Asta Mønsted, a specialist in prehistoric archaeology, reveals Greenland through the Inuit oral tradition

The UC Berkeley assistant professor prioritizes Indigenous knowledge and narratives, seeking to integrate them with scholarly theories and methods.

February 13, 2025

The news media is abuzz lately about Greenland, an Arctic territory just east of Canada and part of the kingdom of Denmark. The world’s largest island, it has about 56,000 inhabitants, most of them living in the 20% of Greenland that isn’t ice and snow.

President Donald Trump has publicly expressed his wish to buy Greenland from Denmark, in part to enhance security in the Arctic region, joining a list of other U.S. leaders who since the 19th century have wanted, or made unsuccessful attempts, to acquire the island.

Why is Greenland such a coveted place? Asta Mønsted knows, and she’s also well-versed in its fascinating history and archaeology. The UC Berkeley assistant professor and archaeologist, who joined the Department of Scandinavian in fall 2024, was born in North Greenland, does research on the Greenlandic Inuit’s oral history and teaches a campus course on Arctic folklore and mythology.

Inuit on her mother’s side and Danish on her father’s, Mønsted is bilingual. She values Greenland culture, which includes an emphasis on community, responsibility for others and respect for nature.

In an interview for Berkeley News with Sarah Fullerton of the Division of Arts and Humanities in the College of Letters and Science, Mønsted discusses her homeland, its oral history, folklore, language, history and the changing climate, and she tells why it’s vital for us to learn about and connect with the Indigenous people of the Arctic.

Niels Mønsted

Sarah Fullerton: Why has Greenland been such a focal point throughout history?

Asta Mønsted: Historically, Greenland has been significant, for example, during the search for the Northwest Passage in the 18th century. Expedition ships would travel along Greenland’s western coast in search of the passage, which put Greenland on the radar, so to speak, for European and American explorers.

Later, during the Cold War, Greenland became strategically important due to its geopolitical position amid tensions between the USSR and the United States. Various military bases were established there. Then, for a while, global interest in Greenland subsided. But now, tensions and competition have returned, particularly regarding access to natural resources, like rare earth minerals.

Jen Siska for UC Berkeley

About 10 years ago, Greenland also gained attention because of climate change. The massive ice sheets are melting at an alarming rate. One of the largest glaciers in Greenland north of the Arctic Circle, Ilulissat Icefjord, was moving at around 46 meters per day in 2012 — so about 17 kilometers per year. That’s a massive amount of ice breaking away, accelerating climate change. I’m an archaeologist, not a geologist, but it’s clear that this has a significant impact on the planet.

Greenland has been inhabited in multiple waves over the past 4,500–5,000 years, with the first people arriving from the North American continent via Canada when the sea froze in the narrow strait at Thule in northern Greenland. The ancestors of modern-day Greenlanders trace their lineage to the Thule culture, which arrived with the most recent wave of migration occurring around 1150 AD.

You’ve said in a previous interview that in Greenland, you can actually feel climate change happening. It’s not just something you read about in the news; you see it daily, right?

You really do experience climate change on a physical level. You can feel it, you can see it. I remember a scientist showing us a side-by-side comparison of an old photograph taken 100 years ago and a current image of the same location. In the older photo, there was a massive glacier and a small boat with someone sitting back, relaxing. In the present-day image, the glacier had dramatically shrunk, and the boat was a modern rubber boat. It was shocking.

People who live there feel the changes firsthand. For example, I come from the northern part of Greenland, from Uummannaq, where we experience about two and a half months of darkness each year. The first sighting of the sun is a momentous occasion, traditionally welcomed on February 4. But one year, the sun appeared a day early, leaving us all puzzled.

Asta Mønsted

The reason? The ice on a nearby mountain had melted so much that it no longer blocked the sun’s rays, allowing the sunlight to reach our town sooner. It was a striking, tangible reminder of climate change — something we could quite literally witness with our own eyes and feel in our own lives.

As an archaeologist, I also take a long-view perspective. Climate change has happened before, and we know the people of the Thule culture survived the last ice age: There are layers of histories in Greenland that show people have historically adapted. But today, we live in settled cities, unlike earlier communities that were highly mobile, following animals and natural resources. Now, we’ve locked ourselves in place, making it harder to adapt in the same way.

How are you connected to Greenland personally and professionally? And why did you choose to specialize in its archaeology and oral history?

I was born and raised in Greenland. My mother’s side is Inuit, and my father’s side is Danish. Growing up bilingual helped shape my perspective. My father, a civil engineer and amateur geologist, loved collecting rocks. One day, he showed me a stone tool that someone had started crafting, but abandoned. It was the first time I realized I was holding something shaped by another human — someone who lived there at the same spot long before me. That experience sparked my fascination with archaeology.

Asta Mønsted

Professionally, that interest led me to study prehistoric archaeology. In Greenland, artifacts are often just lying on the ground because much of the land is uninhabited, and cultural remains haven’t been buried under modern development. If you know what to look for, you can see ruins with the naked eye.

Storytelling was a regular pastime in Greenland because you live in darkness for months at a time. It was common for people to come together, sit by the lamp and tell stories in community.

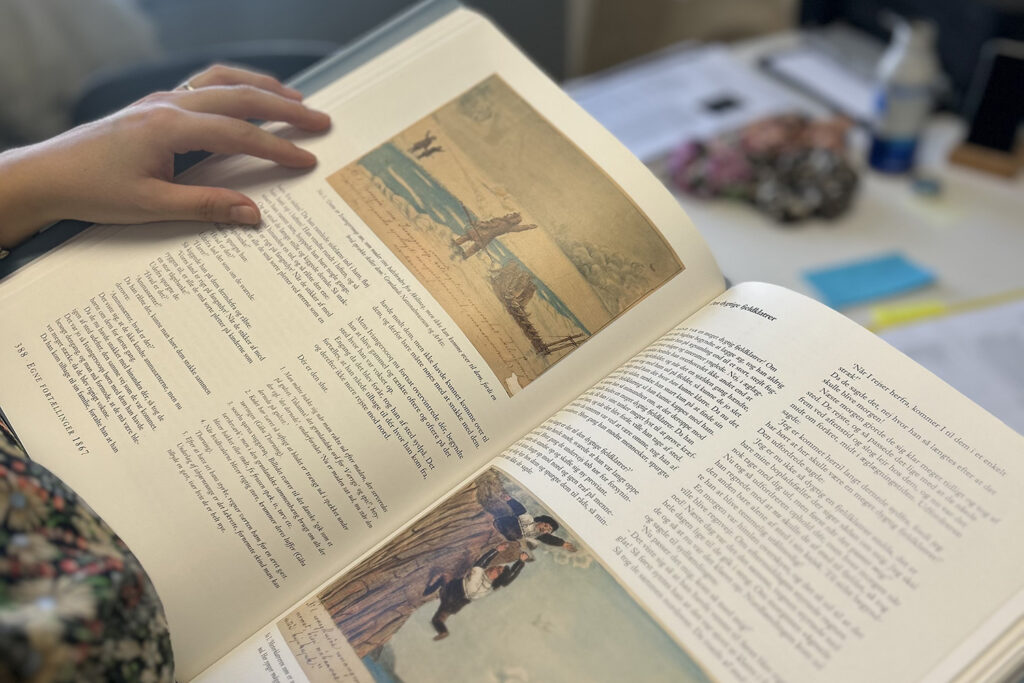

My work involves using oral history and archaeology together. Many myths and legends were passed down orally for generations before they were ever written down by colonizers. One well-known Inuit myth explains the origins of the sun and moon through a story about a brother and sister — one that also serves as a warning against incest. These stories carry deep cultural knowledge, guiding communities on survival, relationships and ethics. An important publication that captures some of these stories is called Således skriver jeg, Aron, and it has detailed illustrations by Aron Kangeq.

Is there a well-known story in Greenland’s mythology that shapes the culture today?

One of the most important stories in Greenlandic mythology and folklore is that of a young girl who defied her father when he deemed her ready for marriage. Refusing to comply, she was cast over the side of a boat by her father. As she clung to the edge, he cruelly cut off her fingers.

According to legend, she now resides at the bottom of the ocean. When people break taboos — such as overfishing, taking more than they need, or failing to treat one another with kindness — she withholds the animals. The shaman then descends to negotiate with her, acknowledging past mistakes and promising to do better. Because she understands what it means to be human, to go hungry and to struggle to hunt, she often grants a second chance.

Sarah Fullerton/UC Berkeley

This story serves as a powerful lesson in sustainability and responsibility, reminding us to respect nature, care for the animals and protect both our communities and the delicate relationships that sustain us.

You can see how stories such as this shape our culture today in Greenland. In other places in the world, individualism is often seen as something to value and take pride in. However, in Greenland, community and mutual care are essential. No one can survive alone in the harsh Arctic environment, so people must look out for one another.

If someone ventures out alone, it’s important to check on them. While individualism is often celebrated, in extreme conditions like these, balancing personal space with a strong sense of responsibility for others is crucial. Sometimes, caring for others means offering help even when they don’t realize they need it.

What significant archaeological discovery in Greenland should people know about?

The mummies of Qilakitsoq were a remarkable find. These were six women and two young children naturally mummified in a cave around 1475. They provide invaluable insight into the clothing, tattoos and way of life of Greenlandic people at the time. My mother’s cousin’s husband was actually one of the hunters who discovered them. At first, they didn’t even tell anyone because they were afraid of disturbing the site. Eventually, it became one of Greenland’s most famous archaeological discoveries.

Niels Mønsted

Why is it important for students to study oral history, folklore, language and ancient civilizations?

It is more important than ever to understand and engage with the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, given the political landscape we find ourselves in today. Greenland is at the center of major global issues — climate change, the growing interest in rare earth minerals, and its strategic geopolitical location — all of which have significant implications for its people and culture.

There are already numerous archaeological sites in Greenland under threat due to melting permafrost. As the ice thaws, coastal erosion intensifies, with waves encroaching on ancient settlements that were historically built near the ocean. This ongoing environmental shift puts invaluable cultural heritage at risk.

Studying specific places like Greenland helps us ask broader global questions: How did people survive extreme climates? How did they store food for winter? Lessons from indigenous knowledge can inform solutions for today’s climate challenges. While we are all global citizens, we’re also culturally rooted in specific places. Understanding these histories helps us connect those perspectives, and I’m teaching about these in my class this semester called Study of Arctic Indigenous Cultures.

For example, as an archaeologist working in Greenland, I find it fascinating to explore how prehistoric elements can inspire future architecture. Rather than relying solely on generic concrete buildings that could exist anywhere, we have an opportunity to create structures that reflect Greenland’s heritage and identity. By incorporating traditional influences, we can design architecture in which Greenlanders feel represented — where they see themselves and their culture mirrored, even in modern urban spaces.

NOTE: Patrick Farrell, video director for Berkeley’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs, contributed to this story.