Why are there so many people from the Philippines in Hawaii? Colonialism.

Courtesy of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology

October 9, 2023

As the world witnessed the tragic Maui fires in Lahaina this past summer, it was evident amid the devastation of burned homes, businesses and sacred Hawaiian spaces — along with the missing and the dead — that many of those impacted by the wildfire were from working class Filipinx and Filipinx American families.

Prior to the fire, nearly half of Lahaina residents traced their roots back to the Philippines. And according to the U.S. Census Bureau, statewide, a quarter of Hawaii’s 1.4 million are Filipinx and/or Filipinx American — the largest percentage of Filipinx residents in any state in the country.

Which begs the question: Why are there so many Filipinx families in Hawaii?

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

The answer can be found by delving into our nation’s history of “long colonialism” in the Asia and the Pacific region, said UC Berkeley Ethnic Studies Professor Vernadette Vicuña Gonzalez.

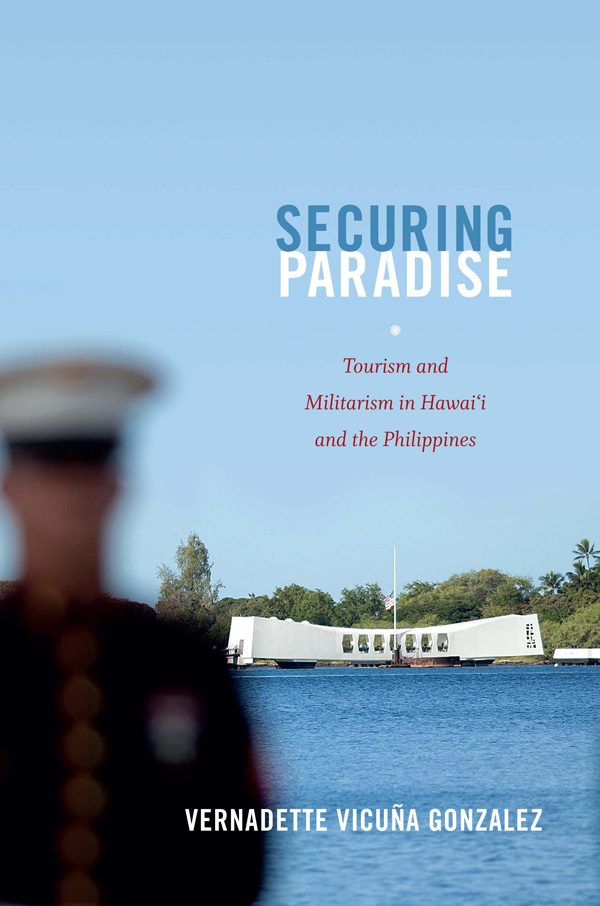

“The Lahaina fire is a particular flashpoint of the history of long colonialism in Hawaii. … It’s part of the story of militarism and labor extraction and exploitation of U.S. imperial nodes,” said Gonzalez, author of the book Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines. “Filipinx residents have played a role in that history, being used as cheap, exportable labor. And despite being exploited, many of them settled in Hawaii and started families that are still there to this day.”

Gonzalez was born and raised in the Visayas island group in the Philippines and immigrated to upstate New York in the 1980s when she was 11. As an English major at Princeton University, Gonzalez fell under the tutelage of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Toni Morrison, then went on to earn a Ph.D. in ethnic studies at Berkeley.

This summer, Gonzalez moved back to the Bay Area after nearly 20 years as a faculty member in the University of Hawaii at Mānoa’s American Studies department. Next semester, she will teach courses at Berkeley that delve into the cultures of U.S. imperialism and diaspora, and Asian American cultural politics.

Berkeley News recently spoke with Gonzalez about the impact of U.S. colonialism and capitalism on Filipinx people in Hawaii, how Filipinx residents have found commonalities and belonging in Hawaii, and why it is important for Filipinx students and researchers to share their stories about what it means to be Filipinx and/or Filipinx American.

Berkeley News: What are the historical reasons behind why there are over 340,000 people of Philippine descent living in Hawaii?

Wikimedia Commons

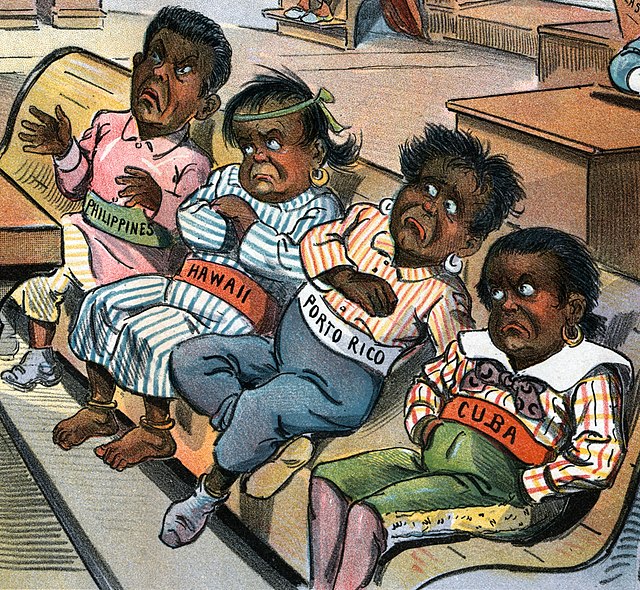

Vernadette Gonzalez: It has a lot to do with colonial history and the role that labor extraction plays in American capitalism. In the 1900s, before Hawaii became a state, the traffic in Philippine labor essentially brought Filipinx workers to Hawaii, and a lot of that had to do with the sugar plantation economy.

Those American corporations sought low-cost laborers, and they recruited, some would say extracted, from the Philippines hundreds of thousands of Filipinx men called “sakadas” to work the fields. They were paid sometimes as little as 90 cents a day, much less than other migrant workers from Japan and Korea.

Filipinx workers helped fuel Hawaii’s economy because of that cheap labor, and despite this exploitation, many of them settled in Hawaii and started families that are still there.

We also see a continued extraction of Filipinx labor today, with many Filipinx nurses and military servicemen and women migrating to Hawaii as part of the U.S. military’s hold on Asia and the Pacific.

Given that history, Do you feel like Filipinx people in Hawaii tend to stay in those industries of service and hard labor?

Yes, a large percentage of Filipinx residents in Hawaii continue to be domestic workers in hotels, resorts and restaurants.

I think that there is a way in which those industries pull in folks whose skills may not translate upon arrival in the U.S. So this is why you see folks in sort of what they call low-skilled jobs. But these jobs require lots of skill. They’re just not jobs you have to get degrees for.

UC Berkeley Bancroft Library

That’s why you’re seeing a lot more first-generation Filipinx migrants coming in as servers, as entertainers, folks doing the cleaning or the garden work. By the time you get to folks who are in their second or third generation, they may have gone to college or have had some college. So they’re aspiring to a different part of the occupational ladder.

And although in the past we have seen a Filipinx governor in Hawaii, and other prominent Filipinx figures, the number of Filipinx in higher education and government is disproportionately low in comparison to the total population of the state.

Many of the victims that were impacted by the recent fire in Maui were Filipinx families working in the tourism industry. Approximately 40% of Lahaina residents are Filipinx. How does the history of U.S. and corporate interest in Hawaii play a part in this tragedy?

The Lahaina fire is a particular flashpoint of the long colonial history in Hawaii that is reflected in other parts of the world, as well. It’s part of the story of labor extraction and exploitation and circulation in U.S. imperial nodes.

The way capitalism and U.S. migration works has always been a racist structure, where the workers are exploited and oppressed. So when you have a crisis moment, like this fire, there are going to be working class Native Hawaiian families and Filipinx families that are more intensely affected, in terms of the gradations of suffering.

Wikimedia Commons

And we are still seeing a lack of resources being afforded to these communities after the fire. You’re seeing Pacific Islanders, Filipinx and Hawaiians that have literally lost their homes but are being blamed for the fire. And these are the folks who have continued to battle state institutions and corporations over water rights for decades.

They are on the front lines of the bigger story of climate change.

And so this fire is one of those moments where you see the legacies of long colonialism and capitalism play out in a very spectacular way, along familiar socioeconomic and racial lines. This story has already been happening for centuries in terms of the war over water, monocrop farming and the impact of tourism on limited water sources all over Hawaii.

The reasons why there was fuel for the fire to happen was already an issue being fought by Native Hawaiians who are against mono-cropping, which then makes room for invasive species and rampant development that caters to everyone else but local residents.

So all those things that contributed to the fire were already happening. It is just now more visible to the greater public. And Filipinx families are suffering because of this.

In your research, you’ve described the similarities between the history of U.S. militarism and colonialism in Hawaii and the Philippines. How are these places in the Pacific still impacted by that history?

Hawaii is the headquarters to the U.S. military’s Pacific Command. The U.S. basically oversees that hemisphere by having access to those islands. And the Philippines itself was the former host to some pretty massive U.S. military institutions and reservations. Many of those sites have turned into tourist attractions from Pearl Harbor on Oahu, to the Malinta Tunnel on the island of Corregidor in the Philippines.

In my book, Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawai’i and the Philippines, I write about how these former military territories get re-territorialized when the military leaves. But there’s a flexibility in their use because the U.S. military movement is not always just about leaving.

It’s about coming back.

U.S. Navy

As Gen. MacArthur famously said about the Philippines during World War II, “I shall return.” So there is this constant interdependence and dance amongst the different territories in the Pacific. For example, the U.S. may be demilitarized in Okinawa, Japan. But those troops then move into Guam.

It’s like a shell game.

So that history continues to impact global relations for Filipinx people and those who are living in and/or are from those different sites throughout the Pacific. And in many ways, it has brought them together for a common cause: Demilitarization.

We have demilitarization movements that are supported by Filipinx and Native Hawaiians together in Hawaii that really show a clear sense of the commonalities and struggles that continue to impact people from these different places.

Oftentimes, that shared history would have these different groups competing for the same resources. But there continues to be a really vibrant demilitarization movement, particularly driven by women, in the Pacific because there is an understanding that militarization is a structure that shapes all of these places.

With that linked history and relationship to the U.S. empire, are there similarities between Filipinx and Hawaiian cultures in Hawaii?

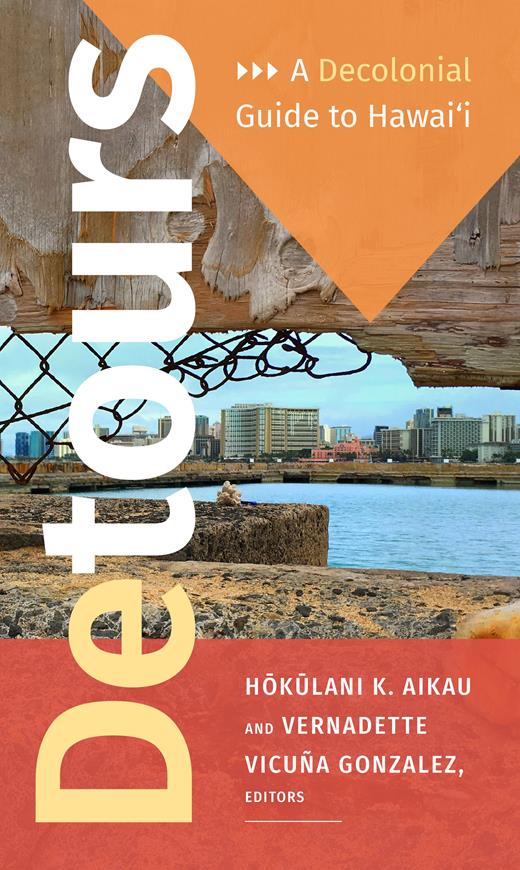

There are similarities when it comes to island cultures, in general, from food to music and art and so forth. But on the ground, there is also a common commitment to efforts around decolonization.

The book that I co-edited with my good friend Hokulani K. Aikau, Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawai’i, curates narratives about Hawaii, from Native Hawaiians, that go beyond the postcard perspectives of the island. It’s really about the different people who have come to call Hawaii their home.

And some of those stories are from Filipinx authors and artists that share a story that is still connected to Philippine history. A lot of the stories they tell are about what it means to be Filipinx in Hawaii and what a commitment to decolonization in Hawaii means for them as people of Filipinx descent.

Can you give an example of ways Filipinx artists have shared that story in Hawaii?

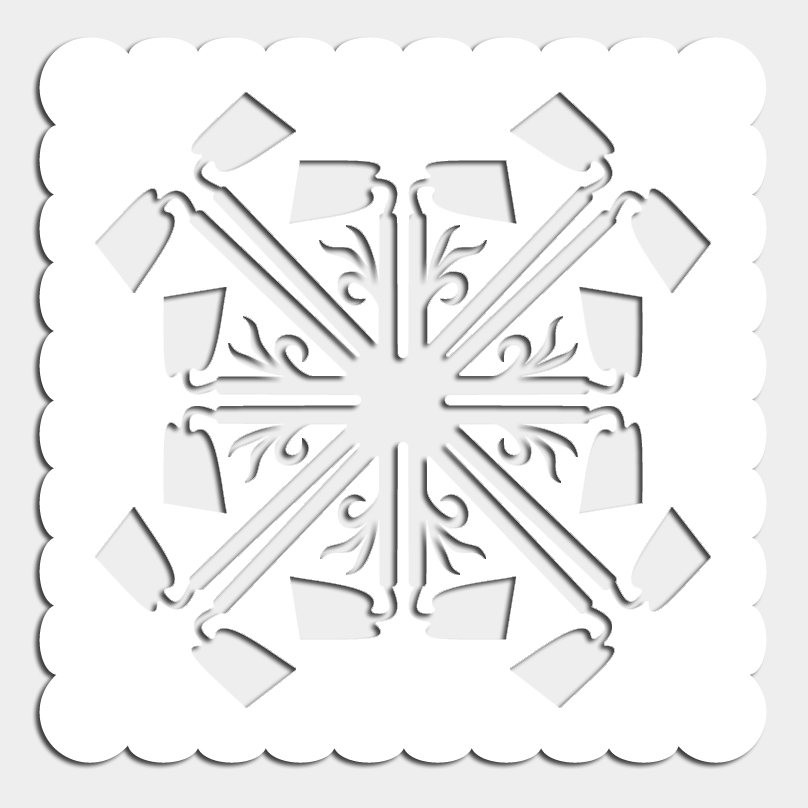

There is an amazing artist, Trisha Lagaso Goldberg, who creates plexiglass Hawaiian quilts to represent the stories of Hawaii that include Filipinx history.

A Hawaiian quilt is itself an interesting art piece that pulls together native traditions that include making the cloth out of bark. But it is also influenced by the sewing from the New England textile industry that was brought in by East Coast missionaries to Hawaii during the 1800s. Sewing schools were instituted during the U.S. colonial era to supply a lot of the delicate sewing work of things like lingerie for the U.S. market.

There are all these converging colonial histories that get unpacked when you look at something like a quilt. Hawaiian quilts usually consist of silhouettes of natural forms that represent the islands, like bread, fruit or flowers.

Photo by Trisha Lagaso Goldberg

Trisha takes that idea and makes it into plexiglass form that produces images of pick axes and hoes, which were the farm implements used by Filipinx workers on the sugar plantations. So she’s sewing and suturing those histories into something that is identifiable as Hawaiian, but also represents Filipinx history on the island.

It’s that type of art and relational way of thinking that promotes the points of connection that we have.

But what’s ironic is a few years back, during my research around traditional Hawaiian quilts, I found out one of the biggest places that they are now made in is a former military site in the Philippines — Clark Air Force Base. So like Hawaii, there’s also a really strong sewing culture in the Philippines because of American colonialism.

And now you see new circuits of cultural labor connecting these sites in the contemporary moment.

When you talk about these military bases and traditional artifacts being used and consumed as forms of tourism, similarly, in both Hawaii and the Philippines, does that impact how those people are seen by tourists, as well? Do you think tourists that travel to Hawaii can distinguish between Filipinx, Hawaiian or other Polynesian people and their cultures?

It is very easy for tourists to lump together all brown people, including Filipinx residents, in Hawaii. It’s part of the way Hawaii is marketed as this multiracial paradise. And in some ways, it is true that there are more mixed-race people in Hawaii than other states, or countries, even.

Wikimedia Commons

So many of my students in Hawaii are mixed race, and for them, they sometimes don’t know all of the ethnicities that they are, but they know there is a difference between all of the cultures they encompass. Being mixed race is common, so those conversations and questions of “Where are you from?” aren’t had as much.

In the continental U.S., the term Asian American is used quite often to describe Americans from Asian descent, but that isn’t something in Hawaii that has really taken off because of the specificity of Hawaii’s history. Folks don’t talk about being Asian American, they’re more likely to say they’re Japanese, or they’re Filipinx, or they’re Korean.

They are more likely to identify ethnically, or as that catch-all term “local,” versus this Asian American political, cultural and social category. So internally, it’s not so much a question of how Filipinx people identify themselves. Everyone knows about the nuances and different cultures.

Courtesy of dolanh/Flickr

But externally, people who visit Hawaii project their desires on local populations that they often objectify to fit their own version of what Hawaii represents to them.

They are likely to encounter Filipinx workers in their hotels doing all the service work, or in restaurants doing the cooking and cleaning. And so between that and who’s dancing at the luau, sometimes they’re Hawaiian, sometimes they’re Filipinx and sometimes they’re both.

But for tourists, that often doesn’t matter.

They are able to substitute one brown body for another so that their Hawaiian fantasy holds. And the nuances of Filipinx culture and community are lost.

What can be done to bring attention to the nuance of experiences in the Filipinx/Filipinx American community?

Storytelling is really important.

And we need to be a central part of telling our stories and to tell the diverse and hidden narratives of our communities. If we can do that, then we can imagine solutions that meet the moment and complexities of our communities.

The research is also valuable because it sheds light on the ways people have, both in the past and in the present, worked to move the project of decolonization and of justice forward. We need to ensure that the kinds of stories we have in the archive are not limited, otherwise our communities will be limited.

Wikimedia Commons

As a new faculty member, do you hope to have that kind of influence, to inspire Filipinx students at Berkeley to tell their unique stories?

I hope so. I’m teaching a Filipinx American class in the spring about cultures of U.S. imperialism and diaspora and also a class on Asian American cultural politics. We’ll be looking at culture defined very broadly, from food to fashion to literature to film, and how those forms tell the story of power and community presently, and in any given moment in history.

UC Berkeley Bancroft Library

I’m also having my students look at the archives of David Prescott Barrows to delve into how Filipinx people are existing in U.S. culture and who has had the power to shape these kinds of representations. We’ll also look at the Jessica Hagedorn papers, which are also at the Bancroft Library, to give an example of how Filipinx people can tell their stories under their own terms.

I want to give students a sense of the arc of moments that are really interesting when thinking about representations within the entanglement of the U.S.-Philippine empire. And to give them a sense that they are currently part of that conversation and that history.

That they can be the ones to shape the future narratives of history, where Filipinx communities are fully represented.