In pursuit of a poison frog — and a culturally appropriate name

UC Berkeley’s Rebecca Tarvin and Colombian colleagues tracked down a new species along that country's Pacific coast, naming it in honor of an Afro-Colombian music style.

February 10, 2025

La versión en español de este artículo está disponible aquí.

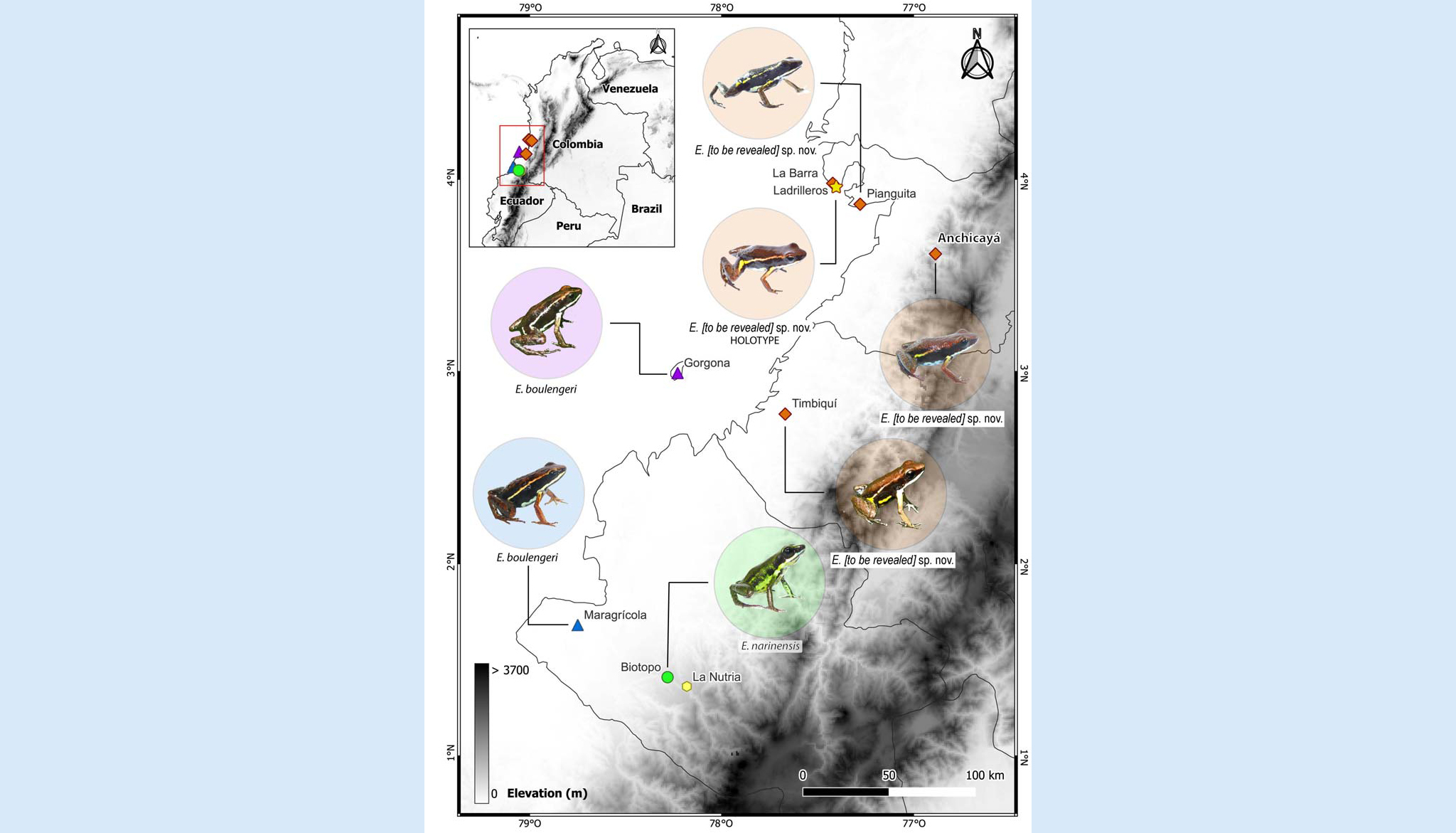

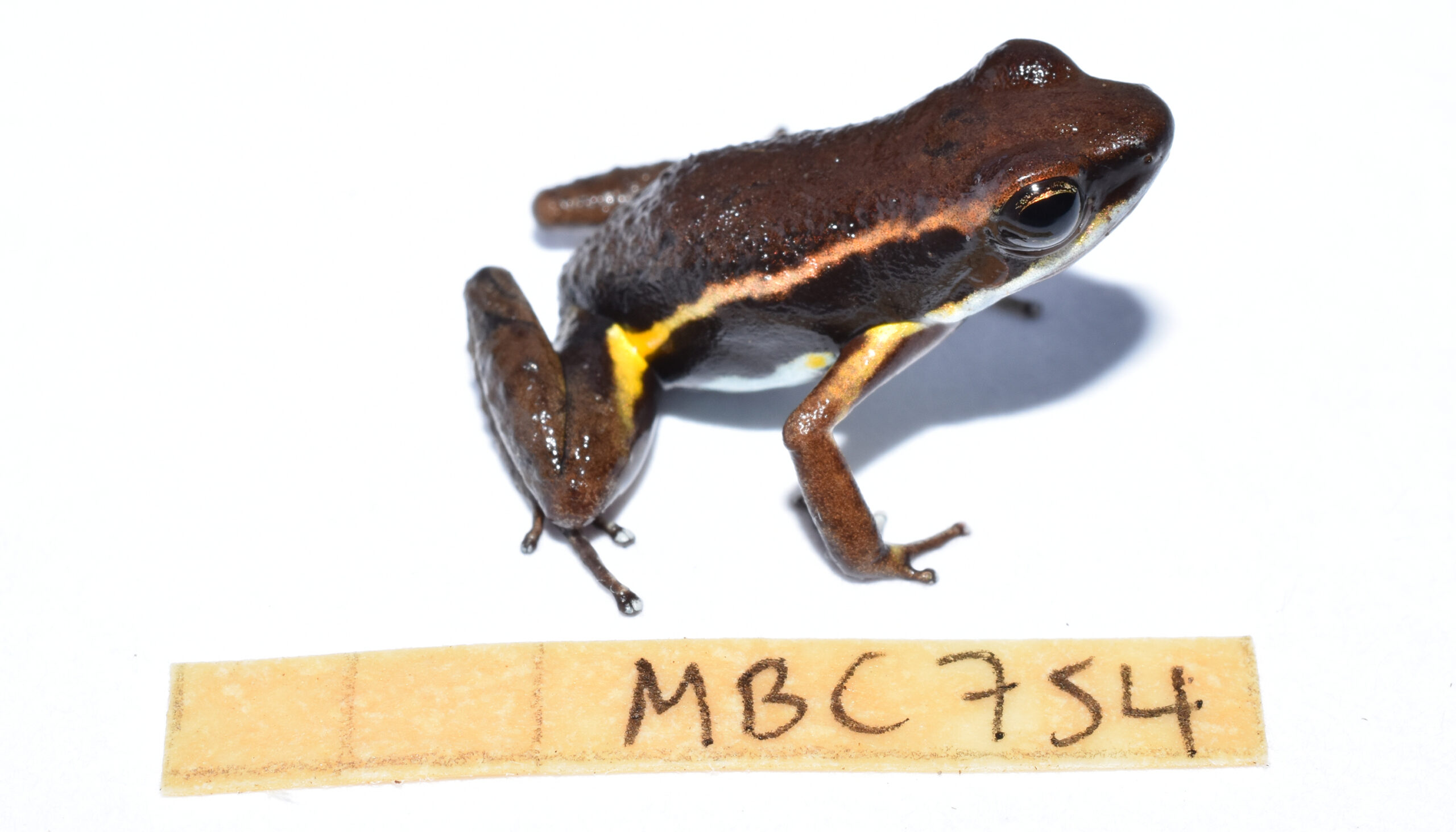

When Rebecca Tarvin was a graduate student studying toxins in the skins of poisonous frogs, she and her colleague Mileidy Betancourth-Cundar collected a frog in Colombia that they suspected was a new species. It differed in coloration from a similar Colombian frog in the genus Epipedobates and had a different mating call.

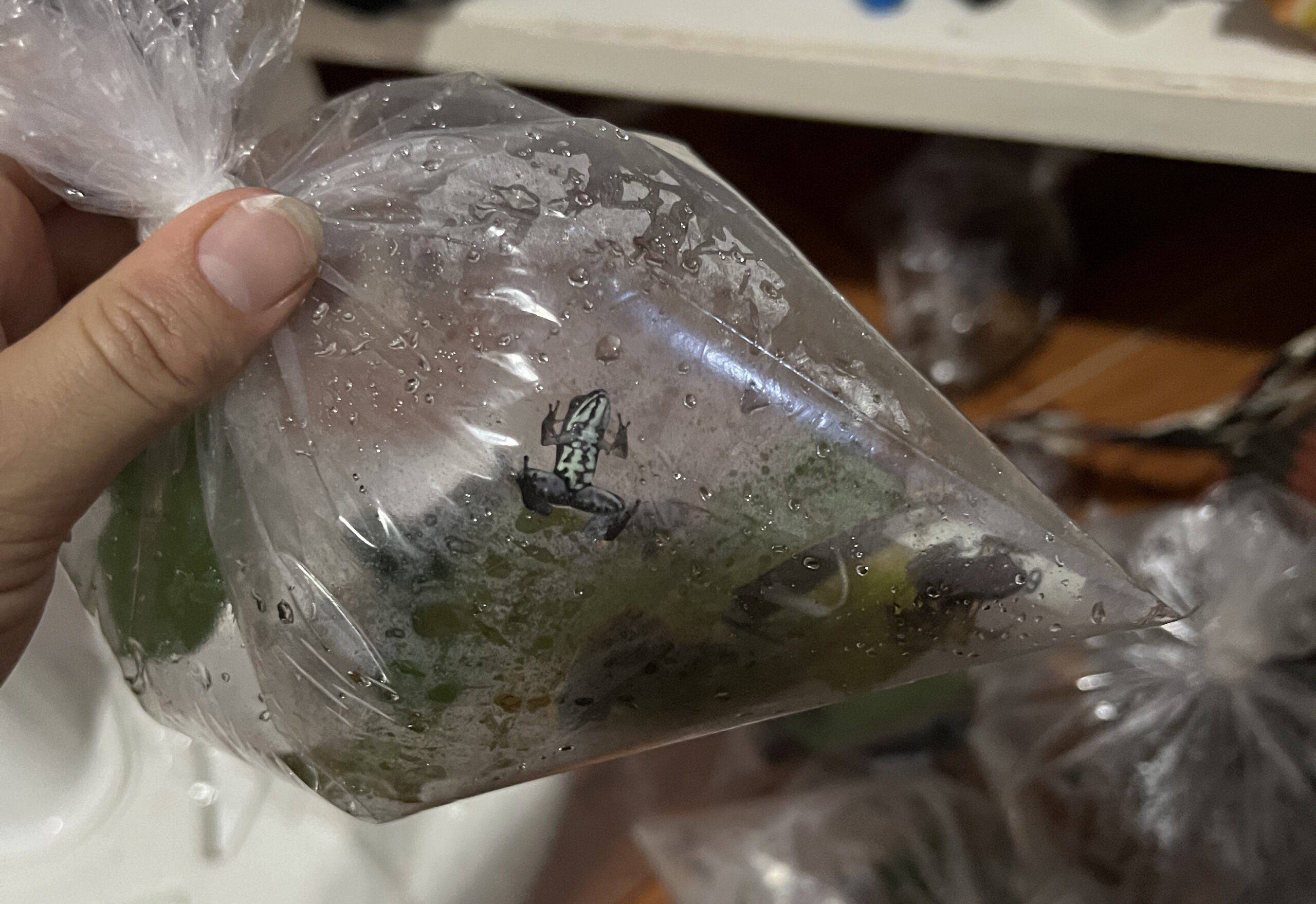

In 2022, eight years later and a newly appointed assistant professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley, Tarvin met up with Colombian biologists to collect more of these frogs and confirm a new species. Such “holotype specimens” are necessary to document a new species for posterity. Collecting specimens and identifying new species also helps scientists track the impact of environmental changes and understand the evolutionary origin of traits such as skin toxins, which may one day have medical uses.

Collecting the frogs was easy; they seem to thrive along roadsides and in semiurban areas. But what to name the species? A Colombian colleague played for the team a tape of local marimba-based music called bambuco, and one style, called bambuco viejo, or currulao, stood out. The name Epipedobates currulao seemed appropriate, and with this month’s publication of a paper describing the new species in the journal ZooKeys, it’s now official.

Currulao (koo-roo-LAO), which combines marimbas and drums, is popular in black communities along Colombia’s Pacific coast. Check out a performance on YouTube by Cantadoras del Pacifico at the 2009 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

“We ended up going with currulao because we liked how it brought in the human perspective,” Tarvin said. “The frog is part of the sound landscape; when they call, it’s part of the background noise in the region. Similarly, currulao is more than just a genre of music. It’s also the cultural practices around the music, the gathering, dancing and the relationship-forming aspects of the experience.”

Tarvin is still investigating the toxins produced by frogs in the genus Epipedobates, which is small, containing about eight species, but is the most recently evolved group of poisonous frogs in South America. By comparing the genetics of these frogs with other poison frog groups, she hopes to understand how their chemical defense technique evolved. Most poisonous animals are brightly colored to advertise their unpalatability, such as the Monarch butterfly’s bright orange color and the gaudy orange, black and blue of poison dart frogs. But Epipedobates frogs are more subtly colored, if not downright drab. Perhaps, she said, bright coloration evolves after the frogs develop their toxic defenses.

Epipedobates acquired its chemical defenses more recently than any other group in the poison frog family and shows the largest range in color and defense, Tavin said, but they’re also interesting because of how they acquire their toxicity.

“What’s unique about poison frogs, specifically, is that they sequester toxins from their food, so it’s an entirely different kind of defense that requires an entirely different physiology, compared to venom-producing animals, like snakes and bees,” she said. “Poison frogs eat arthropods that have small amounts of chemicals that can be either toxic or distasteful. And then they accumulate those to levels that become relevant for their own predators.”

Tarvin offers one piece of advice: Because they’re covered in poisons, don’t lick your fingers after picking one up.