To understand immigration today, a UC Berkeley sociologist documented 200 personal stories

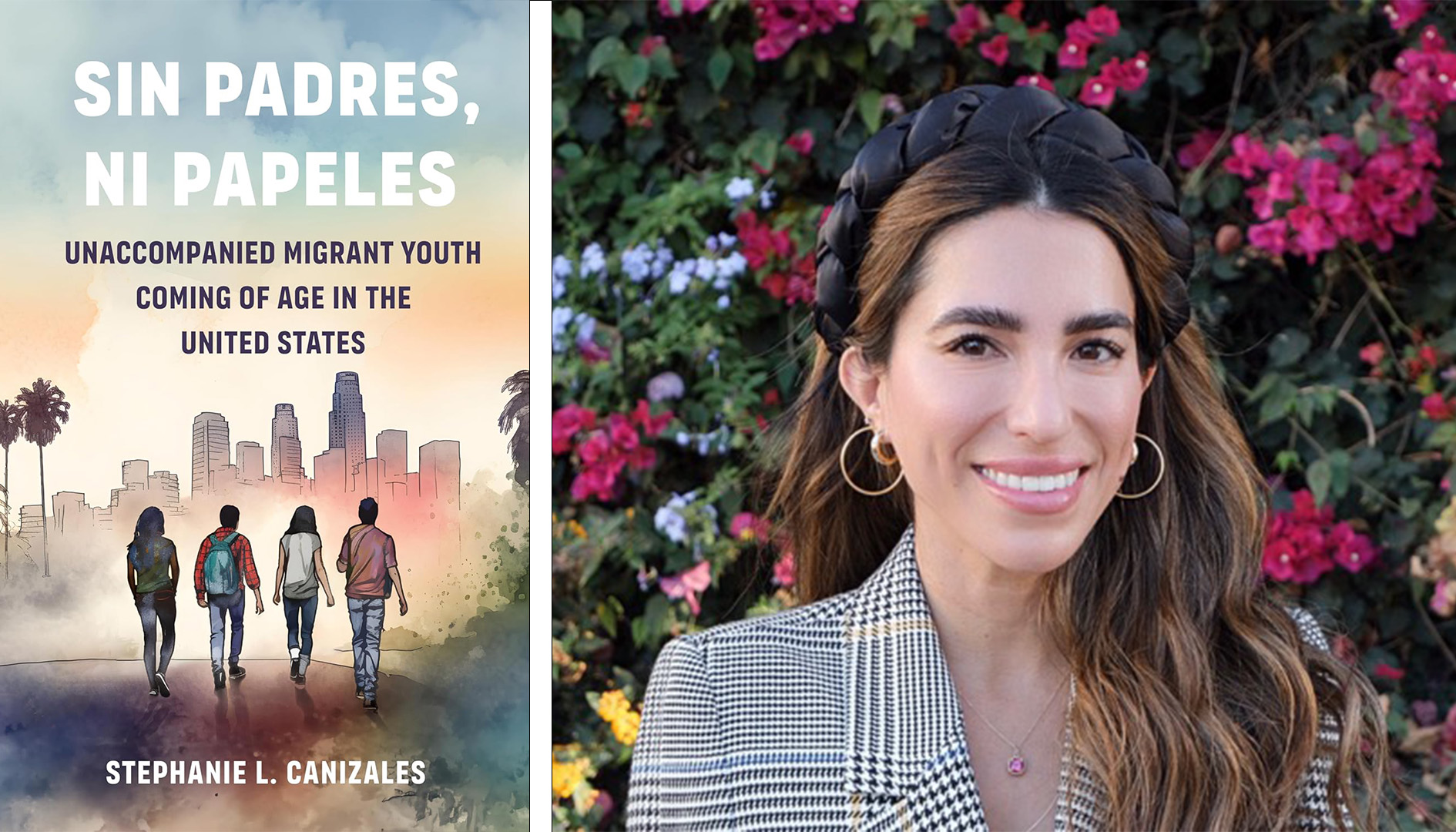

Stephanie L. Canizales spent years interviewing undocumented young people. She says their accounts matter — especially in today's chaotic world.

Jon Putman/Sipa USA via AP

April 24, 2025

Early in Stephanie L. Canizales’ recent book about unaccompanied migrant children in L.A., she introduces a boy named Tomás. When he was 2, Tomás lived in poverty in Guatemala and helped his sister shine shoes. Abandoned at 10, he dreamed of having clothes, food and shelter. He joined his sister in the U.S. at 14, but soon left when she feared his undocumented status might draw attention from authorities and risk her U.S.-born child’s future.

He wound up sleeping on the floor of a garment factory. “Why,” he wondered, “am I not a kid who was born here?”

Tomás’s story is one among many that Canizales, a UC Berkeley assistant professor of sociology, uses in Sin Padres, Ni Papeles: Unaccompanied Migrant Youth Coming of Age in the United States to explore how cultural practices and legal policies shape the lives of undocumented young people in California. Some youth find reprieve and stability, she said. But many are exploited for their labor, lack family support and grow into adults in a country that leaves them in the shadows and vilifies them for political gain.

The book — her first — is anchored in sociological theory. But the way Canizales sees it, her job is also to make readers care despite the many other issues in need of attention today.

“I’m really trying to challenge this idealized-on-a-pedestal idea of who immigrants should be for us to consider them human, worthy of inclusion and deserving of protection,” Canizales said.

Canizales, who also is faculty director of the Berkeley Interdisciplinary Migration Initiative, has emerged as a leading scholar of undocumented young people in the U.S.

Her second book, Everyday Futures: Language as Survival for Indigenous Youth in Diaspora, is due later this year. Both books, and a third project about how seeking asylum can be traumatic for children and their caregivers, draw from almost 200 interviews and a decade of ethnographic research in L.A.

Her up-close assessment of immigrants reveals how political double standards have cast them as a drag on the system rather than a key to a thriving society. And at a time when many proclaim to care about the lives of young children, U.S. policy punishes adults in the U.S. who were brought here as children.

“If not leverageable for the sake of agenda-setting or even tone-setting to the public, the population is completely forgotten,” Canizales said. “And that really haunts me.”

Six years of interviews

Canizales first knew she wanted to be a teacher in the second grade. She initially wanted to work with grade-schoolers, and by high school, she was interested in educating teens. But one day in 2012, as a graduate student at the University of Southern California, she decided to teach adults and mobilize them to help others.

That day, she was the volunteer coordinator at an event at the Los Angeles Convention Center, helping undocumented young people enroll in the newly created Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Signed into law by President Barack Obama, DACA provided protections to undocumented immigrants who had arrived in the U.S. as children.

Directing the hundreds of volunteers was rewarding work. It was also emotionally and physically exhausting. Surely, she later thought, there must be another avenue to mobilize people that wasn’t quite so one-off and taxing.

I’m really trying to challenge this idealized-on-a-pedestal idea of who immigrants should be for us to consider them human, worthy of inclusion and deserving of protection.

Stephanie L. Canizales

Her answer arrived while at USC, where Canizales was pursuing a master’s degree and, ultimately, a Ph.D. in sociology. She became focused on a career teaching hundreds of college students packed in lecture halls how to understand society, think about inequality and seek to change the system.

“This was a way to inform people of the moment,” Canizales said. “I could educate people about pressing social issues and hope that, through that education, they would be motivated to activate their curiosity and desire for social change.”

While working toward her Ph.D., Canizales spent six years conducting in-depth interviews with 75 young people across L.A. She zeroed in on the lives and circumstances of undocumented teens, many of whom worked under-the-table jobs sewing shirts or washing dishes for less than minimum wage. Some attended school at night; most didn’t. As she conducted interviews, President Donald Trump was fanning an anti-immigrant wave and endorsing policies that separated children from their parents and broke up families across the country.

Canizales said roughly 140,000 unaccompanied children from Central America, Mexico and other countries are apprehended every year at the U.S.-Mexico border — double the number from 2014, when the U.S. declared the number of crossings a humanitarian crisis.

Her Ph.D. work found that unaccompanied children who arrived in the U.S. hoping to be welcomed by relatives who had settled here were instead viewed as a danger to these family members’ legal and socioeconomic status. So the newly arrived children became adrift again and were forced into low-wage work to pay for essentials like food and shelter. Social programs and policy chronically ignored their circumstances.

Moreover, Canizales observed a Catch-22 for immigrants: Even those who did everything by the book to become part of broader society — to incorporate — were severely limited.

While milestones of American success often include financial stability, having a family and owning a home, immigrants who achieved them in young adulthood are still considered outcasts. Canizales said that creates a situation that’s impossible to win.

“We have assumptions about what immigrant incorporation, a ‘successful’ immigrant, a ‘good’ immigrant look like. And likewise, we have assumptions about what a ‘good’ child looks like,” Canizales said. “Why do we hold certain groups of people to account when those of us who have, by every other marker, the ability to reach those things have not done so?”

‘The quicksand that was under me’

After graduating from USC and working briefly at Texas A&M, Canizales arrived at UC Merced as an assistant professor of sociology. She started writing Sin Padres, Ni Papeles in 2021, knowing she wanted to chronicle her time with some of the young people she met and offer clear policy recommendations rooted in sociological research for the greater good.

But as the writing process unfolded and her participants’ stories unfurled on the page, she also reflected on how reliving those interviews had made her feel.

I wanted to really capture the uncertainty, the quicksand that was under me.

Stephanie L. Canizales

In an appendix that closes the book, she recounted the “migraines, constant colds and persistent tension around my neck and shoulders.” She described feeling anxious and worried for children she met and the paradox of being a researcher climbing the academic ranks and gaining status in society “while telling the stories of youth and young adults who had (and continue to have) few options to do the same.”

Not all aspiring academics include details about their fears, illnesses and own need for therapy in the closing pages of their debut book. But Canizales felt it was important for future researchers to understand that empathy can be a tool, not a liability.

“I wanted to really capture the uncertainty, the quicksand that was under me when I did the work, even as people see me in 2025 as knowing,” Canizales said. “I can tell you now how I did it. But when I was doing it, I wasn’t really sure what I was doing.”

She’s more confident now. Children are the experts on their lives, she said, and it’s essential for us to listen. And seeking a way to make people understand and care just a little bit more about them is central to her writing and lectures.

If she can make you remember people like Tomás, she’s succeeded.