A history of innovation: Berkeley entrepreneurs, companies that changed the way we live

Graphic by Neil Freese

September 29, 2023

This is the first story in a Berkeley News series highlighting UC Berkeley innovators, researchers and entrepreneurs from throughout history who have improved the way we live. Share your nominations by emailing us at [email protected].

Visit the Entrepreneurship at Berkeley site for more information about how the Berkeley community is creating innovative and equitable solutions to society’s greatest challenges.

The culture and spirit of innovation at UC Berkeley throughout history can be seen in the changemakers — the Berkeley students, researchers, entrepreneurs, faculty members and alumni — who have helped in countless ways to improve our lives and our world.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

Well-known innovators from Berkeley include Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna, whose development of CRISPR is arguably the world’s most important scientific advancement in decades, and alumnus Steve Wozniak, who co-founded Apple and revolutionized the home computer. The intellectual fingerprints of Berkeley founders and researchers can also be found on companies and inventions that run the gamut from OpenAI and ChatGPT to PCR Covid-19 tests, the polygraph and even the computer mouse.

Members of Berkeley’s community of innovators have discovered and created thousands of inventions. Today, in the U.S. and abroad, over 2,000 patents issued for those Berkeley inventions are still active. And nearly 300 startup companies and 800 products commercialized have come through Berkeley patent licenses, according to Berkeley’s Office of Intellectual Property and Industry Research Alliances.

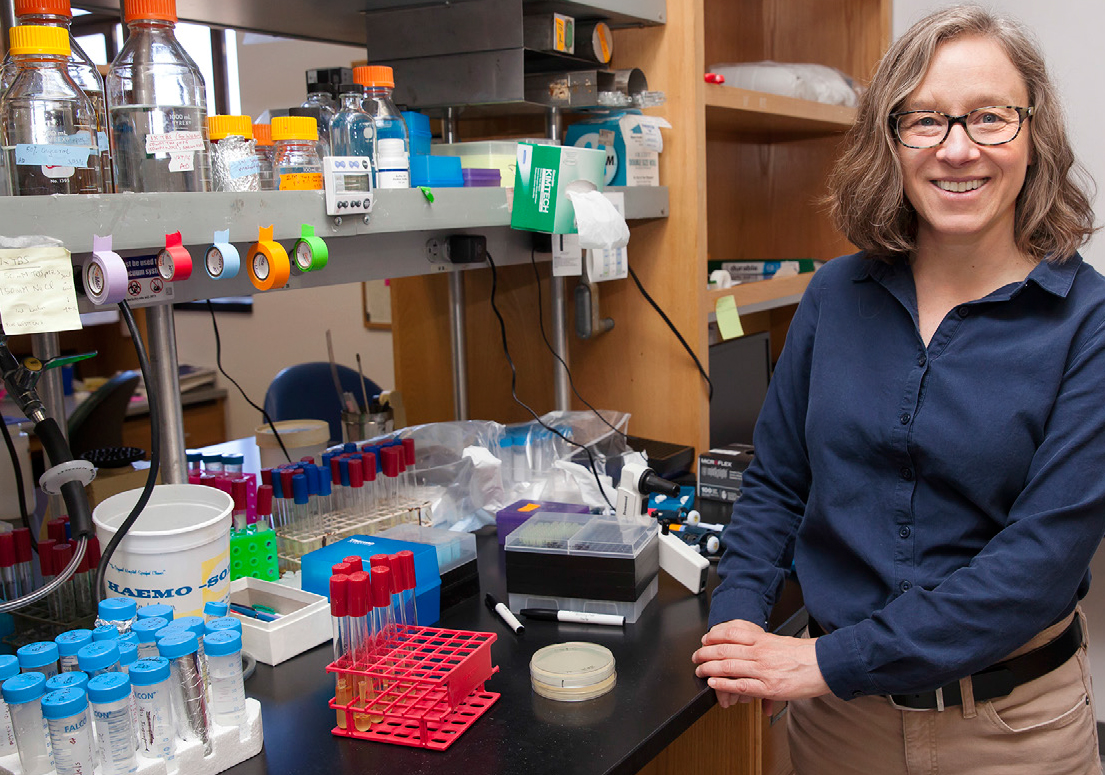

Berkeley students, alumni and faculty are continuing to develop innovative research and founding companies like never before, said Berkeley’s Chief Innovation and Entrepreneurship Officer Rich Lyons. An example is Kathleen Collins, a Berkeley biology professor who recently founded Addition Therapeutics, a breakthrough gene therapy company with technology for safe gene insertion into the genome.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

Berkeley’s newest entrepreneurs run the gamut, from researchers who have launched startups with their innovative discoveries, to students who have ideas for potentially changemaking companies.

Through Berkeley Changemaker courses, students across many disciplines, and from different backgrounds, are introduced to entrepreneurial thinking. And with over 20 startup incubators on campus, they have constant access to mentorship from Berkeley faculty and alumni to launch their startups and laboratories to conduct research.

Berkeley faculty are also creating spaces for students that have historically lacked the access to promote their potentially world-changing research.

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

For example, Bioengineering professor Aaron Streets was recently honored with Berkeley’s 2023 Chancellor’s Award for Advancing Institutional Equity and Excellence for being a tireless advocate for increasing diversity in STEM research. Through his Next Generation Faculty Symposium, Streets has given postdoctoral candidates, and potential entrepreneurs, from underrepresented communities an opportunity to showcase their work to the masses.

And these cumulative efforts across campus to expand the depth of Berkeley’s research and startup culture have paid off.

Recently, for the sixth straight year, Berkeley was recognized by PitchBook, a research firm that collects and analyzes data for the venture capital and private equity industries, as the best public university in the world for the number of startup founders it has produced. Berkeley also took the No. 1 spot for the number of companies that its undergraduate students and alumni have founded.

For Lyons, this is further evidence of Berkeley’s leadership in innovation.

“If we’re talking about a more entrepreneurial and innovative way of contributing to society, then a university that has, in its very DNA, a mindset of questioning the status quo, is a profoundly valuable asset,” said Lyons. “At Berkeley, we have doubled down on it, and that has continued to attract real innovators that live with agency and understand the traction their lives can have on the world.”

Here are just some of the entrepreneurs and companies with Berkeley roots that have uniquely innovated and continue to do so for the greater good.

Radically transforming electronic chip design

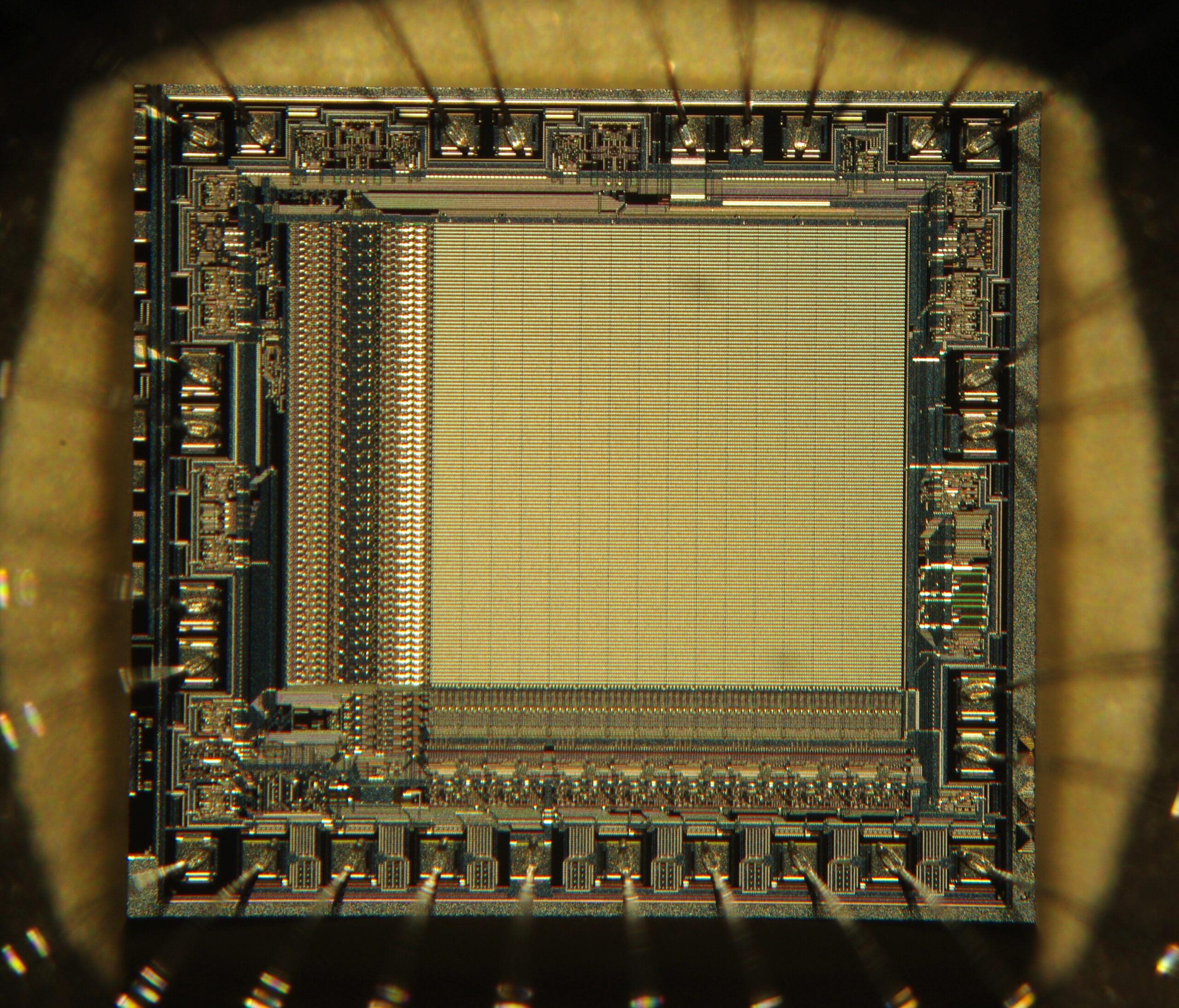

Wikimedia Commons

Semiconductors are an essential component of our daily lives. Simply put, they control and manage the electrical currents in electronic devices, allowing them to function efficiently.

So whether it’s your smartphone, laptop, calculator or car, it’s highly likely that its design was influenced by Berkeley Professor Alberto Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, an electrical engineer and computer scientist regarded by many as a pioneer in electronic design automation: a market segment that has transformed the way electronic chips and computers are built.

In the past 50 years, Sangiovanni-Vincentelli, currently Berkeley’s Edgar L. and Harold H. Buttner Chair of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, has published over 1,100 papers and nearly 20 books about his research and given numerous awards and honorary degrees for his contributions to science.

When Sangiovanni-Vincentelli first stepped foot on campus in 1975, he was a young engineer from Milan, Italy, who was researching network theory and how to solve circuit problems. Just a few years later, at age 28, he became an assistant professor in Berkeley’s electrical engineering and computer science department. As a faculty member, he conducted research in an area that he wasn’t familiar with: nonlinear nondifferentiable optimization algorithms for circuit design.

Berkeley provided him with the tools, resources and colleagues to develop his ideas. Sangiovanni-Vincentelli and his colleagues raised industry funds to build an entire floor in Cory Hall to host faculty and students working on tools and algorithms for semiconductor design.

Courtesy of Alberto Sangiovanni-Vincentelli

This enabled him to launch the processes needed for him to revolutionize electronic chip design that included the creation of simulation tools that speed up electronic circuit design and fabrication, the automation of circuit design with hardware programming languages, and algorithms to geometrically optimize circuit placement for performance and energy efficiency.

This work led him in the late 1980s to found Cadence and Synopsys, two companies that streamlined design processes in the semiconductor industry. To this day, they lead the electronic design automation market and provide technology to industry leaders like Apple, Intel, Tesla and Boeing.

Courtesy of Alberto Sangiovanni-Vincentelli

Sangiovanni-Vincentelli’s electronic innovations have enabled advances in communications, computing, health care, military systems, transportation, clean energy and countless other electronic applications.

Last spring, Sangiovanni-Vincentelli won the BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Information and Communication Technologies, a global award that recognizes world-class research. He received $427,000 and was cited for radically transforming the design of the chips that power today’s electronic devices, giving rise to the modern semiconductor industry.

But despite such accolades, Sangioanni-Vincentelli said the relationships he has created over the years are the most important to him. He gives back to Berkeley’s entrepreneurial community as an adviser for Berkeley SkyDeck, the campus’s premier startup accelerator. SkyDeck Executive Director Caroline Winnett said Sangiovanni-Vincentelli is an extraordinary resource and gives invaluable advice and guidance to up-and-coming Berkeley startups and founders.

“He always receives rave reviews from our founders,” said Winnett, one of which jokingly lives by the saying, “A Vicentelli a day keeps failure away.”

Courtesy of Alberto Sangiovanni-Vincentelli

“I always tell people, don’t force it,” said Sangiovanni-Vincentelli. “If you like to teach and do research, let that be it. If you’d like to work for a big company and in a big research lab, that’s perfectly fine, too. And if you aspire to create a new company, do not hesitate and do it.

“Do not feel pressured to follow a career path that may make you unhappy. It is your one and only life, and it is important you are happy in whatever you do.”

And the founder of Tesla is?

We all know Elon Musk.

The SpaceX founder and owner of the social media platform formerly known as Twitter has become one of the most well-known entrepreneurs in the world. And as the CEO of Tesla Inc., Musk has undoubtedly changed the way the public views the accessibility of solar energy.

And Tesla has grown into an industry magnate, eclipsing over $80 billion in revenue. But what many people don’t know is that the founder of Tesla was not Musk.

The company, Tesla Motors, was originally founded in 2003 by Marc Tarpenning, a Berkeley alumnus, and his co-founder Martin Eberhard. Tarpenning, a Sacramento-native, served as Tesla’s vice president of electrical engineering, and Eberhard its CEO. The company, in its early years, was solely focused on the production of electric cars as a solution to the overconsumption of oil.

“People have asked me why I would want to start a company,” Tarpenning said during a Berkeley Innovators lecture co-sponsored by The Foundry@CITRIS. “And the answer is because there are things worth changing.”

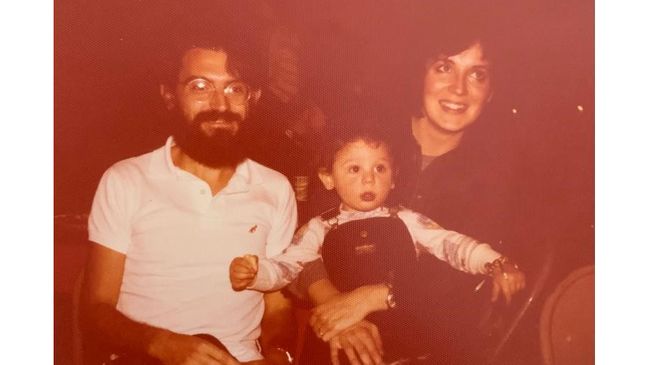

Courtesy of Berkeley College of Engineering

As a student at Berkeley in the early 1980s, Tarpenning said he enjoyed the instructional depth of his courses and the opportunity to learn things in a rigorous way. When it came to independent research and projects on campus, he told Berkeley SkyDeck that “anything unusual that you wanted to do, you could actually probably do it at Berkeley,” and he even recalled bringing his own homemade computer to use as a student on campus.

After graduating from Berkeley in 1985 with a bachelor’s degree in computer science, Tarpenning traveled around the world, working with several companies as an engineer. Upon moving back to the Bay Area, he met Eberhard, who was at the time the boss of Tarpenning’s old college roommate.

The duo in 1997 founded a startup, NuvoMedia, an e-book venture. When it was acquired by Gemstar-TV Guide, Tarpenning and Eberhard began to delve into finding solutions to reducing the consumption of oil. Through their research, they found that oil is used predominantly for transportation. And customers who bought and leased electric vehicles prior to 2002 were some of the richest customers in the industry.

“Our conclusion was that customers were not buying these cars to save money. These people weren’t concerned with how much money they were spending on gas,” Tarpenning said in a campus interview. “Every driveway in Palo Alto had the Porsche and the Prius, and the owners spent more on lattes than they did on gasoline.”

Joachim Kohler Bremen via Wikimedia Commons

With innovations in lithium-ion batteries becoming more prevalent at the time, Tarpenning looked for a way to build an electric car that could go up against the best sports cars in the industry. In spring 2003, Tesla Motors was incorporated, and a year later, the company began raising venture capital supported by Musk, who took a majority stake.

After several years with rounds of funding and vehicle prototypes Tesla announced its first car, the Roadster, and it was later followed by the Model S, which became one of the most sought-after and highly reviewed electric cars.

In 2007, Eberhard left the company after a falling out with Musk. Tarpenning followed in 2008, eventually leaving Musk as Teslas CEO. The company is currently valued at over $100 billion and continues to manufacture electric vehicles, stationary battery energy storage devices, solar panels and shingles, and other related solar and electric products.

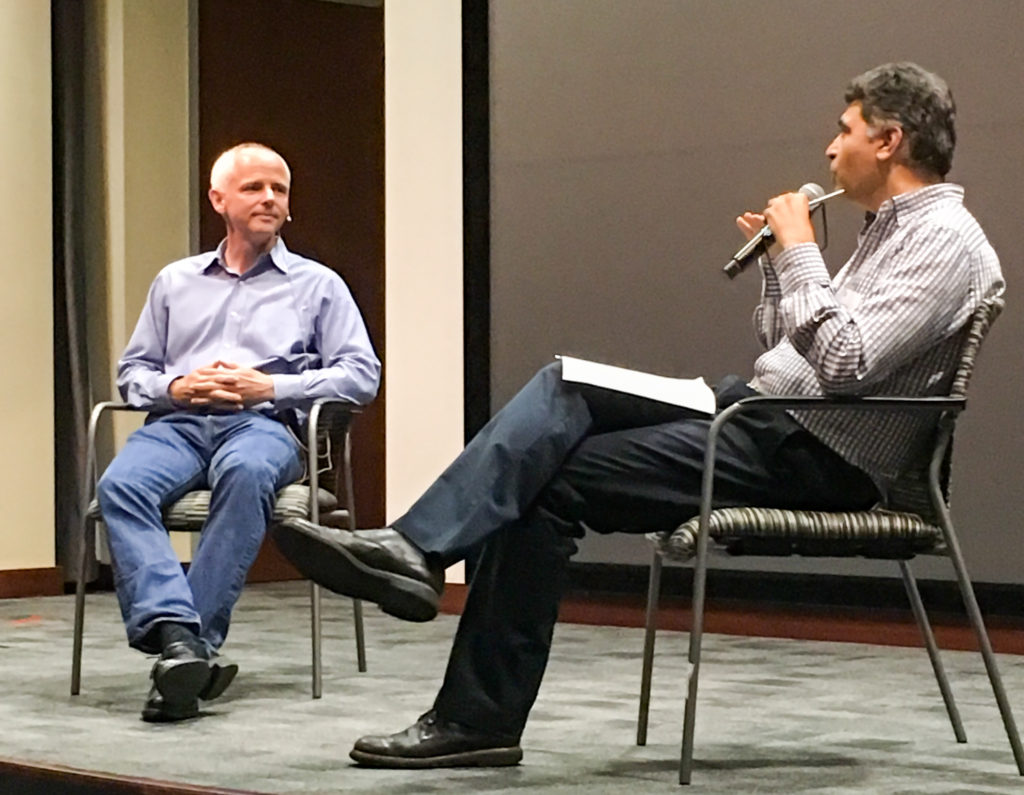

Courtesy of UC Berkeley SkyDeck

Tarpenning, who remains a Tesla shareholder, has since served as an adviser for several companies and boards, including Berkeley SkyDeck. He also is an investor in Spero Ventures, a venture capital firm in Redwood City dedicated to companies that help progress society into “a future we all want to live in,” he said in a Berkeley SkyDeck interview.

“We want to reach a point in the future where we have sustainable abundance. [So] we look for companies that will have that kind of impact. Those will be the big companies of the future.”

We’ve got the whole world in our hands

Seeing the world through a different lens is John Hanke’s gift to us.

Courtesy of Niantics Lab

The Berkeley alumnus, in 2005, led the creation of Google Earth, the world’s most widely used geographic information system (GIS) service. It gives anyone with an internet connection access to 3D views of the world around us via satellite imagery and streetscape photography.

Google Earth, Maps and Street View are used by over 1 billion people every month.

Hanke’s time at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business helped to support his entrepreneurial endeavors. In an interview with Berkeley Haas, Hanke said that a guest speaker at the school, Silicon Graphics founder Jim Clark, gave him the courage to go out and pursue his own goals.

“After Clark spoke,” Hanke said, “eight or nine of us had dinner with him, and it was the most amazing thing, to connect what you imagine out there in the world and make it real and tractable.”

Hanke came to Berkeley in the mid-1990s to join the Haas MBA program and immediately co-founded a company that developed one of the first online games that allows hundreds of users to play together in a virtual environment.

Jerry Engel, who is faculty director of Berkeley’s Venture Capital Executive Program, was Hanke’s entrepreneurship teacher and mentor during his time at Berkeley and said Hanke was a “quiet leader” with a “deep strategic mind.”

Courtesy of Berkeley Haas

“One could say that, in fact, it was the attributes of Haas students and alumni like John from which the Haas business school guiding principles evolved,” Engel said.

In 2001, five years after graduating from Berkeley, Hanke co-founded Keyhole, a geospatial data visualization firm that ended up developing an earth browser. The company got media attention for its ability to provide digital images of the war in Iraq.

That led to Google acquiring Keyhole in 2004 for $35 million. Hanke worked as Google’s VP of product management for the Geo division and pushed several map-connected projects forward, including for Google Earth, Maps and Street View, in which images are collected using a six-lens camera capable of snapping 360-degree photos.

In 2010, Hanke launched Niantic Labs through Google, an augmented reality gaming unit that eventually led Hanke to create other products including Pokemon Go, which at its peak attracted nearly 30 million users a day.

“I saw an opportunity to use technology to help people get out into the real world,” Hanke said in a Berkeley Haas interview.

And in so many ways, he has, said Engel.

“I have seen John grow from student, to leader, to teacher,” said Engel. “It has been great to know and work with John over these almost two decades. I certainly have learned as much and perhaps more from him, than he has from me.”

A Bio-Rad Berkeley couple

Courtesy of Bio-Rad Laboratories

From the pioneering of professor Doudna’s CRISPR technology to the creation of PCR testing through Berkeley-affiliated companies like CETUS, Berkeley has a long history of producing biotech research and startups.

And in recent years, the campus has grown its biotech community, including through opening the Bakar BioEnginuity Hub a renovated state-of-the-art building that houses the next world-changing startups and the campus’s Life Sciences Entrepreneurship Center.

Courtesy of Darren Cooke

“The abundance of biotech research that has come out of our campus over the years is phenomenal,” said Darren Cooke, executive director of Berkeley’s Life Sciences Entrepreneurship Center. “And that work often turns into companies with serious longevity.”

An example of such a company, said Cooke, is one of Berkeley’s first biotech startups, Bio-Rad Laboratories, a developer and manufacturer that specializes in technological products for the life sciences and clinical diagnostics markets.

For over 70 years, it has produced life sciences products instruments, software, consumables, reagents that support research in the areas of cell biology, gene expression, protein purification and quantitation, drug discovery and manufacture, food safety and science education.

Bio-Rad products and systems provide clinical information for blood transfusions, diabetes monitoring, and autoimmune and infectious disease testing. These products have helped to advance the discovery process in research labs around the world and support the diagnosis, monitoring and treatment of diseases and other medical conditions.

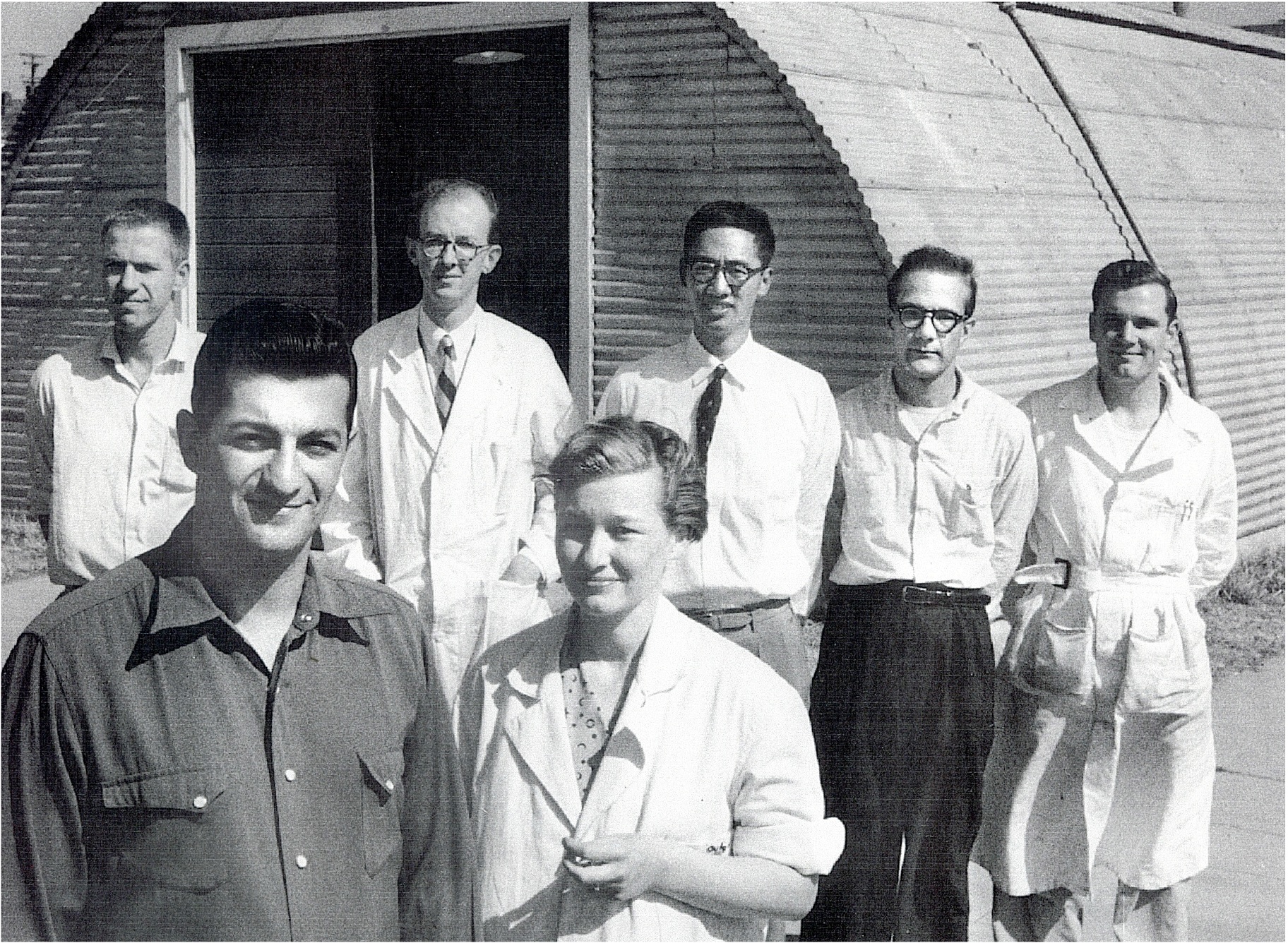

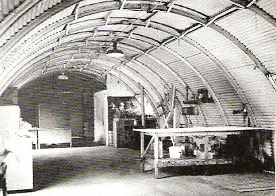

Courtesy of Bio-Rad Laboratories

The company was founded by two Berkeley alumni, Alice and Dave Schwartz, who both got degrees in biochemistry and chemistry and then, in 1952, got married and founded Bio-Rad.

They opened the laboratories in a Quonset hut in Berkeley with just $720 in savings. The name Bio-Rad comes from the words biochemicals and radiochemicals, the company’s first offerings.

In 1960, the company’s presence in biological discovery and health care research expanded, and it had 11 employees and $150,000 in sales. By 1966, Bio-Rad reached $1 million in total sales and became a publicly-traded company.

Now headquartered in Hercules, Bio-Rad has 8,200 employees and $2.8 billion in annual sales of life sciences research tools and clinical diagnostics.

David Schwartz died in 2012, and Alice Schwartz has since stepped down after serving on the Bio-Rad board for over 70 years. Forbes ranked her among the richest people in America, with a net worth estimated at $2.5 billion.

The couples son, Norman Schwartz, is currently the CEO and president.

“Bio-Rad continues to revolutionize research in the life sciences, evolving and changing with the times,” said Cooke. “It provides products that change the world. And for current and future Berkeley entrepreneurs, Bio-Rads journey is a reminder that we are part of a long history of startup successes.”