L&S ‘Big Ideas Courses’ aim to inspire faculty, students alike

According to Executive Dean Mark Richards, the concept for the program grew out of long-range plans in L&S to enhance the undergraduate curriculum. Big Ideas Courses allow undergrads not only to delve into important issues from multiple viewpoints, but also to fulfill their requirements in new and interesting ways.

November 30, 2012

What happens when you bring together some of the campus’s best professors — from completely different disciplines — one “big idea” and a room full of bright Berkeley undergraduates?

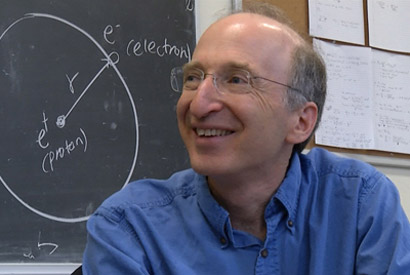

Among those who will be teaching a Big Ideas Course this spring is Saul Perlmutter, winner of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics. (Jon Schainker photo)

That’s just what the College of Letters and Science plans to find out this spring, when it will launch five innovative new “Big Ideas Courses” on topics spanning the breadth of the liberal arts.

According to Executive Dean Mark Richards, the concept for the program grew out of long-range plans in L&S to enhance the undergraduate curriculum. Big Ideas Courses allow undergraduates not only to delve into important issues from multiple viewpoints, but also to fulfill their requirements in new and interesting ways.

“We want our students to take on fundamental, even risky, intellectual challenges as part of their core experience here,” says Richards, “and that’s something that Berkeley does best.”

Richards also points with pride to the faculty’s overwhelming support for Big Ideas, driven by their enthusiasm for teaching undergraduates and their appreciation for greater cross-disciplinary co-teaching opportunities. “Big Ideas Courses,” he explains, “offer our faculty new degrees of freedom in exploring the boundaries of their own teaching and scholarship.”

Statistics professor Philip Stark, who gathered no fewer than five colleagues to co-teach a course called “Societal Risks and the Law,” praises the initiative as “the academy at its best, providing a chance to participate in cross-disciplinary scholarship with profound societal implications. The breadth of expertise, experience, and perspectives is thrilling.”

Kevin Padian, a professor of integrative biology scheduled to co-teach “Origins in Science and Religion” with Near Eastern studies professor Ron Hendel, agrees. “We’re so excited about this course, which addresses how people think about the most fundamental life questions,” Padian says. “Through this conversation, both science and the humanities can retain their characteristic ways of looking at the world, while conceding some points and learning new ways to think about old problems.”

One hallmark of the new program will be the lively interchanges among faculty with sharply differing academic backgrounds. In contrast to tag-team teaching, Big Ideas Courses will feature true co-teaching, with both instructors in the classroom — and interacting — during every class period.

The format is designed to inspire faculty to create “the dream class we would have loved to take when we were students,” says Rob MacCoun, a professor of public policy and law. “If students learn half as much as we’re learning designing the course — or have at least half as much fun — the class will be a big success.”

In MacCoun’s case that “dream class” is “Sense and Sensibility and Science,” which he’ll co-teach with philosophy professor John Campbell and Saul Perlmutter, winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics. For Campbell, a troubling line of thought lies at the core of the course.

“Being in a democracy means that everyone’s point of view matters as much as anyone else’s,” he explains. “But belief in science means there’s just one right answer. So you can’t have science in a democracy.” The class, he says, will address the thorny question of “how science should be input into group-decision making on topics that matter.”

Perlmutter believes the methodologies of problem-solving and self-critical scientific thinking should be useful for everyone, scientist or not. “But when put in a group, even scientists have a hard time doing rational decision-making and planning,” he says. “Could a physicist, a philosopher and a public-policy social psychologist find a way to explore these problems? And can a democratic society better use the rationality of science? We’ll find out.”

Other spring Big Ideas Courses include “Music and Meaning,” co-taught by Hannah Ginsborg (philosophy) and Mary Ann Smart (music), and “Time,” co-taught by Raphael Bousso (physics) and Hubert Dreyfus (philosophy).

As for Richards, he isn’t sure who will benefit more from the new program — participating faculty or the undergrads in their classes — but confidently predicts the Big Ideas Courses “will inspire learning and debate across the board.”