This university alliance is training students to strengthen tribal food, energy and water systems

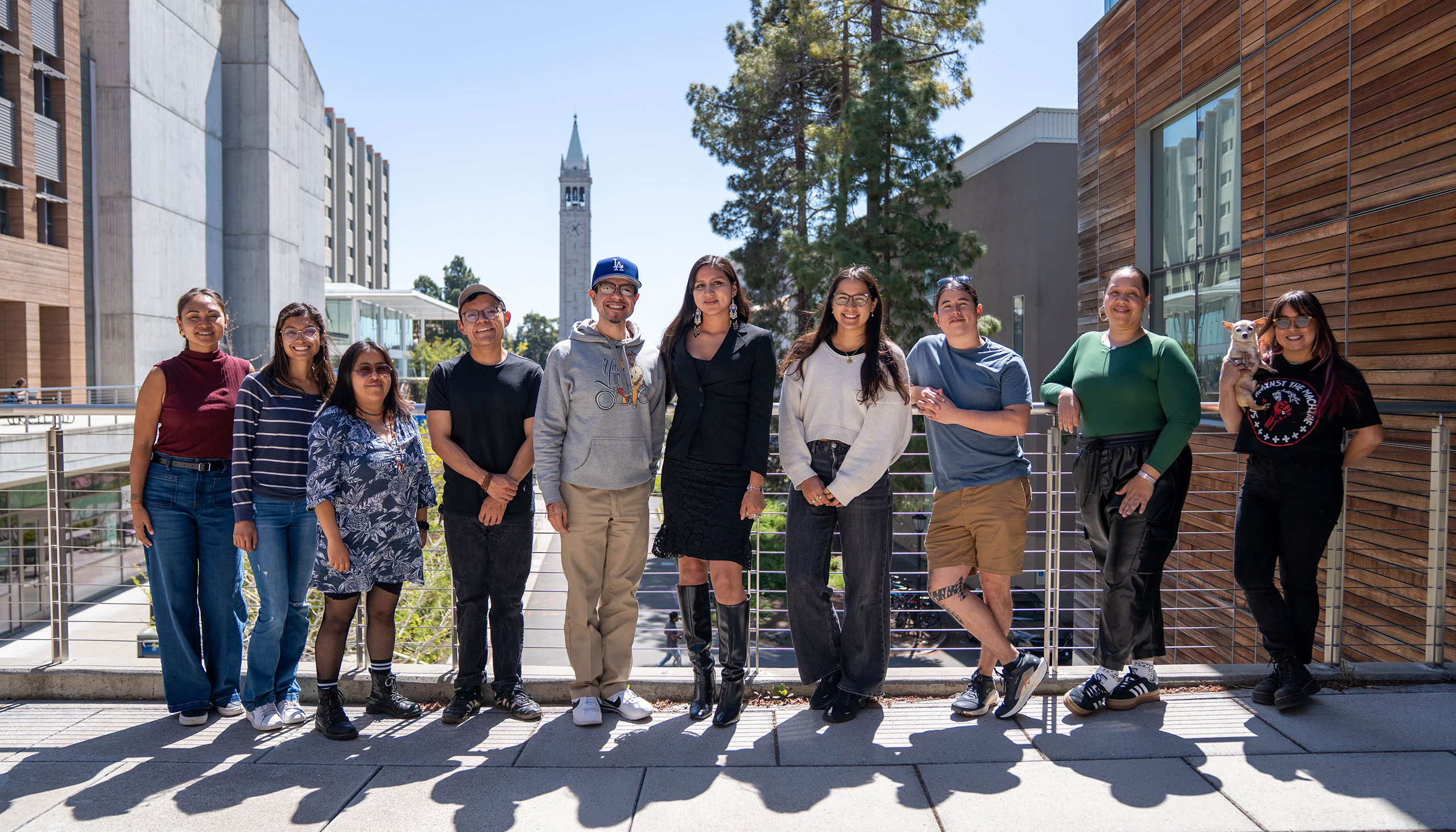

The Native FEWS Alliance, a multi-university consortium led by UC Berkeley and the University of Arizona, is one of hundreds of programs affected by National Science Foundation funding cuts.

Diego Moran/UC Berkeley

May 22, 2025

For eight generations, Kanani D’Angelo’s family has lived in ‘Aiea, Hawai’i, at the outskirts of Honolulu near Pearl Harbor. The area is now paved with roads and residential subdivisions, and the ‘Aiea stream, which gives the area its name, is restricted to concrete channels and underground culverts. But stories told by D’Angelo’s family recount a time before colonization, when the land was home to lush lo’i kalo (taro fields) and loko i’a (fish ponds) that provided ample food for the community. These were part of an integrated land and water management system called an Ahupua’a, which encompassed the entire watershed of the ‘Aiea stream, from its headwaters in the mountains to its outlet in Pu’uloa, now known as Pearl Harbor.

As a graduate student in UC Berkeley’s College of Environmental Design, D’Angelo is working with her home community to identify strategies for incorporating traditional Ahupua’a practices into urban environments. These strategies include restoring the 400 year old ancient royal fishpond, Loko Iʻa Pāʻaiau and marking the locations of streams that have now been diverted underground.

“Pu’uloa used to be home to over 20 fish ponds,” D’Angelo said. “The water is still there, the practices are all still there, they’ve just been buried.”

Courtesy of Kanani D’Angelo

Bringing back resilient Ahupua’a practices could help D’Angelo’s community maintain its cultural identity while providing food and revitalizing the local ecosystem. But tackling this holistic, community-oriented work in a Western academic setting — which often prioritizes deadlines, publications and subject-matter silos — is hardly easy. D’Angelo says that mentorship, community and support provided by the Native FEWS Alliance have been key to her success at Berkeley.

Launched in 2021 with a five-year, $10 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Native FEWS Alliance is a multi-university consortium designed to equip students with the multi-disciplinary skills they need to strengthen food, energy and water systems (FEWS) in tribal communities. Though the alliance has benefited numerous students like D’Angelo, the future of the program is now in jeopardy after its funding became one of approximately 380 NSF grants unexpectedly terminated earlier this month.

“This award is focused on innovative research and community partnerships linking two interconnected challenges: a crisis in access to food, energy and water in Native American communities; and the limited number of qualified science and engineering specialists who have the educational background and professional experience to address these needs,” said Alice Agogino, Distinguished Professor of the Graduate School at UC Berkeley. “Open to all populations, the focus of the alliance is on students who possess or seek the necessary skills to address these challenges.”

Agogino is co-principal investigator of the grant, along with Karletta Chief, a University of Arizona professor and extension specialist. The alliance also includes partners from more than 20 public, private and tribal colleges and universities, as well as from nonprofits, such as the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

Diego Moran/UC Berkeley

Building self-sufficient food, energy and water systems

Tribal lands have the potential to create sustainable, self-sufficient systems for providing food, energy and water to their residents, Agogino said. The U.S. encompasses roughly 70 million acres of tribal lands — about the size of North Dakota. Agriculture is the primary economic foundation for more than 200 tribes, and there is a country-wide movement to empower tribes with food sovereignty through gardens, local farms and tribal farms. In addition, tribal lands contain approximately 5% of all renewable energy resources in the U.S. Finally, creating self-sufficient agricultural and energy systems also requires water to grow food and operate energy systems.

“To solve these challenges, it is important to consider the integration of food, energy and water on tribal lands from a systems perspective that integrates Indigenous knowledge and science with cutting-edge advances in technology,” Agogino said.

The Native FEWS Alliance also seeks to incorporate Indigenous thinking and approaches into Western science education. Indigenous approaches are often rooted in holistic thinking, recognizing that food, energy and water systems are all deeply interconnected, and that one cannot be addressed without considering the whole. These approaches also stress the importance of building trusting relationships with impacted communities and working alongside them to identify appropriate solutions.

“Native cultures have a long history of long-term environmental sustainability and systems thinking when it comes to food, energy and water,” Agogino said. “We want to take some of these Indigenous research practices and use them to transform our own curricula to make it better for all students.”

Through the application of culturally-relevant approaches, the alliance is developing curricula and mentoring guides, offering workshops, adapting and adopting best practices and sharing the results. For example, the University of Colorado is leading a certificate program in Native Food, Energy and Water Systems, along with micro-credentials in topics like tribal governance or participatory decision-making.

“The results of this training and research will be strengthening our domestic workforce, decreasing our dependence on foreign produce and energy, and advancing economic prosperity in Native communities,” said Yael Perez, director of the Development Engineering Program at UC Berkeley’s Blum Center for Developing Economies and program director for the Native FEWS Alliance. “The skills that our graduates acquire also have the potential to be applicable to other FEWS-challenged communities around the globe.”

Since 2008, Agogino and Perez have collaborated with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation near Ukiah, California, to design housing and renewable energy power systems for the community. Their work in the alliance builds upon the lessons they have learned from this partnership, as well as from UC Berkeley’s development engineering programs (DevEng), which teach students how to develop technical solutions to meet the needs of low-income communities.

As part of the alliance, Perez was working with professor Peter Romine, from Navajo Technical University, to create an indigenous engineering program for Navajo Tech students. And last fall, UC Berkeley offered a course on writing and communicating developmental engineering projects as part of the alliance’s certificate program.

Diego Moran/UC Berkeley

Fostering ethical, community-oriented research

At UC Berkeley, the Native FEWS Alliance hires two graduate student researchers (GSRs) each year to connect with students on campus and select speakers for the Indigenous Research Methods seminar, which they call the Indigi-Grad workshop. Past GSRs include McKalee Steen, who is studying Native land reclamation and its social and ecological impacts; Breylan Martin, who is studying repatriation and the continuation of Native cultures; Natasha Beepath, who graduated with a master of public policy degree in spring 2024; and Sydney Moss, who graduated with a master’s degree in development engineering and is now a Ph.D. student in environmental science, policy and management.

Marlena Robbins, a third-year doctoral student in public health at UC Berkeley, is currently a GSR along with D’Angelo. For her dissertation, Robbins is studying the rise of psychedelic-assisted therapy in the U.S. and how Native American communities are being impacted by the decriminalization of psychedelic substances.

As a young person growing up on the Navajo reservation in Windrock, Arizona, Robbins said that attending a leading research university like UC Berkeley was never on her radar.

“Science classes are not as well-equipped on the reservation, so going to a school like Berkeley was not really marketed to us or supported by the public education system,” Robbins said.

At UC Berkeley, the Native FEWS Alliance has given Robbins a sense of belonging and connected her with other students and scholars who share her mission of doing ethical, community-based research.

“I think the Indigi-Grad workshop itself as a learning hub that is very intentional about the researchers that we bring in,” Robbins said. “We are very serious about inviting people that are dedicated to doing ethical work, strengthening Indigenous methodologies and having a positive impact on tribal communities.”