Berkeley Voices: Medieval song holds clues to lost dialects

March 5, 2024

Follow Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast about the people and research that make UC Berkeley the world-changing place that it is. Review us on Apple Podcasts.

Brandon Sánchez Mejia/UC Berkeley

In his research, UC Berkeley Ph.D. candidate Saagar Asnani looks at music manuscripts from between the 12th and 14th centuries in medieval France. He says only recently have scholars begun to use a wider variety of media and artistic expressions as a way to study language. “If we unpack the genre of music, we will find a very precise record of how language was spoken,” Saagar says.

To read medieval music, Saagar learned five languages — Latin, German, Italian, Catalan and Occitan — making 10 languages that he knows in total (for now, at least).

In losing the history of pieces of music, Saagar says, we’ve lost languages and cultures that were present and important to the time period.

And today, at a time when linguistic boundaries are crumbling before our eyes, he says, instead of judging someone who speaks differently from you, realize that “it’s actually a way of speaking a language and that we should cherish that because it’s beautiful in its own way.”

Anne Brice: This is Berkeley Voices. I’m Anne Brice.

[Music: Saagar Asnani plays an excerpt from Bach’s Cello Suite No. 3 on the viola, then music fades down]

Saagar Asnani: I learned the viola starting in, I think, fourth grade. So starting since then. And then I was very active. I played in the Philadelphia Youth Orchestra and in as many orchestras as I possibly could. Every day of my week I had a rehearsal (laughs) in high school.

Anne Brice: Saagar Asnani is a Ph.D. candidate in musicology and in medieval studies at UC Berkeley. He has been playing in UC Berkeley’s Symphony Orchestra since he first joined the campus in fall 2020.

[Viola music comes up, then ends]

Since he was a kid, music and language have been central to Saagar’s life.

Saagar Asnani: I started speaking Hindi when I was a child. I grew up in a Hindi-speaking household. So my day-to-day interactions would be this fun mixture of Hindi, English, and sometimes, because in India, every family also has, like, their own dialect or regional variety of a language that they speak. And so Sindhi was what my parents spoke.

Anne Brice: His parents and two older brothers came to the U.S. from India in 1992, and Saagar was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, four years later.

Saagar Asnani: I wouldn’t even register if one of my family members said half a sentence in one language and then completely switched for the other half.

Oftentimes, we even do the thing of, like, you take a Hindi verb, then you add in -ifying, or some kind of English morphological suffix, like -est, to it in order to make it work in an English sentence. So (laughs) we do that very often.

One humorous example is “bakwas” means, like, BS, or you’re talking garbage. So we say we’re “bakofying” — we’re talking BS. (Laughs)

I don’t think anyone except our family does that … does that particular word, right? Each family has their own variety of words.

Anne Brice: During college at the University of Pennsylvania, Saagar spent a semester abroad in Lyon, France, where he took classes on the history of medieval literature and on medieval music.

Saagar Asnani: I started to see connections between the fact that all the music that I was studying in the Renaissance era and the Middle Ages had a very close connection to the texts I was studying in my literature courses. And so I started to see, even in undergrad, these kind of tendrils poking at each other.

Anne Brice: And now, in his research at Berkeley, Saagar is looking at songs written in medieval Europe, particularly between the 12th and 14th centuries in France. And in these music manuscripts, he looks for evidence of linguistic variation and dialectical differences from the kind of standard Parisian that we consider to be modern French today.

[Music fades out]

He says only recently have scholars begun to use a wider variety of media and artistic expressions as a way to study language.

Saagar Asnani: The traditional thing has always been literature, right? They’d use Chrétien de Troyes. They’d use these novels. They’d use also poetry, which is not set to music. They’d use, like, the Lais of Marie de France, which are these, kind of, narrative poems, basically. And so all of that was kind of like the traditional source type for linguists.

But in the past, like, four or five years, actually even longer than that, linguists have kind of moved out from just those traditional literary text types and have thought about, What happens if you talk about the press? What happens if we talk about legal documents? What happens if we talk about theater?

And if we unpack the genre of music, we will find a record of how, and actually a very precise record, of how language was spoken.

Anne Brice: Wow. Is it kind of a growing trend? Are more scholars starting to look at music in their work when studying language?

Saagar Asnani: At least for the field I’m in, medieval French historical-social linguistics? No, not at all. You know, this is kind of uncharted territory.

Anne Brice: Saagar says this kind of hegemony of Parisian French in music has become a little oppressive — even in the modern day.

Saagar Asnani: We have a lot of stories about L’Académie Française and how there’s very much one correct way to speak. It’s called “le bon usage,” and that’s a concept that dates back to the 17th century with Claude Favre de Vaugelas.

Anne Brice: Vaugelas was a French grammarian and original member of the Académie Française, who wrote a kind of meta-linguistic text on how to speak French well.

And in modern day linguistic interactions, says Saagar, we adhere to this idea that there’s a correct way to speak and write.

Saagar Asnani: If we rely on one authoritative version, which tends to be Parisian, of a text, then we lose a lot of the entire kind of transmission history and circulation of these pieces of music.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: And in losing the history of pieces of music, he says, we’ve lost languages and cultures that were present and important to the time period. One example is Occitan, a language from medieval Europe. Many of the songs that Saagar has been using in his research are written in Occitan.

Saagar Asnani: If I describe it in very, very reductive terms, it’s as if French and Italian had a baby (laughs) — French, Italian and Spanish. It’s kind of a weird mixture of all three. It was spoken very widely in what is now southwestern France — Auvergne, Toulouse, Poitiers, these cities, even stretching into the center part of the country.

It was also kind of the main language and it was the culture, like, we call “the French,” you would have called people who spoke Occitan “the Occitanians.” They were the Occitan people. And so this is a very high-prestige culture, actually, in the 11th through 13th centuries in what is now southern France. And in fact, the first vernacular poetry, musical poetry, by the troubadours was in Occitan.

[Music: “The Gran Dias” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Anne Brice: During the Albigensian Crusade of 1209, the French monarchy took over what was then called Occitania.

Saagar Asnani: So after that, there was this kind of linguistic and textual appropriation of Occitan language texts by French authors. Back then they weren’t really thinking of constructing a corpus of things to call French. They weren’t thinking in terms of, like, “Oh, this is the history of the French language and poetry.”

But that appropriation, the mixture of French and Occitan language in manuscripts containing Occitan song, basically led down the road to this kind of historical appropriation of Occitan culture as French.

Scholars already have traced that citation to this manuscript, which contains troubadour Occitan song, but with French influence. Eliza Zingesser has written a really good book, Stolen Song: How the Troubadours Became French, on this. She’s a professor at Columbia.

Anne Brice: To read the different languages in music manuscripts from medieval Europe, Saagar has added a few more languages to his repertoire.

To read Occitan, rarely taught in universities, he took Catalan — a close linguistic relative to Occitan. He also took Latin, German and Italian and is proficient to varying degrees in each.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: Last year, Saagar gave a talk on a paper he wrote at the inaugural meeting of the Bay Area Early Music Consortium.

Saagar Asnani: The title of my paper was, “The Curious Case of ‘mi doint’: A Sociolinguistic analysis of a Hybrid-Occitan-French Motet.”

Anne Brice: A motet is a style of vocal composition that has gone through numerous transformations over many centuries. So in this motet that Saagar looked at, there were four different versions.

Saagar Asnani: So what we realized was that one version, “Montpellier,” which is like the most authoritative Parisian source, is also already revised in the Middle Ages. It’s a version which is not the original.

Anne Brice: And the three others contained non-Parisian regional dialects, including words in Picard and Occitan.

Saagar Asnani: And so that’s a transmission of history of this one piece, that if you pay attention to those variants that get actually in a scholarly edition, totally wiped out. The only thing that’s left is the “Montpellier” version. In fact, most editions present the “Montpellier,” and they actually reject readings of many of those words, based on the “Montpellier” version.

[Music: Saagar plays Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata on the viola]

And so what we get at the end is the idea that, “This is our authoritative version, this is the correct way to sing it and to perform it.” But that implicitly underlines, it reinforces the idea that this motet was Parisian, which none of the other evidence actually seems to bear the case for.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: What do you take away from that? When you’re looking at the big picture when you discover these things, what does that tell you about all the songs and the language that we know as kind of the right way or how it should be? And how do you apply it to your understanding of other music and language?

Saagar Asnani: Yeah. I mean, part of what it kind of lays bare is the effect of both pedagogy and tradition on the verification of what becomes a standard and then hegemonic standards of that standard, right?

Vocal pedagogy, in particular, is known for having teachers berate their students for pronouncing things certain ways.

There’s a book by scholar Katherine Bergeron, Voice Lessons in Belle Époque France [Sic: Voice Lessons: French Mélodie in the Belle Époque], and there she talks about how particular styles of singing were denigrated as being not correct or not the way to sing. And that led to a particular style of singing that became dominant over the course of the 20th century.

And the way that we hear music today is certainly not indicative of how music would have been. We can’t just pick up a recording on YouTube and assume that’s how it might have sounded. Every performer brings their own biases, ideas and traditions to the fore when they perform something.

But also, when we’re talking about tradition and standard, not just in the realm of music performance, but also then in the realm of speaking different varieties of languages. Right?

And so this idea of the proper language has both ramifications on the stuff that we study from the past, but also on our day-to-day interactions today.

Language-based algorithms are increasingly crucial to the way that we live today, both on our subscription models and on the rise of artificial intelligence. But if you’re going to base all of these ideas on a standardized way of speaking, it kind of effaces a whole history of linguistic variation.

I just wonder what is to come in the future, of how the computer will basically verify and make us all sound the same, make us all speak the same way, when that’s just certainly not how humans work and interact and communicate in the first place.

[Music fades out]

Anne Brice: What do you hope are the takeaways that other people learn from your research?

Saagar Asnani: One, is a really close investment with primary sources. And not to take someone’s word for a historical account or a narrative, but to actually go back and do the research by actually looking at whatever aspect of the original source that we can.

We’re blessed to have so many manuscripts put up online and digital images today, which allows me sitting here in California to make such a detailed account of manuscripts that are sitting in Europe without actually ever having gone there. That’s not to say I don’t want to go there to actually see them, because that’s also crucial.

But the stakes of what we can do today in a digital age, where all this is accessible, makes it all the more imperative that we do that work in order to understand where our biases are coming from, where our ideas of what is standard, what is not, to question those narratives.

And to think about language as not something which we have to constantly correct each other and be like, “Oh, you spoke this wrong. You said this past tense in the wrong way.” But rather to accept different varieties of languages, especially in a world where today we have both national and linguistic boundaries kind of crumbling before our very eyes, right? Not in a bad way, but in an idea that we have so much more communication across them.

And so when someone comes to you speaking with an accent you don’t recognize, or with a prosody and a rhythm to their language that seems kind of off to you, don’t be so quick to judge them. But rather, accept that they’re trying to learn and speak the language of you and trying to communicate with you on your terms.

But also that that’s actually a way of speaking a language and that we should cherish that because it’s beautiful in its own way.

[Music: “Littl Jon” by Blue Dot Sessions]

And in the same vein, when you go abroad or you go somewhere, you also take an effort to learn at least the basics. Learn how to communicate with those around you, because you’ll get so much more out of the experience. Not trying to rely on translation apps, though those are everywhere, but actually engaging with the different sounds around you.

I find in all of my travels, I always try to learn some of the language before I go. And that’s what has also led to some of my language learning is that every time I know what people are saying around me or I can at least try, I’m welcomed more, I feel like I’m in a place where I want to be, rather than in a place where I’m just kind of an outsider.

And so, yeah. Those are some of the large-level takeaways that might come across in my very niche project. (Laughs)

Anne Brice: I’m Anne Brice, and this is Berkeley Voices, a Berkeley News podcast from the Office of Communications and Public Affairs at UC Berkeley. You can find all of our podcast episodes on Berkeley News at news.berkeley.edu/podcasts.

[Music fades out]

Saagar Asnani: … we’re playing right now, let’s see if I can remember.

[Music: Saagar plays Bowen’s Viola Sonata No. 1 in C Minor on the viola]

Saagar Asnani: It gets harder after that. (Laughs)

Anne Brice: That’s awesome!

Read a written version of “Medieval song holds clues to lost dialects”:

“I learned the viola starting in, I think, fourth grade,” said Saagar Asnani, a Ph.D. candidate in musicology and in medieval studies at UC Berkeley.

“So starting since then. And then I was very active. I played in the Philadelphia Youth Orchestra and in as many orchestras as I possibly could. Every day of my week I had a rehearsal in high school.”

Asnani has been playing in UC Berkeley’s Symphony Orchestra since he first joined the campus in fall 2020. Since he was a kid, music and language have been central to his life.

Courtesy of Saagar Asnani

“I started speaking Hindi when I was a child,” said Asnani. “I grew up in a Hindi-speaking household. So my day-to-day interactions would be this fun mixture of Hindi, English, and sometimes, because in India, every family also has, like, their own dialect or regional variety of a language that they speak. And so Sindhi was what my parents spoke.”

His parents and two older brothers came to the U.S. from India in 1992, and Asnani was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, four years later.

“I wouldn’t even register if one of my family members said half a sentence in one language and then completely switched for the other half,” he said.

“Oftentimes, we even do the thing of, like, you take a Hindi verb, then you add in -ifying, or some kind of English morphological suffix, like -est, to it in order to make it work in an English sentence. So we do that very often.

“One humorous example is “bakwas” means, like, BS, or you’re talking garbage. So we say we’re “bakofying” — we’re talking BS.

“I don’t think anyone except our family does that … does that particular word, right? Each family has their own variety of words.”

During college at the University of Pennsylvania, Asnani spent a semester abroad in Lyon, France, where he took classes on the history of medieval literature and on medieval music.

“I started to see connections between the fact that all the music that I was studying in the Renaissance era and the Middle Ages had a very close connection to the texts I was studying in my literature courses,” Asnani said. “And so I started to see, even in undergrad, these kind of tendrils poking at each other.

And now, in his research at Berkeley, Asnani is looking at songs written in medieval Europe, particularly between the 12th and 14th centuries in France. And in these music manuscripts, he looks for evidence of linguistic variation and dialectical differences from the kind of standard Parisian that we consider to be modern French today.

He said only recently have scholars begun to use a wider variety of media and artistic expressions as a way to study language.

Courtesy of Saagar Asnani

“The traditional thing has always been literature, right? They’d use Chrétien de Troyes. They’d use these novels. They’d use also poetry, which is not set to music. They’d use, like, the Lais of Marie de France, which are these, kind of, narrative poems, basically. And so all of that was kind of like the traditional source type for linguists.

“But in the past, like, four or five years, actually even longer than that, linguists have kind of moved out from just those traditional literary text types and have thought about, What happens if you talk about the press? What happens if we talk about legal documents? What happens if we talk about theater?

“And if we unpack the genre of music, we will find a record of how, and actually a very precise record, of how language was spoken.”

“Wow. Is it kind of a growing trend?” I asked. “Are more scholars starting to look at music in their work when studying language?”

“At least for the field I’m in, medieval French historical-social linguistics? No, not at all. You know, this is kind of uncharted territory.”

Asnani said this kind of hegemony of Parisian French in music has become a little oppressive — even in the modern day.

“We have a lot of stories about L’Académie Française and how there’s very much one correct way to speak,” Asnani said. “It’s called “le bon usage,” and that’s a concept that dates back to the 17th century with Claude Favre de Vaugelas”

Vaugelas was a French grammarian and original member of the Académie Française, who wrote a kind of meta-linguistic text on how to speak French well.

And in modern day linguistic interactions, said Asnani, we adhere to this idea that there’s a correct way to speak and write.

“If we rely on one authoritative version, which tends to be Parisian, of a text, then we lose a lot of the entire kind of transmission history and circulation of these pieces of music.”

And in losing the history of pieces of music, he said, we’ve lost languages and cultures that were present and important to the time period. One example is Occitan, a language from medieval Europe. Many of the songs that Asnani has been using in his research are written in Occitan.

Courtesy of Saagar Asnani

“If I describe it in very, very reductive terms, it’s as if French and Italian had a baby — French, Italian and Spanish,” said Asnani. “It’s kind of a weird mixture of all three. It was spoken very widely in what is now southwestern France — Auvergne, Toulouse, Poitiers, these cities, even stretching into the center part of the country.

“It was also kind of the main language and it was the culture, like, we call “the French,” you would have called people who spoke Occitan ‘the Occitanians.’ They were the Occitan people. And so this is a very high-prestige culture, actually, in the 11th through 13th centuries in what is now southern France. And in fact, the first vernacular poetry, musical poetry, by the troubadours was in Occitan.

During the Albigensian Crusade of 1209, the French monarchy took over what was then called Occitania.

“So after that, there was this kind of linguistic and textual appropriation of Occitan language texts by French authors,” said Asnani. “Back then they weren’t really thinking of constructing a corpus of things to call French. They weren’t thinking in terms of, like, “Oh, this is the history of the French language and poetry.

“But that appropriation, the mixture of French and Occitan language in manuscripts containing Occitan song, basically led down the road to this kind of historical appropriation of Occitan culture as French.

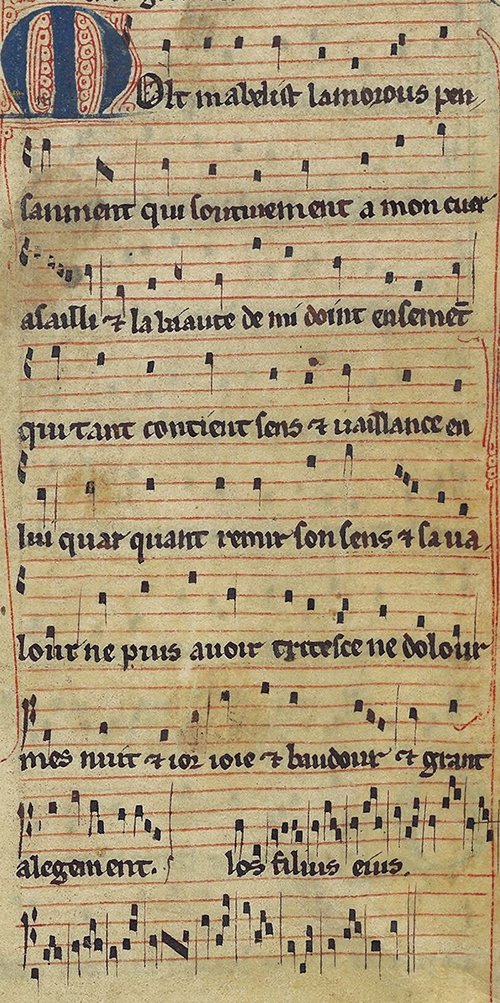

“Scholars already have traced that citation to this manuscript, which contains troubadour Occitan song, but with French influence. Eliza Zingesser has written a really good book, Stolen Song: How the Troubadours Became French, on this. She’s a professor at Columbia.”

To read the different languages in music manuscripts from medieval Europe, Asnani has added a few more languages to his repertoire.

To read Occitan, rarely taught in universities, he took Catalan — a close linguistic relative to Occitan. He also took Latin, German and Italian and is proficient to varying degrees in each.

Last year, Asnani gave a talk on a paper he wrote at the inaugural meeting of the Bay Area Early Music Consortium. The title of his paper was, “The Curious Case of ‘mi doint’: A Sociolinguistic analysis of a Hybrid-Occitan-French Motet.”

A motet is a style of vocal composition that has gone through numerous transformations over many centuries. So in this motet that Asnani looked at, there were four different versions.

“So what we realized was that one version, ‘Montpellier,’ which is like the most authoritative Parisian source, is also already revised in the Middle Ages,” said Asnani. “It’s a version which is not the original.”

And the three others contained non-Parisian regional dialects, including words in Picard and Occitan.

BNF Gallica Archive

“And so that’s a transmission of history of this one piece, that if you pay attention to those variants that get actually in a scholarly edition, totally wiped out,” he said. “The only thing that’s left is the ‘Montpellier’ version. In fact, most editions present the ‘Montpellier,’ and they actually reject readings of many of those words, based on the ‘Montpellier’ version.

“And so what we get at the end is the idea that, “This is our authoritative version, this is the correct way to sing it and to perform it.” But that implicitly underlines, it reinforces the idea that this motet was Parisian, which none of the other evidence actually seems to bear the case for.”

“What do you take away from that?” I asked. “When you’re looking at the big picture when you discover these things, what does that tell you about all the songs and the language that we know as kind of the right way or how it should be? And how do you apply it to your understanding of other music and language?”

“Part of what it kind of lays bare is the effect of both pedagogy and tradition on the verification of what becomes a standard and then hegemonic standards of that standard, right?” Asnani said.

“Vocal pedagogy, in particular, is known for having teachers berate their students for pronouncing things certain ways.

“There’s a book by scholar Katherine Bergeron, Voice Lessons in Belle Époque France [Sic: Voice Lessons: French Mélodie in the Belle Époque], and there she talks about how particular styles of singing were denigrated as being not correct or not the way to sing. And that led to a particular style of singing that became dominant over the course of the 20th century.

“And the way that we hear music today is certainly not indicative of how music would have been. We can’t just pick up a recording on YouTube and assume that’s how it might have sounded. Every performer brings their own biases, ideas and traditions to the fore when they perform something.

“But also, when we’re talking about tradition and standard, not just in the realm of music performance, but also then in the realm of speaking different varieties of languages. Right?

“And so this idea of the proper language has both ramifications on the stuff that we study from the past, but also on our day-to-day interactions today.

“Language-based algorithms are increasingly crucial to the way that we live today, both on our subscription models and on the rise of artificial intelligence. But if you’re going to base all of these ideas on a standardized way of speaking, it kind of effaces a whole history of linguistic variation.

“I just wonder what is to come in the future, of how the computer will basically verify and make us all sound the same, make us all speak the same way, when that’s just certainly not how humans work and interact and communicate in the first place.”

“What do you hope are the takeaways that other people learn from your research?” I asked.

“One, is a really close investment with primary sources,” said Asnani. “And not to take someone’s word for a historical account or a narrative, but to actually go back and do the research by actually looking at whatever aspect of the original source that we can.

Courtesy of Saagar Asnani

“We’re blessed to have so many manuscripts put up online and digital images today, which allows me sitting here in California to make such a detailed account of manuscripts that are sitting in Europe without actually ever having gone there. That’s not to say I don’t want to go there to actually see them, because that’s also crucial.

“But the stakes of what we can do today in a digital age, where all this is accessible, makes it all the more imperative that we do that work in order to understand where our biases are coming from, where our ideas of what is standard, what is not, to question those narratives.

“And to think about language as not something which we have to constantly correct each other and be like, “Oh, you spoke this wrong. You said this past tense in the wrong way.” But rather to accept different varieties of languages, especially in a world where today we have both national and linguistic boundaries kind of crumbling before our very eyes, right? Not in a bad way, but in an idea that we have so much more communication across them.

“And so when someone comes to you speaking with an accent you don’t recognize, or with a prosody and a rhythm to their language that seems kind of off to you, don’t be so quick to judge them. But rather, accept that they’re trying to learn and speak the language of you and trying to communicate with you on your terms.

“But also that that’s actually a way of speaking a language and that we should cherish that because it’s beautiful in its own way.

“And in the same vein, when you go abroad or you go somewhere, you also take an effort to learn at least the basics. Learn how to communicate with those around you, because you’ll get so much more out of the experience. Not trying to rely on translation apps, though those are everywhere, but actually engaging with the different sounds around you.

“I find in all of my travels, I always try to learn some of the language before I go. And that’s what has also led to some of my language learning is that every time I know what people are saying around me or I can at least try, I’m welcomed more, I feel like I’m in a place where I want to be, rather than in a place where I’m just kind of an outsider.

“And so, yeah. Those are some of the large-level takeaways that might come across in my very niche project.”