Quakes in Turkey and Syria hit home at Berkeley, where aid is underway

A new website with campus resources, fundraising and academic expertise are among the ways Berkeley is aiding those impacted by one of the century’s worst disasters.

February 14, 2023

The Turkish Student Association held a vigil at Sather Gate on Sunday, Feb. 12. (Photo by Liana Dagdevirenel)

UC Berkeley undergraduate Alp Eren Özdarendeli is unable to focus on his studies and stays awake all night hoping to reach friends and family in his hometown of Kahramanmaraş, a Turkish city close to the epicenters of last week’s devastating earthquakes.

As of Tuesday, nearly 38,000 people are reported dead across southeastern Turkey and northwestern Syria, and tens of thousands are injured following the temblors — one a magnitude 7.8, the other, which hit nine hours later, a 7.5. They’re now among this century’s deadliest disasters.

“I lost two of my middle school friends, they were home on winter break,” explained Özdarendeli, who is majoring in electrical engineering and computer sciences. “And one of my closest friends lost his whole family. Every day, I hear of someone I know who has died.

“I’ve been in shock, actually. Unable to communicate with any counselors, officials, advisers. I really feel like no one can understand what I’m going through.”

Hilal Tümer, a second-year Ph.D. student from Turkey, said she’s also been “distracted for more than a week” after she and her husband, Mehmet, a Ph.D. student in Arizona, learned of the tragedy in Kahramanmaraş. Several people in his family are injured there, and others have perished. He has returned home to help with rescues — and to plan funerals.

An estimated 100 international students on campus from Turkey and Syria, along with staff and faculty with ties to these countries, are part of the Berkeley community, which is responding with campus resources, disaster relief and academic expertise.

Two truckloads of items including clothing, diapers, blankets and health supplies, were collected for quake victims by the Turkish Student Association. (Photo courtesy of the Turkish Student Association)

The campus’s Turkish Student Association, along with other campus groups, is busy each day raising relief funds — so far, $3,500 has been gathered — at a table on Sproul Plaza. The students also held a collection, now complete, of two truckloads of clothing, diapers, blankets and health supplies that are on the way to quake victims.

“We are simultaneously devastated and moved by the outpouring of love and support,” said Mehmet Donmez, a member of the Turkish Student Association. The group also held a candlelight vigil at Sather Gate last Sunday to mourn the lives impacted by this unfolding disaster.

A website from the Division of Equity and Inclusion has launched to make students, staff and faculty aware of campus resources for trauma, tragedy and loss, with links to opportunities to join humanitarian response efforts, such as the White Helmets, Turkish Red Crescent, Islamic Relief USA and Syrian American Medical Society.

Other campus resources for students include financial support, such as short-term emergency loans, and legal assistance. Cal Student Central is a starting place for such help.

And Turkish visiting scholar Selim Gunay and engineering professor Khalid Mosalam are leading a reconnaissance team to assess the structural damage caused by the quake. They hope the work, being carried out as part of the Structural Extreme Events Reconnaissance (StEER) Network, will reveal important lessons for averting future disasters.

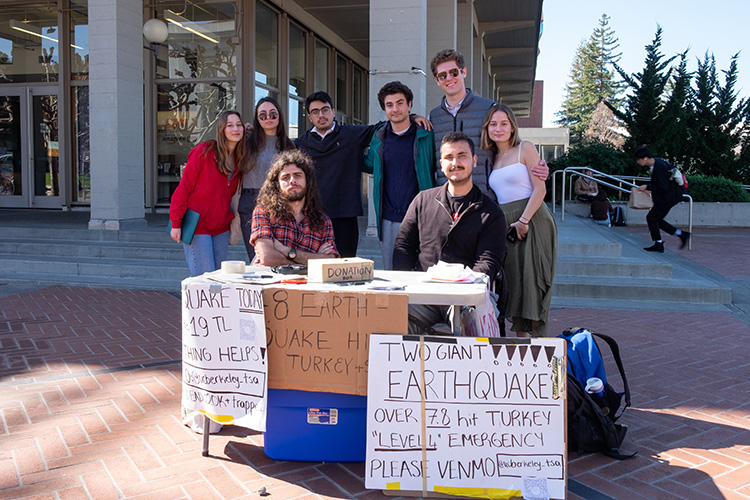

Members of Berkeley’s Turkish Student Association and International Students Association have been steadfastly collecting quake relief funds on Sproul Plaza. (UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liashcheva)

‘I can’t go on like this for the next three months’

Alp Eren Özdarendeli has lived in Kahramanmaraş his whole life and last visited just a month ago. His parents, who are gynecologists, survived the quakes. They worked at a hospital in the city’s center. But there is no more hospital, and the eight blocks of housing surrounding it where hospital employees, excluding doctors, lived, is gone, as are hundreds of people who lived there.

Since the quakes, sophomore Alp Eren Özdarendeli has prioritized checking on the welfare of his family and friends in Turkey, even if it means observing the time zone there and being awake while Berkeley sleeps. (Photo courtesy of Alp Eren Özdarendeli)

“When my parents went to the center of the city, they saw that none of the buildings remain,” he said. “The hospital is very damaged; it’s going to be demolished.”

Fortunately, during the first quake, which occurred pre-dawn, his parents weren’t at work. But Özdarendeli initially couldn’t reach them by phone. “I didn’t hear their voices for two days,” he said.

Eventually, his father was located, safe, by one of Özdarendeli’s friends. Fortunately, his mother, separated from her husband for several hours while she searched for the family cat, also survived inside their home within an 11-story building.

His paternal grandparents’ building is too damaged for them to remain there. “My uncle came and got them, and they’re living in a different city,” said Özdarendeli, whose parents also have left, for Istanbul, to live with his sister.

One of Özdarendeli’s biggest concerns is his family’s new economic situation, and what it will mean for his parents’ lives and the rest of his education at Berkeley.

He hopes to return to Turkey shortly.

“My parents only want me to focus on my studies, but I can’t go on like this for the next three months,” he said. “My friends there explain what they’re seeing, very bad things, like the sports centers filled with corpses. My former middle school is organizing to help survivors, and I would like to be there, where most of my close friends are.”

Turning pain into action

Ph.D. student Hilal Tümer outside the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque, a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. (Photo courtesy of Hilal Tümer)

The past week was one of pain, with a glimmer of hope, for Hilal Tümer.

A doctoral student in history, she grew up in Istanbul before coming to Berkeley during the pandemic to research 19th century Greek-Ottoman relations and modern migration from Greece to Turkey.

When her husband, in school in Arizona, called her with news of the first earthquake that hit his hometown in Turkey, they tried to minimize the situation, as quakes aren’t infrequent there, and to wait to hear from their families.

But gradually, news reports and missives posted on Twitter began to show the scale of devastation. Phone communication was spotty, at best. Istanbul seemed to have been spared. But what about the situation farther south, near the Syrian border? Near her husband’s hometown of Kahramanmaraş?

Then came the massive aftershock.

“I think that that was the moment I really, really understood what was happening,” said Tümer.

Her husband felt especially miserable, so midweek, she encouraged him to return to hard-hit Kahramanmaraş and do what he could to help. The couple soon learned that several people from his family had been hurt or killed.

Lately, Tümer has found herself second-guessing little moments of joy because so many other people are facing trauma.

“I’ve been distracted for more than a week,” she said. “The worst thing is you feel guilty for breathing, for eating, for having fun with your friends after the earthquake because you know so many people in your own country are under the debris right now. It’s just painful.”

But she has turned that pain into action. She’s been coordinating with professors and others to help identify reputable organizations in Turkey and Syria that will be involved in the recovery efforts for the long haul. Monetary donations are the most needed, she said, since the recovery process will be so long, and financial means — especially in Syria — are profoundly limited.

Tümer admits she’s not an overly optimistic person. But the outreach and donations that she’s seen — free from politics — have been both “humbling and gratifying,” she added.

“I am here in a country where I am not a citizen. I do not really have any formal relations with anyone except for friendship. And these people, knowing that my husband’s family is affected by this earthquake, have sent donations. They’ve sent prayers, thoughts, messages of support.

“It was, I think, one of the best feelings I’ve ever experienced in Berkeley.”

Meltem Su, president of the Turkish Student Association, said her friends “have lost family members and are mourning, but they’re still out here making an effort to raise money and have gathered resources to send back home.” (UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liashcheva)

‘It feels good to be useful’

Students in campus organizations whose families in Turkey and Syria are safe said they’re feeling the pain of classmates whose lives are forever changed by the quakes, and they want to help. Remarkably, their impacted friends are joining in.

“It is hard to balance personal life, emotional devastation and relief efforts. My friends have lost family members and are mourning,” said Meltem Su, president of the Turkish Student Association, which is raising funds for nonprofit organizations. Her family’s heritage is Turkish and Azerbaijani.

Sarp Kurtoglu, who came to Berkeley from Turkey three years ago to study bioengineering, also is advocating for more resources and for volunteers to help with rescue efforts in his role as president of the International Students Association.

“We know that there are so many more people who are under the rubble right now, waiting to be rescued,” he said, adding that while his own family wasn’t in the quake zone, waking up every day to a climbing death toll is “truly devastating.”

On Feb. 10, Berkeley’s Graduate Division contributed a community gathering for Turkish and Syrian students and those with connections to the region. And Doaa Dorgham, who leads the campus’s South Asian, Southwest Asian and North African Initiative (SSWANA), collaborated with Berkeley administrators to provide targeted outreach to students, staff and faculty connected to the quake zones and to suggest avenues to boost relief efforts.

Dorgham, who is Palestinian, said nearly 100 international students on campus are from Turkey and Syria, which are among the over 30 countries represented in the initiative. It aims to improve representation and resources for all of these student communities, she said, and to “uplift their stories.”

Compared to the Ukrainian crisis, Dorgham said some in the Berkeley community “are feeling like there hasn’t really been a lot of global attention given” to the emergency in Turkey and Syria and that this ‘leads to less organizing.”

But she said she’s encouraged by people from many corners of campus “coming together” to lend hearts and hands to uplift those in need. Added Turkish student Mehmet Donmez, “It feels good to be useful.”

Sarp Kurtoglu, who came to Berkeley from Turkey three years ago to study bioengineering, is president of the International Students Association. (UC Berkeley photo by Sofia Liashcheva)

Scholars lead reconnaissance team to investigate ‘rare event’

Currently, Selim Gunay and Khalid Mosalam’s structural reconnaissance team is operating virtually, using data from ground motion sensors to model the seismic shaking that occurred and analyzing photos of collapsed buildings to identify structural weaknesses. According to Gunay, their preliminary analysis suggests that the shaking was so extreme that it exceeded the design limits of many of the buildings in the region, despite Turkey’s strict seismic codes.

“This was quite a rare event,” Gunay said. “It’s also important to highlight that the presence of two very big earthquakes back-to-back also had a major effect on these structures and contributed to their collapse.”

While the scale of the destruction is overwhelming, the team has found glimmers of hope. Their observations suggest that a technology called seismic base isolation protected many hospitals from the impacts of the extreme shaking. It also appears that many of bridges in the region remain intact.

As the investigation continues, Gunay may travel to Turkey to collect additional data via field visits and portable sensors. Gunay’s family members, who are mostly based in Turkey’s capital city of Ankara, are safe at this time. However, despite being located more than 250 miles from the epicenter, they felt shaking from the second quake.

“There is so much we can learn from such an event,” Mosalam said. “But at the same time, it’s not a lab experiment. It’s an event that touches a lot of people — people have lost their lives, people are being relocated. So, learning from these events, as important as it may be, has to be handled very carefully. Otherwise, you could get in the way of rescue and recovery.”