Got eggs? This UC Berkeley museum has tens of thousands.

The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology has one of the largest collections of eggs in North America, and it's vital to researchers worldwide.

April 11, 2025

It’s the season for egg hunts, whether you’ll be searching for the plastic, candy-filled kind or — due to the avian flu outbreak — an affordable dozen at the grocery store.

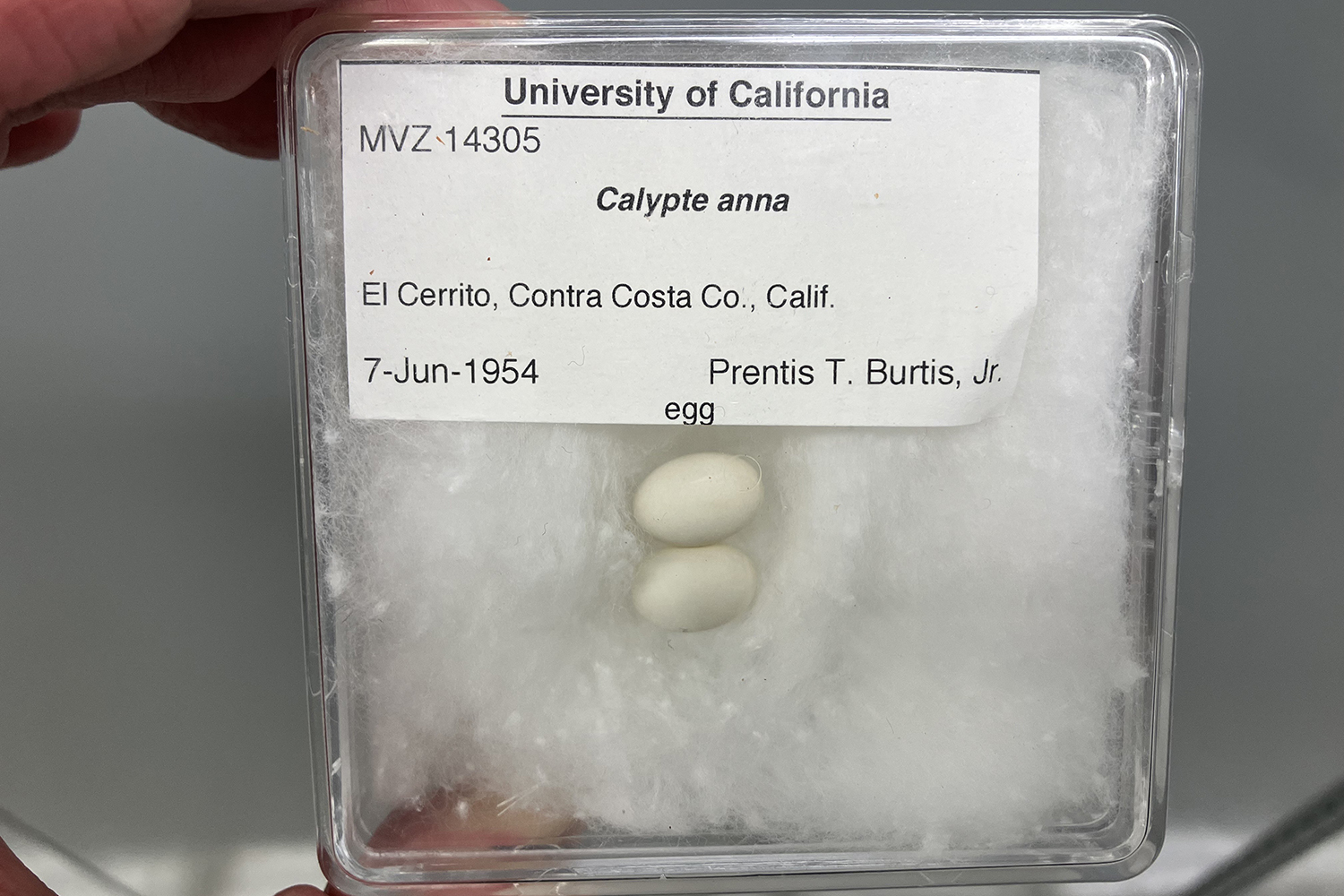

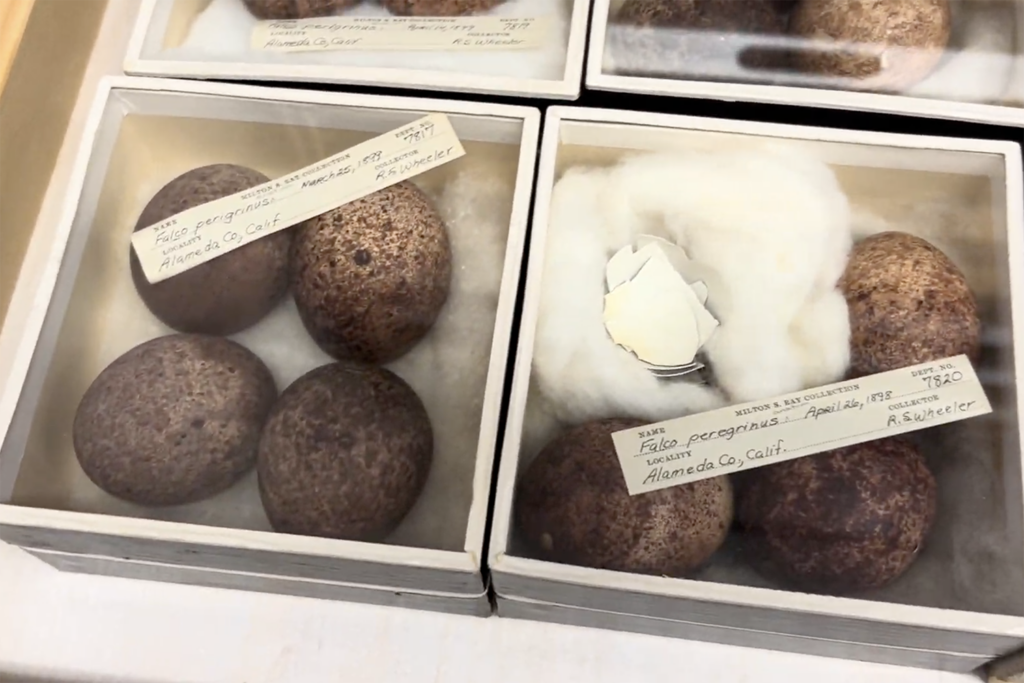

At UC Berkeley, there are nearly 14,800 sets of bird eggs — 57,883 eggs in all — and 1,300 bird nests at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. The museum has one of the largest collections of eggs in North America.

In the drawers of custom-made steel cabinets, the egg specimens are stored in boxes with see-through tops so they can be viewed without handling. The cabinets have airtight rubber seals, since the museum doesn’t use chemicals to deter pests.

Marissa Gutierrez/UC Berkeley

The tiniest eggs are from hummingbirds, the biggest from the long-extinct elephant bird. There are oblong, round, speckled, pastel-colored, textured and even pesticide-damaged eggs. The majority are from western North America, the rest from most other continents.

There even are specimens from nearly every extinct North American bird species.

The museum is primarily a research facility for scientists and graduate students. However, it offers many tours, including for local school groups and for classes on the Berkeley campus. In 2024, it hosted 31 tours for about 735 visitors.

Rauri Bowie/UC Berkeley

The eggs and nests are too fragile to be loaned, so researchers and anyone at a distance can view them, along with their data, in the museum’s online records. Here’s a peek at the museum’s oldest egg specimen, a single egg from 1860 from the extinct passenger pigeon.

In 2024, researchers accessed the online egg collection 7,841,030 times, said Rauri Bowie, Berkeley professor of integrative biology and a curator at the museum. He added that in 2024 alone, data from the museum’s bird collection were viewed online 134,145, 380 times.

Charlotte Khadra/UC Berkeley

Today, collecting and possessing wild bird eggs is generally illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and other laws. The eggs in the museum primarily stem from the 1800s and early 1900s, when egg collecting was popular. Today, new specimens are added occasionally to the collection through salvage, gifts and confiscations by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Recently, the museum received and catalogued 83 egg sets and four nests. They were donated by the son of a former Berkeley alumnus who collected eggs as a hobby in the 1930s.

It also accepted a donation of 520 egg sets that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service took possession of following the death of another egg collector.

Bowie said the museum is fulfilling the vision of its founding director, Joseph Grinnell, a professor of zoology. It’s doing so by making novel discoveries through the comparison of specimens, including eggs, using time series data and the exceptional field records that Grinnell and his colleagues preserved.

Charlotte Khadra/UC Berkeley

“Eggs are remarkable structures,” said Bowie, “and with each new advancement in technology, we uncover even more about them. They offer a window into the past, allowing us to study the effects of environmental contaminants, like DDT, and climate changes, such as shifts in egg and clutch size.”

The museum’s collections also help scientists learn how plant materials used in nest-making can guide habitat restoration efforts, he added, “helping us uncover the original plant species that once thrived in areas like San Francisco Bay, the Galápagos Islands and beyond.”