Whiskers and locks: reading U.S. history through hair

From bearded lady acts to the Victorian practice of hair collecting, grad student Sarah Gold McBride is teasing out the meaning of hair in 19th-century America, and how it reveals evolving ideas about race and gender.

November 10, 2015

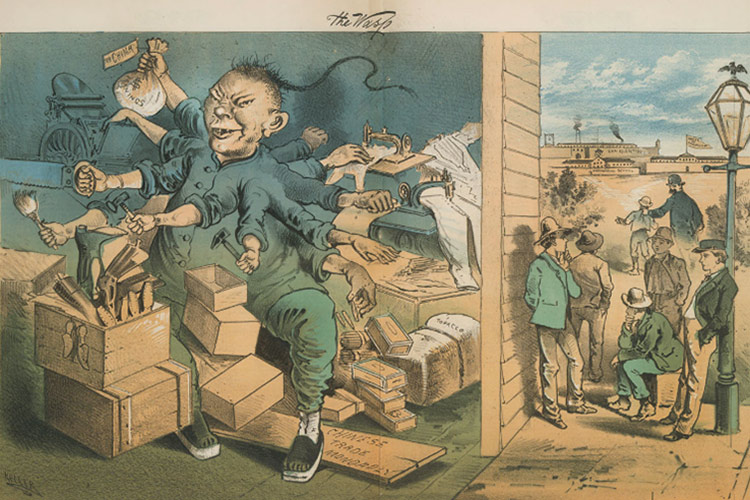

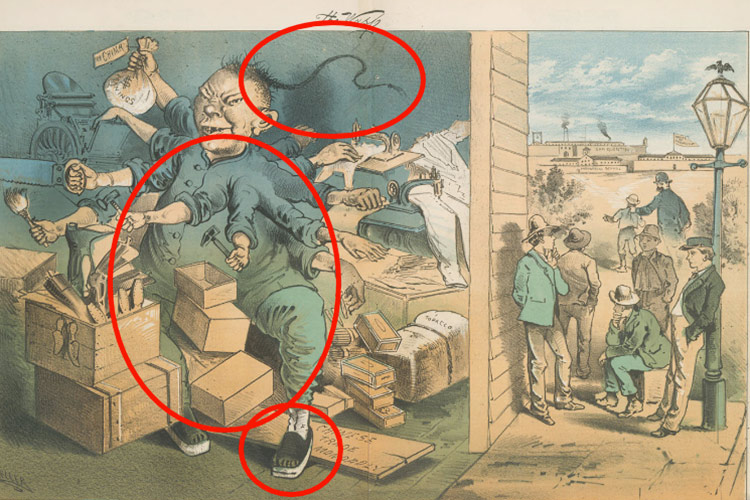

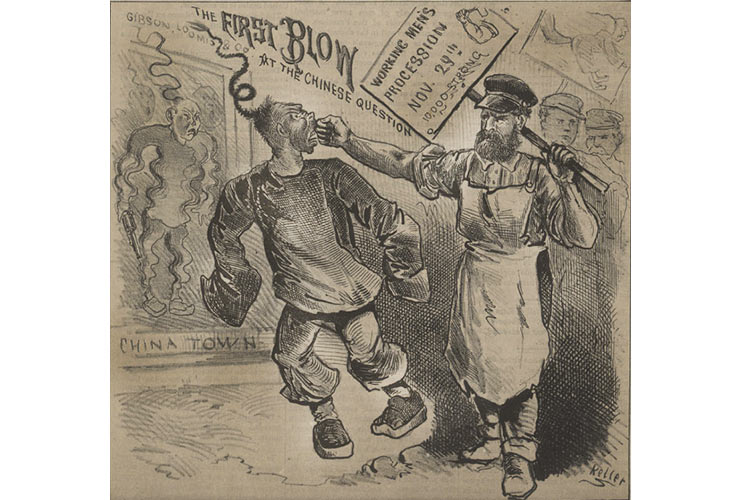

Sarah Gold McBride never set out to write about hair. It’s a research topic that has, well, grown during her extended academic career at Berkeley — offering a window onto the history of popular culture and Americans’ evolving ideas about race and gender. (Story continues below slideshow.)

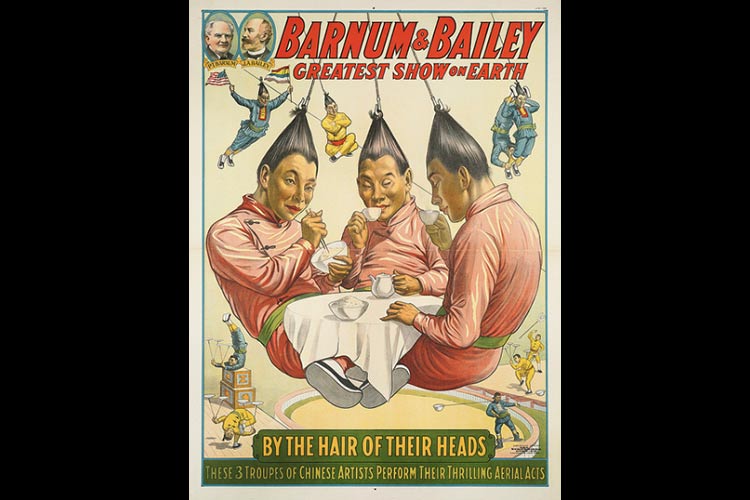

First there was her senior thesis on a pair of female conjoined twins, born in slavery, who were exhibited on the freak show circuit, both as young girls and, after emancipation, as adults. (As child performers, their proprietor pocketed the profits.) Next she studied freak shows themselves, which were hugely popular in the 1800s. That led to research on ”bearded lady” acts and the lives of the women they featured.

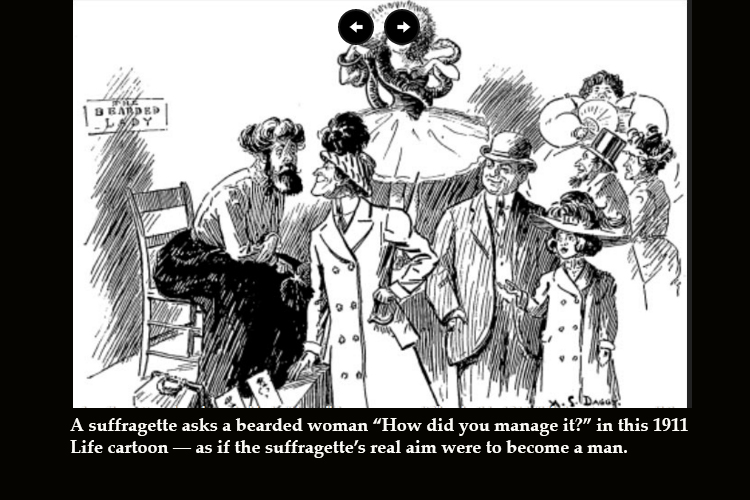

Now, as a Ph.D. candidate, Gold McBride is teasing out out the larger meaning of hair in 19th-century America. One chapter of her dissertation looks at the popularity of hair collecting in the Victorian era; another explores cultural understandings of male and female facial hair, and how the latter was used to critique early women’s rights advocates. She writes about the uses of hair in criminology, debates about long hair on men (and what it meant about masculinity and race) and more.

Gold McBride says that in 19th-century America, hair was believed to reveal not only a person’s race and gender but his or her true identity and character — qualities like trustworthiness, courage or criminality.

“Is hair any index of temperament?” one reader asked the Herald of Health, a New York health-science magazine, in a published exchange she cites. The editor responded in the affirmative, quoting at length from a recent treatise on human hair: “Fine, dark-brown hair signifies the combination of exquisite sensibilities with great strength of character…. [while] … harsh, upright hair is the sign of a reticent and sour spirit.” The list went on.

By the 20th century, hair became “a means of creative self-expression, or a way to signal one’s political or cultural affiliation,” says Gold McBride. “But what makes the 19th century different is the belief that hair could tell its own story” about a person, regardless of how that individual chose to wear their hair.

Why was hair accorded such authority at the time? Gold McBride argues that in an increasingly modern society (but before the Internet, credit reports or easily accessible public records), people looking for trustworthy means to size up strangers put stock in physical characteristics like skull measurements (popularized via phrenology), facial features (physiognomy) and hair. (The latter did not have its own pseudoscience, though in 1846 a New Orleans reporter proposed, possibly in jest, a new field of study to be called “whiskerology.”)

“Various amateur scientists, in the first half of the century, researched hair on a strand-by-strand level,” she says. They looked for instance, at hair-follicle shape for evidence that “black people and white people came from two separate origins.”

In pursuing her research, Gold McBride has mined libraries and archives and pored through newspapers, books, pamphlets and illustrations. And though traditional archives don’t offer the search term “hair,” digitization has changed the game for historians, notes Gold McBride.

“Google Books has been great for 19th-century history; you can search down to the text of the book,” she says. “Twenty years ago, that would have been impossible.”

Gold McBride caught the history bug her freshman year at Berkeley, when she happened to take a survey course on early U.S. history taught by Robin Einhorn. The professor emphasized “causes, effects and changes, not memorization” in passionately delivered lectures, Gold McBride recalls. “It just captivated me — and 600 to 700 of us in Wheeler Auditorium.”

“I’d always enjoyed writing,” she says, “and knew I had a knack for teaching,” having tutored in high school. “I sat in History 7A and saw the model of a job that involved both.” Becoming a history professor “is still, to this day, what I’m working toward.”