Stunning Diego Rivera mural starts a new chapter at UC Berkeley’s Doe Library

The fresco, from the collection of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, is "like a window into another world.”

May 1, 2025

The mural, painted by the famed Mexican artist Diego Rivera, is a portal into another time and place.

Measuring over 5 feet tall and nearly 9 feet wide, the fresco, completed in 1931, depicts workers tending an orchard in California, bathed in the glow of white-blossoming almond trees. A basket holding the fruits of their labor, surrounded by children with outstretched arms, appears in the foreground.

“What I love about this piece is it actually feels like it’s drawing you in,” said Beth Dupuis, UC Berkeley’s senior associate university librarian, who led the library’s efforts to display the painting, on loan from the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). “It almost feels like a window into another world.”

For decades after it was gifted to the campus, the artwork, “Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees,” was on display in Stern Hall, the campus’s first dormitory for women. Now, it’s starting a new chapter at Doe Library, at the heart of the Berkeley campus. At the library, anyone — from art aficionados to stacks-bound students to members of the public — can take in a slice of history and witness firsthand the rare beauty of a work by one of the world’s most celebrated artists.

The mural’s prominent placement at Doe, which nets hundreds of thousands of visits a year, is the result of a conversation started by Julie Rodrigues Widholm, BAMPFA’s executive director. With the piece on display in the library, a large audience can appreciate the artwork, and experts at the nearby museum can more easily monitor its condition.

“This is a huge opportunity — not just for Berkeley, but for anybody who’s interested in art,” said John Alexander, BAMPFA’s director of collections and exhibitions, who led the museum’s efforts to publicly display the mural.

Jami Smith/UC Berkeley Library

Behind the brushstrokes

In the fall of 1930, Rivera and fellow artist Frida Kahlo journeyed to San Francisco after a lengthy campaign by Bay Area residents to draw the muralist and his talents northward.

During their monthslong stay, the couple, who had married the year before their arrival, lived in Jackson Square, forged connections with such luminaries as photographer Dorothea Lange, and immersed themselves in their art.

In Mexico, Rivera had been known for his frescoes, suffused with revolutionary politics. But he had yet to paint a mural in the United States.

While in the Bay Area, he undertook several commissions, including his first painting in the U.S.: “The Allegory of California,” an enrapturing mural gracing a stairwell at the Pacific Stock Exchange Luncheon Club, now the City Club of San Francisco. Tennis star Helen Wills Moody, a Berkeley alumna and Olympic gold medalist, served as the model for the main figure in the painting — a mythical warrior queen, Calafia, who hails from a 16th-century Spanish novel and has often been portrayed as the “Spirit of California.”

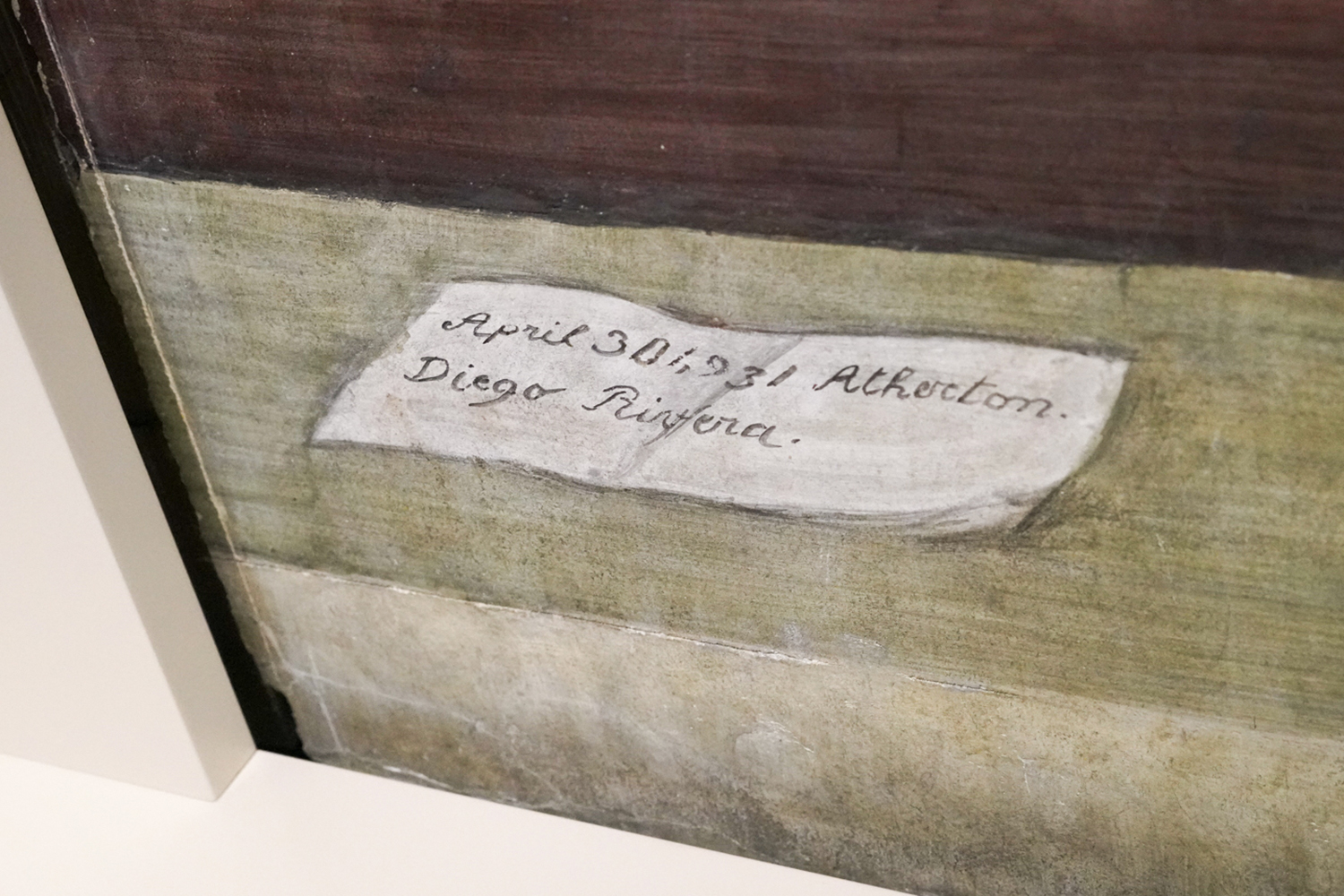

In Atherton, Rivera painted “Still Life and Blossoming Almond Trees,” now on display in Doe. The mural was a private commission by Rosalie Meyer Stern, a civic leader and philanthropist, and the wife of Sigmund Stern, the president of Levi Strauss & Co.

With his signature bold style and warm, earthy tones, Rivera captured an idyllic scene of laborers working in the Sterns’ orchard, on the San Francisco Peninsula. The artwork has echoes of Rivera’s home country, of which California was once a part — its people and the bounty of the land.

“He felt a very deep connection with the physical landscape of Mexico and California,” Alexander said. “He really kind of saw them as a continuum of culture and physicality.”

The youngsters in the foreground of the painting, grasping for fruit, are the Sterns’ grandchildren, joined by a surprise visitor.

“The figures in the mural originally were me, my sister, and strangely enough, my sister’s imaginary friend, whose name I don’t remember right now,” recalled Peter Haas, one of the Sterns’ grandchildren, in an oral memoir based on interviews at The Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center.

Rivera had apparently initially neglected to include Walter Haas, Peter’s brother, but corrected the omission by painting him into the background as one of the laborers, according to the memoir.

Peter Haas remembered Kahlo’s presence on the property while Rivera worked. “Her charm kind of eased the pain of sitting there for a few hours for my portrait,” said Haas, who went on to become the president and CEO of Levi Strauss & Co. “Her appearances on the scene made life a little more interesting for this young boy.”

Jami Smith/UC Berkeley Library

‘On the level of Picasso’

In 1956, upon Rosalie Meyer Stern’s passing, the mural was bequeathed to the University of California, where it was displayed in Stern Hall at Berkeley. The dorm was a fitting location: Its namesake, in addition to commissioning the artwork, provided funding for the construction of the residence hall.

The artwork had its most public outing when it was featured in an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). The show, “Diego Rivera’s America,” opened in 2022 and brought together more than 150 works to highlight the artist’s output from the 1920s to the mid-1940s, a time when Rivera’s travels in Mexico and the U.S. were shaping his conception of North America.

“I was very excited to learn that UC Berkeley had this important artist’s work when SFMOMA requested to borrow it for its major Rivera retrospective,” Rodrigues Widholm said. “I began to wonder if it could be placed in a more public place on campus upon its return.”

After the exhibit closed, the mural came under the care of BAMPFA and officially joined the museum’s renowned collection of more than 25,000 artworks. The long-term display of the mural in Doe supports the library’s goal of enriching the lives of students, as well as Rodrigues Widholm’s vision to make BAMPFA’s collection more publicly accessible and to foreground the work of Mexican artists.

“I’m so grateful to our library colleagues who supported the idea of having the artwork installed in Doe Library,” Rodrigues Widholm said.

At Doe, the mural is on display in a protective case at a well-traveled crossroads on the first floor, near the entrance to the Main (Gardner) Stacks and across from the doorway to the AIDS Memorial Courtyard. Although anyone can behold the artwork’s beauty at Doe, a Cal ID is required to enter the library after 7 p.m.

It’s “wonderful and fortuitous” to have Rivera’s work on display in the library, said Todd P. Olson, a professor in the Department of History of Art. Olson hopes to look at the mural with the students in his undergraduate seminar on still life, which meets in Doe, he said.

“It is important to see the painting as an artifact — a human-made thing, a craft object — that is related to the artist’s body as it is related to our own,” Olson said.

The library provides “pretty unprecedented” access, Alexander said, and broad exposure to the work of an artistic luminary.

“He’s on the level of Picasso, really, as far as importance,” he said. “I just hope that (the mural) would either ignite or continue to sustain interest in his work and the museum.”

The painting is beautiful and inviting, Dupuis said, but it also has the potential to spark curiosity and inspire inquiry into a range of topics, from art to agriculture to the story of the mural itself, its subjects and its historical context.

“We’re a library, so we’re always about education and learning,” she said. “I think it could be a good exercise for people of any age to look at the mural and think more deeply about the world around them.”