A spate of suicides drew this alumna back to UC Berkeley to confront mental health issues in academia

Encouraged by Wendy Ingram, a 2014 Berkeley Ph.D. recipient, eminent faculty members shared their experiences with depression and anxiety to help bring these struggles into the open.

Josh Egel

April 21, 2025

The academic year 2013-14 changed the direction of Wendy Ingram’s life. Over the course of a few months, four members of the UC Berkeley department in which she was a graduate student died by suicide: an undergraduate student, a doctoral student, a post-doctoral fellow and a faculty member.

The tragic events left many in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology (MCB) reeling, but Ingram also found that the suicides prompted co-workers to share their own mental health issues. She discovered that, like herself, about half the people she talked to had sought therapy at some point in their lives.

“Everyone was struggling, but none of us was talking to each other about it,” Ingram said. “There was a humongous cultural and professional stigma against struggling with your mind. If you are reliant on your mind for the work you’re doing, there’s this inherent pressure to ‘have nothing wrong with your brain,’ because that’s the most important tool that we work with when we’re in the academic space, when we’re in research.”

She graduated with a Ph.D. in 2014, but returned to campus in 2018 — during her training as a postdoctoral fellow in psychiatric epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University — to develop and test interventions that she said encourage people to be “more open about sharing that they’re struggling and increase their chances and ability to get the help that they need.”

Ingram subsequently founded a nonprofit, Dragonfly Mental Health, to bring these programs to universities around the country and the world.

In 2018, Matthew Welch, who at the time was the head graduate student adviser in MCB, encouraged Ingram to speak at a departmental retreat about mental health awareness. Her talk resonated with many of the more than 100 students and faculty and staff members there, so he invited Ingram back for subsequent retreats. She is now helping the department develop a sustainable program to encourage discussion of mental health issues that includes, when necessary, referral to counseling services at University Health Services (UHS).

The following year, Ingram convinced Berkeley faculty members to describe their own mental health struggles in a video that debuted at a series of retreats.

“People were crying after watching this film,” Welch said. “It was really quite powerful, and you realize, ‘Oh, my god! This is actually making a difference.’”

One interviewee was Richard Harland, professor of molecular and cell biology, who today is dean of biological sciences in the College of Letters and Science. He has struggled with depression much of his life and credits reaching out to friends and psychiatrists for support, and seeking medication, for his ability to deal with it.

“I think that when you can get people you respect to tell their own stories of depression, it helps to break the stigma,” Harland said. “One of the great changes — and I think a lot of this has been due to Wendy and her colleagues — is that people are much more educated about the signs of depression. They’re being more active and talking to people who they suspect may be depressed. I think participating in that video may turn out to be one of the most useful things I’ve done.”

Wendy Ingram

Randy Schekman, a Nobel laureate and professor of molecular and cell biology, recounted in the video how he was beset by panic attacks as a young professor at Berkeley, despite having distinguished himself early in his research lab. He said his anxiety before delivering seminars led him to try various medications to calm his nerves.

“I think this is not uncommon. It just doesn’t get discussed because most people wouldn’t care to be open about that,” he said.

Schekman said he eventually learned to handle anxiety without drugs or therapy, and that his attacks sensitized him to the stresses and anxieties of the students and postdocs in his lab.

“I eventually just learned to cope with it,” he said. “But having experienced that, knowing that it happens even to someone who is outwardly very confident, like me, I know it’s a real thing. Sometimes there aren’t simple solutions. In my case, it was a combination of Valium and then propranolol that put it under control. I still occasionally have panic attacks, but I know how to bring it back to basal level.”

The success and impact of these films cemented Ingram’s decision to found Dragonfly in 2020.

A vision: excellent mental health among academics worldwide

Ingram, who joined the MCB department in 2009, is keenly attuned to mental health issues because bipolar disorder runs in her family. As soon as she got medical insurance through the campus, she sought out mental health counselors and was diagnosed with the disorder, which later claimed the life of a cousin by suicide.

Adrienne Greene

“I went in to seek, proactively and preventatively, psychiatric connection and care because I knew graduate school was going to be the hardest six years of my life. I knew it was going to be high pressure. I knew I was going to be pushing myself to the limits of my cognitive and physical abilities in whatever way that means,” she said. “I was preparing for that as best I could.”

In the face of her colleagues’ suicides, she helped found a student-run organization, the MCB Grad Network, which focuses on mental health.

“Even then, the stigma was so high that we didn’t include wellness, mental health or anything overt in the title pointing to why we were starting this grad network,” she said.

Her experiences in graduate school spurred her to pivot from the field of cell biology — her thesis was on the lasting impact on mice of toxoplasmosisinfection — to psychiatric epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. There, she sought to better understand and research the molecular underpinnings of mental illness and the pharmacological and behavioral approaches that can improve them.

Then, another tragedy struck. A friend, Cris Alvaro, who had received a Berkeley Ph.D. in 2015, died by suicide in 2018 while a postdoc at UCSF. An activist for transgender rights, they strongly supported underrepresented individuals in the sciences and were involved in activism for the STEM LGBTQ community, first-generation graduate students and communities of color. Alvaro referred to themself as a “mental health warrior.”

In talking with Alvaro’s friends and colleagues at Berkeley, Ingram said she knew that “there’s stuff we can do about it, like education and skills training and fighting stigma and organizational support and peer networks.”

Matt Welch agreed. “At that time, it became even more clear that this was something that was necessary for us to respond to in a comprehensive way,” he said.

Ingram’s first presentation at a departmental retreat took 20 minutes, but it was followed by more than an hour of discussion. Students and faculty members alike unloaded about their struggles and a desire for more openness.

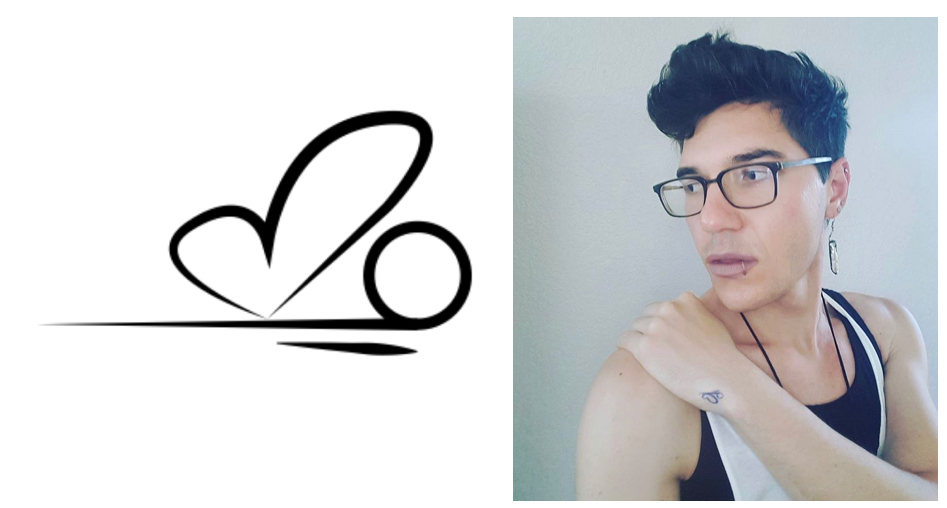

The organization she founded in 2020 honors a dragonfly tattoo that Alvaro designed and sported on their wrist, and which Ingram adopted as the Dragonfly’s logo.

Dragonfly Mental Health

The Dragonfly program that Ingram developed includes videos with first-person interviews, structured discussions about mental health issues such as depression, imposter phenomenon and power abuse, and steps toward making these interventions ongoing within a department. To date, Ingram has interviewed more than 40 academics around the country for these videos, working with the American Society for Cell Biology, the Orthopedic Research Society and Johns Hopkins University, among others, and presented more than 380 workshops to more than 60,000 students and staff and faculty members in 38 countries.

“Now, (Dragonfly is) at the forefront of equipping people with skills and knowledge to have more effective and humanizing conversations about these things so that people don’t suffer in silence, and they don’t have to have those questions of uncertainty in their minds,” said Andrew Devendorf, now a clinical psychologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Seattle Puget Sound Veteran Affairs Hospital. He and a former classmate of Ingram’s, Sarah Wilson, now at Dragonfly, collaborated with Ingram on a study of the effectiveness of first-person narrative interventions that was published last year in the journal Psychological Services.

Providing awareness and support

Berkeley has long had an awareness campaign about student mental health, typified by the Gold Folder, created a decade ago to help faculty and staff members recognize signs of distress in students and direct them to services at UHS and locally. That folder and a Mental Health Handbook have been key to alerting students to available crisis resources.

Jennifer Books

But graduate students sometimes feel “in between undergraduate students and staff,” said Tobirus Newby, assistant director of outreach and engagement at UHS. To address that, specialized graduate student advisers reach out regularly to departments, and mental health counselors are embedded directly in some campus units, such as Berkeley Law and the Haas School of Business.

Within departments, programs like Dragonfly “can be complementary and get community buy-in” to raise awareness of these services, Newby said.

Despite better awareness of students’ mental health, faculty and staff members don’t always recognize or accept symptoms among themselves. Stephen Hinshaw, a Berkeley Distinguished Professor of Psychology who studies ADHD, related mental conditions and the stigma surrounding them, helped create the Gold Folder in 2013.

“There’s still a stigma that if you’re a faculty member with a pretty serious mental illness, that flaws you and doesn’t enable you to think rationally, and you’re going to be at risk in the classroom and at risk in committee meetings,” Hinshaw said. “And so people keep it under wraps.”

Hinshaw, Ingram and Welch suspect that academic research attracts a greater percentage of people with emotional and psychological issues, based on proven associations between neurodiverse characteristics and creativity.

“Who are the most productive people in just about any society ever studied? The first-degree relatives — the parents or the kids or the siblings — of people with bipolar disorder, because they’ve got some of the genetic liability, which may actually yield spark and ‘juice,’ without going into full mania or the suicidal depression,” Hinshaw said. “If we systematically insist on excluding these people because of the stigma, we’re going to cut out the most brilliant and creative people wanting to do research on and help other people.”

Yet, even for those without a family history of mental illness, academic work can be intense.

Takeaways from Dragonfly Mental Health

- Mental health, like physical health, is influenced by both biological and environmental factors.

- Mental health has been found to require community support for sustained engagement in care and best outcomes.

- Professional, societal and self-stigma are the primary barriers academics face in seeking care for themselves or actively supporting colleagues or trainees.

- Increasing knowledge and supportive skills, decreasing stigma, formal and informal peer support, and sustained administrative investment in mental health are the most effective ways to create a mentally healthy academic community.

“It’s not only a living and wages, but it’s your identity, your ‘calling,’ your esteem and your status in the field,” Hinshaw said. “Whether in the humanities — drawing, writing, painting, dancing — or whether producing articles and books in the sciences, it’s more than a job.”

Third-year graduate student Anastasiya Trzcinski is currently experiencing that pressure and intensity. After learning about Dragonfly in 2023, she joined the department’s Wellness Committee to help improve mental health awareness among graduate students. She’s helped set up workshops on burnout and organized de-stressing gatherings.

“In my own personal relationships in the department, many of us are struggling with severe or not so severe mental health conditions, … because being in this space can be really difficult,” said Trzcinski, who works in the lab of Kathleen Collins, an MCB professor in one of Ingram’s videos. “I think it’s important that the department demonstrates a commitment to recognizing people’s struggles with mental health and does tangible things so that everybody can feel safe and included.”

Suicide postvention

While Dragonfly focuses on mental health, in general, Ingram hasn’t forgotten the special trauma suffered when a friend or colleague dies by suicide.

Irvin Ingram

In 2022, the program began collaborating with Workplace Suicide Prevention to adapt its Manager’s Guide to Suicide Postvention plan to an academic setting, working initially with the MCB department. Ingram anticipates that the revised program will be ready for local and global use in 2025 and hopes to start training trainers this summer.

“When somebody dies of something like cancer, our society has more straightforward scripts for how to support other people who endure those tragedies,” Devendorf said. “Whereas with suicide, because it’s not talked about, that results in this vicious cycle of people questioning in their minds, ‘Should I bring this up with somebody? Should I ask what happened? Should I send flowers?’ What I really commend Dragonfly for doing is that they’re taking this series of tragedies and identifying that people didn’t know how to respond, even in positions of power.”

Ingram’s approach was tested two years ago after another suicide at Berkeley, which prompted Ingram to connect those who were grieving with psychological support.

“This is leading edge stuff,” she said. “A lot of other departments are wanting to do things like this, but don’t even know where to start.”

Devendorf, who also has a history of depression and lost a brother to suicide, joined Ingram to assess the value of the video, followed by moderated discussions, for graduate students, postdocs and faculty members. In their 2024 paper, he and Ingram reported that students, in particular, appreciate the open and honest discussions, but wish for even more openness.

It was very impactful when faculty members shared their stories, said Devendorf, because it showed students “that you can still succeed even when you have something like depression, anxiety or substance use disorder.”

Ingram noticed a reluctance to be interviewed on video among groups historically marginalized in the sciences — women and people of color — and among graduate students. “They still felt like it was a risk; that there was enough public and professional stigma that they may face negative consequences … sharing their stories more broadly,” Ingram said.

“A graduate student with depression might be viewed as less likely to be able to function in graduate school,” Devendorf said, leading faculty members to avoid mentoring them or putting them on projects “because you think that they’re going to be lazy or unmotivated or unable to complete the tasks.”

Hinshaw hopes to collaborate with Ingram to establish a similar program in the Department of Psychology. Clinical psychology is one of the most selective programs across academia to get into, he said, and just a decade ago, disclosing a mental illness could keep you out.

But times have changed, said Hinshaw, who published a memoir in 2017 about his family’s struggles with mental illness, and his own. “If the hard-core gene scientists can talk about this,” he said, “let’s get some psychology faculty and students talking about this as well.”

Ingram, too, hopes to use the pilot program in MCB to spread the word throughout higher education nationwide, creating systemic change. She also acknowledges that there is much more work to do to fight the stigma of mental illness, especially among women and underrepresented minorities. Added Trzcinski, “If we’re not all at our best internally, then the science that we put out isn’t going to be the best science that it can be. That fact can be forgotten sometimes in academia.”

Dragonfly Mental Health