Legacy of Chiura Obata, artist and former UC Berkeley professor, endures on campus

Obata, detained in a World War II internment camp for people of Japanese descent, urged turning to "Great Nature" to transcend differences and difficulty.

June 11, 2025

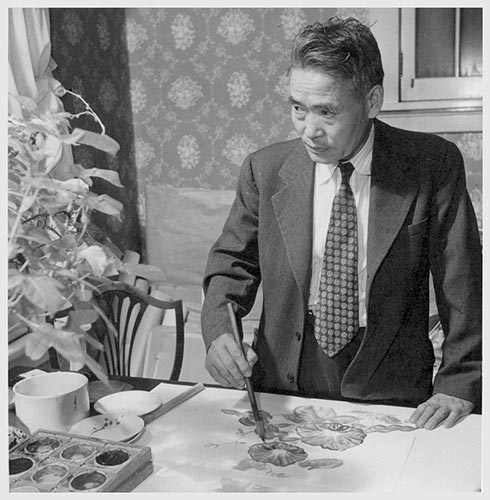

Photograph by Randy Dodson, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

As a child, Kimi Hill had seen the sketches that her grandfather, the well-known artist and UC Berkeley professor Chiura Obata, made while in World War II internment camps. But the artwork sat in storage, as quiet as the adults who never spoke of his incarceration.

“For many of my generation, we didn’t know anything because no one told us anything,” said Hill, now 70. “There was so much trauma and shame associated with being forced into the camps that parents generally didn’t want to talk about it.”

After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, U.S. Presidential Executive Order 9066 mandated that some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry leave their homes, jobs and schools for confinement in 10 camps. Among them were 1,300 Berkeley residents, including Obata and his wife Haruko.

Gretchen Kell/UC Berkeley

Decades later, in the 1970s, Obata’s wartime art was first exhibited. Hill, then a teenager, aimed to know her maternal grandfather better. But in 1970, when she was 15, he suffered a series of small strokes and lost his ability to speak English.

Today, however, Hill is the family historian and well-versed about Obata, who met both artistic acclaim and blatant prejudice after arriving in the U.S. in 1903 as an aspiring 17-year-old artist. She and her sister Mia Kodani, 71, share his legacy in local classrooms and at historical societies, libraries, museums and at Berkeley, where Obata taught for 20 years.

Hikaru Iwasaki for the War Relocation Authority

Last month, Hill and Kodani — East Bay residents with art degrees from Berkeley — led a tour on campus of Obata’s favorite places to paint and teach, including Faculty Glade, where old California live oak trees have picturesque, horizontal branches. “He loved painting those,” said Hill, as well as eucalyptus trees, which “required different brushstrokes.”

Hill shared bits of Obata’s life story, which she began researching at the request of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History for its 1987-2004 exhibition, “A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution.” Years of talks with her grandmother, an artist skilled in ikebana, Japanese flower arranging, helped. In 2000, the book Topaz Moon: Chiura Obata’s Art of the Internment was published, with Hill as editor.

Among the more than 500 artworks that Obata created while detained is the 1942 “Moonlight Over Topaz, Utah.” The painting — like much of his life’s work — conveys Obata’s vision of what he called “Great Nature,” which helped him transcend the harsh conditions of his imprisonment at the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno and at Utah’s Topaz War Relocation Center.

In the painting, dark barbed wire fences, a water tower and barracks appear tiny, insignificant and hidden behind layers of soft, early morning mist. The viewer’s eye instead heads to the distant purplish-blue mountains, some with snow, and to the bright white moon.

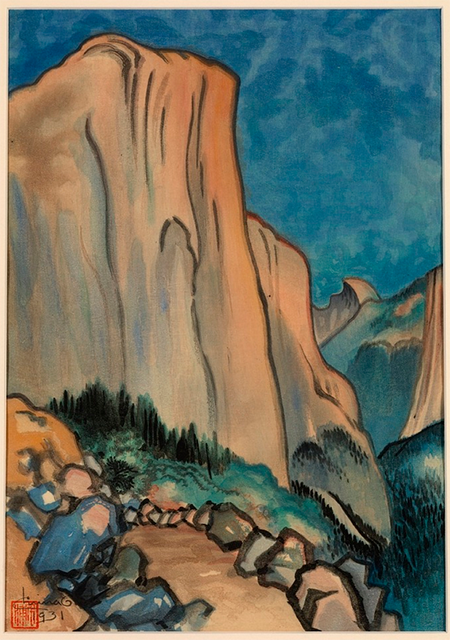

Obata’s art frequently includes the moon — a symbol for him, said Hill, of hope, eternity and peace. His popular “Evening Moon at Yosemite, California” includes a crescent moon. He first visited the national park in 1927, producing more than 100 drawings over six weeks and pronouncing the trip “the greatest harvest for my whole life and future in painting.”

“Despite all the institutionalized racism against him,” said Hill, “Obata was an artist with such a deep connection to this amazing landscape in California, where he was able to find and appreciate this powerful experience of natural beauty. He didn’t feel he was not supposed to be here, even when people told him, the government told him, ‘You don’t belong here.’”

(Chiura Obata, Lake Basin in the High Sierra, 1930, color woodcut on paper, image: 11 3/8 x 15 5/8 in. [28.9 x 39.7 cm], Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Obata Family, 2000.76.25, © 1989, Lillian Yuri Kodani)

Obata’s presence on campus

Obata also had a deep connection to UC Berkeley, where he began teaching in the Art Practice Department in 1932. Over his 20-year career, the popular professor instructed some 10,000 students in traditional Japanese ink painting, or sumi-e, and painting on silk.

Beyond technique, he taught them to observe and appreciate nature’s beauty, taking them outdoors to note the changing seasons. “No one should pass through four years of college,” he once said, “without being given the knowledge of beauty, and the eyes with which to see it.”

Obata considered his style of painting a way to share “the depth and presence and power of the natural world that is here, if you can open your eyes and really see,” said Hill. “He wanted to share that with people here, young people, in particular, and as a teacher, that was a way of fulfilling a dream for him.”

Obata even taught at Tanforan and Topaz, setting up art schools for hundreds of his fellow detainees. Friends, Berkeley students and museums donated supplies. On New Year’s Day at Topaz in 1942, Obata asked his students there to strengthen themselves by looking outside, beyond their plight, at “the beautiful mountains. They can’t be moved no matter how many people try.

” … We only hope that our art school will follow the teachings of this Great Nature, and that it will strengthen itself to endure like the mountains, and like the sun and the moon, emit its own light.”

At Berkeley, Obata’s artwork hangs in buildings including Anchor House and the Faculty Club. The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive has 75 of his artworks, 14 of them are large ink on silk paintings brought there last year from California Hall. Obata-related materials are among the Bancroft Library’s holdings.

Archival documents detail an effort in 1942 by then-UC President Robert Gordon Sproul and then-Vice President and Provost Monroe Deutsch to secure a safe harbor for the Obata family in Yosemite. But it failed.

“In war time, … we would not think of requesting permission for such persons to stay in Yosemite National Park,” Frank A. Kittredge, Yosemite’s superintendent, replied to Deutsch, who relayed these words to Obata in an April 16, 1942, letter. Deutsch added, “It is a source of the very deepest regret to me that an answer of this type has come. … I do hope that some other solution to your problem can be worked out.”

Courtesy of the Estate of Chiura Obata

But Obata had no choice: The family soon abandoned their home and art supply store. Some of Obata’s artwork was sold to establish a scholarship for any art student, regardless of race or creed. Sproul offered to store many of Obata’s remaining paintings until the war ended.

On the recent tour, Hill and Kodani also pointed out the First Congregational Church of Berkeley, across from campus, where the city’s Japanese Americans, including Chiura and Haruko Obata and two of their children — the third escaped internment by transferring from UC Berkeley to Washington University in St. Louis — were taken into U.S. Army custody in early May 1942 and placed on buses bound for a detention camp.

In 1945, Obata returned to his faculty position and retired in 1954, the same year he and his wife became naturalized U.S. citizens, having been prohibited by law until 1952.

Eleanor Breed

What would Obata say about today’s political turmoil?

For Claudia Polsky, a professor at Berkeley Law, “Obata has always been everywhere at Cal; in his artwork framed in the reception area of the Faculty Club; in the drawings he did of many places on and near campus, including the church sidewalk from which he and Japanese American students and staff were forcibly removed.”

“I share these drawings with my students,” she said, “and carry his images in my head as I wander campus paths and recall his depictions of place.”

Courtesy of the Estate of Chiura Obata

This spring, at a campus rally, Polsky recalled Obata’s internment in a speech to the crowd. She was among the researchers and students protesting ongoing and threatened cuts to federal research funds by the Trump administration, which also is vowing to carry out “the largest domestic deportation operation” in U.S. history.

She told of Obata’s forced removal from Berkeley in 1942, and that of hundreds of others of Japanese descent in the campus community, including 500 students whose education and participation in graduation ceremonies were cut short.

“We can’t let this happen here, or anywhere,” urged Polsky. “Not now, and not ever.”

When asked what Obata would say about the current U.S. government’s accelerated efforts to deport immigrants, Hill quickly replied, sure of what her grandfather would say.

“In spite of what is happening with world problems or personal problems,” said Hill, “he just felt you had to find your source of strength and inspiration through a real connection to the natural world. That’s what worked for him. That’s what brought him through everything in his life.”

Jennifer Monahan for the Division of Arts & Humanities, UC Berkeley College of Letters & Science

Obata’s idea was “that Great Nature … transcends everything. It transcends nationality; it transcends politics,” Timothy Anglin Burgard of the de Young Museum said in a 2013 interview, adding, “His concept of Great Nature as a common ground that is shared by all cultures and that deserves respect and protection … seems more prescient with time.”

Today, Hill said she understands and appreciates her famous ancestor “in a way I never did before,” as well as the places in nature that he loved, and that she loves, including Bay Area scenery, the California coast, and Yosemite and the High Sierra.

“Now, we totally get each other,” she said, adding, “We really like each other.”