How activism has brought me closer to my ‘Madar’ and my heritage

In remembering her grandmother, human-rights fellow Rochelle Terman — a grad student of mixed Muslim-Iranian and Jewish-American roots — discovers how her attraction to human-rights work relates to her own complex heritage.

July 9, 2010

COLUMBUS, OH — My sister got married a couple years ago. My grandmother came to the United States from Iran for the wedding, and asked me when I would walk down the aisle.

Each year the UC Berkeley-based Human Rights Center awards summer fellowships to students from University of California campuses, to enable them to work with human-rights organizations in the U.S. and abroad. Three current Human Rights Fellows have agreed to share their experiences this summer, with regular updates from the field to be published on the NewsCenter. Rochelle Terman sends her first post from Montreal.

Each year the UC Berkeley-based Human Rights Center awards summer fellowships to students from University of California campuses, to enable them to work with human-rights organizations in the U.S. and abroad. Three current Human Rights Fellows have agreed to share their experiences this summer, with regular updates from the field to be published on the NewsCenter. Rochelle Terman sends her first post from Montreal.

Rochelle Terman

Rochelle Terman

on women living under Muslim laws

- Defending the rights of Muslim women is a highly charged minefield

- Violence against women in the name of ‘culture’ is pandemic

- How activism has brought me closer to my ‘Madar’ and my heritage

- A cousin’s bat mitzvah, and the tradition of defending our traditions by any means necessary

- A one-way path towards gender justice: The West leading the rest

- The aromas of Bali and the contours of a furious debate

- Reflections on a hijab-wearing Iranian feminist and how she touched my life

“Not for a while, Madar,” I responded in Persian. It wasn’t until I learned her “mother tongue,” in college, that I could really talk to my grandma — my “Madar.”

“Do you have a boyfriend?” As she asked this, I was leisurely perusing YouTube for videos of one of my favorite musical artists. I turned the computer screen around to show her my celebrity crush.

“This is my boyfriend, Madar. His name is Mos Def.”

“Mustafa?”

“No, Madar, Mos Def.”

“Mustafa is a Muslim name. Is he Muslim?”

“Well, yes, but … ”

“Veeeeery good.” She gazed off into the distance, no doubt picturing the beautiful children that I and Mustafa would have.

Truth be told, my mamabozorg (literally,”big mama”) didn’t care whom I married. Although she is a devout Muslim, her religious beliefs did not prevent her from being happy when my mother married a Jewish man, or when my sister married her Christian boyfriend. Now it appeared that any prospective partner was acceptable — as long as he was smart, kind, and tall.

I also got the distinct feeling that Madar would not object if I happened never to get married. Her own marriage came early, at 13 or 14. Whatever her exact age, it was premature even by Iranian standards — where the minimum age of marriage, at the time, was 18. (After the wedding, Madar’s original birth certificate was never to be found again.)

For a woman who has been married for about 70 per cent of her life, my grandmother is remarkably independent. Even in a foreign country, the U.S., she seems quite content taking long walks alone, along the way categorizing all the plant life.

When hanging out at my parent’s house, she usually watches The Ellen DeGeneres Show. Although she can’t understand a word (so keeps it on “mute”), I think she likes the fact that Ellen dresses in long sleeves — a refreshing display of “modesty,” for cable TV. When my sister and I informed Madar than Ellen had a wife, she looked at us as if we’d said that Martians had just landed on our front porch and offered to bake us croissants. Soon after, she turned off Ellen. We didn’t object; she’s a babushka-wearing grandma from the old country, after all. But a few weeks later, we found her watching the show again. Now whenever gay marriage comes up in conversations, Madar murmurs “like Ellen” under her breath, as if remembering an old friend.

The political and the personal

You may be wondering what my grandmother’s quirks have to do with my experiences as a human-rights intern. Well, I’ve been spending a lot of time with my grandmother lately — and revisiting questions that have been on my mind since before my internship began: how do people come to political activism, and what draws us to particular social-justice issues?

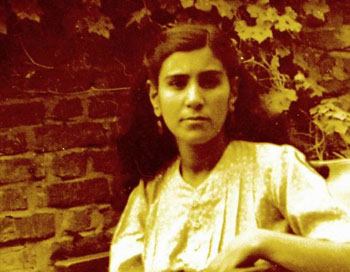

"Madar" as a young woman. (Courtesy of Rochelle Terman)

Many, I think, first become interested in human-rights topics by virtue of their family relationships, personal heritage, or cultural identity. The personal becomes political. But for me it’s been the other way around. I only really got to know my family, my heritage, and my cultural belonging by virtue of my human-rights activities and studies.

I learned Persian primarily through my advocacy work, and it was only then that I could communicate with my grandmother in a meaningful way. My interest in women’s human rights in Iran led me to my mother’s birthplace and to busloads of relatives there. My academic work on Muslim countries opened up a world of traditions, rituals, and cultural practices that had been invisible to me as a suburban American teenager.

Sure, I always said I was interested in Iranian women’s rights because of my heritage. But that was an easy explanation — something I felt that people expected to hear. In truth, I couldn’t really articulate how I became committed to this issue. It was ineffable, like a craving for guacamole. How do you get a craving for guacamole? I don’t know, you just do.

But after spending quality time recently with Madar, I’m starting to better understand my previously elusive motivations.

My human-rights activities provided me the tools and opportunities to finally connect with my grandmother directly, without a translator or postal service. When I did, I noticed that nothing ever seemed to upset her. She lived life with the kind of perspective that comes with a lifetime of immense hardship: her parents died when she was a child, leaving her to raise her younger brother alone; by the age of 20, she had had four children; with no formal education, she brought them up in a time of intense political turmoil in Iran.

Madar told me these things during our long afternoon conversations, drinking hot tea with sugar cubes in our mouths. I sensed my Persian improving during the course of our interactions, as I struggled to keep up with the names and dates and descriptions. Sometimes she went off on a tangent, counting how many of her granddaughters are now lawyers, doctors, or scholars. “Yek, do, se…” “There are many.” How much did she sacrifice to get us where we are?

Connecting with those who came before

I’ve come to believe that everyone who does activism feels a certain level of guilt — over having it better than their grandparents, over having benefited from the sweat of their ancestors. This is not to say that all activists are bourgeois or have never had to struggle themselves. But I do think that continuing what your predecessors started brings a sense of connection with those people. No doubt students protesting outside Sproul Hall today are thinking of their predecessors in the ’60s Free Speech Movement, and youth demonstrators of Iran’s Green Movement are harking back to the mothers and grandmothers of the Islamic and Constitutional Revolutions. I feel this sense of continuation, too, in my activism — even though my grandmother would be happy if, instead of all this, I settled for baking pies in my suburban home with my handsome boyfriend Mustafa.

I sometimes wonder if my activism is just a selfish ploy to rid myself of yuppie guilt. Yet at the same time, I can’t help feel that the more I sacrifice for this cause, the more connected I am with Madar and with my heritage. My grandmother — a one-time child bride, denied access to formal education, subject to draconian political and religious ideologies — personifies, in many ways, the issues that are my passion.

My human rights activities have allowed me to see my grandmother not as an abstract case but as my grandma — loving, funny, eccentric. She’s deathly afraid of dogs (running away from the smallest poodle), but can look a roaring lion in the eye in its shoddy zoo cage without a shudder. She loves pad thai and a chipotle burrito. She haggles over ten-cent postcards and hides her prayer beads, like a Middle Eastern dreamcatcher, under her pillow. Yes, she’s the product of severe social and political circumstance, but she’s also a wonderful, complex human being who has made a good life for herself and her progeny, and is utterly content with her relationship to God, family, and country.

I realize now that I am drawn to human-rights issues not only because of my personal heritage but as a way to comprehend that heritage. My activism has given me more than just a line for my resumé or a warm, fuzzy feeling. Quite literally, it’s given me a family. In the midst of the political, I’ve managed to discover the personal.

About Rochelle Terman

The daughter of a Muslim-Iranian mother and Jewish-American father, Rochelle Terman became interested in women’s rights in Iran while an undergraduate at the University of Chicago studying political science and Near Eastern studies. During that time, Terman did a summer internship at Women Living Under Muslim Laws — an international solidarity network for women whose lives are shaped by laws and customs said to derive from Islam — and helped to found the Global Campaign to Stop Killing and Stoning Women (SKSW).

Now a graduate student at Berkeley focusing on political science, Terman, 24, will spend the summer researching and documenting success stories of local women’s organizations located in seven countries — Afghanistan, Indonesia, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal and Sudan — as part of her continued work with SKSW.