William Kentridge’s ‘The Great Yes, The Great No’ is a voyage of chaos and creativity

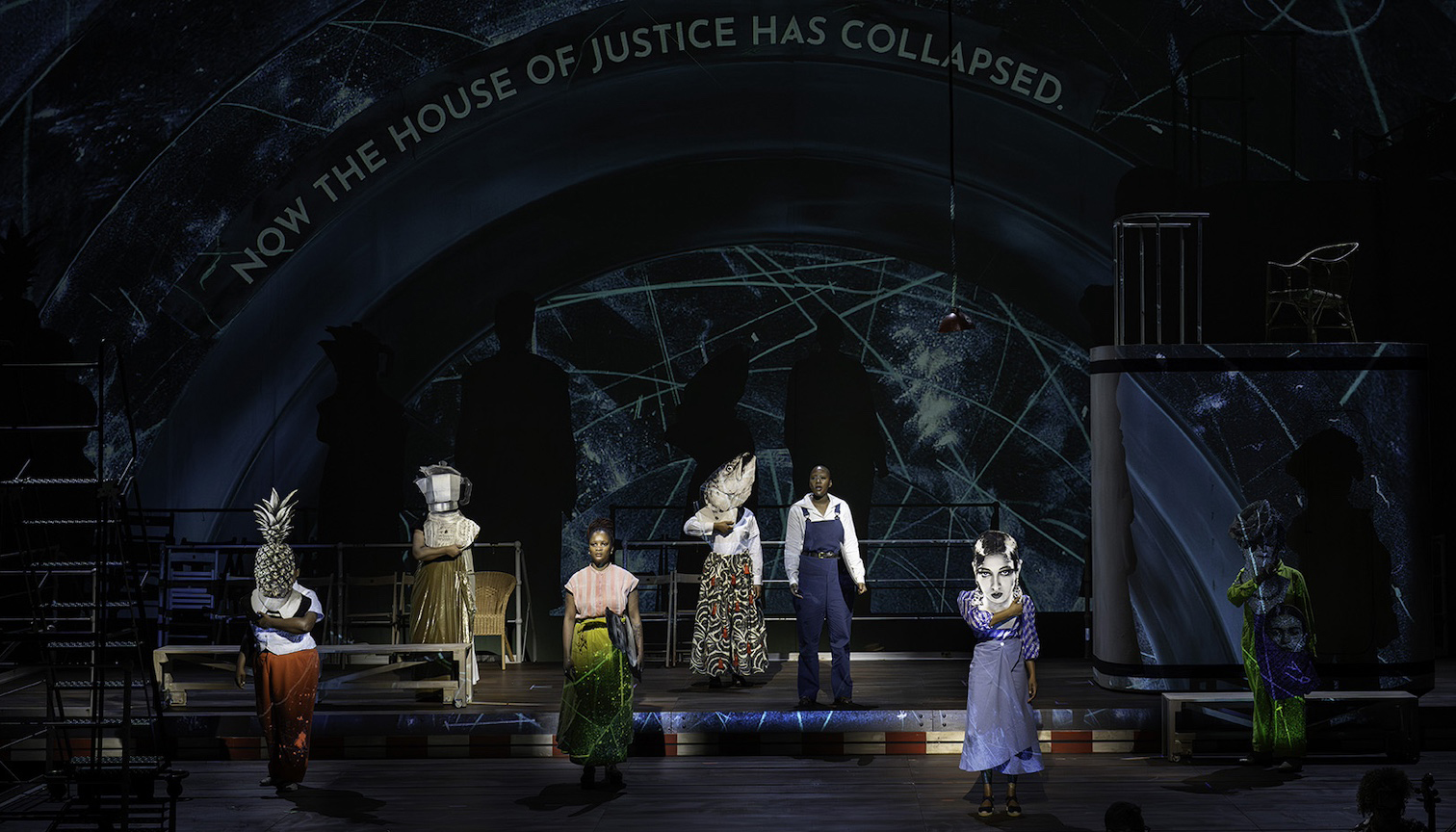

A menagerie of notable thinkers escaping the Nazis during WWII come together on a “ship of fools” in the South African artist's latest chamber opera, co-commissioned and presented by Cal Performances March 14-16.

March 11, 2025

South African artist William Kentridge is not interested in being certain. With certainty, he believes, comes a stuckness. Whether as a way of making artwork or in thinking about the world, certainty closes a person off to a more expansive creativity, to seeing all the possibilities that aren’t immediately or obviously perceptible.

“One must be open to mistakes, to things that don’t work,” he says. “Not so much celebrating things that don’t work, but being open to suggestions, ideas that come from the cracks in the work and from the margins.”

Marc Shoul

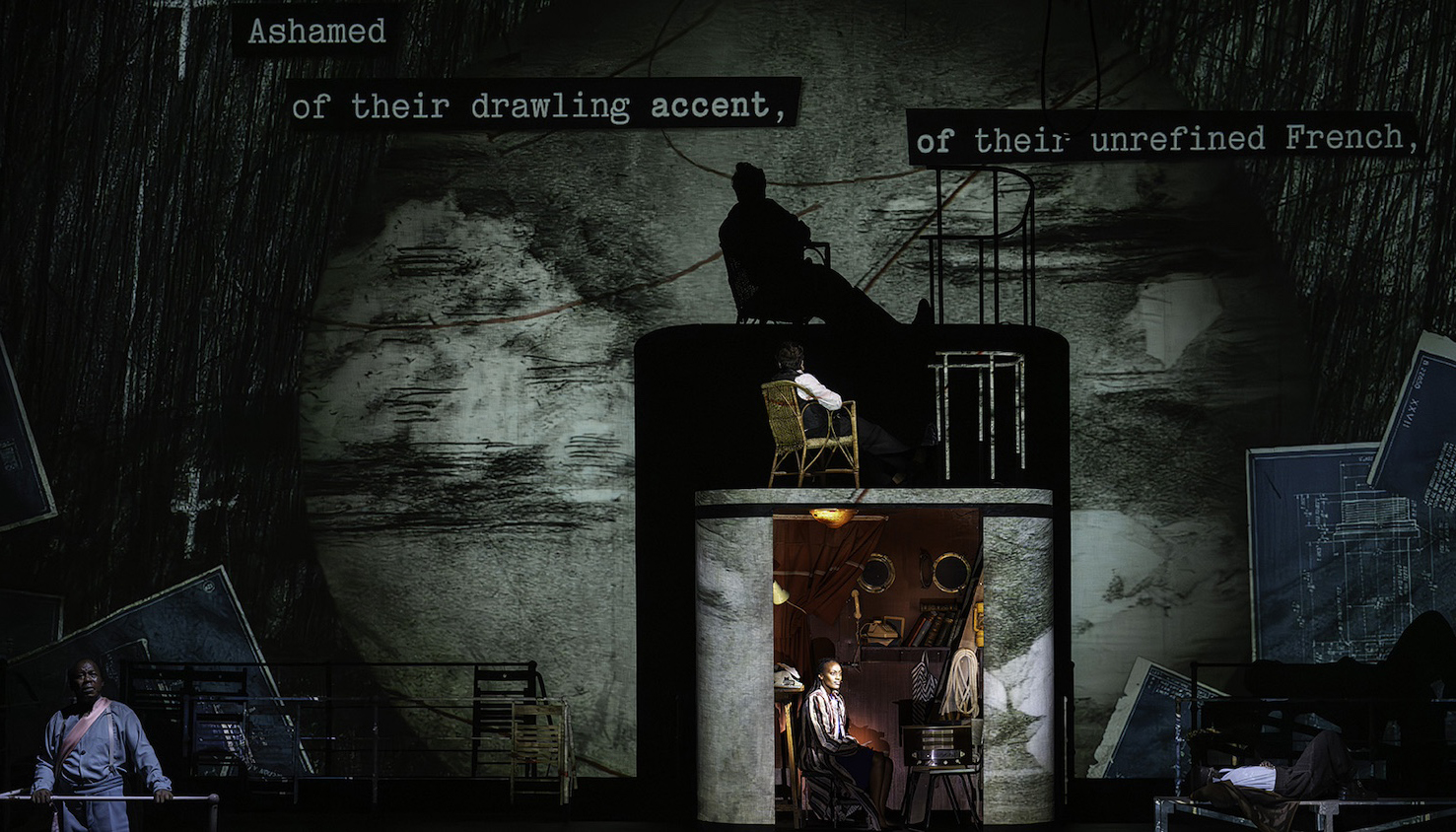

In his work, which explores themes of displacement and identity through charcoal drawings, animated films, sculpture, plays and opera, Kentridge has embraced new ways of thinking about the world and how humans exist with one another. Known for his nontraditional animation technique, Kentridge will film a drawing, make changes to it and then film it again. Traces of the figures that came before remain visible.

To create a space for artists to pursue “incidental discoveries” through experimentation and collaboration, Kentridge co-founded the Centre for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg in 2016. The name of the arts center comes from an African proverb: “If the good doctor can’t cure you, find the less good doctor.” Since it opened, it has produced nearly 500 performances, films and installations with more than 800 artists collaborating on projects across various disciplines.

From March 14-16, UC Berkeley’s Cal Performances is presenting Kentridge’s latest piece, The Great Yes, The Great No, a chamber opera it co-commissioned as one of the pieces in this season’s Illuminations series, “Fractured History.” The series explores the dynamic and ever-changing nature of history through performances, public programs and academic encounters.

Set on an old cargo ship that smells of rotting oranges, The Great Yes, The Great No is based on a real voyage that took place in March 1941. At the vessel’s helm was SS Capitaine Paul-Lemerle, and on board were more than 300 refugees fleeing the Nazis in France, bound for the Caribbean island of Martinique. Among the travelers were some of the great thinkers and creators of their time, from French surrealist André Breton to Cuban artist Wifredo Lam to anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who wrote about the voyage in his 1955 memoir Tristes Tropiques.

In the opera, Kentridge blends this historical event with other forced migrations, bringing together a mix of characters that draw both from the real events of the 1941 voyage and other periods throughout history. They include people like Martinican poet Aimé Césaire, entertainer Josephine Baker and Joséphine Bonaparte, who was born in Martinique and later became empress of France. Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin also make appearances.

For the passengers, the voyage is miserable, yet raucous and full of life. They’re living in a kind of limbo, leaving a home that doesn’t want them for a place that will mistreat them.

“It’s a bit like the traditional medieval image of the ship of fools, all of society compressed into the small space of a boat,” says Kentridge. There is lament on the boat, he says, but also a lot of dancing and singing. “Even in times of severest woe,” he says, “there are moments of joy and celebration that force their way through.”

For 90 minutes, The Great Yes, The Great No explores themes of exile, resistance and the complex dynamics of colonialism through surrealist imagery and performance elements. The libretto draws inspiration primarily from Césaire’s book-length poem, “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal,” or “Notebook of a return to my native land.” The all-female chorus performs music in eight different languages of South Africa. (English translations will be projected on a backdrop screen.)

Jen Siska/UC Berkeley

Mario Tèlo, a Berkeley professor of rhetoric, comparative literature and Ancient Greek Roman studies, is working with Berkeley rhetoric professor Jim Porter on an edited collection about Kentridge, provisionally titled William Kentrdige’s Antiquity: Medium, Surface, Discord, to be published in 2027. He says Kentridge’s art has a palimpsest quality — traces of its earlier forms remain, suggesting that there’s always room to challenge and grow and remake any work throughout history.

“This aesthetic unfinishedness — always displayed, always magnified in Kentridge’s work — can offer inspiring ways for reapproaching ancient artworks, which we tend to view as closed-off, self-contained, monumentally constricted by and within their untouchable completion,” says Tèlo.

For the book, Tèlo says they’re collecting essays from an array of scholars working across the humanities, which will reflect Kentridge’s “bold, radical process of intermedial unmaking.”

It’s a time of great uncertainty for the characters in The Great Yes, The Great No — a time when they hold both pessimism and optimism together, says Kentridge. “One cannot survive without optimism,” he says, “but one has to also understand the difficult and impossible circumstances of migrants, both in the terms of the story of people going from Marseille in 1941, but obviously before and after this.”

There isn’t a central message of the performance that Kentridge hopes the audience grasps. Rather, it’s the unmaking, the unraveling of ideas and stitching them together in a different way, that he hopes will inspire an openness to understanding, and an invitation to construct the performance as they see it.

“It’s not as if we start with certainty or knowledge, and then illustrate it for an audience,” he says. “We start with a mess of different possibilities and hope that from this, provisional coherences can be made. You have to let your eye and your ear guide you and shape what you’re seeing and hearing, and see if that provokes any echoes inside.”

Tèlo says that Kentridge’s work — the result of his long-standing anti-racist activism in South Africa — could not feel more timely.

“It urges us to question the very idea of the nation state,” Tèlo says, “considering borders as mere lines — wounds, but also precarious markers, which can be constantly rearticulated, redefined, redetermined, getting lost in an intricate palimpsestic web, never stabilized, always in process.”

Toward the end of the opera, after surviving a treacherous storm, the passengers land in Martinique, where they will live as outsiders. “Love no country, countries soon disappear,” sings a member of the chorus, a collective voice calling out to the audience.

And later, she sings: “The world is out of kilter. We will reset it.”

As part of the Illuminations program, Berkeley’s Center for Interdisciplinary Critical Inquiry will co-host a pre-performance panel with Kentridge on opening night titled “Surreal Histories.” The discussion will be moderated by the center’s director, Debarati Sanyal, and is free and open to the public, even those without tickets to the show. The cast will also participate in a post-performance discussion immediately following the closing performance, free to all ticket holders that day.