Author Charles Yu: ‘Interior Chinatown’ is about roles and how we play them

Incoming UC Berkeley students read the 2020 novel, which goes inside the mind of a young Asian American man trying to make it in Hollywood

August 24, 2022

Follow Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast about the people and research that makes UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is. Review us on Apple Podcasts.

See all Berkeley Voices episodes.

In this episode of Berkeley Voices, Charles Yu discusses his 2020 book, Interior Chinatown, which goes inside the mind of a young Asian American man trying to make it in Hollywood. Incoming UC Berkeley students read the book over the summer as part of On The Same Page, a program from the College of Letters and Science, so they’d have something in common to talk about throughout the year — socially, in classes and at events designed to explore the book’s themes.

“I hope that people can see that, in one way or another, all the characters in this book are wearing a mask and a costume, to some extent, and they don’t fit them perfectly,” said Yu. “And we, hopefully, see the ways in which the person underneath peeks out and can’t be fully covered by what’s there. In those moments … real connection can come about.”

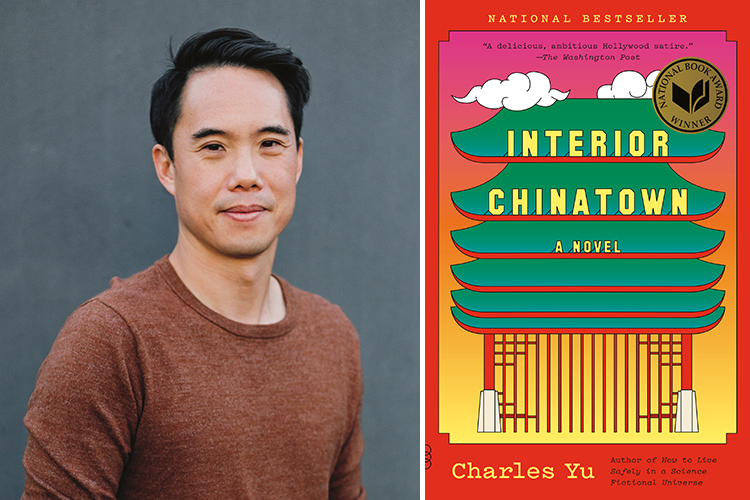

Charles Yu is the author of the 2020 book, Interior Chinatown. This year, all incoming first-year and transfer students read the novel as part of On The Same Page, a program from the College of Letters and Science. (Photo by Tina Chiou)

Intro: This is Berkeley Voices. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: “Palms Down” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Narration: As a kid growing up in Los Angeles in the 1970s and ‘80s, Charlie Yu watched a lot of TV. A child of Taiwanese immigrants, Charlie especially loved shows and movies starring famed martial artist Bruce Lee. His favorite was the 1972 film, Fist of Fury.

Charlie Yu: One of the few ways that you could interface with Asians or Asian Americans in U.S. TV and film was through martial arts. That was one of the few universally positive role models that an Asian American kid of that generation would have had. There were no, like, real actors or professional athletes or other public figures, you know, in the [mainstream] consciousness. But Bruce Lee was sort of universally known and universally cool.

Narration: Most of the time when he saw Asians or Asian Americans on TV, they were playing stereotypical or flat characters, sometimes offensive, sometimes not.

Charlie Yu: But largely, it was just an absence. Growing up, watching way too much TV. Like, I was a heavy, heavy consumer of television as a kid, and probably, the invisibility did as much to affect me as the visibility. And so, you have both sides — not seeing it, and then seeing very infrequent portrayals would put a lot of pressure on those portrayals, and so, there’s that experience.

[Music fades out]

Narration: Charlie is a Berkeley alumnus. He graduated in 1997 with a major in molecular and cell biology and a minor in creative writing. He’s a screenwriter for TV and film and he’s the author of several books, including the 2020 novel, Interior Chinatown, for which he won the National Book Award for Fiction.

In Interior Chinatown, the main character is named Willis Wu. He’s a young Asian American man trying to make it as an actor in Hollywood. For Willis, playing Kung Fu Guy — someone akin to Bruce Lee — is his ultimate dream. But he feels stuck, playing characters that he refers to as Generic Asian Man roles.

At Berkeley, all incoming first-year and transfer students got a copy of Interior Chinatown to read over the summer, so they’d have something in common to talk about with each other throughout the year — socially, in classes and at events designed to explore the book’s themes. It’s part of a program from the College of Letters and Science called On The Same Page.

[Music comes up]

Recently, I spoke with Charlie about Interior Chinatown, how the best conversations can happen when we least expect them and how it feels to be coming back to the Berkeley campus.

Anne Brice: First, I was wondering if you could explain the title, how you came to it and what it means for the story?

[Music fades out]

Charlie Yu: Well, I mean, probably some people know, and for those who don’t, there’s the convention, when you’re writing a script for TV or film, of either interior or exterior is the first thing you write at each scene. It’s called the slug line. On some level, it’s just a very basic heading of, like, are we inside or outside? It tells production, do we shoot this inside or outside, which has a lot of difference for timing, sunlight, elements, that sort of thing.

But it turned out to be one of those things where it was a metaphor, a way into a lot of things that were interesting. I wanted to tell a story about the interior life of this character, Willis Wu. And so, it kind of dovetailed nicely with that.

Anne Brice: Can you describe what Interior Chinatown is about? And also, the main character, Willis Wu — what’s his driving force? What is he after?

Charlie Yu: Right. Yeah, in a nutshell, I guess this would be the Hollywood elevator pitch, is imagine an episode of, like, a police procedural, like Law and Order or CSI. And the cops, in the course of an episode, will usually go question a number of potential witnesses or, you know, suspects, people of interest. Often in those scenes, someone will get a very brief cameo, one line [or a few lines or, at most], they’ll play a very marginal part in the story.

The example I always go to is, there’s just a guy who’s, like, unloading a van while the cops question him about what he might have seen. And so, this is really a story about that guy who’s unloading a van.

That’s kind of the setting for this story, is the idea of these characters — who normally wouldn’t have an extended plot line or be regulars on the show — what is their life like when they’re not being questioned by the cops? Like, sort of imagine dimensionalizing the life and experience of a background character.

That’s really what Willis Wu is. He’s a background Asian guy who doesn’t get his own storyline. So, this book is trying to sort of see what it’s like to be him, you know, get into his consciousness. And that, again, circles back to the title, [to the idea] of giving interiority to a character like that.

Anne Brice: For Willis Wu, what does he want most of all?

Charlie Yu: You know, what he wants at the beginning of the book — it changes over the course of the book — but what he wants at the beginning is to be Kung Fu Guy. That’s what he wants. That role.

Anne Brice: Can you describe what Kung Fu Guy is? Or who he is?

Charlie Yu: Yeah. Kung Fu Guy is, in the world of this novel, it’s the slot that’s reserved for the special guest star every season or so, who is really good at martial arts and gets to be cool. Willis knows that if he has a shot at success, that’s kind of the path, [his best-case scenario], to try to be that.

[Music: “Curious Case” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: He [Willis] goes back and forth a lot, with what’s happening in his interior, in his mind, and kind of narrating what’s happening and then it goes to the script and the show that he’s on. I was wondering why you chose that narrative style.

Charlie Yu: The narrative style is, at times, I’d say, confusing — intentionally so. It was a kind of intuitive sense of, OK, there’s a kind of rule at the beginning and then very quickly kind of starting to bend or even break the rules, even internally.

And so, what’s happening, in terms of this narrative style, is that there’s literally a script. It’s written as a screenplay. And Willis doesn’t really have lines at first in the screenplay. He’ll have like one or two lines, and then he has these kind of asides or thoughts or interior monologue.

And what happens in the course of the story, because he’s getting drawn into the plot, is that he [Willis], increasingly, has actual lines to say in the show. And what starts to happen, I think it becomes very blurry as to, are we in Willis’s head, or is this actually happening in a way that everyone else understands it?

Spoiler: I would say there’s no real clear answer to that, in most cases where it is unclear, because that’s kind of the point. I think we’re in a very interior space here, where if people want to try to get a grasp on it, you could think of Interior Chinatown as kind of like a movie set, but also like a mindset, as well. We’re in a psychological landscape to try to portray what it’s like to be marginalized in the way Willis and his family and the other people in his community feel.

Narration: There is one part in the book that kind of breaks from this narrative style. It’s almost like a short history lesson on the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which was a 10-year ban on Chinese laborers immigrating to the country. It was the first significant law restricting immigration into the U.S.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: This part, it was brief and to the point, but very arresting. And so, I was curious why you included that and what you hoped people felt from it or understood or learned from it?

Charlie Yu: Yeah, I like to, you know, sneak in the veggies. (Laughs) You know, I learned about it first at Berkeley in Asian American Studies 20A — the intro class opened my eyes and introduced me to a lot of things for the first time. I also went to law school. I was a lawyer for a number of years before turning to writing full time. And so, I really felt like I had to amortize my legal education, put it to some use.

I mean, I think Willis is, at the beginning of the book, kind of adrift or feeling stuck, feeling very much in his own head. And I think part of what he does in the course of the book is he gets exposed to the system that he’s part of. And part of that system has a history to it.

And I think the [Chinese] Exclusion Act, for instance, when I learned about it and as I continue to kind of learn and think about, it’s not something that I was conscious of until college and into adulthood, but it has had an effect on… and we continue to feel the effects of that. Right? The Exclusion Act was [initially] passed in 1882, and it didn’t actually fully get undone until 1965. It was technically repealed in ‘43, but until ‘65, the [very restrictive] quotas were still in effect.

So, it was 80 years, over 80 years. And we’re really only two or maybe three generations out from the huge change that happened post ‘65 — my parents are post-‘65 immigrants — and that continues to shape a lot of things that are happening now in ways that I don’t pretend to understand fully.

[Music: “Nothing Nothing At All” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: Willis is playing all these background characters, and he’s kind of working his way up, and he’s waiting for this big break. And then, later in the book, his co-star tells him that, you know, working your way up in a system, or being part of a system and trying to get ahead and go up and go forward, doesn’t mean that you’ve beaten the system, but that you’ve bought into it. And so, I’m wondering if there’s a moment where he realizes that he’s… this is within me, too, and I’ve internalized it somehow?

[Music fades out]

Charlie Yu: Yeah, I think I was trying to get at a number of things, you know, or help Willis get to a number of things in the course of the book. It’s a bit of an education for him, right? It’s, I think in a lot of ways, a coming-of-age story. And one of those things is, as you are pointing out, it’s kind of a larger consciousness of being in a system and understanding that there can be a trade-off, in that in order to succeed, he’s got to sort of reinforce the system itself. Right?

And I think for me, I understand that as a kind of lesson or received assumption for, you know, I’ll speak for myself as a kid growing up, is there are certain paths: education, go to a place like Berkeley and follow a number of career paths that are acceptable or prestigious or will sort of allow you some economic upward mobility, probably social standing to some extent, and ultimately maybe a kind of cultural assimilation.

And I think, the question then is like, in doing that, what’s left behind? Or what is lost, what can be lost? It doesn’t have to be, but what does that entail for a lot of Asian Americans who are either immigrants or offspring of recent immigrants, to sort of try to enter spaces or systems that historically may have excluded either them and/or definitely excluded other communities of color?

And so, what does it mean for someone like Willis? Who does he model himself after? Or how does he think of his place in that kind of system? And what invisible trade-offs or other costs might there be to successfully assimilating, basically?

[Music comes up, then fades out]

Narration: During the story, Willis falls in love with a co-star, Karen Lee, and they get married and have a child together. Eventually, Karen is offered her own show and a part for Willis. But Willis can’t bring himself to give up his dream of becoming Kung Fu Guy. So, he lets his wife and daughter move away, and he stays behind to keep pursuing the ultimate role.

And after five years, he finally gets offered the part. He’s going to become Kung Fu Guy. But when that happens, he realizes he has been overlooking the real, most important role in his life: being a father to his daughter. So, he drops everything to begin to build a relationship with his 5-year-old daughter, Phoebe.

Anne Brice: The moment with his daughter, when they’re sitting there, it just seems really natural, really sweet. I notice that people, when they have kids, and they write dialogue for kids, it’s always so realistic because they’ll, like, ask a question that’s super, super deep, and then you give them one line, and you’re going to keep going, and then they’re like, “Anyway, I’m kind of hungry now.”

You know, they’re figuring things out, and you just try to answer them, but it’s like they don’t really want the full thing. They just kind of want to know a little bit and then, they’re so curious about, like, the next thing.

Charlie Yu: Yeah, a lot of the most memorable and honest conversations of my life have been, like, right before bedtime when I just want to get to the other side of 7:30 p.m. — “Please, go to sleep” — and I’m lying on the ground. My kids are past this age now, they’re teenagers. But, you know, lying on the ground, just trying to limp to the finish line and then having an incredibly funny or deep or surprising conversation with a small child. And that continues on in different ways.

And just like you said, they’re figuring things out and the mix of innocence, and then, as knowingness kind of creeps into that innocence, it can be both, for me, poignant and revelatory and also, it can be, yeah, so surprising, but also, cause me to just really see the world in new ways.

And so, some of that flavor, you know, it’s just like I literally stole things from my kids’ mouths and put them in the book. They’re the best writers, you know, as a kid between, I don’t know, 3 and 12. After 12, then it’s different. Other things are going on.

I think for Willis, that’s kind of the ultimate role is, not to say that someone couldn’t do this without being a parent, but for him in his story, he shifts away from a self-centric worldview when he has to take care of someone other than himself.

And, I think, in the specifics of this story, I think things are possible for his daughter that weren’t possible for his parents, for instance. He’s a bit in between them. But there is another act to this story that he will never really fully be able to understand because things are going to be so different for her. But also, maybe some things will be the same, you know, and negotiating or thinking about that tension of, like, she still looks like she looks, but she’s even one more generation removed from country of origin, whatever that means for someone like his kid.

So, I guess all of that was, you know, why it felt like the right place is, Willis’s story is not ending, but it’s transitioning into a different role, and then, his daughter’s story is really starting.

Anne Brice: Are you going to write another book with his daughter as the star? (Laughs)

Charlie Yu: (Laughs) I hadn’t planned on it, but now that you said that, I kind of want to.

Anne Brice: Oh, my gosh, I would read it in a second.

[Music: “A Rush of Clear Water” by Blue Dot Sessions]

For On The Same Page, all the incoming students are reading, have read, will read your book. What kind of conversations do you hope that it sparks? Yeah, what do you hope that people get out of it and take with them and maybe apply to their lives in some way?

Charles Yu: Yeah — it’s exhilarating and terrifying to think about all the people that are going to read this. You know, I really hope that it does, for some people, they could recognize some feeling or part of their experience. You know, whether that’s having felt like an outsider in certain ways that maybe match with Willis’ empirical experience.

But I hope, also, in a more universal sense that, you know, this is really a book about roles and how we play them. And sometimes they are fundamental to who we are — taking care of aging parents that Willis does, or being a good friend or partner — but also how roles can often be very limiting or reductive and, sort of, the people underneath those.

I hope that people can see that, in one way or another, all the characters in this book are wearing a mask and a costume, to some extent, and it doesn’t fit them perfectly. And we, hopefully, see the ways in which the person underneath peeks out, you know, and can’t really be fully covered by what’s there. In those moments, when the mask slips and you talk out of character or, you know, you’re lying on the ground talking to your kid, delirious with sleep deprivation, those moments of real connection can come about. More than anything, I hope it entertains people and makes them feel or think something that surprises them.

I’m not just saying this, Berkeley was a really special time and it was, I mean, I wish I had made better use of my time there, but the idea of taking classes with people that teach there and the students and the other community members and just the books you get to read, it’s an incredible honor to actually be part of this program and to get to talk to you. And so, I just want to say how appreciative I am. It’s really surreal to get to be coming back in this way. It’s really exciting.

Narration: Charlie Yu will be in conversation with Berkeley professor and playwright Philip Gotanda on Aug. 26 as part of On The Same Page. The event is free and open to the public. The talk will be available to livestream for 14 days after the event to Berkeley students, faculty and staff.

I’m Anne Brice, and this is Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs at UC Berkeley. If you enjoy Berkeley Voices, follow us wherever you listen to your podcasts. You can find all of our podcast episodes with transcripts and photos on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

[Music fades out]

Listen to other Berkeley Voices episodes: