Modern Icelandic gets warm reception as latest Berkeley language

From Vikings to contemporary transatlantic travelers and today's students, Icelandic lives on.

August 25, 2015

Modern Icelandic is a language spoken fluently by about 320,000 of the world’s more than 7 billion inhabitants, and now more maybe be speaking it as UC Berkeley offers it as a regular course for the first time this fall.

The idea is to facilitate Berkeley students’ work on Iceland by relating to the language made legendary by Viking sagas about the explorers’ ninth-century settlement of the island on the southern edge of the Arctic Circle.

Jackson Crawford says Tyrannosaurus rex in Icelandic is “grameðla,” or “king lizard.” “Gram” is the name of the sword of the hero of the Saga of the Volsungs, so the dinosaur’s name can be read as “(famous) sword lizard,” an image evoking its formidable teeth. (UC Berkeley photo by Jeff Wason.)

The UC Berkeley Department of Scandinavian and Institute of European Studies (IES) are co-sponsoring the beginning language instruction in back-to-back, fall and spring semesters, joining two other universities in the United States that teach Modern Icelandic. Modern Icelandic is also offered at Brigham Young University in Utah, according to Chip Oscarson, head of BYU’s Scandinavian Studies program and a Berkeley alumnus. The University of Minnesota sends students to the University of Iceland for three weeks of a six-week summer course on the language.

Strategic connections

Despite the small number of speakers of Modern Icelandic – most of whom live in Iceland, Canada or the United States –the IES calls Modern Icelandic “a strategic language in transatlantic connections between the U.S. and Europe, as well as between Europe and the Arctic.”

IES director Jeroen Dewulf notes that Modern Icelandic was one of the few Western European languages not yet offered on campus and will strengthen the Department of Scandinavian and enhance Berkeley’s recently established Nordic Studies Program. The institute also notes that the language is the mother tongue of one of the wealthiest, most developed nations in the world, albeit a small one.

A global perspective

“With globalization, we’re encountering people with other languages and cultures all the time, and seeing that the world … looks different when we step out of an English-language perspective.” Richard Kern, Berkeley Language Center.

Mark Sandberg, chair of Berkeley’s Department of Scandinavian when the course was assembled, says most non-Icelanders go to Iceland to learn the language. Berkeley’s introduction to the country’s language, literature and culture will prepare students for basic communication as well as a bit of the world they will encounter via their studies, or on arriving in Iceland for business, an archaeological expedition or other explorations.

Sandberg says the appeal of learning Icelandic may be enhanced by the island’s dramatic volcanic geography that is highlighted by glaciers and active volcanoes, and its globally recognized, vibrant and independent music scene, Viking history and reputation for keeping ferociously protective reins on its national language.

Only in Icelandic

Due to Iceland’s “language purism,” Modern Icelandic develops its own terms for everything from individual dinosaur species to obscure medical phenomena, says linguist-lecturer Jackson Crawford, who will teach Berkeley’s new Icelandic class to students on campus and those teleconferencing in from UCLA.

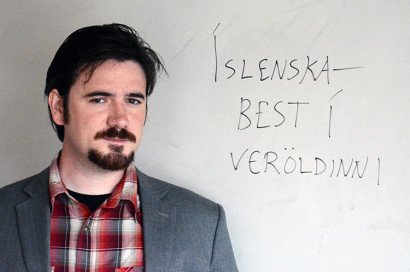

“Icelandic is the best in the world,” says the board behind linguist Jackson Crawford, who’s teaching Modern Icelandic this year. (UC Berkeley photo by Anne Brice)

“Even the wonders of modern technology are largely given their own unique words, rather than borrowing from English or other languages – a computer is ‘tölva’ (a conjunction of tala, which means number, and völva, a witch or female fortune teller),” he says about modern terms based on older, root words. “Even more remarkable, these terms are actually used by regular people, and most Icelanders are appreciative and proud of their very unique and independent language.”

That said, Crawford cautions, the supposed changelessness of the language based on the Vikings’ Old Norse can be overstated.

“Even if you print a medieval saga with Modern Icelandic spellings and read it with modern pronunciation – a common practice in Iceland – Old Norse comes across as a distinctly different language,” he says. “Today’s Icelanders live in the same world as we do, and their dynamic language reflects that. Icelandic may be medieval in structure, but it is modern in spirit.”

Crawford, a consultant on the film Frozen and author of The Poetic Edda: Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes (a translation of a collection of Old Norse poems), says learning Modern Icelandic can open the door to discovery of contemporary Icelandic poets and novelists, as well as the myths and sagas handed down in Old Norse. Plus, he says, Modern Icelandic speakers have a leg up in learning the basics of Norwegian, Swedish and Danish.

Listen to Professor Crawford welcome students in Icelandic.

Doomed?

As to the debate about whether Modern Icelandic may be dying as more Icelanders turn to English, Crawford is doubtful.

Iceland’s extreme geography that features glaciers like Eyjafjallajokull is intriguing. So is its language. (Photo by Wikimedia Commons.)

“I don’t think Icelandic is in any more imminent danger of dying out than any other official national language; the languages of communities that are not backed by official use in any country are another matter,” he says. “There is a danger of misinterpreting widespread bilingualism as resulting in the inevitable complete replacement of the smaller language by the more widespread, but this tends to happen only in certain limited circumstances.”

The Scandinavian department teaches other modern languages, including Swedish, Norwegian and Danish.

Icelandic may be medieval in structure, but it is modern in spirit.

– Jackson Crawford

The Old Norse reading and grammar course in which undergraduate and graduate students read the ancient sagas has been taught since as early as 1892. The Saga Club, founded in 1954 and the campus’s longest-standing reading group, meets once a month to translate passages of Old Norse literature, as the language itself is no longer spoken.

Global perspective

IES has applied grants toward other less-than-common languages, such as Catalan, Irish Gaelic, Yiddish, Welsh, Turkish, Modern Greek and Norwegian. It also is using Title VI funds for expanding U.S. college and university infrastructure for teaching foreign languages and international studies this year to support a course on Kurdish language, culture and politics.

In addition to Modern Icelandic, the Berkeley Language Center reports a revival this year of the teaching of Khalkha Mongolian, the standard language of the country that stretches from the Gobi Desert to Siberia.

The two new classes bring to 59 the number of foreign languages taught at Berkeley, according to Richard Kern, director of the UC Berkeley Language Center and a professor of French. That compares to 41 at UCLA and 70 at UC San Diego. As far 2012-2013 bachelor’s degree recipients who entered Berkeley as freshmen, 2,469 (48 percent) took one or more foreign language courses at Berkeley before completing their degree.

“With globalization, we’re encountering people with other languages and cultures all the time, and seeing that the world, and even an academic discipline, looks different when we step out of an English-language perspective,” says Kern. “I think students find that intrinsically interesting and want to learn more.”

RELATED INFORMATION

- Listen to a few basic Icelandic greetings or read an Icelandic Language Blog