Berkeley Talks: The case for a philosophical life, with Agnes Callard and Judith Butler

The scholars discuss how the work of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates can help us to ask and answer life’s most important questions.

April 18, 2025

Follow Berkeley Talks, a Berkeley News podcast that features lectures and conversations at UC Berkeley. See all Berkeley Talks.

The ancient Greek philosopher Socrates is considered the father of Western philosophy, one whose most famous ideas have all but risen to the level of pop culture.

We parrot his claim that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” His name has been invoked by politicians to bolster their stance against “cancel culture.” There’s even an AI chat app modeled after Socrates that promises intelligent conversations.

UC Berkeley

But what exactly were Socrates’ philosophical views? We may be quick to reference his name, but if asked, many of us would likely be hard-pressed to give a thorough account of what he actually believed.

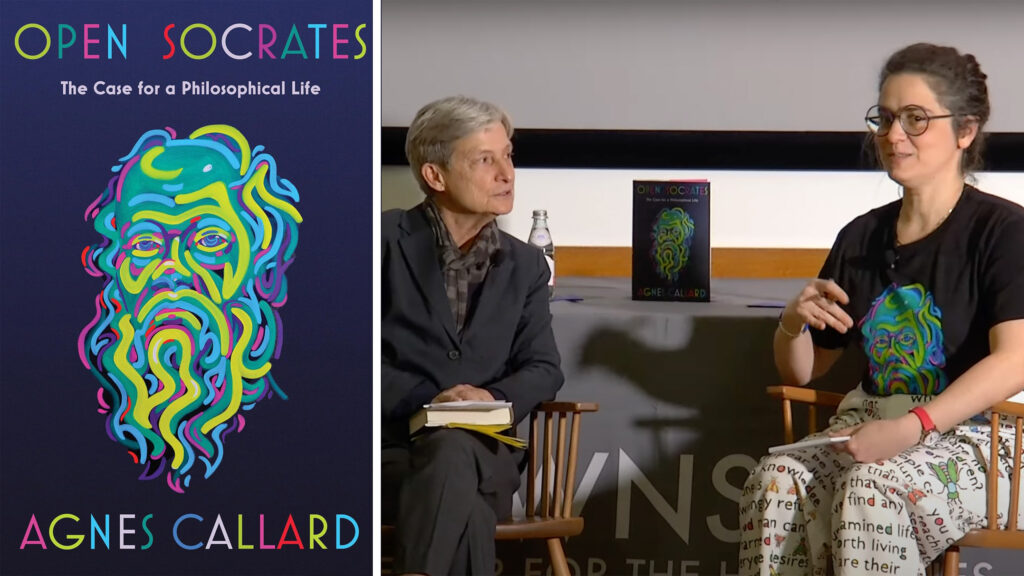

In Berkeley Talks episode 224, Agnes Callard, an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago and author of the 2025 book Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life, joins UC Berkeley’s Judith Butler, a Distinguished Professor in the Graduate School and a leading philosopher and theorist, for a conversation.

Together, they dive deep into Socrates’ work and beliefs, discussing the value of pursuing knowledge through open-ended questions, how philosophical inquiry is a collaborative process where meaning and understanding are constructed through conversation, and how critical questioning can lead to greater freedom of thought and help us to ask and answer some of life’s most important questions.

This event took place on Jan. 30, 2025, and was sponsored by UC Berkeley’s Townsend Center for the Humanities.

Watch a video of the conversation.

(Music: “Silver Lanyard” by Blue Dot Sessions)

Anne Brice (intro): This is Berkeley Talks, a UC Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs that features lectures and conversations at Berkeley. You can follow Berkeley Talks wherever you listen to your podcasts. We’re also on YouTube @BerkeleyNews. New episodes come out every other Friday.

Also, we have another show, Berkeley Voices. This season on the podcast, we’re exploring the theme of transformation. In eight episodes, we’re looking at how transformation — of ideas, of research, of perspective — shows up in the work that happens every day at Berkeley. You can find all of our podcast episodes on UC Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

(Music fades out)

Sylvie Thode: Thank you all so much for being here this evening. My name is Sylvie. I’m a Ph.D. candidate in English, and I’m honored to be introducing Professor Agnes Callard and Professor Judith Butler, who will be engaging tonight in a conversation inspired by Callard’s new book, Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life, published this month by Norton. First, though, I’d like to thank the Townsend Center staff for making this event happen and the Berkeley AV staff for helping everything run smoothly.

Many of us in this room may think we know who Socrates was and who he is to us now. We may have been taught that he’s the father of Western philosophy, but if asked, we might find ourselves hard-pressed to give a thorough account of his views. He is famous for his humility, but students frequently find him and his sense of irony condescending or even obnoxious.

A whole host of things fly under the banner of Socrates these days. United States congressmen have trotted him out in the name of cancel culture. The Los Angeles Board of Education offers cheery resources for how to lead a Socratic seminar on controversial issues. An AI chatbot modeled after him called, as it happens, socrates.ai, promises intelligent conversations perfect for students, professionals, and anyone seeking an immersive conversation experience. Socrates, if you’re wondering, gets a respectable 4.6 out of 5 stars on the app store.

Agnes Callard’s Open Socrates cuts through 2,500 years of din around this most central yet enigmatic figure of Western philosophical thought and reintroduces us to someone whom we all claim to already know. Unlike our approaches to Kantianism, utilitarianism, or virtue ethics, whose ethical programs have come to dominate contemporary philosophical life, Callard suggests we think of Socratic thought less as a concrete ethical theory and more as a critical thinking sauce that can be poured over anything from other philosophical systems to simple common sense. Hence, we tend to understand Socrates’s contribution to the work of philosophy as more of a method of approaching ideas rather than a program, more a way to run a classroom rather than ethics one might actually teach within its walls.

In Open Socrates, Callard rejects those assumptions and makes the case for what she calls Socratic intellectualism, which exhorts a person to organize her life around the pursuit of knowledge. So what does that look like? The answer is both simple and exceptionally challenging. Whereas other philosophies argue with each other over who has the best answer for how we should respond to the events of what we call real life, events like marriage, breakups, the making of art, war, sickness, work, death, Socratics believe that asking untimely questions about how we should live our lives and arguing over those answers is, in fact, what defines real life.

Philosophical inquiry itself, in other words, is both what makes up our lives and the very best thing we can do with them. It may be true, as Callard writes, that people often find that kind of intellectualism, especially in our age, so implausible as to be ready to dismiss it without serious consideration. But Callard, a self-described hard-line intellectualist, claims that the openness of Socratic intellectualism, its willingness to ask and ask and ask, provides an invaluable reprieve from our hardwired human need to already know, to be assured in our answers, even if we have not yet learned what questions need asking. Although we may not answer any of those questions tonight, we are lucky to watch two great philosophers ask them of each other.

Agnes Callard is an associate professor of philosophy at the University of Chicago. She received her MA in classics and her Ph.D. in philosophy at UC Berkeley. So we are also welcoming her home this evening. She is the author of Aspiration, The Agency of Becoming published by Oxford in 2018, as well as a 2024 chapbook entitled The Case Against Travel. An avowed public philosopher, she’s a frequent contributor to outlets such as The New Yorker, The Point, The New York Times, The Atlantic, Harper’s and the Boston Review.

Judith Butler is the author of foundational books in fields as wide-ranging as feminist theory, political philosophy, queer theory, psychoanalysis, literary theory, and cultural studies, not to mention their contributions to more public modes of discourse, most recently in the form of their book, Who’s Afraid of Gender? Worth noting in light of our event tonight is that Butler’s work, especially in the realm of political philosophy, makes frequent recourse to the culture and ideas of Ancient Greece as both object of and condition for their thought. Antigone in particular acts as a rebus through which we encounter Butler’s opinions on everything from Hegel, Lacan, kinship structures, sexual normativity to grievability and precarious life. Other essays and books have responded to the plays of Greek tragedians Aeschylus and Euripides, and on the philosophical side, to Aristotle, both in his own right and in concert with Foucault virtue and the meaning of critique.

Here at Berkeley, Butler is Distinguished Professor in the Graduate School and formerly the Maxine Elliot Chair in the Department of Comparative Literature and the founding director of the program in critical theory. One final note before I turn over the floor to our speakers for this evening, Professor Callard will be presenting another talk entitled, “Is There Any Such Thing As Socratic Irony?” tomorrow evening at 5 p.m. in 370 Dwinelle Hall sponsored by the Joint Program in Ancient Philosophy. So please do attend that as well, if you are able. Now, please join me in welcoming Agnes Callard and Judith Butler.

Judith Butler: Oh, it is on. I can hear it’s on-ness. Oh, welcome. Such a wonderful book. Moving, surprising, uplifting. I was so pleased to read it this summer and then to read it again in anticipation of our conversation here today. I thought I would just start by noting that you make the case in this book for something that you call open and critical inquiry, open thought, critical thought, thought that involves listening, refutation, conceding, and making space for reasonable disagreement. I’m wondering whether you had in mind, and it seems like you surely did, that Socrates has something to tell us about how intellectual life should proceed in the university, but also in our common life together.

Agnes Callard: Yes, in both cases. In general, I think the point of philosophy is to understand what you’re doing, and then you’ll do it better. I think that keeping Socrates in view, for me, often helps me see that there’s more space in a conversation than I thought there was. So it’s like there’s just a way that a conversation can go. It can almost somehow seem to be unfolding under its own weight. And keeping Socrates in the corner of your mind, maybe there’s a moment where there’s a question you could ask, where you can ask someone to explain something or justify something, where asking for that explanation or that justification, it pushes sometimes a little bit against the norms of the conversation. You might have this feeling, this might not go so well, or it might not feel so good, so there is something you’re pushing up against.

So I think yes, in the context of a university and also in the context of everyday life, I guess my thought was that there’s asking for explanations, trying to refute people is a good thing to do. It’s a nice thing to do to them, but it doesn’t always feel that way. But I think if you can get into view that it is a nice or good thing to do, that will actually change how you respond when people try to do it to you.

Judith Butler: And if someone says, “Oh, you’re refuting me, that’s very rude,” and would you be able to respond and say, “No, I’m actually being very nice?”

Agnes Callard: No one’s ever said that to me. I am looking forward to that day. It would be amazing because first of all, they would be acknowledging that I’m refuting them. So that’s already a huge success. And then this is an interesting question, have they been harmed? I was just translating the Alcibiades yesterday with my Greek translation group, and there’s a wonderful line, this is in the first Alcibiades, where Socrates is like, “Come on, come on answer.: And Alcibiades is like, “No, you just talk. I don’t want to answer.” And Socrates is like, “Answer.” And Alcibiades says, “OK, I guess I’ll answer because I don’t think I will be harmed.” And Socrates says, “You are a prophet.” That is, I can’t hurt you. And so it’s that realization that the worst thing that could possibly happen doesn’t actually hurt you, is incredibly freeing.

Judith Butler: It’s freeing, freeing of thought. And you write in this book, there are some autobiographical moments, and I appreciate the way you move between autobiography, scholarly discourse and public life and anecdotes from public life. You describe, I’m going to read in your voice, “When I was 21 years old, a senior in college, I tried to do it, to be Socrates. I lived in Chicago where the closest analog to the Athenian Agora are the steps in front of the Art Institute. So that’s where I went. When I got there, I walked up to the people milling around the front of the museum and asked them whether they wanted to have a philosophical conversation. When they said yes, and most of them did, somewhat to my surprise, I would follow up with a question such as, ‘What is art? What is courage? What is the meaning of life?’”

And you said that you were hoping that a fabulous dialogue would ensue, but what you found instead was that the conversations were all quite short and never really got off the ground. “The people I talked to seemed put off by my approach, confused about my intentions, and in truth, somewhat afraid of me. They felt trapped, and I felt not at all like Socrates.” So at one point in the book, you also say that this confrontation between the philosopher and the non-philosopher, however we might differentiate those two groups. And it might be difficult sometimes to differentiate those two groups. I don’t know. But that confrontation is a primal scene. Could you talk to us about that?

Agnes Callard: So I describe it that way in the context of the Meno, because in the Meno, Socrates is talking to this guy Meno, and he’s asking him to define virtue. And Meno tries, and then he fails, and then he tries, and then he fails, he tries again, fails again. And Meno’s like, “I’m really good at this thing, of making speeches, and you are just numbing my mouth so I can’t say any words. And actually now that I think about it, I just don’t think this thing is possible we’re trying to do. If you don’t know what you’re looking for, how are you ever going to even know when you’ve found it? And if you do know, you’ve already had it, so there’s no point to inquire.”

And he says, “You,” the way Meno puts it like, “If you don’t know what you’re looking for, how will you find it? And if you already do, there’s no point to inquire.” And Meno wants a proof. He wants Socrates to show him that this philosophy thing can actually get you somewhere, can make progress. And I think that there’s often this experience in philosophy where the non-philosopher wants, without actually ever doing philosophy, to be shown that philosophy is going to get them somewhere. Before I stick my foot in the pool, just show me that it works. Show me that this system will move me forward in thought before I decide that I’m going to participate.

And there’s a problem with that because you can’t do it, that is the person who has to make progress is you. And if you’re not going to participate, you’re not going to make the progress. So Socrates compromises, and he does a mathematical demonstration instead of a philosophical one just to show him, “Look, a person can make progress,” and he does it with a slave. Maybe I’ll say one more thing about this conflict. The way that it comes out in the Meno chapter is as a distinction between questions and problems. So what I say is that we’re all familiar with problems. A problem is something when there’s an obstacle in the way of your proceeding. The word problem is the Greek version of the word obstacle, basically. And when you have a problem, what you want to do is keep doing the thing that you were doing before the problem arose with doing it and get that obstacle out of your way and keep going. A problem is something you want to remove or dissolve.

And a question is something very different. It comes from quaerere, to seek or to hunt, like you’re on a quest. And when you have a question, there’s something that you want. There’s something you want to get. At the end, you’ll have that thing. It’s not you’re trying to get it out of the way. It’s the thing you want. So I think often when non-philosophers are looking at philosophy from the outside, they’re like, “What problem is it going to solve?” That is what is there which is an obstacle to what I already wanted to do, where you can take that away and then I’ll be able to keep doing what I independently wanted to do, which had nothing to do with philosophy, better because the philosophy will take the problem away? Show me that philosophy works in accordance with that formula.

And Socrates has to say, “I can’t show you that because actually philosophy is answers to questions. And so what is it that you want to know? We can try to figure that out.” So that’s another element of the primal scene is getting the other person to replace their problem. conception of philosophy with a question conception.

Judith Butler: So I recently had the experience of, I think I must have been talking about the good life or a precarious life or something, and the interviewer said, “Oh, don’t you need to define your terms. What is life? What is precarious? Can you define your terms? And then we can talk about it.” And of course, one has to stop them because the whole point of the question is to open up an inquiry in which we might discover along the way what these terms mean. And we would do it through a method that considered alternatives sent, provided reasons in light of possible objections. And at one point you cite Kleist, and you found, I think in Kleist, a very interesting description of writing or speaking where thought itself is fabricated through speech or it comes to be known in the course of the dialogue itself. And does that process explain further why it is you prefer questions rather than problems, or why you think philosophy ought to be concerned with questions rather than problems?

Agnes Callard: I think questions are what drive the enterprise. Of course, there are problems too.

Judith Butler: Like funding.

Agnes Callard: Exactly. So the Kleist line, it’s an essay called On the Gradual Construction of Thoughts and Speech. And what he notices is that a lot of times if he just can’t think of anything, if he’s just stuck in his thought, what he has to do is look at his sister’s face, and then the words will come out of his mouth. And it’s like, “How has this magic happened, that a human face draws words out of my mouth?” And he says, “What’s especially great is if it looks like she’s about to talk, because then I’ve got to quickly say something to stop it so that I can say my thoughts.” And that brings out also the limits of Kleist’s point. So Kleist just thinks, look, you need an audience, and you might even think of it, he’s a playwright, as though for him life is something that he’s performing for an audience.

And what I say is that there’s something Kleist is getting right there about the relationship between thought and the social, but that Socrates has a better grip on it when in the Alcibiades he says, “I’m not saying thoughts to your face, Alcibiades. I’m not saying words to your face. I’m not talking to your face. I’m talking to your soul,” which is to say you get to talk back. So I think the question about questions versus problems, it really does hinge on the ability to talk back because in an inquiry you need an answerer. And in my book, I argue that inquiry is conversational, and it has a particular structure. There needs to be a question, or there needs to be an answer. The answerer needs to be able to talk. And so Kleist’s model gives you a sense of why we might need other people, but he doesn’t quite give you the full breadth of it.

Judith Butler: Right. There is, I think, one point where you actually say, “Thinking is social.” Is that true of an interior monologue?

Agnes Callard: So …

Judith Butler: Lacan would say yes, by the way.

Agnes Callard: So I think its depends on the monologue. So if you’re talking about the monologues that happen in my head when I’m wandering around, I think it’s just very close to dreams. It’s nonsense thoughts, things just popping one thing and then another thing, and it’s not at all … When I am alone and have thoughts going through my head, it’s nothing like Shakespeare. It’s just not organized. And so I think that if what you mean by monologue is a monologue in a play or a monologue where it’s already expressed in language, then yeah, absolutely. But there is the other kind, maybe it’s the kind that say someone like Joyce is trying to capture in a stream of consciousness narrative. But even there, there’s so much more coherence to that than to at least what happens in my head.

Judith Butler: But this probably takes you to another zone, but in Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, for instance, he does talk about dream thoughts, and he thinks they are organized, that there are some rules, condensation, displacement, like that. And so you could analyze the syntax of a dream and even a dream thought, and it would be jumbled or condensed, but it could be laid out in some kind of propositional form. Maybe you’d lose something, but at least for a thought that dream thoughts were there.

Agnes Callard: I have a couple thoughts about that. That’s a super interesting point. So one is, but how important is it to the idea that dreams are thoughts and that they have an intelligibility that we can analyze them? There’s a laying out process which is done in analysis. But also it’s like the nature of the dream thought. When we say things like, well, “There’s no negation in the dream.” So negation doesn’t show up, but negation does show up in our thoughts. I can say not. I can say there’s no negation in dream thought. That’s a waking thought. And it’s like in noticing that, noticing that negation is, in a way, missing, what I’m doing is I’m saying, “Well, dream thinking is a funny and approximate version of this other kind of thinking where it has to be understood in the light of it.”

And so I think that what I want to commit myself to in the book is that the paradigm case of thinking is going to be conversational. It’s thinking about certain kinds of questions, certain kinds of fundamental questions, because we have blind spots, and we need other people to show us as blind spots. But first, even before we get to monologues or Freud, we can just talk about, I actually think philosophical training, the kind of training I got here as a grad student in the philosophy department, is in large part just a training of how you internalize that. You imagine how people are going to try to refute you, and then you’re like, “I’m giving a talk tomorrow on Socratic irony, and I’m imagining how John is going to try to refute me.” And I’m like, “What’s he going to say when I say this? Well, let me anticipate that and put that in the talk.”

And that’s how we give talks is we imagine our audience, we channel them, and we have, in effect, a little monologue with them. But then you go and give the talk, and this is the amazing thing. To me I’m still astonished by it every time it happens, because I’ve spent all this time doing that, doing the monologue and armoring my talk against objections. And then I give the talk, and then the hands go up immediately. That even doesn’t even take any time. And there’s just things I didn’t think of. And I was channeling the audience. Why didn’t I think of that? And it’s because even with training and with all this time and with all this effort into it, you just do have these blind spots, and it’s an imperfect version of another thing.

Judith Butler: I’m just wondering, I don’t want to belabor this too much, but I have two questions. One is, could we say that even our internal thinking, what we call that, is in some sense dialogic in structure? Because you have introduced the idea that thinking is conversational. So could we say that we think with ourselves, that we partner with ourselves in thought? And then the second is a larger question, which is-

The second is a larger question, which is, you chose not to write a book on Plato’s dialogues. You wrote a book on Socrates. So, do you have a Plato-Socrates distinction that you’d like to talk about?

Agnes Callard: My husband says that for me Plato is Socrates in ugly clothing. That’s not totally fair. But I just thought I would admit that to you guys. Plato’s what I’m always trying to peel away to get to Socrates. Well, maybe I’ll say more about Plato in a sec, but I’m so interested in the … Plato says the thing. I mean, in the Sophist, in the Theaetetus, that thinking is the soul having a conversation with itself.

Judith Butler: Yes.

Agnes Callard: So again, that’s Plato, Sophist and Theaetetus. I think that, yes, but that there’s a real difference between, say, the stream of consciousness garbage that goes through my head when I’m just wandering around, and maybe I’m an extreme case, I just really have trouble thinking by myself. That’s not really a thing I can … To a degree that I think would shock many of you if you really knew how true that was. But I’m pretty much, if I’m thinking, I’m reading, I’m writing, or I’m talking to someone.

Judith Butler: It’s funny, we do doubt you, but we’re going to give you the benefit of the doubt. OK.

Agnes Callard: So there’s just that mush. And that’s really different from if I’m trying to work through an argument. And so having a dialogue with myself is not just a paraphrase that I would use for any time when any representations are fleeting through my mind. There’s a specific thing. And I think what I’m doing in the times when I really am “having a dialogue with myself,” is that I’m simulating another person, and I’m imagining them holding me to standards, which is exactly what I’m not doing when the mush is going through my head.

Judith Butler: Right. But when we think about Plato’s dialogues, there are all kinds of features to those dialogues that are not just the conversations that Socrates is having. We get descriptions of characters, somebody belches, or the women have to leave the room at a certain point. There are all kinds of other things that are happening in the scene. And I’m wondering whether it’s important for you to background those dimensions of the dialogue in order to foreground Socratic conversation.

Agnes Callard: I think … I do, as a matter of fact, background them. So let’s just be straight about that. Not always. There’s a few of them I pick up on. So, at the end of the day, I think the most interesting things in the dialogues are the arguments in them. The argument against weakness of the will, the argument that doing injustice is worse than suffering it, the argument that love is a kind of madness. To me, that would be what I first and foremost take away. A lot of them are on my pants today. I mean, the conclusions, not the whole argument. But I do take it to be significant that the presentations of these arguments are personified.

People like reading Plato’s dialogues, even first-year students in a intro philosophy class, or I teach a kind of humanities core class, and there’s a way in which they find the dialogues gripping, where they would not find an abstract presentation of those same arguments gripping. And I think this is something I don’t feel I have a real handle on, but people like philosophy to come packaged with people. People, I’m a public philosopher, and people want to know about me. And they’re like, “We don’t just want your ideas, we want to know how your ideas are ingrown into you. And we want that package.” And that’s true for me too with Socrates, right? Maybe there’s some details of the dialogues or whatever, I’m not paying attention, but I’m paying a lot of attention to Socrates and to who he is as a person.

So, I think there’s something important about that packaging, even though I have trouble reconciling it with some passages. At the end of the Euthydemus, Socrates says to Crito, “Pay no attention to the practitioners of philosophy, whether good or bad, but just pay attention to the thing itself, whether their philosophy itself is good. And if it is important, then dedicate your whole soul to it.” Because Crito’s like, “These guys, Euthydemus and Dionysus, these people who we just listen to talk, they’re charlatans. How can you pay attention to them?” And Socrates is like, “That doesn’t matter. Don’t worry about the people, worry about the activity.” But we do worry about the people.

Judith Butler: But if we’re to dedicate our whole life to it, and become philosophers, and live a philosophical life, then the person is implicated in philosophy necessarily. So, we couldn’t account for that. Where would that passion come from? Whose passion would it be? So it does seem to me that your own position, which is extremely concerned with ethical questions, the right way to live, the good life, the right way to treat other people, you have an overarching concern, as did Socrates, not to cause harm. So, there’s a practical and ethical dimension to your own staging of philosophy, which foregrounds ethics say over metaphysics, which might suggest one reason why you’re preferring Socrates to the ugly clothing guy. And my ugly clothing anyway. Why would you call Plato ugly?

Agnes Callard: Well, I mean, maybe beautiful clothing would be the better phrase, but the point being that I’m always just trying to access Socrates, and my access to him is through Plato, right? So it’s like …

Judith Butler: Yeah, you got to go through his gate.

Agnes Callard: Exactly.

Judith Butler: I see.

Agnes Callard: But yeah, the point about not causing harm, I think it’s a really good one because I’ve been having a bunch of conversations with someone that I do a podcast with, and he keeps trying to turn my book into an advice book, and he’s like, “So, you’re telling people to do 10% more philosophy every day?” “Is it that if the philosophers of the past had used your method, then we would have 50% more philosophical truths today?” Or, “What’s your actual claim here?” And I’ve noticed how uncomfortable I feel when he tries to turn, when I’m asked, when I’m put in a position where it’s like, “Tell us what to do.” I don’t feel like I can tell people what to do.

And it’s not just because, well, they might do it and then that might screw up their life and then they might blame me, it’s that actually I don’t know what they should do. And I feel the Socratic humility, it’s also a kind of protection against causing harm, that is, when Socrates is like, “I don’t actually know what you guys should all do,” what he’s saying is, “I’m not presenting myself as a teacher who can just give you things, and then you can do those things. You have to hear what I’m saying in an inquisitive spirit. You can challenge it, you can ask about it, we can have a conversation. That’s the kind of thing I’m saying.” And I just noticed how uncomfortable I get when my interlocutor doesn’t want to hear what I’m saying in an inquisitive spirit and wants me to just give out advice and not ask me about it, because then I’m like, “Wait, I’m now in a position where I could cause harm.”

Judith Butler: Thank you. That was really helpful. There’s another discussion in this book about kinship, which kind of interested me. And I think it’s chapter three, and you’re discussing commands, and I believe you say that commands are felt as pain. And then it seems as if kinship is defined as a set of relations in which a set of commands are being implicitly communicated, because how you’re supposed to conduct yourself within the norms of kinship are determined by your position in a kinship system or set of relations. So, if you are a mother, you are commanded to act this way; if you are a child, you’re commanded to act this way. But I’m wondering whether you have taken a traditional idea of kinship as the basis for your claims here. Can you imagine kinship in which that would not be the case?

Agnes Callard: Yes. So, the first thing to say is that the English word kinship is not a great word for the thing that I’m talking about, unfortunately. I’m talking about filia in Greek, but there is no English word that perfectly fits that. It’s like the set of connections we have to other people. But it could be to members of your family, it could be to members of your city, it could be to any group that you belong to. Your people, the people who you would say “are mine.” And I say the English word kinship covers just a narrow part of that, and I’m just stretching it to cover everything under filia because I don’t have … But another Greek word, for people who know Greek, that this is the domain of thumos. So, in The Republic, Plato divides a soul into three parts. An appetitive part, epithumia; and then the middle part of your soul that is the part that gets angry, it’s the part that feels bonds with people, the thumos. And then there’s the top part, the reason part. OK.

So this set of bonds is the province of that middle part of your soul. That’s another way I could have defined it, but there’s still no, thumos is not a great word to translate into English either.

Judith Butler: But I’m wondering how to make this part of your position more contemporary. I’m thinking about the family fight. And you yourself give some examples of parents and children, or how they communicate, and how not to make it into strict obedience, or how to respect the other in their wish and even in their resistance. So, it seemed to me that some of your familial, and maybe here I’m confusing categories because of the filia problem, but some of the familial instances have a lot of antagonism, and a lot of confusion, and a lot of inquiry, like, “What is it you wish?” “Who are you?” Rather than a command that immediately puts everybody in their place, and governs their conduct in an unequivocal way.

Agnes Callard: OK. Can I give a slightly long answer to this?

Judith Butler: Yeah, why not? We’re here to listen to you.

Agnes Callard: So, the beginning part of my book argues that when we are trying to go through our lives, we’re assuming answers to questions about how to live, before we ask the questions. We somehow start with answers. And that’s weird. Where did we get these answers that we just start with, for free, without inquiring? And what I say is that there are two sources where we get “free answers” that is answers to questions that we haven’t asked. One of them is our bodies. So we feel pleasure, and pain, and hunger, etc, and we just get that for free. Kind of when you’re born, you’re like, “I have to eat.” That’s an answer to the question of what should I do. I should eat.

And the other is other people. So, when I look out at you guys and the expressions you have on your faces are pretty similar to each other, that is, you know how you’re supposed to hold your face in this kind of context. You’re not supposed to sit with your back to me, you’re sitting up. There’s a way to be in this context, and you’re doing that. You’re following the rules for the group that you’re in. We all do that incredibly well. So much of the time, we don’t have to fight it. We just swim right along, in the same way as eating when you’re hungry. I call these commands because they are answers to the question, “What should I do?” When you haven’t asked the question, and that’s what a command is.

If I’m like, “Everybody jump,” you didn’t ask me what you should do, and I told you anyway, I commanded you. So, what I say is that these two sources of answers, they both have problems. The appetitive one, it has a problem of time consistency. Our bodies are like, “Eat another cookie, eat another cookie.” Oh, no, you shouldn’t eat an extra cookie. And the familiar one has the problem of revenge. And of taking our kin, our philoi, and suddenly they become an ehteroi enemies. It’s really only your philoi that can become your ehteroi.

Judith Butler: OK. OK. This is important.

Agnes Callard: And what I say in terms of, I kind of map out the history of philosophy, a history of ethics, along these two commands. And what I say is that sort of the Epicureans were the people who took up that bodily command and systematized it, and made it time consistent by introducing something like hedonic calculus. Eventually that gets taken up in the 19th century by Mill, and also Bentham and Sidgwick, into utilitarianism. It gets further systematized.

The kinship command, as I call it, is picked up by the Stoics. And the Stoics are like, “Look, we’re going to subtract the whole anger and revenge part, and we’re going to talk about the group that you’re a part of as in a way you’re a citizen of the cosmos.” And that gets further developed and refined in 18th century by Kant. You are a member of the kingdom of ends, of beings that can legislate for themselves. That’s high class kinship. Both of these traditions are further, there’s further even more contemporary versions of them, constructivism or consequentialism, right? OK.

So, these are very deep sources of motivation that we struggle with. And we struggle with them because they mislead us. They order us around in ways that are obviously bad for us. And so then we try to take thought and stick thought on them to make them go better. And to a large degree, we’ve succeeded. Those are big improvements. The things I described are big improvements. OK.

But there’s a question I don’t talk about in the book. I had to say all this to get to this interesting part about, doesn’t kinship open itself up to argument? Because I think yes, OK, it’s like secret doctrine, it’s not in the book. In the book, I’m very egalitarian between the utilitarian and the Kantian lines of thought. But there is just a kind of sort of fundamental difference between your kin and your body, which is that your body is not going to talk back to you, ever. Your body is not amenable to argument. It’s not going to ever accept, “No, I really shouldn’t eat now, just stop making me feel hungry.” You just keep feeling hungry. You can argue forever.

Whereas your kin, it looks like those relationships can be, as I say in the book, sort of Socratized, that is you can, instead of just say, “Well, maybe we shouldn’t do things this way,” “Maybe we shouldn’t have this expression on our faces,” we can make the case. And so I do think this is me tipping the scales in favor of Kant over Mill, in a way that I don’t do in the book, that I do think that the kinship command more lends itself to inquiry than the bodily command.

Judith Butler: I see. OK. This raises another question for me. You say in the book that you’re offering a philosophy of emotions, for instance. But you do along the way talk about sadness, anger, revenge, love, a bit of hatred. I wonder if it’s fair to ask you whether you understand Socratic method, or perhaps the dialogues, to be the source of a philosophy of emotion. Or maybe you wouldn’t separate off philosophy of emotion from some of the other issues that you’re pursuing.

Agnes Callard: It’s a great question, and I’m pausing only because I don’t have a ready answer to it. That is, it’s like what I’ve done in the book, there’s a moment where I’ll just get super interested in how is sadness different from anger. It’s funny because somebody, I saw a tweet the other day, she’s like, “How could anyone ever ask that question? It’s so obvious.” I’m like, “It’s so hard. It’s so hard to analyze how sadness and anger differ.” I’ve spent years on that question. But I’ll just get pulled into it, into question. And I think there’s a philosophical, that is, in a way, the difference, what I sort of say in the book, though, I don’t develop this as much as I would’ve liked, is it’s kind of the difference between the bodily command and the kinship command, is kind of the difference between sadness and anger. But what I don’t do is pull all these various observations about emotion together into the category the philosophy of emotion.

And I think I find it really, really hard to tackle the topic of emotion as a topic, as that kind of, as a cogenus. What’s a really bizarrely good treatment of it is, at the end, the unpublished part of The Man Without Qualities, Robert Musil’s modernist novel, it’s this novel about this guy who’s secretly a philosopher, but he won’t ever do philosophy. But at the end, he’s starts producing a treatise on the emotions. And I was like, “Oh, this is the closest thing where it’s about how emotions are a form of aliveness.” OK, maybe we should say, “Well, Nietzsche too,” or something, would be just as good on this. But the thing you would be deprived of if you didn’t have emotions is you would just not feel totally awake to the world, or totally alive to the world. And that’s what a general theory of emotion would articulate that, would articulate the emotion as a form of aliveness. And I just don’t think I give you any way of doing that in my book.

Judith Butler: OK. But here’s a suggestion, because your first book was on aspiration. And here there are several examples you give when people are trying to become a certain way, or when people are trying to achieve knowledge. There seems to be a kind of striving for the good, or for the true, or for the just, that you see in Socratic questioning. And I’m wondering whether that aspirational framework would be the one in which you would situate emotions.

Agnes Callard: So, one way to do it would be to say, an emotion is the thin edge of some wedge, where when that thought fully gets articulated and expressed, it’s going to not be in an emotional form. And that might be how an intellectualist like me should think about emotion. And then, yeah, so the thing you’re saying would fit with that, that we have to give the theory of emotion in the context of aspiration, where the emotion might be your first attunement, or first inkling, of a certain thought that you develop better.

And definitely, maybe there’s only one part in my book where I talk about Antigone, which is the Creon telling that guard, “I’m going to teach you a lesson,” where my thought is like, he’s really angry, and there’s this guard who didn’t actually bury Polynices, but Creon thinks that maybe he got paid to do it. And Creon’s like, “I’m going to hang you, I’m going to torture you, I’m going to teach you a lesson. You’re going to learn.” But he’s angry, but the thing he’s saying has a kind of truth. He wants to teach this person, he wants to educate them. And so you might say, in that emotion is the beginnings of a thought, that if he could develop it, he would move towards Socrates.

Judith Butler: OK, that’s great. Thank you. So, I had a question, two sort of final questions, and then we can open it up. Does that seem appropriate?

Agnes Callard: Seems great.

Judith Butler: One is, well, you note that when students first read the dialogues, they sometimes are angry at Socrates. They think he’s a bully. Or they think he’s trying to vanquish his interlocutor, or humiliate, or win. And Alcibiades, of course, accuses him of trying to win. And you take issue with that. But sometimes it’s hard, because it seems as if Socrates holds the knowledge, and doles it out bit by bit through humiliating lessons. But other times it seems, as you describe, that something gets elaborated through the conversations, through the positing and refutation, something gets elaborated along the way. And it is collaboratively wrought, as it were or discovered that would be better. So I’m just wondering, what is your argument against those who think Socrates has a sadistic streak?

Agnes Callard: So I mean, I think the Alcibiades example is great because he’s accusing Socrates of trying to win at love. That is, “Oh, you’re just trying to make everyone fall in love with you, and then you want to make sure you don’t love them.” He’s inflated this to the whole, into the romantic dimension. “You’re not trying to just beat us in argument, you’re trying to beat us in love.”

Judith Butler: Yeah.

Agnes Callard: And the way that Alcibiades understands that is that he imagines Socrates as a statue that has other beautiful statues inside of him that he hides from everybody. He hides his precious wisdom, and he won’t share it with people. Keeps it to himself. “But I, Alcibiades, got to have a glimpse of it, unlike the rest of you, people.” So Alcibiades feels privileged. He feels like, “You should listen to me about Socrates because got to look inside and see the wisdom that he keeps hidden.”

So, I think that there’s something really deep about that inclination that we have to think that Socrates is hiding something from us, and that deep down he has some wisdom that he is holding in reserve, but …

… some wisdom that he is holding in reserve, but of course he could provide it if need be. I think that maybe, I’m not sure, OK, what is it about that image that’s so appealing or important? I think that we don’t really want to accept how desperate Socrates is, that he’s kind of an ignorant man throwing himself at the feet of the people around him, that that’s who this guy was, who we’re all admiring and looking up to. Didn’t he know he actually really know. And no matter how many times he’s like, “Actually, I don’t know.” Yeah, but that was ironic.

Actually, secretly, deep down somewhere, you’ve got this thing that is the reason why we admire you so much. We’re going to have to project it into you. And now once we’ve done that, once we’ve projected it into you to make ourselves feel OK about how much we admire you, because actually you do have something special in you hidden. Now we’re like, “Why aren’t you giving it to us? You’re a jerk. You’re kind of a bully and you are just humiliating us instead of just telling us your lesson.” So I feel like the jerk bully humiliating lessons is a consequence of the earlier thing, which is the projection of this special secret hidden knowledge that we need Socrates to have because it’s see ourselves as admiring and imitating this kind of desperate man.

Judith Butler: Desperate, kind of lost and seeking. Yes.

Agnes Callard: Yeah, and very beggars can’t be choosers. It’s like, I’ll do what I need to do to make you talk to me because otherwise I can’t get anywhere.

Judith Butler: Well its interesting that you, toward the end, take issue with the Gregory Vlastos interpretation of the Platonic Dialogues as full of a positive irony. And you yourself say that when you first started reading the dialogues, you thought, “Oh, they’re ironic,” and you wanted to have clever, sophisticated readings and decode them in certain ways. I don’t know if you accepted the ironic structure, but …

Agnes Callard: I did.

Judith Butler: … there was some doubling going on. But you have developed a very strong rejoinder to the Vlastos position because if I read you correctly, what the ironic interpretation misses is what you call Socrates, the naked vulnerability of Socrates. And that this vulnerability you say is displayed in treating others as sources of answers to his questions. So he is appealing to others even though he’s like, “Tell me what is virtue? Tell me what is beauty? Tell me what is justice?” And he’s appealing, I think you would say, from vulnerability or even need to know and exposing that need to know publicly. These are not just hidden sequestered conversations. These are public conversations.

And the other with whom he’s speaking or to whom he’s appealing or whose answers he’s soliciting, is the very source of the answer to his questions. He trusts that the answer to his questions are in the other. And that strikes me as a very different kind of way of understanding the sociality. And there’s another moment where you say, you know if we look carefully at these conversations, there’s a principle of equality going on, not domination. And you also suggest there’s a principle of freedom at play. People can respond in all kinds of ways. He can readjust his questions in all kinds of ways and people have to arrive freely at whatever conclusion turns out to be the case. I don’t know if you could talk more about that. It was very moving, interesting, and I think very possibly an original way of thinking about what’s happening with Socrates.

Agnes Callard: Thank you. Yes. So the first thing I’ll say is that I’m going to talk a lot more about this tomorrow. So if you’re interested to come to the event tomorrow. And second thing I’m going to say is that I think there are some compelling alternative ways of looking at Socrates. One of them is a paper that John Ferrari wrote, and I’m going to talk a little bit about that paper tomorrow. So I think that there’s a case against my case. Let me just admit that and I’m going to try to make the case against that case tomorrow. But I actually want to go back to a thing you said a little bit earlier, the sort of collaboratively raw part. Because I think that maybe the thing that sounds hard to believe in what I’m saying is that it’s like, look, here’s what never happens in the Socratic dialogue.

Socrates goes up to some guy and he’s like, “What is virtue?” And the guy gives me answers. Socrates is like, “Great, thanks.” That never happens. And it sort of looks like what Socrates does is pushes and prods until he gets at Socrates’ answers. And people have often that strong feeling like, “Well, this is really Socrates views.” Now, I think it’s just that Socrates has had a lot of these conversations. And so his views have become refined over the course of many conversations. And he knows where a conversation on, for instance, the question of whether it’s better to do justice or suffer it goes, because he’s gone there a lot of times. And now after he’s done it so many times, he can say something like, “Look, these conclusions are tied down by arguments of iron adamant,” which is not to say that they’re not still open to questioning. They are.

So the point is that I think that it’s absolutely, it is a collaborative project, but the reason why it can look as though Socrates is sort of doing all the work, is that Socrates questions have behind them, so many other collaborative conversations and typically his interlocutors don’t. But the wisdom or whatever we see in all those conclusions, that’s just what Socrates caught to from conversation. That’s all that is. Yeah, so I think what I say in the book is that two of our big political ideals are liberty and freedom and equality. And a lot of times people think those conflict with each other. And I’m specifically interested in freedom of speech as I make the case that freedom is freedom of speech. So freedom of speech and equality. And if you kind of interpret those values from a Socratic lens, they actually turn out to be the same value.

Namely, speech is free when it’s inquisitive. And what it is for speech to be inquisitive is that you’re talking to someone, and here’s how Socrates puts it in the Gorgias, that’s one of my favorite lines. He says to Polus, “I’m calling for a vote from one man alone.” That is, look, there might be all these people listening to us. I don’t care what they think. I’ve made my case when you agree with me and you’ve made your case when I agree with you, and that’s equality. That is, it’s that your mind is on par with mine for pursuing this argument.

I don’t get to hold myself in reserve and be like, “Yeah, but I still know that I’m right, even though Polus wouldn’t agree with me.” That’s what Socrates won’t let himself do. And so I think actually a lot of time when we make room for disagreement in conversation, it’s very unsocratic, because it’s like, “Oh, well look, this is just my opinion,” and so I’m allowed to have an opinion that you don’t agree with. Socrates is like, “I’m not allowed that. We’ll know what my opinion is at the end of this conversation when you agree with it, or maybe I’ll have changed it and then it’ll turn out that that’s my opinion.”

Right, so that is what I see as Socrates’ vulnerability or openness, which is to say, he really is trying to think with someone else. He’s not saying, “Well, I have some thoughts and then I shoot them out and present them to the other person and they can do some stuff with them, but I can still go home with my thoughts. I can take my ball and go home anytime.” That’s not how he’s thinking about it. And I guess I think on pretty much any view of Socratic irony, there is a way in which Socrates holds himself in reserve, that is intention with the way that I read Socrates.

Judith Butler: So I just want to finally note the title, Open Socrates, and then the subtitle, The Case For a Philosophical Life. So Open Socrates, you just said, you’re making the case that Socrates is open, vulnerable, that this is a different way of seeing him than has been generally received, or maybe first impressions don’t always include openness …

Agnes Callard: I’m sorry, I have to interrupt you for a second, just to tell you the first person to understand the title, because I’ve gotten like, “Is it Open Sesame? Is it like Open AI?” But yes …

Judith Butler: You just used the word open. So I was just listening carefully and transposing here. But Open Socrates also, it struck me that you’re opening Socrates to a broader public. And I mean tomorrow I presume you’ll have classicists and philosophers, but today we have different people from different fields and possibly outside the academy. And you’re opening Socrates and you’re writing things in the public press and you’re bringing him into public life and in fact, making a case for certain kinds of conversations that don’t shut down too quickly or that make room for reasonable disagreement. Which brings me back to the original point that you’re modeling something, I don’t know if that’s the right word. You’re calling for something and maybe enacting a certain way of thinking about conversation or public conversation, which is why I’m so happy to be in conversation with you.

So there’s that. But then also the case for a philosophical life. It is true, you talk throughout the book about what it is to lead a philosophical life and the difficulty of doing that. But one thing that seems clear to me and tell me if I’m pretty sure you’ll agree, and what I say won’t be right unless you agree, is that the philosophical life is lived together, yeah? It’s a collaborative or shared life. So it’s not a fully individualistic phenomenon, even though it always implicates the individual in decisions and actions, et cetera. But it can’t be lived without others or it can only be lived with others.

Agnes Callard: Yeah, I agree to all of that, and I think that I’ve been a kind of proto-philosopher, at least since high school. But it’s I feel that I keep asking myself a question, is this for real? Do I really mean this? And one way that that manifests is, how loud can I say it? It’s like, I can do it with my friends, I can have philosophy conversations, but in a classroom I better make a good showing or something. Or maybe I can do it in the classroom too. Maybe can I do it in the New York Times? But I’m asking, I’m sort of experiment. So it’s like, yes, maybe I’m a model, but from my point of view, it’s kind of experiment of does this actually work where I can’t figure out whether it works unless I try to do it.

It’s partly that story that you read about the Art Institute. It’s like, can I do this in a way where I don’t scare people away? The answer isn’t there in advance. I’m finding the answer as I’m doing it. And one reason why maybe I feel a bit compelled to do it is the second thing you mentioned, which is that, it’s I can’t live a philosophical life unless all of you guys also commit. I kind of think we all need to commit, everyone, because then it’s always in our space of interaction to engage in that philosophical way. And so it’s a little bit how literacy doesn’t really work unless you get a lot of literacy. Who are you writing for if other people can’t read? And so I think that the same thing is true of a certain kind of conceptual or philosophical literacy that we want to all be able to engage with one another in that mode, that fundamentally, it’s not a private mode.

Judith Butler: OK. Thank you so much.

Agnes Callard: Thank you.

Moderator: So it’s silly to ask, are you open to questions? Are the lights all the way up? I think we have a mic.

Agnes Callard: OK, so everyone who asks the question gets a sticker, so just come up to me at the end. I have stickers for you. So questions.

Audience 1: Yeah, so I was wondering that any given conversation between interlocutors on a particular topic, let’s say the good. How much importance would you place on one aspect, the existence of a right answer? And two, whether or not the interlocutors actually believe there’s a right answer? And as a follow-up, do these answers depend on what the topic of conversation is at hand?

Agnes Callard: So, I think here’s a restricted thing that I think is necessary. You have to believe that you can make progress. OK. Now, does that mean that there has to be only one right answer? I guess I just think for many questions that’s not the case, that there’s only one right answer. There may be multiple right answers, but that’s not to say that any answer is equally right. Those are very different situations. And so I think that what’s necessary for the conversation is that there be sort of sustained in the conversation, a shared faith that we’re getting more in the direction of right as we’re talking about this. Is that equivalent to each party has a belief that there’s a right answer? I think it’s not really.

So one thing I share with Socrates is an extreme skepticism about the stability of this state called belief. That is, I think the thing I was describing about my mushy thoughts. That’s how I think a lot of people are. We think one thing, we think another thing. We often, in certain very special contexts, we express our beliefs in very passionate ways. And because somehow we index on those as what beliefs are, we’re not really getting how flexible and variable our beliefs are. And so I want to say, I don’t care that much about belief, but what it does matter is, are you engaging with another person in a way where that kind of shared project of coming to an improved answer, is sort of manifest in the virtues of the way that you connect the conversation? Are you listening to their answers? Are you asking them challenging questions?

If you’re doing all of that, that in some sense manifest or practices or exercises, something like a faith that you can make progress. But could there be moments where you’re like, “Ah, there’s no answer to this question.” Or moments where you lose, that’s fine, I think that happens. It kind of can’t but happen, I think over the course of life, it’s very hard to sustain a belief that there was definitely a right answer, but you can sustain the activity more easily. I don’t know if you have thoughts about that.

Judith Butler: No, but I think perhaps if you start with skepticism, that’s fine. Because at least in the Socratic conversations, many people do start with skepticism that can’t be defined or justice is whatever the powerful say it is, or we can’t define that. What are you doing or we already know. So you don’t have to start with belief in the sense of a certain belief, but your skepticism has to be open to being undone.

Audience 2: Hi. I can stand if that’s easier.

Agnes Callard: Thank you.

Audience 2: I’m thinking about when Socrates takes up a line of inquiry toward Meno and Meno experiences it as a kind of paralysis, as a kind of rest, as if having been numbed by an electric eel or a numb fish. That in that instance, inquiry is a kind of arrest that enables subsequent inquiry and opens up other kinds of thought. And I was wondering if you had much to say about a strategy of just asking questions that might actually work to arrest thought altogether rather than enable other lines of inquiry.

Agnes Callard: Yeah, I think that that is something that can happen for sure. That is, you can shut people up with questions and that can be a thing that people sometimes try to do. And if your goal is to show that they’re idiots or that you’re smarter than they are or that they, to discredit them in some way, that activity might make sense. But if your goal is to find things out for them, then that activity doesn’t make any sense. You never want to shut them down, right? Because it’s like you’re the desperate person. You need them to talk.

And so I think that it’s absolutely right that that could happen. If you’re a Socratic, you’re trying to prevent it from happening. It does happen in the Meno. And what Socrates does is he tries to show Meno, “Look, I didn’t actually hurt you. Let me do what I did to you, to someone else. I’m going to have you watch it. When he very confidently answered that he could find the side of the double square, and he did that once and he’d get it wrong. And when I arrested him and I made him feel like he couldn’t make confident speeches about that, did I hurt him?” And Meno’s like, “No, actually you didn’t hurt him by doing that.” And that’s how Socrates repairs. He sort of repairs that arrest. And he’s motivated to do that because he just wants more from Meno. But if he didn’t, if all he wanted to do was make Meno look bad, he could have just stopped at the numbing part.

Audience 3: OK, so my question is about writing and the written word. And so at one point you mentioned thinking in conversation with a book or reading something, like I’m thinking while I’m reading. On the other hand, you also mentioned the special value of face-to-face conversation and a live conversation partner. And then I guess just to channel Plato from the Phaedras, there’s that critique of writing in there where he seems quite skeptical about. Or there’s a real concern about writing as opposed to a live speaker. So I’m wondering what do you make of that passage? And then what do you think the value of the written word is? And then also I was thinking that written words on the one hand can be philosophical books, but also we have texts, text messages, tweets, emojis. So what do you think about all that? Thanks.

Agnes Callard: OK, I’m going to give you my answer, but then I’m also going to ask Judith for their answer because, so I’ll tell you that you’ve hit on a sore spot. The acknowledgements of my book are, I wrote in negative acknowledgements. All the people I blame for not helping me more with this book. Some people in this room are included in there. I’m not going to name names. And the problem that I wanted to solve, but I never solved in the whole book is this problem. I started the book, the way I started writing it was like, I’ll just knock this problem off in the introduction and then I’ll go off and write the rest of the book. And I spent a year knocking that problem off, writing and rewriting versions of an answer to your question. And my answers were just all terrible.

And I’m like, “You know what? I’m just going to put this on pause. I’ll write the book, and then as I write it, the answer will come to me.” So I wrote the whole book and the answer never came to me. And so then I just had to write an acknowledgements in which I’m like, “I never answered this question. It’s a really big problem for this book. Here are all the people who are partly responsible besides me.” And so I quote that passage from the Phaedrus, right? So I say, “Look, I just wrote this book about how conversation is, what thinking really is. So how is this book thinking, if it’s not conversation? That’s the problem.” I don’t know the answer is what I’m telling you. I really don’t. And I think it’s a big bad problem about my book. Maybe you think it just refutes the whole book. It’s possible.

See, I thought you might have said, it’s like save me. But it is a problem. I do want to say something about, so partly an attempt to come with a better … I’m working on this question by the way. I haven’t given up. OK. I’m working on it. And the way I’ve decided to work on it in the past month, is just by reading a lot on conversation in psychology, in linguistics, but mostly in sociology, on what happens in a conversation actually, how does a conversation work? And one thing I’ve learned from sociology, is that there’s a lot of stuff in written and spoken conversation that we use to create meaning that is missing … Sorry, in spoken conversation, but including on the phone, is what I meant. So in person, but also on the phone, on the phone is fine. But that we use to create meaning.

For instance, reaction times are really pretty important, that we can respond to each other really fast. OK. That’s important to create meaning, and that’s missing in written conversation, even if it’s texts. Even if it’s texting, text messaging and stuff, that’s still missing. And so I’m inclined to think there actually really is something special about either in-person conversation or at least conversation where there’s … It doesn’t have to be by sound because it could be sign language, but not written down.

And one of these sociologists that I read had such an interesting reading of the Phaedrus. Totally in passing. I mean, in a … Not a book on Plato at all. But what he said was that in some way the fundamental problem of speech is how to create agreement, how it is that we can think or say the same thing. And one way that poetry gets saying the same thing is by having a text that can just be repeated that way and the metrical structure makes it fixed so that we can say the same thing. And that’s a big innovation of poetry. Poetry propagates agreement, OK, by having a text. Even if it’s not written down, there’s a text. And that Plato’s … On this person … His name is Harvey Sachs. On his reading, what Plato is criticizing that aspect. He’s saying, “No. My kind of agreement, the kind that is better, the kind where when I agree with you, I can say what you said in different words. I don’t have to say your same words. I can say different words.” And that’s like a better kind of agreement.

And Plato is in a way putting himself forward as, “I’ve improved on the poetic method of agreement. The poetic method of agreement was same words every time. My method of agreement is you can say it a lot of different ways and still be agreeing.” And there’s something really valuable to that second kind of agreement, the kind where you can say it in a lot of different words and that there’s a sense in which we’re really agreeing when we can do that. And I guess I do … I thought that was such an interesting way to frame the Phaedrus passage as a critique on poetry where it’s not essential that the poetry be written down actually. It’s just that it be metrically fixed. And I guess I do find that very compelling. And so if I’m going to save my book, the way that I have to somehow save it, but I don’t quite know how to do it, is somehow it is part of a conversation and that’s partly your job or something like that. But now Judith is going to give a better answer.

Judith Butler: No. No. I don’t have a better answer at all. But it’s a totally interesting problem. In the acknowledgements, this is the part of the Phaedrus. I’m just going to read it. OK?

Agnes Callard: Yeah.

Judith Butler: Because we don’t do this generally, read some Plato out loud to a large group. OK. “You know, Phaedrus, writing shares a strange feature with painting. The offsprings of painting stand there as if they are alive, but if anyone asks them anything, they remain most solemnly silent.” So we actually have two analogies here. One is writing with painting. And both of them are then jointly analogized to a human form that’s standing there solemnly. So there’s an anthropomorphism in the middle of this discussion. “The same is true of written words. You’d think they were speaking as if they had some understanding, that is you’d think they were humans over there talking, but if you question anything that has been said because you want to learn more, it continues to signify just that very same thing forever.”

It’s like I beg to disagree because we interpret and reinterpret all the time, and I almost think all you have to do is invoke the classroom. We are reading texts together and interpreting and we’re finding meanings of them. And sometimes, for instance, this book I think is showing how Socrates can speak … Let’s use the anthropomorphism. Socrates can speak to our public situation in which people can’t speak to one another or they take opposition to be a reason to break relationships or to cease conversation. You’re suggesting there ways to have open disagreement or produce the space of disagreement or to be collaboratively involved in an inquiry where no one person has the answer alone.

So I think these are important values for our time and also perhaps in explaining what we do in universities and why it’s important. We don’t just circulate dogma and indoctrinate our students. But it seems to me if we stay within the anthropomorphic framework, we could say that text is speaking back all the time. We find different things in texts we’ve read a million times. And somebody else has an interpretation. Sometimes it’s through a comparison. Sometimes it’s through a translation. And suddenly it’s speaking differently, if we’re going to stay within the anthropomorphism. But …

Agnes Callard: Can I just ask you a question about that?

Judith Butler: Yeah.

Agnes Callard: That’s completely right, but Plato was totally aware of that because in the Protagoras we have this Simonides interpretation, right?

Judith Butler: Yeah.

Agnes Callard: We have the practice of interpretation happening in Plato. Why did he think that doesn’t count?

Judith Butler: I don’t know if he thought it didn’t count, but I think one of the things we’re missing here is that Plato is preserving, transmitting these conversations in writing. So we actually need the written form to have it transmitted and to have a text in the room that has been read again and again. And we have a whole scholarship, a whole set of readings. You’re refuting some of them. You’re drawing on others. And we’re in a classroom or a public setting where we’re trying to talk about all this. So there is an overlay of the written and the spoken.

I mean, if we imagine, OK, these were conversations that were recorded or re-crafted and then transmitted, the writing is what permits us to read the dialogue. The written form is what permits us because we can’t be present to it. We can pretend we’re present to it. We can extract it from the written version. And we also … Do we have a way of saying where Plato begins and Socrates ends? How would we verify? How would we … So it’s overlapped, the writing and the speaking. And even in this funny passage, it keeps expecting a human speaker from the written word. And there’s a kind of transposition of the two that’s happening even as there’s a distinction between them that’s happening all the time. So I just think maybe Socrates really did need Plato after all.

Audience 4: Hello. Is it on? Can you? OK awesome. Hello. So it feels like openness or maybe disclosure for it to work properly needs to have a kind of cooperative audience, an audience that is also engaged, Alcibiades has to believe that he won’t be hurt before the dialogue can continue. And that feels like one of the biggest barriers to maybe living a philosophical life today is that when you sit on the steps of the Art Institute, nobody really wants to talk to you. And so what do we do about that? And looking back, is there a better way to engage with the people at the Art Institute? Yeah.

Judith Butler: Maybe if there were text in the room.

Agnes Callard: I think that that’s right though, actually. So I think that texts really do help, that somehow there’s something just very intimate about a philosophical conversation. And it’s like getting into that with someone when you don’t know them at all, the text allows you to alienate it a little bit. So that’s one thought. I guess I think it’s not an accident that the places where we tend to pursue philosophy, and this is true for professional philosophers too, not just for students, the places where philosophy tends to happen is places that are designated for it so that we know this is a safe space for philosophy, like a room like this. We all know, “It’s OK here. We’ll be fine.”

And it’s actually harder to move it into other spaces. And that’s the thing I’m working on. And I’m much worse at it than I would like to be at this point in my life. And I think that part of why I’m so bad at it is that all the forces that make the other person feel nervous or worried, I feel them. And I instinctively just … I’m like, “Look, I can make them feel comfortable so easy by just asking just, ‘Oh, when did you get in? And when are you leaving?’” There’s a set of questions I know I can ask where this will be fine, and I’m going to force myself to move into that uncomfortable space, and I have to fight something in myself to do that.

And so it’s a thing I genuinely feel bad about a lot of the time, is that I’m not doing as much of this as I ought to because I am myself letting myself be pulled into the normal social conversation that I end up hating and feeling just stressed out by and stuff. So I feel like your problem is a problem that I’m thinking about a lot, but I’ve only come up with solutions for it in these safe spaces. I’m still looking for a more general solution.

Judith Butler: But doesn’t Alcibiades say, “I don’t feel safe in this conversation.”? right? I mean, isn’t that what he’s saying? It’s like, “You’re harming me.” And so then you have to … Then Socrates has to work with him. It’s like, “This is not harm. You are not being harmed by having your beliefs challenged.”

Agnes Callard: Right, but Socrates has that faith of, “I’m going to be able to do that.” You have to believe that you’re going to be able to do it. And I can believe in that sometimes. And then sometimes I’m like, “No. This person’s just going to be stressed out by me,” which really does happen to be fair to people. So it’s like …

Judith Butler: Well, because we don’t have a norm. Right?

Agnes Callard: Right. Right.

Judith Butler: Because we’re not used to it.

Agnes Callard: Exactly.

Judith Butler: It’s like we would like to say, “Hey. Stay with me. I’m going to repudiate you and I want to hear what you have to say.”

Agnes Callard: Yeah. Yeah. Exactly.

Judith Butler: “And I’ll withdraw my repudiation if you turn out to be right. But stay in this.” And they’re like, “I’m not doing this.”

Agnes Callard: Exactly. Exactly.

Judith Butler: You know?

Agnes Callard: Yes.

Judith Butler: Nobody … We just don’t have a practice. And I think that’s part of what you’re trying to do by going public in the ways that you are, is suggest this as a public practice so that the world is less stressful for people who want to talk in this way.

Agnes Callard: Yeah.

Moderator: I think there’s a question in the back of the room.

Audience 5: Yeah. Thanks so much for this. I just wanted to follow up on the previous question. And it seems often … So Alcibiades says he’s willing to engage with Socrates because he feels he will not be harmed, but I think there are some lines of inquiry that people often feel maybe are harmful to ask questions even in good faith, maybe even in the context of a philosophical forum or a classroom. So if we’re approaching inquiry in this Socratic spirit, do you think that there are lines of inquiry that maybe we shouldn’t be pursuing or, yeah, that should be closed to us? Thanks.

Agnes Callard: So it depends on where the quantifiers are. I actually think in pretty much any conversation, no matter how philosophical, there’s many, many questions you can’t ask and lines of inquiry you can’t pursue in that conversation. So that’s the norm. The norm is that there’s just a lot of territory that’s carved off. The great thing is if there’s anything you can ask about that is let’s focus on the positive. If we can get an inquiry going at all, that’s awesome. Do I think that there are just particular questions where you can’t ask them anywhere of anyone ever or something like that? I mean, that case would have to be made to me, but I do tend to think that there are … When …

So a thing I discussed in the book is politicization and I give a kind of account of what politicization is. And it’s basically when a question is politicized, that’s kind of a worst-case scenario for pursuing an inquiry. It’s going to be hard to pursue an inquiry into the question if it’s politicized in the group that you’re trying to inquire into it. It might still be really important to do it, but it’s going to be harder and it’s not going to help much if you just pretend that the politicization’s not there.

And so what I try to do is explain why certain questions in certain contexts are hard to inquire into. But I do think that in principle, the way to get around the politicization would be to stop seeing the inquiry into the question as a symbolic zero-sum contest between two parties. And the question is then just can you do that or not? Can you pull that off or not? And it’s a hard thing to pull off. And people who … You see Socrates kind of pull it off in the Gorgias under pretty adverse circumstances. So yeah, that’s what it takes.

Moderator: Maybe one final.

Agnes Callard: Can I get Spencer’s question?

Moderator: Oh. Where’s Spencer?

Agnes Callard: He’s right … Raise your hand, Spencer.

Moderator: Oh. OK. Thank you.

Spencer: Thanks. That was a great talk. I guess what I wanted to ask about was what does what we’re saying about sort of Socrates’ method, how does that interact with what we should think about his actual views? Because I feel like somehow one of the sources of skepticism maybe people have about Socrates is he has this method, but then he gets to these views that people uniformly find difficult to believe, implausible. So I mean, maybe part of the answer is that you believe some of these views, but is there a systematic reason why other people don’t? Or is it just on a case-by-case basis they don’t believe this one, they don’t believe that one?

Agnes Callard: Yeah. So I do believe these views, and I argue from them in the book. So I try to explain … So I think two of the ones that I think are really central is there’s no such thing as weakness of will and never, ever, ever, ever get revenge. And what I think the way that Socrates argues for those two views, this is one, I think of this as one of the coolest interpretive moves of the book, maybe nobody else cares, but from my point of view, they’re parallel arguments. They’re not in same texts. One of them’s in the Crito and one of them’s in the Protagoras, but basically what he shows you is just doing some very simple word substitutions and not using words ambiguously and these conclusions are going to fall out of simple reasoning. And the thought there is if you’re just committed to regulating your life by means of thought in this way, you’re actually going to have to come to these conclusions. But the proof there is in those arguments and whether you think they work or not.