Meet three Black trailblazers in STEM

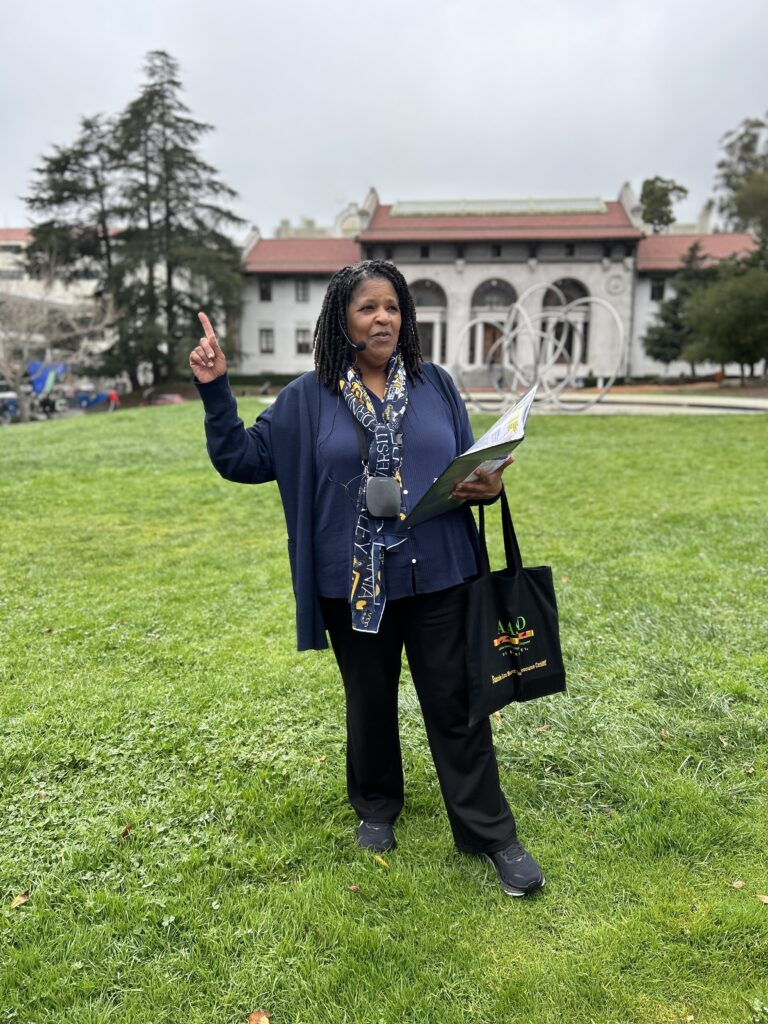

Berkeley alumni Lloyd Ferguson, Mary Blackburn and Marvin Poston paved the way for Black scientists and engineers. Black Lives at Cal is developing a tour that spotlights their stories.

Courtesy of Mary Blackburn

February 28, 2025

When Gia White attended UC Berkeley in the 1980s, one of her favorite professors was Barbara Christian, a founding instructor of African American studies at Berkeley. Christian, a scholar from the Virgin Islands, taught Toni Morrison and other Black women novelists in her class. Christian was the campus’s first tenured Black female professor.

Today, White is the administrative director of Berkeley’s Institute of European Studies and Global, International and Area Studies, and she stops at Christian Hall every time she leads a Black Lives at Cal history walk. White created the tour to highlight the campus’s long legacy of Black excellence, a history that might not be apparent to someone speed walking through campus, too worried about a looming deadline to Google the remarkable individuals behind the building names.

Lila Thulin/UC Berkeley

The tour grew from White’s volunteer role as a docent at Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, where she leads a different Black history walk. Several Black students from Berkeley’s early days are buried there; researching their backgrounds led White to dig into more alumni stories. Soon, she was browsing archival newspapers; reading a book from 1919, The Negro Trail Blazers of California; and listening to oral histories in the Bancroft Library. She learned not only about the very first documented Black student on campus — Alexander Dumas Jones, in the 1881 — but also Black women, such as Vivian Logan Rodgers from the Class of 1909, who defied racism and sexism to get their degrees.

“This is foundational knowledge for Black history at Berkeley,” said White. “There’s so much more than I put in the original tour.”

Some of that additional history will feed into a STEM-themed tour White is developing. The new tour was inspired, in part, by a group of STEM students visiting from one of the nation’s historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) two summers ago who wanted to know more about predecessors in their fields of study. White is also compiling the various profiles she’s researched into a book. She recently shared a preview of some of the people who will be featured on the soon-to-come STEM tour with UC Berkeley News.

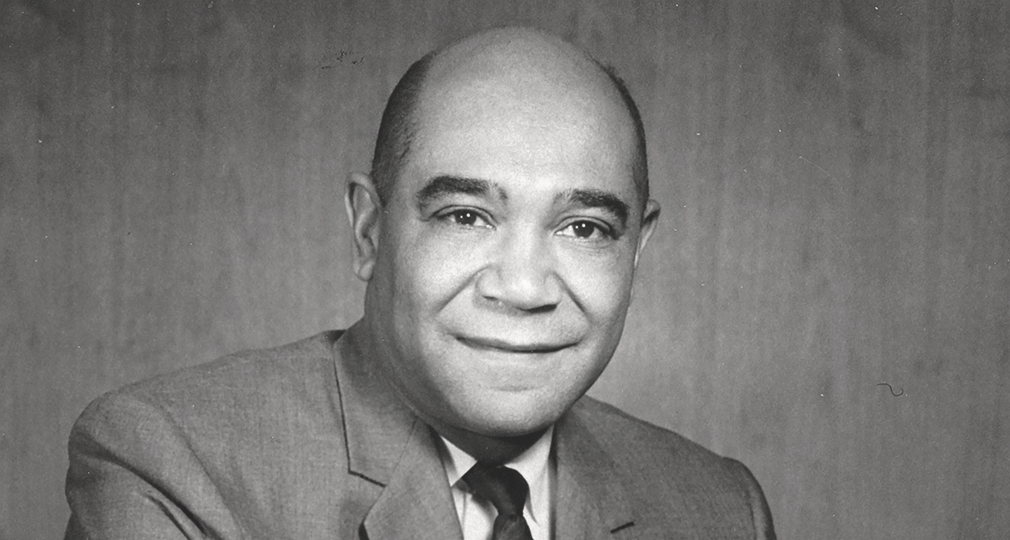

Lloyd N. Ferguson: B.S., 1940; Ph.D., 1943

“I always liked school. I couldn’t wait until the summer was over to begin again,” Lloyd N. Ferguson says in an oral history. Ferguson, the first Black student to graduate from Berkeley with a Ph.D. in chemistry, was born in Oakland in 1918 as a third-generation Californian. His interest in chemistry took root early. He built a makeshift lab in his parents’ backyard and worked, for a lofty 25 cents an hour, as an aide to Oakland Technical High School’s chemistry teacher, Ruth Forsythe, setting up lab experiments before class. The teen developed household concoctions he’d sell to neighbors — Moth-O, to repel the winged wardrobe pests, the spot remover Clean-O and a silverware polisher called Prest-O that he continued to use at home for the rest of his life.

Despite being an academic high achiever who graduated secondary school at 16, Ferguson didn’t go straight to college. In the midst of the Great Depression, he worked as a porter for Southern Pacific Railroad. In 1940, he graduated from Berkeley with a B.S. with honors and stayed there to complete a Ph.D. in chemistry, which he finished in three years. His thesis work involved finding a compound that could store and release oxygen for military purposes; the material his team developed was later put to use.

Throughout his entire education, Ferguson had never had a Black teacher, but he’d go on to become one himself. While he initially planned to enter the corporate world after graduate school, a mentor told him that the major chemical companies wouldn’t hire a Black man. Instead, he joined the faculty at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College and then at Howard University, where he spent 20 years, chaired the department and began the first chemistry Ph.D. program at an HBCU. Later, he returned west to California State University, Los Angeles, where he worked for another 21 years.

Over his career, Ferguson authored seven textbooks — including one that ironically was used at the University of Mississippi as the school was pushing back against integration — researched subjects as wide-ranging as chemotherapy and the molecular structure of sweet and sour substances, won a Guggenheim award that allowed him to work in Denmark and helped establish the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists and Chemical Engineers.

Ferguson died in 2011 at the age of 93.

Mary Blackburn: Master of Public Health, 1965; Ph.D., human nutrition science and health administration and planning, 1974

Courtesy of Mary Blackburn

Mary Blackburn’s road to Berkeley was long — 2,087 miles, to be exact. Blackburn grew up in the South as one of 13 children in a sharecropper’s family. The first in her family to attend college, she had just graduated from Tuskegee University, an HBCU, when she was selected to be part of the inaugural cohort of Berkeley’s Combined Dietetic Internship–Master of Public Health program in 1963. The pilot program, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services as an evolution of the home economics field, would train registered dieticians, a growing profession spurred by World War II.

Blackburn had four young children and lived states away in Jim Crow Alabama, but her parents volunteered to care for her kids until she secured housing in the East Bay. After earning her degree and becoming one of the country’s first registered dieticians, Blackburn continued at Berkeley to receive a Ph.D. in human nutrition science and health administration and planning in 1974. Despite her academic qualifications, she was fired twice on account of her race, but she continued to forge a successful career in health and nutrition.

“Mary Blackburn has really made a difference in the lives of Bay Area residents. Her work with local communities makes it easier for people to stay active and eat healthy food,” said Glenda Humiston, vice president for the UC Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Blackburn has worked there since 1990, and Humiston’s comments came as the division celebrated their longtime employee winning a national Hall of Fame award in her field.

Drawing on her life experiences, Blackburn has researched subjects including pregnant teens and women’s nutrition and energy expenditure, the nutritional needs of family units where grandparents serve as children’s primary caregivers, chronic disease among limited-income seniors and disaster readiness. As a UC Cooperative Extension nutrition, family and consumer sciences adviser for Alameda County, Blackburn spearheaded projects like launching a gardening project for a group of senior citizens living in affordable housing in Oakland and nutrition education programs for low-income communities.

White learned of Blackburn, who is in her late 80s and still lives in the Bay Area, from emeritus Berkeley entomologist Vernard Lewis and interviewed her to glean details about her experience at — and after — Berkeley to add to the tour.

Marvin Poston: B.S., optometry, 1939

Courtesy of the Poston family

If you experience the world as a blur without the aid of glasses or contacts, you’re likely familiar with VSP, a popular vision insurance program. If so, a Black Berkeley alumnus is behind your subsidized lenses. Marvin Poston was the first Black optometrist trained at Berkeley; he earned his degree in 1939, and the program wouldn’t produce a second Black graduate for more than two decades.

Poston’s upbringing crisscrossed North America. After being born in St. Louis, Missouri, to a teacher and a housewife who encouraged their children to strive for higher education, his family moved to Edmonton in Alberta, Canada, but later relocated to Oakland. Poston, like Ferguson, attended Oakland Technical High School and worked to pay for his college education. In Poston’s case, he helped his mother sell insurance and manned the 4 p.m.-1 a.m. shift at the Oakland Athletic Club throughout high school and college.

As a math and physics major at Berkeley, Poston intended to become a math teacher in Oakland, but he learned the job opportunities for Black educators in the city were limited by racist policies. So he changed his path of study to focus on optometry, which was then part of Berkeley’s physics department.

“Of course, when I got in, that’s when all hell broke loose.”

Marvin Poston

“Of course, when I got in, that’s when all hell broke loose,” he says in an oral history recorded in the 1980s. When Frederick Mason, an instructor in the program, “saw Black, he saw red,” Poston remembered. Mason blocked Poston from being assigned patients in the clinic, told him he “didn’t think a Black person could be an optometrist” and later threw up roadblocks to Poston’s admittance to the state board and the Alameda and Contra Costa Counties’ Optometric Society. Poston had the last laugh, becoming president of the latter in the ’60s.

Some members of the Berkeley community rallied around Poston to help him excel, despite the discrimination he faced. When Mason wouldn’t answer Poston’s questions in class, his Jewish classmates would reiterate his queries for him. And with the intervention of attorney Walter Gordon — the first Black Berkeley Law alumnus and the campus’s first All-American football player of any race — and Berkeley YMCA General Secretary Harry Kingman, the campus administration made Mason’s class an elective instead of a requirement so Poston would not have to interact with him any longer. (Mason continued to teach at Berkeley until 1953.)

During his time on campus, Poston played for the varsity ice hockey team and was a member of the student NAACP chapter, where he would team up with white students to enter restaurants, be refused service and then sue the establishments for their segregationist policies.

Poston established an optometry practice in Oakland and became the first licensed Black optometrist on the West Coast. He served several terms on the State Board of Optometry and in 1955 co-founded California Vision Services, which began as a prepaid vision plan for union members and grew into VSP Vision, the organization that today provides insurance for about one in four Americans.

He retired to a vineyard in Calistoga in the Napa Valley — becoming the first Black vineyard owner in the famed viticulture region — and died in 2002 at the age of 87.

Sign up for the current offering of Black Lives at Cal’s Black history walking tour here or listen to a self-guided audio tour.