences, holds them together imaginatively, and connects them to fundamental questions about the human condition.”

Jen Siska for UC Berkeley

Telò: It is … the psychological complexity of her female characters. Yes, there is a strong sense of place in her novels — something that is also central to her success. One may have never been to Naples, one may have never heard of the neighborhoods that she mentions, but thanks to her writing, to the sense of place that it produces, the reader becomes an inhabitant, a member of that community. And to an extent, there is an overlap between urban and psychological topographies. The reader is welcomed and integrated into them. But once again, there is nothing sentimental about it.

Ferrante’s portrayal of women’s lives is central to her work. In what ways do her novels contribute to or challenge feminist literary traditions?

Bellezza: Ferrante’s work provides a brutally honest and nuanced portrayal of women’s lives, struggles and aspirations. All her female characters grapple with societal expectations, gendered constraints and their own desires for independence, education and recognition. The way in which themes such as abandonment, effacement, rupture, loss, disappearance, wreckage are weaved into her stories is, in my opinion, a master class. Ferrante challenges traditional depictions of women by showcasing their flaws, complexities and resilience, rather than adhering to idealized or one-dimensional roles. This focus on women’s voices aligns her with feminist literary traditions while also pushing boundaries by engaging with themes such as female intellect, ambition and bodily autonomy in a way that students find extremely Impactful.

HBO

Telò: These novels appeal because, to use an expression of Judith Butler, “The bond is in the break” or “The break is the bond.” In other words, there is a fragility, a precarity to female solidarity that Ferrante is not afraid of bringing out and exploring in all its implications — even the most painful ones, those that we are afraid of discussing. Can we accept that female solidarity — like any other relationship — draws energy from its own breakability, from its adjacency to rupture and hostility? Competition and jealousy are the dangers of a break that keep solidarity together, as it were.

Welch: There’s an episode in The Story of a New Name that captures the cruelty of an education system designed to replicate the class hierarchy — a theme that runs throughout Ferrante’s novels. This cruelty shapes Lila and Lenù’s relationship, surfacing during a high school party at Professor Galiani’s house. There, Lenù is enthralled and intimidated by the intellectual posturing of boys who discuss concepts like colonialism, Gaullism and Marxism-Leninism, dropping names like Sartre and Nenni. Determined to fit in, she awkwardly contributes a few platitudes, briefly convincing herself of her own sophistication. Meanwhile, Lila, disillusioned by the pomp, tugs Lenù’s arm and whispers in dialect that she’s bored and wants to leave. On the car ride home, Lila hides how shaken she feels, resigned to a life of misery with her abusive husband, Stefano, while mocking the ruling class as “chimpanzees” and ridiculing Lenù for seeking their approval.

Ferrante dissects the brutal intersection of class and gender, exposing how it seeps into relationships and ambitions. Lila accuses Lenù of mimicking the bourgeois intellectuals to escape their shared neighborhood, warning that the system treats their world as little more than an ethnographic curiosity or a problem to solve. This moment encapsulates the tension between their ambitions, fears and the inescapable pull of their origins, laying bare the “ugly feelings” that Ferrante unflinchingly explores.

Eduardo Castaldo/HBO

Relationships are incredibly important throughout Ferrante’s work. Can you comment on how she writes about relationships and gender?

Bellezza: Central to Ferrante’s novels are relationships — whether familial, romantic or Platonic — and the female gaze. She captures the subtleties and contradictions within human connections, especially between women, and examines gender dynamics, particularly through the limitations placed on women in patriarchal societies. By portraying the violence, power struggles and emotional labor inherent in many relationships, readers are challenged to confront gender inequality and question traditional roles of femininity and masculinity.

Telò: Given my recent work on The Lost Daughter, I am particularly struck by the depiction of mother-daughter relationships. Ferrante is not afraid of telling us about mothers who feel resentment against their selfish daughters, who feel liberated when their daughters are out of the picture, who fantasize about their disappearance. It is still a taboo to say that maternity and mothering can be debilitating and unpleasant experiences — that they engender a kind of erasure of the mother, that they make the mother feel guilty if she doesn’t feel guilty about wanting to have some time for herself. Well, Ferrante violates this taboo. And she does so with courage, boldness and even fierceness. Maternal pain is connected with the most repulsive physiological aspects. Maternity leaves a perennial sense of hunger, which it is impossible to distinguish from melancholy (meaning, literally, “black bile”).

Jen Siska for UC Berkeley

Ferrante has long used a pseudonym and explains in her letters with publishers that once she has written a book, she is no longer involved in its life. This has made notable space for translators, film and TV writers and others to tell this story in various ways. How has this challenged tradition?

Telò: Yes, it is extraordinary that Ferrante has decided to embrace (and literalize, almost) the inevitable “death of the author” that writing entails. We live in times in which the publishing industry (the need for book presentations, book chats, conversations, book festivals, online events) has almost sought to disavow this fact. This is another expression of her boldness. She has responded to many of the letters of her readers, as one can see in her collection of occasional writings called Frantumaglia. And in these letters, one can see her refusal of policing readers’ responses, reactions and impressions. She is willing to be transformed by the process of reading. This is another example of solidarity in the break, if you will.

Welch: In 2015, when there was talk of her nomination for Italy’s most prestigious literary award, the Strega Prize, the author of an award-winning exposé of organized crime in Naples, Roberto Saviano, wrote an open letter in la Repubblica, pleading with her (Ferrante) to participate, in order to add a fresh voice to the “long stagnant swamp” of the Italian literary establishment. … She replied unflinchingly, declining to reduce her work to a “banner in a small cultural battle,” likening his request for her participation to someone asking her to use her books to “prop up an old worm-eaten table.”

I find this kind of ferocious integrity thrilling in a context usually reserved for humble self-effacement and genuflection — she’s basically accusing Saviano of “making use” of her work to breathe new life into an elitist institution, and refusing to take part.