With rise of leukemia in children, $6 million grant funds search for causes

A UC Berkeley researcher leads a team of scientists discovering environmental exposures linked to childhood leukemia, which is increasing, especially in Latinos

July 26, 2016

A UC Berkeley-led research team will search for causes of leukemia — the most common cancer in children — with a new, four-year, $6 million grant from the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The award marks the second round of funding for the Berkeley-based Center for Integrative Research on Childhood Leukemia and the Environment (CIRCLE), directed by Catherine Metayer, a professor of epidemiology with UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health.

The new grant is one of five announced today by the EPA for research centers focused on children’s environmental health, and CIRCLE is the only leukemia research center funded jointly by the agencies.

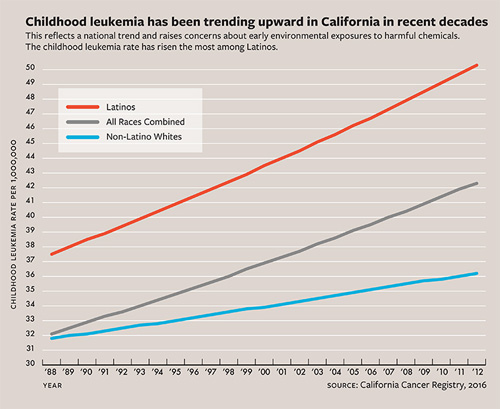

The incidence of childhood leukemia in the U.S. has increased by roughly 35 percent since 1975, according to Metayer, citing cancer statistics from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, and leukemia is one of the leading causes of childhood death in developed countries.

With availability of more effective treatments, survival has increased dramatically. Survivors, however, face many difficulties later in life, including debilitating medical and psychosocial complications, which also cause economic hardships for their families.

“Our goal is to identify the causes of childhood leukemia and to support prevention efforts by educating health practitioners, families and public health organizations on risk factors for leukemia,” Metayer said.

Focus on acute lymphoblastic leukemia

The grant will allow the scientists to build upon recent success linking the risk of getting childhood leukemia to specific environmental exposures. They will focus their investigations on California’s ethnically diverse population, and on a type of leukemia called acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). ALL accounts for four out of five cases of childhood leukemia.

CIRCLE scientists recently showed that Latino families are at greater risk for bearing children who develop ALL, and they will try to discover why this is true. “The rise in leukemia cases over a relatively short time frame points to a role for environmental triggers,” Metayer said.

CIRCLE scientists recently showed that Latino families are at greater risk for bearing children who develop ALL, and they will try to discover why this is true. “The rise in leukemia cases over a relatively short time frame points to a role for environmental triggers,” Metayer said.

Studies indicate that ALL in children often begins before birth, in the mother’s womb, and that exposure of the fetus to cancer-causing chemicals might play a role in initiating the disease.

CIRCLE researchers have refined laboratory techniques that more sensitively detect and quantify chemical exposures in biological samples from newborns and their mothers.

They also have pioneered analysis of house dust as an estimate of exposure to chemicals before and after birth, and found that dust levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are associated with increased risk of childhood ALL.

PCBs are industrial chemicals previously implicated in other cancers. Their production has long been prohibited by law in the United States, but PCBs persist in the environment. PAHs are released by the burning of organic substances, ranging from gasoline to meat. PBDEs are flame retardants used in furniture, plastics and foam products.

Metayer, who is chair of the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium, also notes, “Researchers in many countries found that exposures to solvents, traffic, pesticides and tobacco smoke are associated with the risk of developing childhood leukemia, while folate supplementation by the mother before or during pregnancy appears to have a protective effect.”

With the new funding, CIRCLE researchers will expand the scope of their research, and investigate ways in which chemical and nutrient exposures interact with genes and the immune system to influence leukemia risk.

“We will be conducting the first study to characterize a broad range of chemical exposures to the fetus, the first biomarker study to examine the impact of chemical exposures on the maternal immune status during pregnancy and its relationship to childhood ALL risk, and the first study to test suspected chemical triggers of leukemia in a mouse model of childhood ALL,” Metayer said.

Metayer and colleagues have led leukemia research collaborations since 1995, predating the first CIRCLE award in 2009. They have worked with clinicians and families to build the California Childhood Leukemia Study with the most comprehensive exposure data and biospecimen archives worldwide, and recently, they have used cancer registries and birth records to identify every childhood leukemia case in California since 1988. In addition to UC Berkeley scientists, CIRCLE collaborators include scientists from UC San Francisco, Yale and Stanford universities.

Measuring chemical exposures in newborns

With the new award, CIRCLE researchers will conduct three major projects. The scientists will be analyzing archived blood specimens from pregnant women and neonatal blood spots from the California Department of Public Health to measure in utero chemical exposures, to profile aspects of the immune system and to identify genetic alterations that lead to leukemia. They also will be testing chemicals in mice and launching new education and outreach efforts related to leukemia prevention.

In the first project, co-led by Metayer and cancer epidemiologist Xiaomei Ma at Yale, the researchers will explore how the status of the maternal or neonatal immune system is affected by chemical exposures in the womb.

CIRCLE scientists and other researchers in recent years have found intriguing associations between the immune system and the development of childhood leukemia. For instance, children who develop ALL tend to have more severe infections during the first year of life, and their mothers also are more likely to have experienced infections while pregnant, Metayer said. In addition, levels of specific immune system signaling molecules may be altered. As part of this first project, scientists will measure levels of signaling molecules called cytokines, which are produced primarily by immune cells and help guide immune responses.

The second project will be led by UC Berkeley’s Stephen Rappaport, an expert in research on the “exposome,” which refers to the totality of exposures to an individual from within and from the outside environment over the course of a lifetime. Rappaport optimizes lab protocols for using a technique called mass spectrometry to quantify thousands of chemicals found in blood samples, analogous to the way geneticists now can scan the entire genome for mutations. The CIRCLE team may identify new associations between prenatal chemical exposures and childhood leukemia using these refined methods.

The third project, led by CIRCLE co-director Joseph Wiemels, an associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at UC San Francisco, focuses on the role of genetic variations that may confer leukemia susceptibility, as well as on “epigenetic” modifications, a type of chemical change in DNA that may be influenced by chemical exposures. These modifications may occur before or after birth, can be long lasting and influence the functioning of genes.

The new award also funds a Community Outreach and Research Translation Core led by Mark Miller of the Western States Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Unit at UC San Francisco, with the aim of improving environmental health literacy in various audiences, including health care providers and Latinos, and providing a scientific basis for developing prevention programs for ALL in children.

“The history of environmental health is rife with examples of lessons learned late — chemicals with early warning signs of health impacts that took many years or even decades to conclusively prove were hazards,” Miller said. In the meantime their use continued and they accumulated in the environment. Well-known examples include PCBs, DDT, lead and tobacco smoke.

“We have enough information now,” Metayer said, “to begin to explore ways in which to reduce children’s exposures that have been consistently linked to increased risk for childhood leukemia, and we will continue to search for new risk factors to better guide future programs for prevention.”

RELATED INFORMATION