Early Journalism School professor James Spaulding dies at 94

James Spaulding was one of the first professors recruited to teach at UC Berkeley's Journalism School.

August 17, 2015

James Spaulding, professor emeritus at the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and one of the first instructors to teach at the J-School, passed away on July 30 at his home in Calistoga, Calif., at the age of 94. His colleagues and students remember him as a tough but beloved teacher with encyclopedic knowledge of medicine, a keen sense of language, and a nose for good wine.

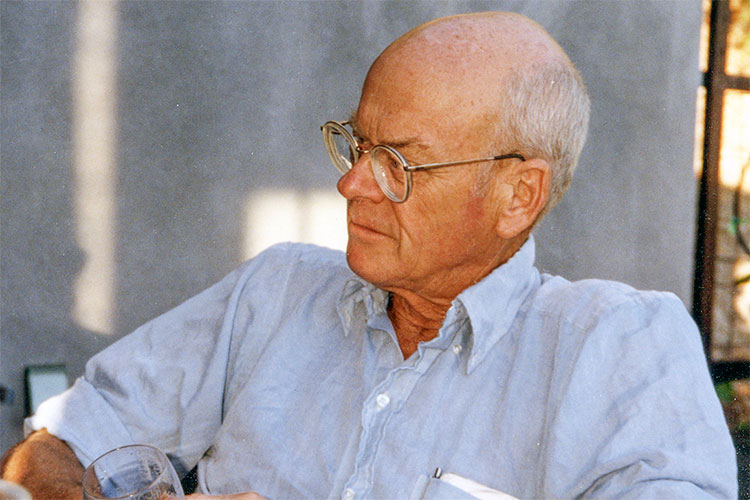

James Spaulding was among the first professors recruited to teach at the Graduate School of Journalism. (Photo courtesy of Martha Casselman.)

Spaulding was recruited to teach at the Journalism School in 1969 by its founding dean, Edwin Bayley, after a 28-year career as a science and medicine writer for the Milwaukee Journal, where the two had been colleagues. He was known for the column, “Report on Your Health,” and served as president of the National Association of Science Writers in 1968 and 1969.

“He was a superb and tough teacher,” said Andrew Stern, another professor emeritus who joined the school at the same time as Spaulding, “Jim knew so much about medicine you could ask him any question about any disease and he had the answer on his finger tips. His students adored him.”

Spaulding, who was born in 1921 and grew up in Des Moines, Iowa, was not only a journalist and teacher, but a father, an athlete – he ran, hiked, biked and played tennis throughout his life – a veteran of the Army Air Corps, and a vintner. In 1971 he moved to California with his first wife, Barbara, to take a senior lecturer position at the J-School. A year later they founded Stonegate Winery in Calistoga. It was among the first wineries to spring up in the early days of California’s wine renaissance.

At the J-School, Spaulding taught courses in science and medical reporting, developing a reputation as an exacting editor and an excellent teacher.

“With sleeves rolled up, peering down through steel rimmed glasses, he slashed through their copy, missing no infelicities,” said Tom Leonard, university librarian and soon-to-be professor emeritus at the J-School. “’Infelicity’” he would strike. ‘Do you know if it is wire rim?’ he would ask. ‘Peer’ might get by. Probably not.”

Michael Castleman, who had Spaulding as a teacher and as thesis advisor, recalled, “I groused about all the red ink all over my work, but the rewrites he demanded taught me a great deal.” Castleman went on to become a best-selling book author writing on health and medicine.

“Jim was the professor you dreamed of having in J-School,” said former student Rick Weiss, ”hard-nosed and old-school but at the same time a lover of language, a slayer of cliches, and a strict advocate for clarity and explanatory precision.” Weiss’s science writing career has included 15 years at the Washington Post and five years in the Obama White House.

“Jim was the quintessential ‘old school’ no-nonsense journalist and teacher,” said Tom Goldstein, professor and dean emeritus who met Spaulding in 1984. “He lived and breathed austerity, clarity and directness. For these virtues, he won a legion of fans among students and teachers.”

Spaulding’s work played an important role in shaping the J-School from its early days. As Leonard recalled, “Jim was more than a fearsome editor; he was an apostle of science writing who played no favorites, and was graceful and useful. The J-School got off to a quick and aerobic start under Jim.”

Spaulding retired from teaching in 1986, and met his wife of 28 years, Martha, a few months later at a wine tasting in San Francisco. He continued to run Stonegate Winery, and would often invite former colleagues Stern and Bayley for an afternoon of wine drinking and horseshoes in Calistoga.

He shared his passion for wine with his students, as well. “It didn’t hurt that he also would periodically invite us for tastings at his winery,” Weiss recalled. “I am so grateful for all he taught me – about reporting, about storytelling, and about vino verde noses I’d never considered, including grassy, weedy and the one I remember him reveling in most: ‘dirty socks.'”

Spaulding is survived by his wife, Martha, his sister, Jane Nordberg, three children and two grandchildren, as well as two stepsons and two step-grandchildren.