Keynote speaker to grads: ‘We win if your mind is stretched, but not filled’

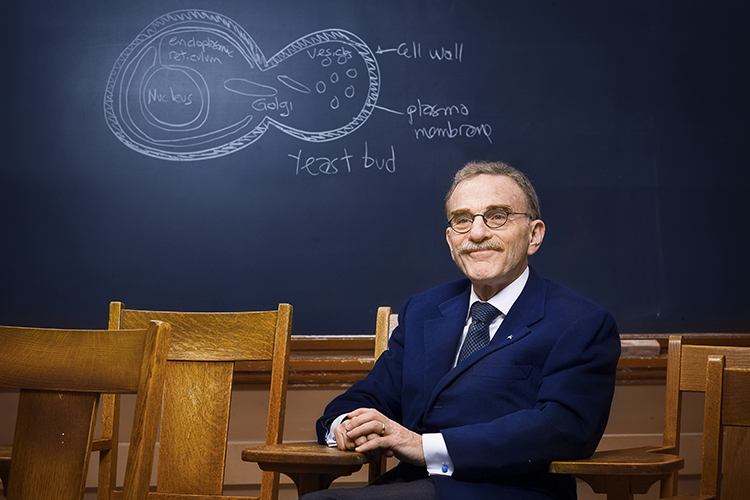

UC Berkeley professor and 2013 Nobel Laureate Randy Schekman gave the keynote address at UC Berkeley's 2022 commencement ceremony.

May 14, 2022

UC Berkeley professor and 2013 Nobel Laureate Randy Schekman gave the following keynote address at UC Berkeley’s 2022 commencement ceremony.

Welcome to graduation, my favorite activity of the year. Many people from my generation didn’t attend such ceremonies because they were considered too conformist. Of course, I have made up for that almost every year of the 45 I have been on the faculty at Cal, including one year where I was able to introduce my parents, whom I had deprived of my college and Ph.D. ceremonies. Over the years, I have witnessed beach balls being tossed around the Greek Theatre, Haas Pavilion and Zellerbach, a cacophony of air horns, raucous cheering sections, graduates parading across the stage wearing virtually nothing under their robe and students doing back flips across the stage (though not both at the same time, at least not yet).

Congratulations! Most of you are now free to dump all those random facts that you crammed in as recently as a week ago. The operator’s manual that comes with your new degree does not call for you to remember the names of the nine muses, the quadratic equation or the order of the planets, as Billy Collins memorably noted in his poem, “Forgetfulness.” The fact that ATP is the energy currency of your cells is but a fleeting memory jumbled together with the parties and laughter and, regrettably, the isolation that no doubt filled your days and nights these past four (or five) years.

“I wish also to honor those among us who have taken that long journey to arrive at this moment,” Schekman told graduates. (UC Berkeley photo by Keegan Houser)

So, what was Cal all about, other than as a means to deliver you to the next station in your life: law school, medical school, graduate school or work? We like to think you learned something more than the mere facts that filled the hours of lectures and reams of notes. As you walk away from this ceremony, consider where you are now, compared to your first days at Cal. If we succeeded, you are now more critical of facts and sources. You will question the truth of common wisdom and ask for the evidence that supports a broad assertion. When a drug company boasts of some new wonder cure, you will remain skeptical unless the facts and controls are spelled out. When you read about a new discovery, you will want to know what we learned or how a process is more deeply understood and not simply the practical value of the findings. You will not accept on authority the word of some big shot professor, even a Cal Nobel laureate, and certainly not a Stanford professor, if he or she uses his position to espouse some unsubstantiated nonsense. We win if your mind is stretched, but not filled.

And what keeps us going, those of us who do need to remember the amino acids and the genetic code? Why do we fight the battle for research funding, tenure, endless repetition of the same lecture material, and many of the same questions and concerns about extra points on the regrades? It’s the certain knowledge that we will witness year in and year out the same thrill of understanding displayed on your bright young faces as you march in and out of our classrooms and offices. It is the magic of discovery when a research student is the first to realize some new principle that shines a tiny light on an unexplored corner of a cell, or to discover and translate a new text, or to reinterpret a well-known bit of history.

We keep going because those before us made this institution the finest public university in the country, and it is our obligation to pass this on in even better shape. We do this because the University of California has provided generations of middle- and working-class families with an opportunity to build a better life. The elite private universities consider their middle class to be families with an income of as much as 200K a year. But 70% of college students in the U.S. attend public institutions where family income is much closer to the overall national average. The real world comes to Cal!

Randy Schekman, professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley, won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. (UC Berkeley photo by Elena Zhukova)

I’d like to share with you an example of how public education, in this case in Eastern Europe, served to raise a young woman from poverty to the heights of achievement with the key discovery that has saved millions of lives in the current pandemic. This is the story of Katalin Kariko, a Hungarian emigre who made the breakthrough discovery that led to the development of the mRNA vaccine so many of us have taken to protect against coronavirus infection. Katalin grew up in a home without running water, a refrigerator or television, but with an aspiration to rise above that with an education at the University of Zagreb and a postgraduate degree in biomedical science. Trapped behind the Iron Curtain, she sought refuge in the west and escaped with her husband and young daughter and a teddy bear stuffed with cash she collected from the black market sale of her car. She landed in the U.S. and began a vagabond journey through various academic institutions until she landed a non-tenure track position at the University of Pennsylvania. There, she hoped to realize her dream of a therapeutic application of mRNA, the message copied from genes housed in nucleus of our cells. mRNAs carry a copy blueprint needed to construct all the protein molecules cells need for life. The plan was to inject an mRNA that would allow cells to produce a protein of clinical importance in treating disease. The problem is that mRNA molecules injected into an animal elicit an inflammatory response that makes them toxic and useless as a therapy.

After years of struggle, she failed to gain acceptance and funding for her idea and was dismissed from the university with little prospect of employment. Fortunately, a sympathetic colleague at Penn, Drew Weissman, gave Katalin a second chance with a lab bench and a collaboration that finally overcame the problem of mRNA toxicity. The team found that some RNA molecules, those that have a variety of chemical modifications, manage to evade the immune system and are safe to inject into an experimental animal. By a trial-and-error test of the various chemical modifications, Kariko and Weissman discovered that one specific molecular change was enough to hide mRNA from the immune system and allow mRNA molecules to be injected for potential therapeutic application. Despite what we now appreciate as a revolutionary discovery, her work was rejected at the most so-called prestigious journals, but was instead published in the journal of a scientific society. Seeking an opportunity to apply her discovery, Katalin returned to Europe to join a fledgling biotech company that didn’t even have a website. In collaboration with two Turkish immigrants to Germany who started the company BioNTech, and with financial support from Pfizer, the team launched the vaccine simultaneous to the American effort at Moderna, and the rest is history.

In the time since just after the launch of the vaccine, Kariko’s role was finally recognized, and she has been celebrated, along with Weissman, around the world with dozens of major biomedical prizes, almost certainly to include the Nobel later his year. I had the pleasure of introducing Katalin at a recent drug discovery symposium, and in the Q&A after her talk, I asked how she dealt with the all the adversity she faced in her life and in gaining acceptance of her ideas. Katalin remained upbeat throughout and was sustained by the courage of her convictions. In a response that I shall never forget, she said that, after all, “I had my own lab bench and was in the United States of America.” With all that we have faced in the xenophobic reaction to immigrants in this country, her courage and the simple confidence of the statement, “I had my own lab bench and was in the United States of America,” must resonate with many of you here today.

I wish to salute the many other immigrant stories we have here today. Let me begin with my life partner and colleague, professor Sabeeha Merchant, who is with me here on the stage, and her mother, Sharifa, out in the audience, who emigrated from India so that Sabeeha and her brother could realize the benefit of great public education at the University of Wisconsin. My grandparents on both sides of my family escaped the pogroms of Eastern Europe to achieve their dream of religious freedom and opportunity that made it possible for me to be here today.

I wish also to honor those among us who have taken that long journey to arrive at this moment.”

I wish also to honor those among us who have taken that long journey to arrive at this moment. May I please ask those of our graduating seniors who are the first in their family to attend college to stand and be recognized? And now their proud families? May I now ask those of you here on Pell Grants, recognizing merit and financial need, to stand and be recognized? And now your families? You are the reason the University of California is also the most important institution of higher education in the country. The private universities that cater to privilege and entitlement can’t hold a candle to you and what you have accomplished to reach this milestone.

My journey was made possible by inspired investments in scientific research and public higher education. A key inflection point in the 20th century history of American scholarship in science can be traced to a transformative report, “Science: Endless Frontiers,” written by Vannevar Bush, the science adviser to Presidents Roosevelt and Truman. He wrote, “Scientific progress on a broad front results from the free play of free intellects, working on subjects of their own choice, in the manner dictated by their curiosity for exploration of the unknown. … Freedom of inquiry must be preserved under any plan for government support of science.” Opportunities for education in public universities exploded in the 1960s. The race to space initiated by Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy led to a substantially increased federal investment in science and science education. In California, Gov. Pat Brown and Clark Kerr, his visionary leader of the University of California, created a master plan for higher education that included the construction of new campuses large enough for the children of all the families of our state to enjoy the nation’s finest educational opportunities.

I was a direct beneficiary of that investment. I came from a middle-class family where college was an expectation, but money was a concern. No private school for me. But UCLA was great. I paid $270 in fees for my freshman year in 1966, and my room and board at the student co-op amounted to no more than $800 a year. I paid $6.25 for season tickets to watch the Bruins win three national basketball championships in a row under the towering leadership of John Wooden and the legendary talent of Kareem Abdul Jabbar.

As a freshman, I learned chemistry from Willard Libby, a Cal Ph.D. Nobelist who invented C-14 dating of ancient biological materials. Working in a research lab as an undergraduate at UCLA stoked my passion for science as a path to discovery of basic cellular processes. I worked a summer job and earned enough to cover my fees, room and board, and books for the full year. My father paid next to nothing to send five children through college. At least 80% of the University of California budget at that time was covered by the state, compared to a meager 10% today.

Our great public universities continue to educate the majority of our nation’s future scholars, scientists and engineers.”

Our great public universities continue to educate the majority of our nation’s future scholars, scientists and engineers, but the nature of that education has regrettably evolved from a public good to a private commodity, funded to an alarming extent by burdensome personal debt. The leaders of our public institutions scramble for resources to provide scholarships for students who in my generation enjoyed an essentially free education. Who will provide the resources to invest in science and research so those students can continue to have a first-class education on par with what they would receive at a private institution?

The United States flourishes due to a unique mix of public and private universities that is the envy of the world. I have remained a faculty member here at Berkeley for over 45 years, in part because public universities are the most effective engine of social mobility in our society.

At Cal, we lead the nation in elevating students from the lowest 20% of the economic spectrum to the top 1%. And yet, now it costs more for a middle-class student to attend Cal than to attend an elite private university. We owe it to our families, to your younger brothers and sisters, to your children and grandchildren to reverse this trend so that members of future generations will have access to the same outstanding UC education that you and I have enjoyed. GO BEARS!