How Trump’s immigration policies compare to those of America’s past

Hidetaka Hirota, a UC Berkeley professor who studies immigration law history, discusses the deep roots of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States.

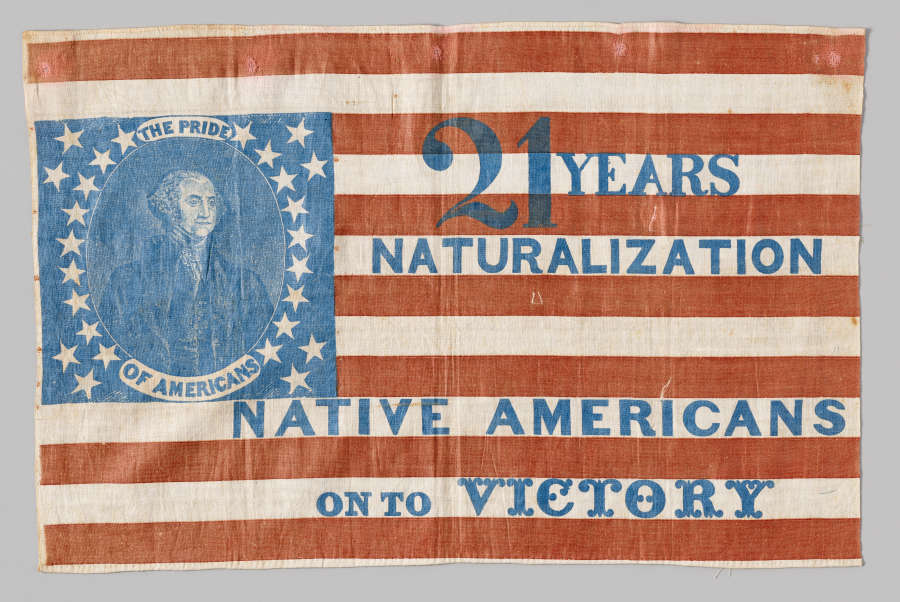

National Archives

March 4, 2025

On the campaign trail, President Trump made his promise to drastically slash immigration a rallying cry. Since taking office, he’s issued a flurry of executive orders aimed at achieving those goals, from ending birthright citizenship to freezing funding for refugee resettlement and migrant legal aid organizations.

Immigrant rights groups have responded with lawsuits challenging the legality of these orders and report a climate of fear that is making people question whether to accept farm jobs or take children to school.

Trump’s rhetoric and policy actions alike are dramatic. But heated political conversation about immigration, laced with issues of race and class, is nothing new in the United States. Trump’s executive actions are the latest entry in the long saga of our nation’s fraught relationship with immigration, a subject on which Hidetaka Hirota, an associate professor of history at UC Berkeley, is an expert.

Courtesy of Hidetaka Hirota

Hirota studies American immigration law, stretching back even before the U.S. was formed. Anti-immigrant, or at least anti-outsider, sentiment has existed throughout our nation’s past, he says, and many tensions over labor and race that fuel immigration debates today are continuations of a centuries-old standoff.

“Trump is really outstanding, in a sense. He is bold,” Hirota said. “But at the same time, his language, his approach, the way he views immigration were actually built on earlier discourses.”

Recently, Hirota spoke with UC Berkeley News to provide historical context for Trump’s attempts to end birthright citizenship, explain how demand for immigrant labor has shaped U.S. policy and share his perspective on America’s shifting attitude toward migration.

UC Berkeley News: America brands itself as a nation of immigrants, but your research has shown that deportations and strict immigration laws stretch all the way back to the colonial era. What are the roots of American immigration law?

Hidetaka Hirota: There was no period in American history where borders were entirely open. Since the colonial period, there has always been some form of restriction.

One of the earliest forms that we can find is restriction against impoverished people, or “paupers” or “vagrants,” as they were called. It’s a system that the colonists inherited from England. When they came to America, they brought with them this English system of expelling from their community indigent people who did not belong to the town or the parish. It’s a policy based on economic considerations that the community should not spend their treasury on the support of outsiders. This was not necessarily an immigration policy; it’s a measure to control the movement of the poor. But eventually, as the United States became a nation, this policy began to operate as immigration policy, especially during the 1840s and ’50s, when the Northeastern states received a lot of indigent Irish immigrants.

Public domain

Eventually, those policies laid the legal and administrative foundations for later federal immigration policy, which developed from the late 19th century onward. The rest of the history of immigration policy is well known. Starting with Chinese exclusion, the federal government continuously expanded the category of prohibited immigrants.

The very concept that the United States is a “nation of immigrants” is actually a political construct from the 1960s. Since the 1920s, immigration from southern and eastern European countries was heavily reduced under the quota system, and Asian immigration was virtually suspended. After World War II, especially during the Cold War, there was this idea among liberals that America should free itself from this racist immigration system. That’s when this idea of the United States as a nation of immigrants really emerged.

The concept helped abolish discriminatory immigration laws by celebrating the nation’s immigration past, but it has its own problems. While highlighting the inclusive aspects of American immigration history, it minimizes its restrictive aspects. This is something I explain on Day 1 of my immigration history class at Berkeley.

A lot of political controversy surrounds labor and immigration right now between business owners in conservative states who are concerned about losing workers or reports that Elon Musk and Trump have split with some other conservatives over the issue of H1-B visas. Historically, how have labor and immigration been related?

It’s a core theme in American immigration history, this constant tension between parties that relied on immigrant labor and those that didn’t want to have those immigrants for racial, economic or religious reasons. As early as the 1830s and ’40s, you see this discourse in Boston, for example. Irish immigrants were poor, and Americans thought that they would work for low wages. There were hand bills circulated in Boston saying, “Beware of pauper labor.”

Chinese exclusion policy, which banned the entry of Chinese laborers, met harsh opposition from capitalists and owners of railroads, who relied on Chinese labor. But anti-immigrant labor policy prevailed when American labor unions, led by the Knights of Labor, persuaded the federal government to pass the Foran Act of 1885, which prohibited individuals and companies from importing contract workers, believing that those imported workers would be strikebreakers and lower wage standards. This law applied widely to Asians, Mexicans, Europeans, even Canadians, up to the 1920s. But in the meantime, the law was constantly evaded and violated by the parties who wanted immigrant labor. In the Southwest, unauthorized importation of Mexican workers was the norm. And the federal government was essentially powerless in preventing the law evasions by American employers.

The tension that we see over immigrant labor is nothing new; it has long been part of American history.

Are there parallels you see between some of the othering language that’s used today, like “illegal alien,” and language you’ve seen in historical documents?

There was a term that was used against immigrants who were imported by employers, which was “artificial immigration” or “unnatural immigration.” Except the most radical nativists, opponents of immigration at the turn of the 20th century tolerated immigrants who came to the United States voluntarily, especially if they were European. But they thought that the immigration of contract workers who were imported by business owners was stimulated by capitalist interests rather than immigrants’ free will. Today’s binary is between “illegal aliens” and “lawful immigrants.” But back in the day, it was “natural immigrants” and “unnatural immigrants.”

“Trump is really outstanding, in a sense. He is bold… But at the same time, his language, his approach, the way he views immigration were actually built on earlier discourses.”

Hidetaka Hirota

In 2018, you wrote a piece for the Washington Post about the “long history of denial of citizenship in this country.” Could you elaborate?

We always see this discrepancy between legal citizenship and the social treatment of that person. U.S. citizens are not always treated as such. In my book, Expelling the Poor, I demonstrate how, in the 19th century, native-born American children and naturalized citizens of Irish descent were deported from Massachusetts. That was before the 14th Amendment, which defined U.S. national citizenship. Before that, there was no constitutional definition; people simply assumed that if you’re born in America, you’re a citizen. Such citizenship was very fragile.

The 14th Amendment defined national citizenship and then established protections. But unfortunately, there were a lot of examples when U.S. citizenship was disregarded in practice — for example, the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Two-thirds of the people of Japanese descent who were incarcerated were U.S. citizens. Incarcerating citizens without any valid excuse, with their due process being denied — that’s one tangible example of how American citizens were treated as non-citizens. During the Great Depression, Mexican American citizens were “returned” to Mexico, even though many of them were born in the U.S. and had never visited Mexico. That’s another case of how U.S. citizens were treated as non-citizens at the practical level. Threats to citizenship today are just the latest chapter of this long history.

Looking at the long history of U.S. immigration law, when was it most restrictive? Where do we stand right now relative to then?

The period between 1924 and 1943 was arguably one of the most restrictive periods because immigration laws during this period were expressly discriminatory, by suspending Asian immigration and substantially reducing immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe, compared to the “preferred” countries in Northern and Western Europe. The Chinese exclusion laws were lifted during World War II, in 1943.

At the same time, the scale of operation and the amount of money that is put into border control and law enforcement now are far larger than any [other] moment of U.S. history. Earlier, the law itself was strict, but its practical implementation was often loose and suffered a lack of funding and understaffing. Today, it is much more difficult to enter the United States and obtain citizenship status or permanent residence, compared to earlier periods.

On January 20, Donald Trump suspended refugee resettlement. Historically, what has been the role of refugees in immigration policy?

As a legal category, it’s relatively new. The category was created after World War II, in part to accommodate Jewish people who fled from the Nazi regime. The history of refugee policy is that refugees were often admitted on presidential parole. Presidential parole power allows the president to admit non-citizens, regardless of congressional immigration policy. That authority was often the basis of refugee admissions to the United States, precisely because U.S. immigration policy was so slow in responding to refugees.

There was always hesitation to admit refugees, especially after the 1970s. Earlier, for example, refugees were largely Europeans — let’s say, Hungarians in the 1950s, and the American public was relatively open to those refugees as future citizens. But since the 1970s, as refugees became, for example, Asian groups, like the Vietnamese, and then Latin Americans, there was very strong opposition. It’s really racialized.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.