No longer forgotten: Berkeley researchers innovate to shine light on hidden histories

Their goal is to teach a new generation of students about individuals and groups left out of history books or misunderstood.

Courtesy of Department of Ethnic Studies

March 28, 2024

In UC Berkeley’s Social Sciences Building, the voice and likeness of Black slave poet George Moses Horton is being recreated with augmented reality. Meanwhile, the history of Latinx sexuality and gender is the subject of a podcast by ethnic studies students. And a new narrative nonfiction book for Gen Zers by a history professor and his daughter is retelling the story of the Black Panther Party.

As policies backed by U.S. legislators across the country seek to erase the histories of marginalized communities through the banning of books and the falsification of historical events, Berkeley faculty and researchers are pioneering innovative projects to bring those accounts — often hidden and misunderstood — into the limelight.

And they’re doing so to engage a new generation of Berkeley students, and in changemaking ways.

“Berkeley research that centers students and their diverse experiences aligns with our mission as a public-serving institution,” said Berkeley Vice Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion Dania Matos. “This is innovative scholarship that transforms campus for our students and transcends the greater public discourse as to what histories should be acknowledged and valued.”

Reclamation through augmentation

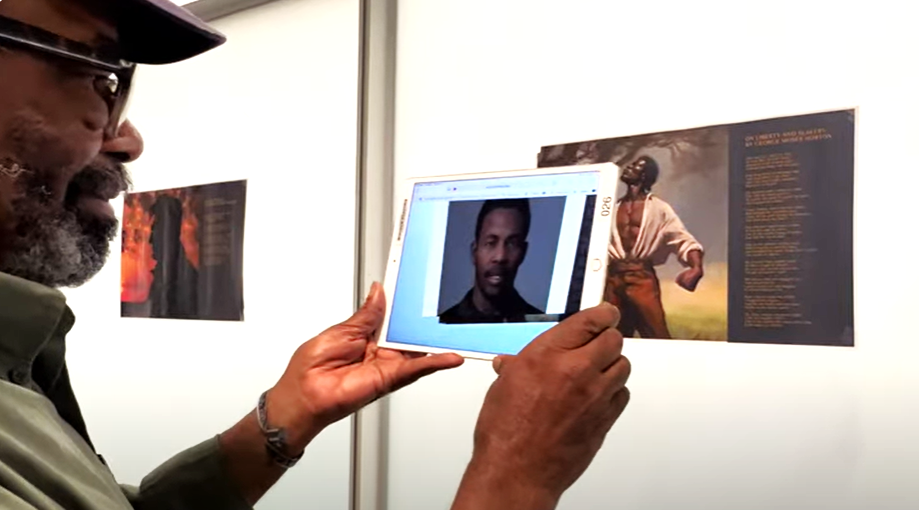

Courtesy of Cecil Brown

Hip-hop artists like Jay-Z and Too Short may have something else in common besides being rap music legends, said Berkeley alumnus Cecil Brown, a senior lecturer. They’re also lyricists indirectly impacted by a trailblazing Black writer, George Moses Horton, who was the first Black enslaved poet ever to be published.

Brown is now using artificial intelligence (AI) and augmented reality (AR) to painstakingly bring Horton, born into slavery in 1798 in North Carolina, back to life so others can know him and his talent.

In 2022, while he was a lecturer at Stanford University, Brown began delving into AR and AI technologies to understand their instructional possibilities. An accomplished writer in his own right, Brown said he turned to using the technology to center Horton, whose brilliance had been lost in the annals of history.

“I wanted to transport people back to the Antebellum South, when Horton was alive, and to reclaim that era of Black history by retelling it in his own words,” said Brown.

Illustration by Midjourney

Aided by Southern author and playwright Caroline Lee Hentz, Horton’s poems were first published in local newspapers in the late 1820s, and later, he produced a book of poems, The Hope of Liberty, in 1829. Horton hoped in vain that book sales would buy his freedom; but he was eventually freed after the Civil War. He continued to write poetry about the mistreatment of Black people in America until his death sometime after 1867.

Brown first collected all of Horton’s poetry and archival images of him. To replicate Horton’s appearance and voice, Brown researched Horton’s bloodline and reached out to his living descendants to model an AI version of him, using the faces and voices of his living relatives.

Brown received funding for the project through a grant from Professor Cecil Giscombe, the Robert Hass Chair in English, and in collaboration with the UC Berkeley XR (Extended Reality) Community of Practice, which is sponsored by Berkeley’s chief technology officer. The campus group supports Berkeleyans interested in using XR technologies for research and instruction.

UC Berkeley/ Sofia Liashcheva

Chris Hoffman, operations director at the Forum for Collaborative Research at the Berkeley School of Public Health, worked with Brown to assemble a small team of Berkeley design students and staff who eventually crafted an immersive exhibit about Horton.

Using new media storytelling tools, users can scan their smartphone devices over QR codes that narrate American history in the time of Horton via audio recordings that are enhanced by images of historical archives, events and figures. Users also can ask Horton questions about his life and listen to him recite his poetry.

“We are reclaiming our stories through his words and this digital manifestation of Horton,” said Brown, “a man who should be remembered for his contributions to Black people and our history.”

For Brown, the project is also about giving Black students access to these innovative technologies and to inspire them to pursue work in the STEM fields, which lack Black representation.

Graduate student Maria-Teresa Carmier, who is majoring in design innovation, helped Brown with an on-campus exhibit of the project last fall. She also created an immersive interactive storytelling experience for the audience by integrating voice-cloning technology with Amazon Web Services (AWS) for dynamic character interactions.

UC Berkeley/ Sofia Liashcheva

While Carmier no longer works on the project, she said she hopes to see an iteration of Brown’s creation displayed in museums across the country, “especially where Black creativity thrives.”

“This project really gave folks a way to interact with history in new ways and learn how technology could support that effort,” Carmier said. “As a parent of two Black sons, at the event it was an especially proud mama moment to see my children learn about early Black creativity and find pride in being creatives themselves.”

History’s personal touch

For Berkeley faculty members Pablo Gonzalez and Harvey Dong, history can only be fully appreciated through a facilitation of visual and oral stories and experiences.

Their students, throughout the years, have benefitted from learning through that historical lens, producing engaging projects ranging from digital magazines that explore the hidden histories of Chinese American immigrants in California to in-depth podcasts that delve into vulnerable subjects, like Latino masculinity, to augmented reality tours that captured images of Black Lives Matter murals in Oakland before they were destroyed during the pandemic.

Courtesy of Pablo Gonzalez

Gonzalez, an ethnic studies lecturer, has schooled himself and his students since 2018 in the use of new and emerging digital tools to use for podcasts and AR. In 2020, after receiving a Berkeley Changemaker Curriculum Grant, he put those funds to use and created the Ethnic Studies Changemaker Scaffolding and Building Communities project, a student-led collaborative that uses podcasting and AR to amplify the voices and histories of marginalized communities.

The project also has been funded by a 2023 Berkeley Collegium Grant, given annually to campus projects that produce innovative research.

As part of the project, and in his Mexican and Central American history courses, Gonzalez asks students to record interviews with their parents about their families’ histories in the U.S. Students then digitize family photos, letters, texts and audio recordings and thread them together to create augmented reality packages that narrate the stories of their lives — oral histories to pass down to future generations.

Courtesy of Cecelia Lopez

As a student, Berkeley alumnus Cecilia Lopez worked on Gonzalez’s changemaker project with other students to produce the Digna Rabia journal, a 400-page digital zine that incorporates augmented reality, 3D images and audio recordings of student’s family histories, ethnographies and migration experiences.

Lopez, who works for a Southern California nonprofit, said those stories “puts things into perspective to contextualize the past, the present and the future.”

“Parents who see their stories in this format for the first time are so touched by the project that they cry,” said Gonzalez. “And with the erasure of our stories still being discussed in the halls where laws are made, there is no greater time to do this than now.”

As an Asian American studies lecturer, Dong also has a storied Berkeley history. He was an activist with the Third World Liberation Front in the 1960s. Like Gonzalez, Dong utilizes podcasts and AR digital journals and magazines to engage his students in history.

His students’ project topics are often unfamiliar, even to him, said Dong. They include the evolution of Chinese restaurants in America, the persecution of Chinese American scientists, and Chinese families’ hesitance to participate in environmental justice.

To supplement those projects, Dong will often recommend and connect his students to experts in those fields, including Asian American scholars and professors such as Michael Omi, Russell Jueng and Lok Siu.

Currently, students in Dong’s Chinese American history class are exploring the experiences of Chinese immigrants who lived in Locke, California, an area near the Sacramento Delta and a community often overlooked in Asian American history.

“Typical Asian American stories rely heavily on stereotypes. Asians have been placed heavily in the category of ‘the other,’” said Dong, “that we are perpetual foreigners, or that we are part of a destructive yellow peril. So I try to introduce my students to nuanced ways to view our stories and our history through contemporary tools. … It is how we make history come alive.”

Berkeley alumnus Jaide Lin took several of Dong’s courses as a student and said that when it comes to learning about history, “Harvey is one of the best people to teach at Berkeley.”

Lin, who currently works for a clean energy consulting company, said he was inspired to pursue community organizing after making a video project in Dong’s class about the stories of Asian American and Pacific Islander advocacy groups in the Bay Area.

“Learning those stories definitely helped me to understand the narrative trends and components of history,” said Lin. “Our past and what is to come aren’t just joint events spontaneously happening. They are all intertwined.”

A family affair

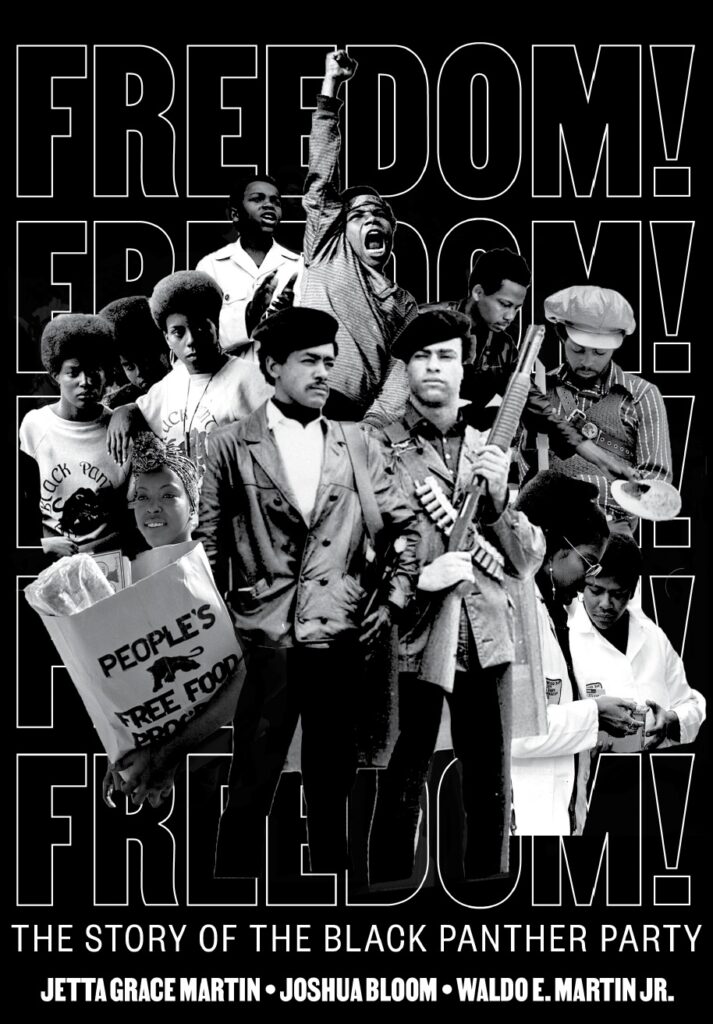

When publishers began contacting Waldo Martin about writing a young adult version of his 2013 book, Black Against Empire: The history and politics of the Black Panther Party, he said he wanted to make sure the nonfiction book had a captivating narrative that empowered youth to imagine a better world and to “not only complain about the injustices in society, but to do something about it.”

But Martin, a professor who has taught African American history courses at Berkeley for over 30 years, said he admittedly struggled about how to write an engaging story about the Black Panther Party for 12-to-18-year-old Gen Zers.

“I thought I was too old to be doing this, so I asked my daughter, Jetta [Martin], if she was interested,” he said. And that partnership led to Freedom! The story of the Black Panther Party, a comprehensive, youth-friendly narrative chapter book about the leaders of the Black Panther Party.

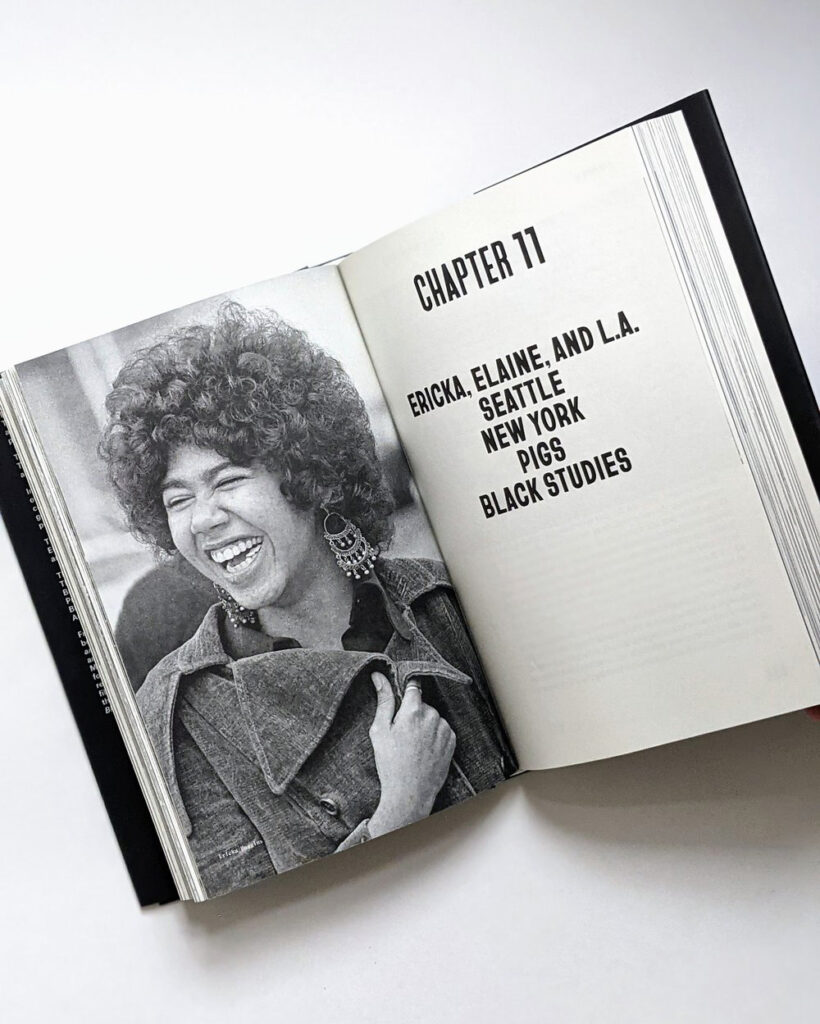

Jetta Martin, a Bay Area author, dancer, choreographer and real estate agent, said she remembers sitting at home, writing as a child on her father’s old typewriter. Decades later, writing a book with her father has been a dream come true, she said. She approached the writing of the story by asking herself questions like: What if there was social media back then? And if half of the party were women, why are there no pictures of them?

“Just reminding myself of the different ways we could tell their story was important because there is so much historical literature around the party that it can be easy to replicate those images and perspective,” she said.

Courtesy of Waldo Martin

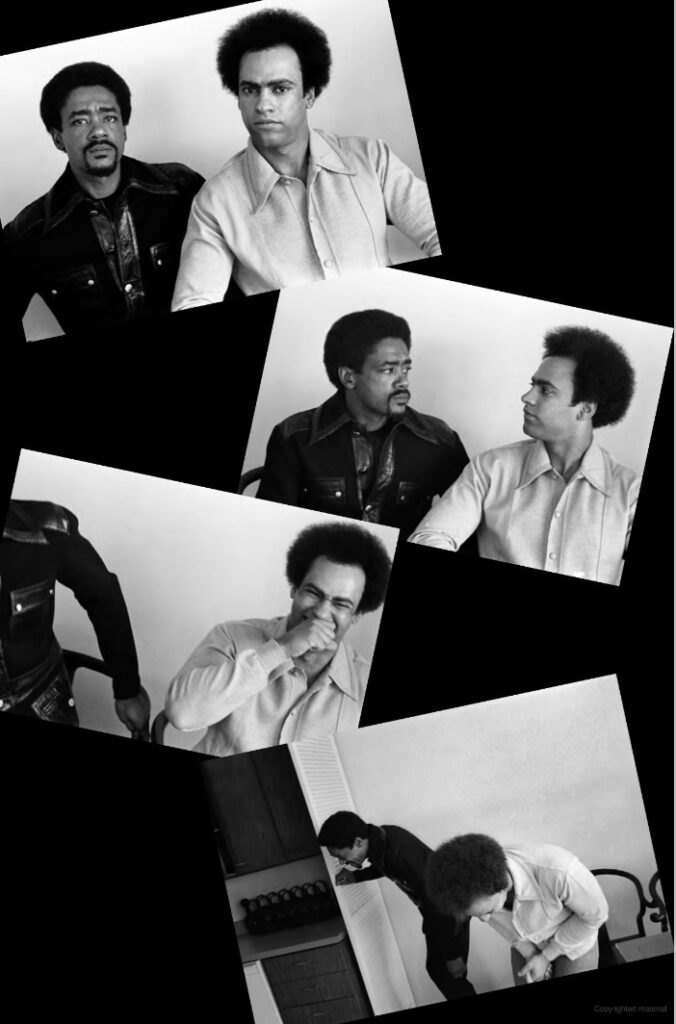

The book, also co-authored by Joshua Bloom, a former student of Waldo Martin, begins by telling the story of a group of friends, Huey and Bobby; Eldridge and Kathleen; and Elaine, Fred and Ericka. The young teens start a group to change their Oakland community, and they go through typical youth experiences, from playground fights over who gets to use the swings to cruising through the streets at night in Bobby’s car.

Somewhat poetic in cadence, the book tells the personal stories of each friend, male and female, who eventually led the Black Panther Party — from its rise through the 1960s and ‘70s to its eventual fall in the ’80s.

The book, which came out in paperback last month, has received rave reviews and won the inaugural Russell Freedman Award for Nonfiction and a Better World.

Waldo Martin said writing the over 300-page book, replete with stunning archival images and digital illustrations of party leaders, was “a labor of love” to complete with his daughter. He hopes it breaks the false assumptions that many people have about the Black Panther Party and humanizes its leaders.

Courtesy of Waldo Martin

“There is a lot of misinformation and ignorance about the party. To the general public, it is often viewed as if they were just a bunch of gun-toting Black thugs that hated white people,” Waldo Martin said. “But Jetta had a lot of insights that I didn’t have. She really made the story come alive in a way that told the story for what it truly was — a youth movement.”

Presenting this history to a new generation is “so gratifying,” Jetta Martin said, because there is a parallel between the experiences of the party and its members and present day events.

“The murder of Fred Hampton was the murder of George Floyd and was the murder of Breonna Taylor,” Jetta Martin said. “The echoes of history are connected in that way.”

“I hope a book like this can create that spark for young people to advocate for whatever it is that is their thing, because there is a certain alchemy of things that mixed together to create the Black Panther Party,” she said. “And I see that as inspiration, that maybe it can happen again.”